Greetings Steemers!

Every family has a skeleton in the closet. This is how I found mine.

First sentences are important: They are magnets for short attention spans. We will get to that skeleton shortly.

First of all, thanks for a great reception to my first post:

@neilstrauss/hate-mail-from-phil-collins

I’m excited by this community because, among other things, there’s the model, which is inclusive rather than exploitative of “content producers.” It’s amazing to watch the community evolve. And it’s mostly positive. That is, except for a few Your-Posts-Are-Making-More-SBD-And-I-Think-Mine-Are-Better-So-I’m-Going-To-Downvote-Yours haters.

(Not to mention the We-Want-More-People-Here-But-Only-If-They-Don’t-Write-Popular-Posts-That-Compete-With-Mine individuals – you know who you are.)

So this is my long-overdue IntroduceYourself post.

My name is Neil Strauss, and I’ve written eight New York Times best-selling books and thousands of articles for Rolling Stone and The New York Times. My life goal when I was eighteen was simply to write for the local weekly paper, so all this has been beyond a dream come true.

So this IntroduceYourself is about passion, purpose, and dreams.

I’m going to tell my story here, which is something I’ve never done before, not even on my own blog or in my books.

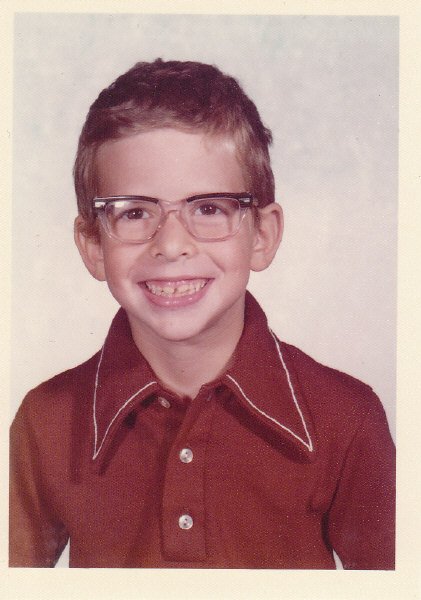

When I was a kid, I was the smallest kid in class, had thick glasses, wore cheap polyester clothes, and was always picked last for sports teams (or on a really exciting day second-to-last), even after all the girls in the class. My mother was constantly criticizing and punishing me, which didn’t help my self-esteem much either:

So I escaped into books. There, I found a world where kids like myself were stopping crime and saving the world (even when they were grounded) and breaking the rules and successfully dealing with problems like mine.

It opened my eyes to the power of words, and soon I was reading books way beyond my age level. I could usually be found walking around school with my head down, an open book in my hands. Even during naptime, I cradled a book between my folded arms and continued to read.

There was one other person in my class who read a lot named Alyssa—and I wanted to marry her, even though I was never able to work up the courage to talk to her.

