100% of Steem Dollars from this post will be donated to Project Curie. You can read more about Project Curie here.

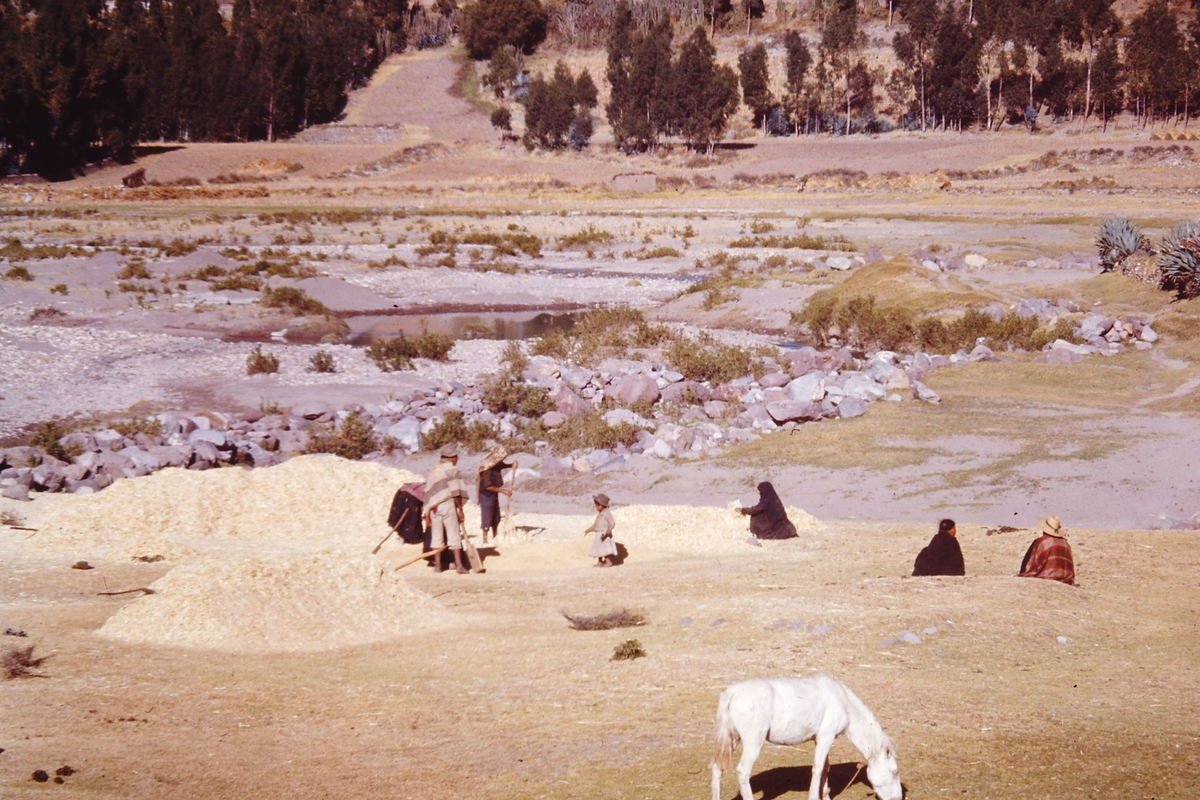

All photos were taken by my father, Bill Baumeister, in his 1970's Latin America backpacking journey.

Introduction

“From the South, House of the Eternal Sun, may right action reap the harvest so we may enjoy the fruits of planetary being”.

This quote is part of the Mayan Prayer to the Seven Directions, and is used in ritual practices. It shows the strong connection between the elements, agricultural practices, and Mayan worldview.

Pre-Columbian Mayan and Incan worldview is based on their observations of the natural elements, and this worldview in turn has informed their agricultural practices.

This post will examine which natural elements created the pre-Columbian worldview, and define what this worldview is. It will then to find the main pre-columbian worldview principles of reciprocity, complimentarity, duality, and cyclicity within pre-Columbian agricultural practices.

The Pre-Columbian Worldview

The Mayan worldview consists of its main principles of duality, complementarity, cyclicity, and reciprocity.

Duality is “not a belief in binary oppositions, but rather a belief in eschatology, cyclical reptitions, and complementarity” (Figueroa, 2004: 7).

