The Sunday morning after America's independence day, we grouped into cars to roll downslope to the coastal capital city of Liberia. Monrovia it's called - named after James Monroe, the founding father figure, 5th president of the United States, William & Mary alum, and advocate for the American Colonization Society in Africa who ironically died on July 4th, 1831 - five years to the day after the second and third presidents, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, died.

The short-distance trip was impeded minimally by traffic and one county-border guard bribing, as most funny-business prefers the less holy days of the week. In the city of one million, our car fringed the main Peace Corps office until we caught a glimpse of the circular logo and debouched. We were to spend two nights in “town” (n. – the city of Monrovia) and get a lay for the land. By touring around the city, searching for places to eat, and talking with other foreign-aid workers, we gained worthwhile insights.

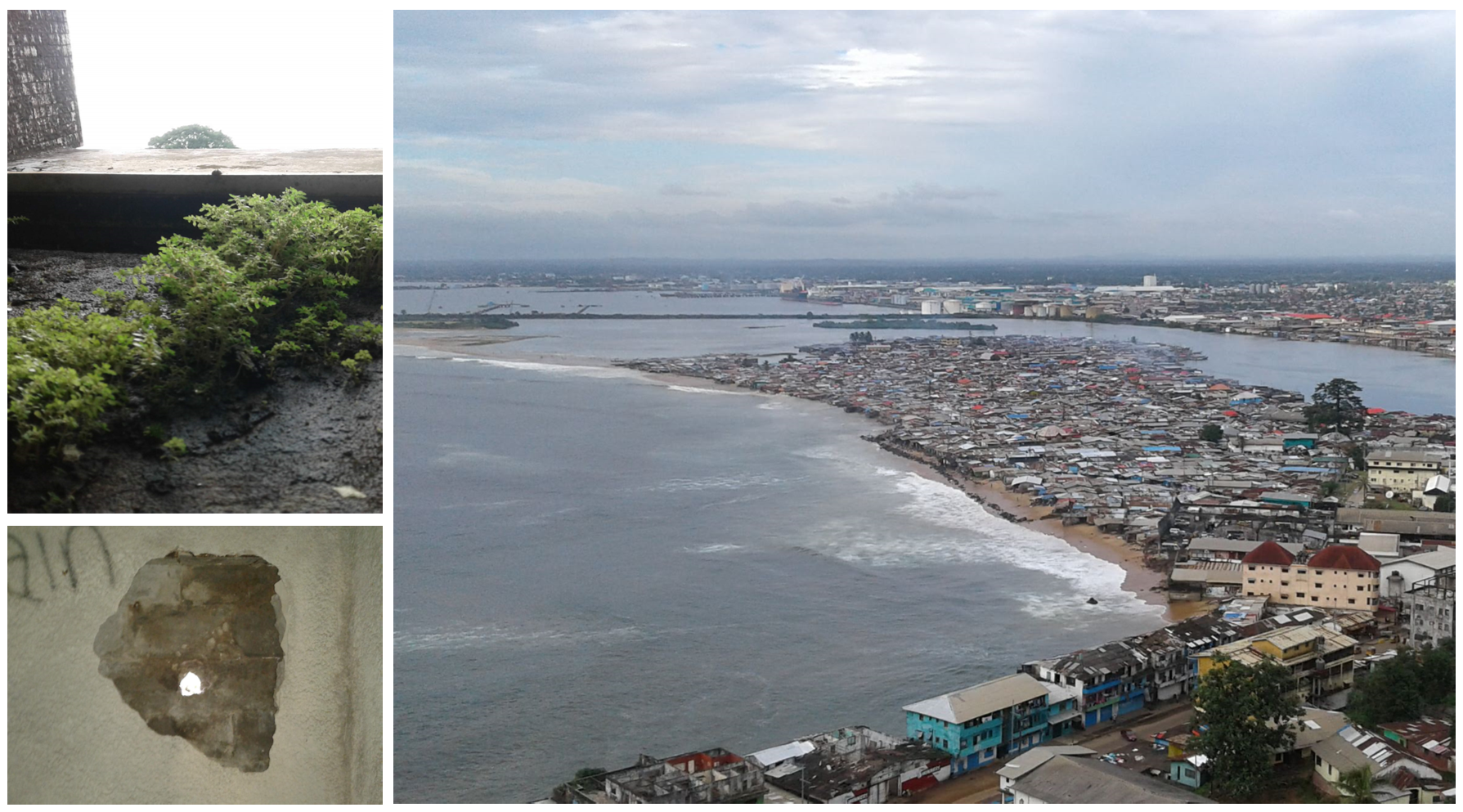

The hotels, variety of cuisines, and paved roads implied the more developed side of Liberia. Lebanese business-people own much of the housing infrastructure in the city proper and charge a premium for western amenities. Prices of goods are similar to cities in the United States, however, services like transportation reflect the lower cost of labor. Traffic is dense with motorbikes and Kay-Kays (n. – 3-wheeled, door-less taxis resembling Southeast Asian Tuk-Tuks) sifting through the honking 4-wheelers. Ice-cream consumption – which is a pipe-dream for Peace Corps Volunteers outside of town – is rampant. Beaches skirt the western limits of the city, but the waters that shape them are rich with sewage and impose a rip-tide that would frighten even surfer-dudes off the coast of Australia. Some structures still bear scars from the civil war some 20 years ago, most powerfully The Ducor. What was once the largest upscale hotel in West Africa remains only in its fractured skeletal form. The central staircase is crumbling, exposing rusty tendons of rebar. Moss and mold rent cavities on every floor. Fenestral openings hold no glass, and small pores for gun barrels permeate light inside. The scalp of the building is the highest point for miles and overlooks the Atlantic Ocean and West Point, the densest slum of Liberia.

Clockwise from top left: Positive phototropism shown as small plants on the 5th-floor face towards the main light source; View of West Point, a densely populated slum formed atop dredged sand, where an estimated 75,000 Liberians live; a port used for outward gunfire along a set of stairs.

While in Monrovia, my group took the chance to observe a critical-thinking workshop led by two volunteers at the Armed Forces of Liberia base. The half-day program encouraged these middle-aged military men (and one woman) to use reason and consideration to achieve positive outcomes for all. One activity had groups designing and constructing boats from tin-foil with the goal of floating and toting the largest cargo of bottle caps.

A discussion on sex and gender taught the distinctions between the biological male and female and the societal man and woman. The soldiers were asked to answer what makes men and women. Their responses were familiar to me but more extreme, or, by western standards, outdated. Men are expected to be forceful and the financial provider for the family – those who can't provide are weak and shameful. Polygamy is common and some men can marry upwards of 10 wives. Men make the main decisions for their homes. Women should stay home to keep the house immaculate and discipline the children who misbehave. Their education is not essential.