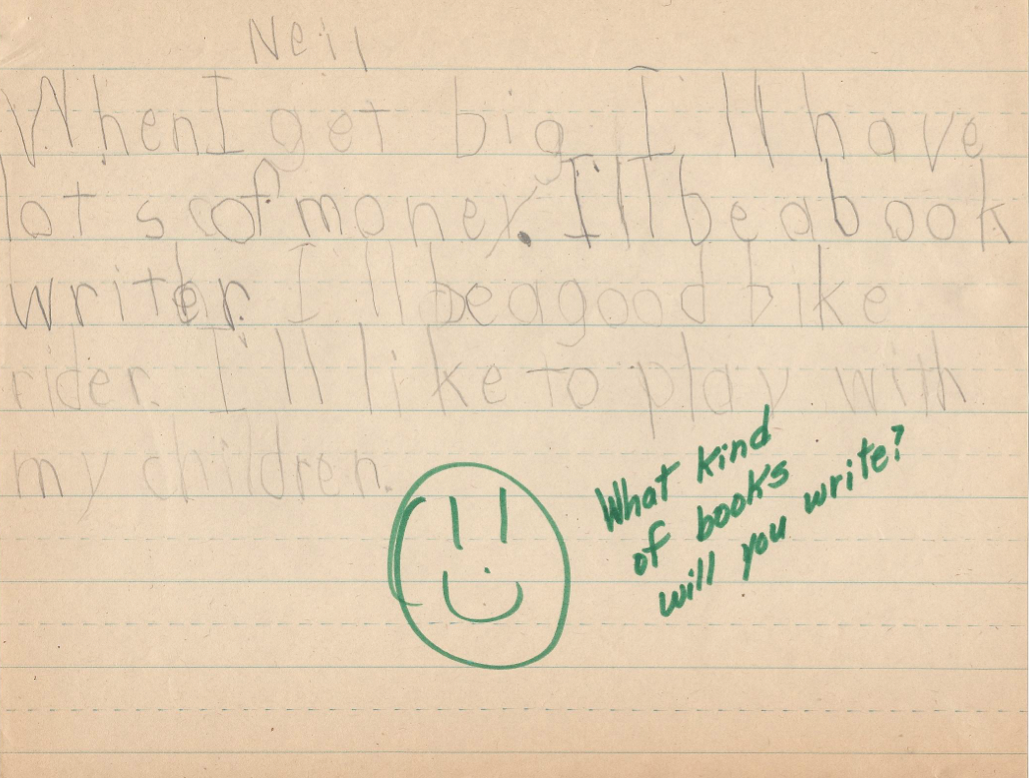

By second grade, I knew what I wanted to do with my life:

And by fourth grade, I had written half a dozen books, some of them with one of my few “friends” Chuck, and all of them atrocious.

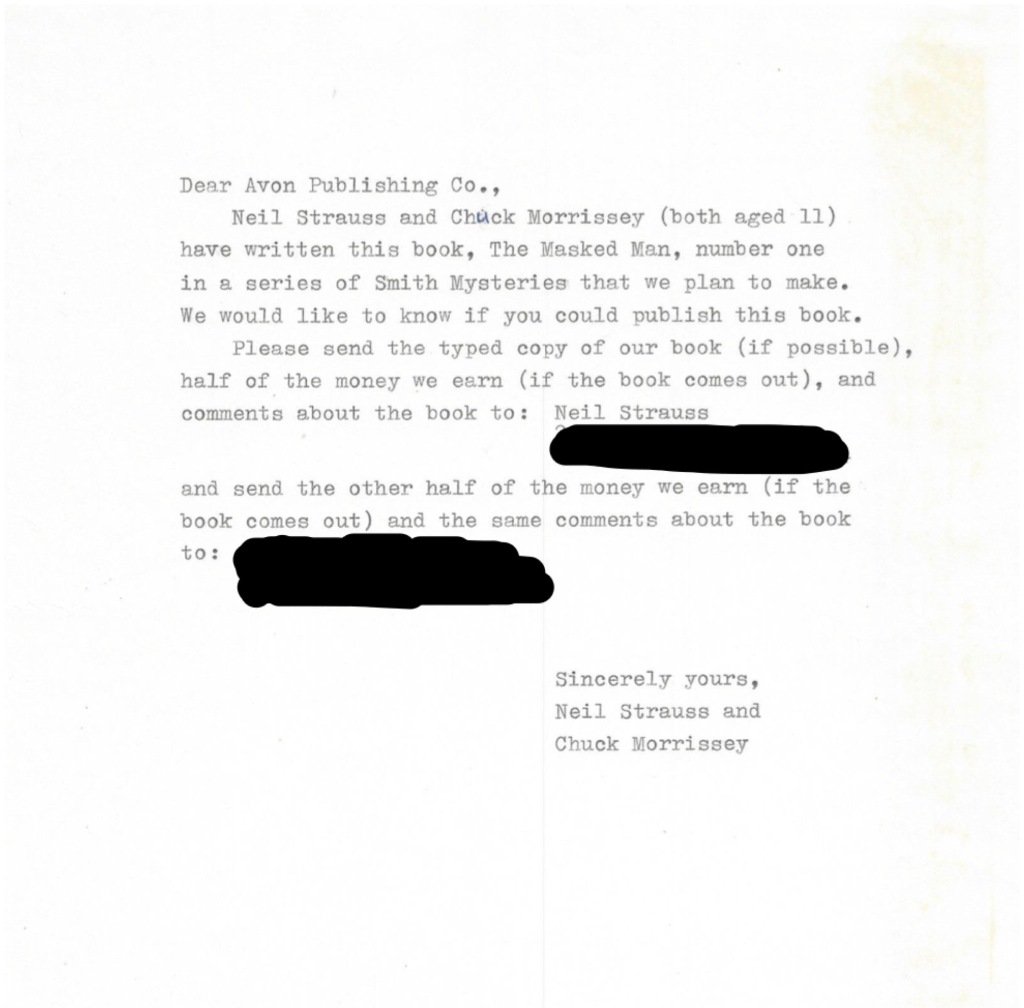

But I was so proud of them. I found a book with the names of agents and publishers in the library, and sent them my Hardy Boys-inspired “masterpiece”:

You’d think that they’d be touched to receive this hand-written submission from a couple of young, hopeful eleven-year-olds. Maybe they’d want to encourage a child’s dreams.