Duality is the core of pre-Columbian worldviews and this concept informs all of the other main principles. The Mayan worldview states that the universe and the self is dual in nature. Every human has a physical side as well as a supernatural side (Figueroa, 2004: 1).

Most closely related to duality is the concept of complementarity, which “involves the interrelation of the different parts of the universe whereby one thing supplements another” (Figueroa, 2004: 7).

Examples of complementarity include light and dark and man and woman.

Cyclicity, on the other hand, informs the pre-Columbian understanding of time and “implies a recurrence of historical events, meaning that every decision, act, and event is a consequence of an antecedent state of affairs” (Figueroa, 2004: 7).

For example, in Mayan mythology the Popol Vuh states that we are in the 4th world and that those before us were destroyed, and that this current world will be destroyed in a flood. This creation story stems from the concept of cyclicity (Figueroa, 2004: 4).

Lastly, the concept of reciprocity “involves a cooperative exchange between the natural and supernatural world, whereby gods and deities provide humans with order, continuity, life, and health and in turn humans give forth sacrifice, offerings, admiration, and loyalty through rituals and obedience” (Figueroa, 2004: 7).

This concept is seen most clearly in pre-Columbian agricultural practices, where rituals are used to provide the deities with an offering in return for a good harvest. These pre-Columbian concepts are informed by and reinforced by the natural world.

The Sun and Moon

The two most important universal beings that have created the pre-Columbian worldview are the Sun and the Moon. They are two of the main formations of the Mayan worldview because of their role in Mayan agriculture (Figueroa, 2004: 1).

Figueroa explains that, “The sun’s movement across the sky was and still is the basis for both natural and supernatural explanations of the origins of the cosmos, which have given rise to calendrical, agricultural, and cosmic systems” (Figueroa, 2004: 1).

The Mayans believe in deities, which are gods and goddesses that each watch over parts of the universe and who are dual in nature. Each deity has two to four identities that are dependent on and together create the deity. Such complementary identities differ in age, gender, ect, and an example is the Sun God and Moon Gooddess or the man and woman primordial pair (Figueroa, 2004: 2).

The Sun God, which is “not only…the foremost ruler of time and space, but its movement is the basis for the Maya agricultural calendar…and is essential for the maintenance of life, order, and cyclicity”, is the male energy (Figueroa, 2004: 2). The Moon Goddess, which is complimentary to the Sun God, is the female energy. It is through the duality of the Sun and Moon that the Mayans worldview is centered around the concept of complementarity.

Both the Sun God and Moon Goddess are revered for their cyclical movement that creates the Mayan’s concept of time (Figueroa, 2004: 2). The Sun and Moon were also tracked to determine the two solstices and two zenith passages. These events were all used as markers for when to start planting and harvesting. These events also marked passages of both 365 days and 260 days. The 365 day cycle marked a Vague Year while the 260 day Sacred Almanac was used to create the 52 year Calendar Round (Zaro and Lohse, 2005: 86). The moon’s cyclical movement of 260 days dictates the time of sowing, planting, and harvesting corn, which is the same amount of time it takes to create a human (Figueroa, 2004: 2). The Mayan’s agricultural practices are cyclical, as each year crops are planted and harvested at the same time in correlation to the sun and moon cycle. The solar and lunar cycles give rise to the cycle of human reproduction and seasonal agriculture, which has in turn given rise to pre-Columbian worldviews.

Other Universal Elements

There are other universal elements that have informed the pre-Columbian worldview, among them the cardinal directions. The Mayans believe that the universe is made up of a celestial heaven, earth, and the Underworld, and that there are 5 cardinal directions – north, south, east, and west, and the center (Figueroa, 2004: 1). Many Mayan communities have designated colors to each of the directions. For example, one community has designated north with white and maize, south with red and wind, east with white and rain, and west with black and death (Zaro and Lohse, 2005: 84). This exemplifies how agricultural ideas such as fertility, famine, and maize are all vitally woven into the Mayan’s cosmo structure (Zaro and Lohse, 2005: 85). East and west signify the sun and moon passage such as the solstices while north and south signify the elements of opposition such as the heavens and underworld (Zaro and Lohse, 2005: 88).