Afterward, the volunteers introduced the ideas of equality and equity; the former meaning to be fair and the latter meaning to provide a boost for those who need it (assuming different starting points).

Getting our bearings oiled for solo visits to Monrovia was a lovely way to spend 3 days.

The Commonwealth of Liberia celebrates its own independence on July 26th; Hence the playful remark “my 26th on you” (statement-question – you will buy me a gift for the independence holiday). The most effective retort is to restate the phrase and share a laugh. I celebrated the momentous day in Liberian fashion – playing a football match in the morning against our Liberian Peace Corps staff and cooking plenty (adj. – lots of; very much) dishes. Our American team tied the match 2-2 with a header from John “Castration Station” Castro in the final seconds, thus a rematch is in the works. To refuel I shared some American cuisine with my family in the form of flatbread (pancakes) to pair with fried cabbage and rice. Music was blaring from houses, keeping a vibrant party on every dirt road.

Liberia was the first African country (1847) to claim Independence from its colonial grasp. Power was in the hands of the Americo-Liberians, the freed slaves from the United States who hoped to modernize and Christianize the indigenous tribes that called the fertile “Pepper coast” home. In doing so, their simultaneously adopted Constitution was modeled after what they knew best – the US system. They incorporated checks and balances through three primary governmental branches; executive, legislative, and judicial. However, instead of the US Republican vs Democrat, Liberia has developed a barrage of political parties that all claim to lift the country out of poverty and corruption. Parallels between the two countries can be found at every turn: The Liberian flag is identical to the US flag but with one central star in the blue section; Devotion at school starts with “I pledge allegiance to the flag of Liberia, for which it stands...” One of the counties is named Maryland. Every Liberian dreams of coming to America and many will ask me to “carry” (v. - to escort or lead the way) them there. Some even refer to it as “Small Heaven.” Liberia is believed to be the 52nd state, and Liberians see Americans as brothers of the same blood. I often find myself dispelling Utopian myths of my home country by helping Liberians understand that nowhere is perfect.

If only I had a chance to spread the word as I did for Peace Corps summer school: through the airways of Radio Atlantic in Margibi County. Radio is the medium of news here, and the host of an evening show let us promote our school through the broadly-casted station. The next Monday, some 900 students came.

Model school – the 7th - 12th grade summer school taught entirely by the lot of us teachers-in-training – began the third week in July. It was our chance to engage with students in the Liberian classroom setting, become frustrated, adapt, and try again. My cluster of 5 taught 120 students between 2 rooms:7A & 7B. Notorious 7B. It was a smaller class, but ripe with trouble at every desk. A rowdy, bold, and tricky bunch they were. Over the first few days, I put up with a constant mumble-rumble, trying to speak and write over the noise for the half of the class that was attentive. I focused on sticking to the lesson plan, simplifying jargon, and “moving” forward. My rationale was simple: share the information I had with those who cared to listen.