But…I didn’t get a single personal response.

It was the first of many rejections to come.

But I kept writing…and reading…and writing…and reading…and submitting my stories to magazines and journals with no success or even vague interest.

During my senior year in high school, there was a swim coach named Greg Baker. He was also one of the school’s English teachers. Before teaching, he was a swimmer training for the Olympics, but was partially paralyzed in a car crash and had to use a wheelchair:

He was teaching a course on James Joyce, which I wanted to take because every year after completing the book, he brought the students to his house to drink a Guinness Stout.

That probably wasn’t legal.

Anyway…when I read Ulysses, it blew my mind wide open: I didn’t know that it was possible to do so much with just words. It was not just a book, but an endless, bottomless puzzle: it was hypertext before there was hypertext.

And, as importantly, there were lots of dirty words, double-entendres, and sexual references in the book. It was amazing that art and literature could still be sexual and smutty. As an 18-year-old virgin, I definitely related to Leopold Bloom’s sexual frustration and obsession as well.

Since then, I’ve re-read the book every few years and I still find more in it every time. This is a page from my well-worn, obsessively marked-up copy:

It’s easy to tell which marks here I did when I first read it in high school: they’re the ones with all the dirty words underlined and annotated.

During freshman year of college in upstate New York, a friend of mine named Todd Polkes had gone to Manhattan to try out for an internship at a small avant-garde music magazine called Ear. They rejected him because they said he was too well-dressed.

As soon as he told me this, I knew the job was perfect for me, because I’m a slob. So I got the internship and began spending all my free time at the magazine, helping out in whatever way I could. No job was too low or small for me. That’s where I first really learned about writing and editing, and received the guidance and mentorship I needed, until I was finally published for the first time.

And I learned that the publishers and magazines were right to reject my early work: It sucked. I had the passion but not the knowledge or experience. The lesson: Just having a dream is not enough; just having a mentor or guide is not enough; just working hard is not enough. You need to be receptive, positive, and open: in short, teachable.

I still see the publisher of Ear, Carol Tuynman, to this day. Here we are just two months ago in Alaska, where she lives now:

With those first clips at Ear, I was able to send them to another magazine, Option, to get writing assignments.

At Option, they didn’t know I was a young college kid living in a dorm, and I never told them. I’d be on the phone with my editor trying to shut up everyone in the dorm so I could sound professional.

From Option, it was The New York Press. From the New York Press, it was The Village Voice, where Joe Levy, the editor there, truly taught me to write and appreciate good writing. Not much of this paid well (I got $75 a week at The New York Press), so I was sleeping on a sheet on a roach-inhabited floor because I couldn’t afford a mattress, but it was perhaps the most magical time of my life.

During senior year of college, I remember taking a girl on a date to a newsstand and showing her my byline in four different publications. It didn’t help, and I went home alone. In fact, I credit my career to my lack of social life and popularity. It gave me a lot of time at home alone to write.

The rest of my story, you can read on Wikipedia. That doesn’t mean it’s all true. But it’s at least more concise than this.

And because of how important Carol (and David Laskin) at Ear were, and Joe Levy at Rolling Stone, and later Jon Pareles at The New York Times, whenever I get a sincere, thoughtful email from a young writer who needs advice, I try to respond (if I’m not on a brutal deadline). Some of those writers have gone on to write New York Times best-selling books; others never mustered the discipline to finish a book.

To sum things up: If you’re having trouble finding your passion, try looking back on what you were doing when you were 11 years old or so. Was there anything meaningful you were doing that was just for you: Not for school and not for your parents?

That’s probably your passion.

I'll end this monster of a post with a quote from Joseph Campbell that I often think about and that ties everything here together:

“I feel if one follows what I call his bliss – the thing that really gets you deep in the gut and that you feel is your life – doors will open up. They do. They have in my life, and they have in many lives I know. And…if you follow your bliss, you will have your bliss, whether you have money or not. If you follow money, you may lose the money and then you don’t even have that. The secure way is really the insecure way.”

Thanks for reading. And if anyone is interested in reading Ulysses with me when I dive in next, let me know and we can launch a Steemit Book Club.

Verification: FACEBOOK TWITTER

And as for that skeleton, I found it in my father's closet when I was a teenager. It was a family sexual secret (most of them are), and it changed my life. I wrote a book about it called The Truth. It was the scariest thing I've ever done. My mother said: "If I'd known you were going to become a writer, I would have been nicer to you."

I think she was joking. Not sure though.

I believe that nearly every family has a skeleton in the closet. Some are more closely guarded than others. Hope you find yours, if you haven't yet, before it finds you.