As Zaro and Lohse explain, “the elaborate prehispanic integration of cardinality, opposition, seasonality, the passage of time, and the movements of celestial bodies provided powerful instruments for conveying notions of wholeness, completion, the cyclical nature of time and creation, and of fertility and renewal, all significant themes that pervaded more than strictly agricultural or stricly ritual aspects of daily Maya life” (Zaro and Lohse, 2005: 89).

Universal elements are observed, and through these observations the Mayans created a worldview that has been integrated into their agricultural practices. The Mayan worldview is also largely based in its geography and weather. Ceiba trees were seen as the center of the cosmos while the seas were the entrance to the underworld (Foster, 2002: 91).

Additionally, the Mayans experienced a rainy season and dry season, each lasting for about half of the year. For half of the year everything resembled death and for the other half the world came alive again, which informed their worldview of duality.

Foster explains that, “these perpetual cycles contributed to the Maya beliefs that death leads to rebirth and that renewal follows sacrifice” (Foster, 2002: 92).

Once again, it is clear that the Mayan worldview did not randomly come into existence, but rather was created from their strong observations and connections with the natural world around them.

Agriculture and Worldview

The worldview of the Mayans and Incans can be found within their agricultural practices. Hastorf argues that agricultural systems are a mirror of the political and social situation at the time.

He continues to say that “agricultural systems are more than a place for food production, therefore; they are monuments to the regime’s ideological worldview and systems of control” (Hastorf, 2009: 53).

Policies and beliefs of a certain era can be found in the terraced fields to the canals to the sunken gardens. Agricultural systems do not only control the food supply of a civilization but also act as an agent of cultural and social organization (Hastorf, 2009: 53). For example, if an agricultural system is a top-down system implemented by the political regime, it may act as an enforcement of the regime’s desired worldview for its populous.

This is because “farmers continually work among their agricultural fields and irrigation systems, day in and day out. Such landscapes form the people that live in them” (Hastorf, 2009: 53).

Further, it is easy to find a reflection of an era’s political power in its old monuments and civic buildings. While it may not be as apparent, such a reflection can also be found in an ancient civilization’s irrigation canals and terraces (Hastorf, 2009: 54).

Hastorf argues that “political order that is implanted in built centers is itself also reflected in rural territory, creating a dynamic vision of the universal order in both locales, reflecting back on each side of the built world” (Hastorf, 2009: 55).

Agricultural technologies are formed from a civilization’s worldview, and on the other hand ideologies are created and reinforced by such agricultural technologies. Behind the functionality of a field and of a hoe lie a civilization’s worldview imposed in its environment. The Incan civilization contained the idea of “craft”, which is the idea that things are created to be both functional and beautiful, and therefore have hidden cultural meanings behind how they were crafted (Hastorf, 2009: 56). The Incas worshiped Pachamama, mother earth, for giving them all of their resources. They also worshiped spirits of mountain peaks, outcrops, and springs for providing productivity (wak’a). This worshiping is found in carved rocks and beautifully planned out waterways (Hastorf, 2009: 57).

Canals were made to mark family territories, therefore kinship and community lines are also found in the Inca’s irrigation systems. It is apparent that agriculture and culture and interwoven, and that one informs the other.

Incan Rituals

Incan agricultural rituals are an example of reciprocity, complementarity, and cyclicity. Agricultural work and rituals are two complimentary halves to the Incan agricultural tradition.

Doutriaux explains that “Andean rituals are perceived not only as an aid to agricultural production but as an integral and indispensable part of the agricultural cycle itself.” (Doutriaux, 2001: 93).

Agriculture and its complimentary practices were central to the worldview of Incan life (Doutriaux, 2001: 94). For the ritual of the sowing of maize, fasting was practiced as a form of reciprocity (Doutriaux, 2001: 95). Agricultural rituals join together the physical world with the supernatural world by offering sacrifices to deities in return for good harvests, reflecting the principle of reciprocity.

Additionally, “rituals are a form of repetition, a re-enactment of what was done in the past, an imitation of previous rituals. As such, they imply a certain continuity with the past.” (Doutriaux, 2001: 96).

This stems from the belief of cyclicity. In this sense, rituals are a method of inserting Incan’s cyclical concept of time into their everyday farming life.