After every day of school, we took half-an-hour to give and receive constructive criticism among the cluster and from Liberian teachers and seasoned volunteers. After one especially chaotic and exhausting day of teaching, a former volunteer gave the advice I needed. She looked at me and demanded, “Stand up and kick me out of your class.” And I did. But I smirked. And so I did it again, reminding myself that any hint of a smile would be perceived as weakness in the Liberian classroom. She then told me that I need to win back respect in the classroom – and the surest way to do so was through a strike of the teacher's hammer.

The next day, I kicked a student out within the opening minutes of my class. I had the rest of the students write what respect meant to them, quietly. I didn't shy away from punishing distracting behavior, regardless of how much it reminded me of a past me. Much like the Atkins diet, the results were astonishing. All eyes were on me, notes were being taken, and I could hear my voice resound off the walls. Looking back at it, this experience was the essence of model school – learning to manage and interact with the students.

Once I re-established authority and calm in the classroom I could move on with content. Earth Science. I taught the rudiments of weather, climate, and the three rock types (sedimentary, igneous, and metamorphic). I even stuck in a little environmental bit by including humans as one of the factors capable of influencing our climate. My students said “CO2” like conference-bound champions, but could have benefited from some pressure to work on “meh-ta-mor-fik”.

Watch a video of my daily walk to model school!

A good chunk of our students from 7A and 7B huddled together for this photo on the last day of classes.

My sister Matu graduated from St. Augustine's Episcopal High School this past Sunday. When youngsters graduate kindergarten in Liberia they dress in cap and gown and ride around the city laying on the horn – I'll let you imagine the upgrade for high school graduation. Relatives from town arrived the day before and began preparing food; 60 cups of rice, hundreds of onions, chicken legs, and over a thousand small peppays.

My ma recruited me to photograph the graduation ceremony using Matu's plus-one. As I entered the event hall with my admission ticket I was directed on stage for a chair, as seating was filling up quickly. Before too long the introductions began, and sure enough, I was front and one-right-of-center. Facing all the graduates and parents as if I had an ounce of qualification to be on stage next to the school principal and the County Education Officer, I nodded through lengthy speeches and sang the Liberian national anthem on queue.

Back home, children summoned by music playing on the loudspeakers since 8am were gyrating away. Some family members, I included, gave speeches for Matu as the Jolaf rice (n – fried rice seasoned with tomato paste and bouillon cubes) was doled out. Cane juice (n. - spirits derived from cane sugar) mixed with condensed milk equals Liberian egg nog – the specialty drink of the evening. Four other Peace Corps volunteers came for the festivities and to meet folks from my side of the coal-tar. Later in the night, the crew playing the music put on Mano (a Liberian tribe from the mountainous lands of present-day Nimba County) tunes per request of my grandma. Here music has a way of possessing dancers – almost as if a set of sonic strings tug limbs every which way. Grandma and I let loose and danced late into the night...

Clockwise from left: Sister Matu and family friends from town grooving for the camera; Peppay post mashing in the wooden mortar and pestle; Two of the fellow Peace Corps who joined for the festivities.

Ongoing Ventures:

My weekly girls club came to an end this past Saturday. Katie and I had a committed group of girls vote on their specific interests for the final three meetings. Sexual Reproductive Health won by a debris flow. It made sense, considering most of the girls are hitting puberty. We gave an anatomical overview of “receiving” (n. - menstruating), taught about STIs, and led the always entertaining condom demonstration. Lastly we helped them sew Reusable Menstrual Pads (RUMPS) from Lappa and plastic water bags. Receiving keeps girls away from school as the shame of potentially bleeding in public feels too great and few affordable options exist. Our club ended with a booming cheer and we said our so-longs.

For the past five Tuesday's the cohort has gathered after training or teaching to roast one another. The volunteer who delivers the best joke is afforded the gracious opportunity to be roasted the following week. One propitious jab won me the honor. I won't divulge any further details in writing but I truly enjoyed the experience – feel free to inquire.

The economic situation in Liberia has undergone notable stimulation. As inflation sped along, president George Weah announced

"An immediate infusion by the Central Bank of US$25 million into the economy to mop up the excess liquidity of Liberian dollars.”

The details of this proposal are scarce, and its unclear where the money is sourced from. A meeting with all the money-changers in Monrovia and the surrounding areas were called to town and told to keep the rate at 1USD=150LD. In two days the rate dropped from almost 170 to 110 – and has since remained fixed at 150LD. Fastening the exchange rate to the stable USD is a widely used macroeconomic tool, and for now some confidence has been restored.

So long Kakata...

In a week from now I will be in a new corner of this land - the Southeast. Find me in my Orange Kente Lappa shirt below. Garraway in Grand Kru County - a village of perhaps of 5000 people.

The map of Liberia with volunteers standing at our respective sites after removing our blindfolds.

It's rural; over 20 hours of good-condition driving from Monrovia. The site is new and many questions are still unanswered - but I am told I can see the Atlantic from home.

Here's to a new beginning!