Lastly, ritual action based in agriculture was also a means for the Incan empire to assert and reinforce their worldview (Doutriaux, 2001: 106).

Mayan Rituals

The Mayans practiced agriculture rituals in a very similar manner to the Incans. Precolumbian Mesoamerican civilizations contained vast agricultural knowledge, such as soil types and growing cycles. Complimentary to this technical agricultural knowledge, these civilizations practiced agricultural rituals that were deeply embedded into their yearly cycle (Zaro and Lohse, 2005: 81).

Zaro and Lohse state that, “the attendant rituals that were deeply embedded in a worldview focused to a very large degree on the cosmos, marking the cyclical passage of time, and defining the role of living people in relations to the supernatural” (Zaro and Lohse, 2005: 81).

Many rituals included sacrifices and related to fertility or water. They also tracked seasonal changes for growing periods by movements of celestial bodies (Zaro and Lohse, 2005: 81). The Mayan farmers created rituals to coincide with annual cycles of agriculture.

This honoring of the cycles allowed Mayan farmers to “engage in food production within the framework of a worldview shared by other members of society, a worldview that focused at once on the heavens and earth and all that surrounds them” (Zaro and Lohse, 2005: 96).

Corn Deities and Complementarity

Corn was the most important crop for the Mayans and the principle of complementarity can be found within their corn practices.

The Mayan’s worldview was partially based on complementary pairing such as male/female (Bassie-Sweet, 1999: 2). Such complementary pairing can be found in corn production.

In Mayan tradition, the man plants and harvests the corn while the wife processes it into food (Bassie-Sweet, 1999: 2). These agricultural activities are complementary and require both opposites of the whole.

Further, the corn plant contains both male and female parts: “The male tassel produces pollen, which falls on the silk of the female ear and fertilizes it. A mature corn plant is incomplete without its female ear of corn, just as a man is incomplete without his wife. The mature corn plant is the epitome of the complementary male/female principle” (Bassie-Sweet, 1999: 3).

The Mayan myth of human creation was that the gods made humans from a white corn seed (Bassie-Sweet, 1999: 2). With the belief that humans are created out of corn, which is half male and half female, humans must also in turn be half male and half female.

Conclusion

The Mayan and Incan worldview are created from the Sun and Moon, cardinal direction, geography, and weather. Just as modern civilizations look to science and natural phenomenon to explain the world, pre-Columbian civilizations also observed universal elements to provide an understanding of life. This understanding of life is reflected in a civilization’s agricultural system.

Tractors, synthetic fertilizers, and GMO crops are a reflection of a modern western worldview. Similarly, agricultural rituals, corn deities, and cyclical agricultural calendars are a reflection of a pre-Columbian worldview.

It is in studying ancient civilizations’ agricultural practices that modern day civilizations will be better able to understand the beliefs of their ancestors. To finish off with the Mayan Prayer to the Seven Directions that this post began with:

“From Above, House of Heaven, Where star people and Ancestors gather, May their blessings come to us Now; From Below, House of Earth, May the heartbeat of her crystal core, Bless us with harmonies to end all war; From the Center, Galactic Source, which is everywhere at once, may everything be known as the light of mutual love.”

Sources

Bassie- Sweet, Karen. 1999. Corn Deities and the Complementary Male/Female Principle. Presented at La Tercera Mesa Redonda de Palenque.

Doutriaux, Miriam. 2001. Power, Ideology and Ritual: The Practice of Agriculture in the Inca Empire. Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers. Vol. 85, pp. 91-108

Fischer, Edward. 2001. Logics and Global Economies: Maya Identity in Thought and Practice. University of Texas Press.

Figueroa, Alejandro. 2004. Mayan Concepts of Self: The Duality of Belonging.

Foster, Lynn. 2002. Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World. Oxford Press.

Hastorf, Christine. 2009. Agriculture as A Metaphor of the Andean State; in Polities and Power: Archaeological Perspectives on the Landscapes of Early States. University of Arizona Press.

Zaro, Gregory and Lohse, Jon. 2005. Agricultural Rhythms and Rituals: Ancient Maya Solar Observation in Hinterland Blue Creek, Northwestern Belize. Latin American Antiquity. Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 81-98