Sleep can be considered 'one of the most easily communicated analogies to death'1 , and is 'as old as Western culture itself'2. This can be traced to classical Greek mythology, where Hypnos, the god of sleep, had a twin, Thanatos, the god of death3. Many examples of visual art and photography use a sleeping figure to represent the dead, and many other images contain a dead figure that is apparently sleeping. This text will investigate and examine a number of images where both the dead can be seen as sleeping and the sleeping are represented as dead.

The body of work produced by the field of post-mortem photography contains many images that portray the dead as though they are sleeping, and was a popular phenomenon in both the United States and the United Kingdom from the 1880s and beyond4. In such images, the dead were laid out on beds, or couches as though sleeping, sometimes surrounded by mementoes that 'often overwhelmed the body'5 .

The concepts of death and sleep in post-mortem photography are so deeply entwined that it is difficult to objectively analyse and comment upon such images if, as Susan Sontag suggests:

'All photographs are memonti mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person's (or thing's) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time's relentless melt.' 6

The relentless melt of time is a concept that is difficult to fathom. In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes provides an example in which the melt (of an image's meaning, value, or importance) is described. Barthes refers to a photograph of Lewis Payne taken in 1856. In that year, Payne attempted to assassinate the secretary of state, W. H. Seward. The photograph of Payne was taken in his cell prior to his execution. Barthes finds the image catastrophic, as 'he is going to die' 7 , but at the same time, Payne is already dead:

'This will be and this has been; I observe with horror an anterior future of which death is the stake. By giving me the absolute past of the pose (aorist), the photograph tells me death in the future.'8

By looking at the photograph of Payne in such a way, Barthes appears to support and strengthen Sontag's idea that all photographic images are memento mori, while also implicating the passage of time and notion of looking back (through time) at what has been and what shall be:

‘because each photograph always contains this imperious sign of my future death that each one, however attached it seems to be to the excited world of the living, challenges each of us’ 9

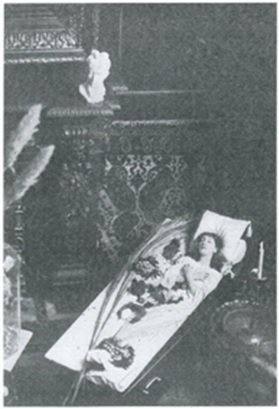

Photograph of Sarah Bernhardt in a coffin, unknown photographer, ca. 1870s

In early post-mortem photography the deceased were rarely represented in coffins, however, this practice become more popular as coffins became more exquisite and finely crafted. In the late 1800s, death was regarded 'as the last sleep'11 . As a result, the deceased were often represented in beds, surrounded by pillows and other fine fabrics.

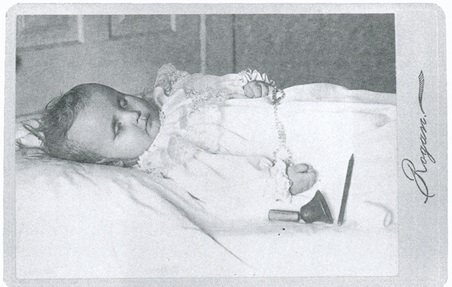

While there is no widespread evidence of others 'playing dead' for the camera, there is much evidence to suggest the popularity of post-mortem photography that depicted its subjects as though sleeping. Jay Ruby asserts that in particular, the post-mortem photographs of deceased or still born infants, the photographer's intent is to portray the subject as though sleeping, surrounded by pillows, fine ruffled sheets, and other elements of symbolism to suggest, but not conclusively assert that the subject has passed away. 12

A deceased infant ca 1870s, photographer unknown

A deceased infant ca 1870s, photographer unknownA shift in the representation of the dead in post-mortem photography occurred between 1880 and 1910, where 'the entire body, usually in a casket … [made] it impossible to pretend that the deceased were asleep, or “dead, yet alive”'13 . Such images are plentiful in Secure The Shadow. While the images do appear to carry a deep sadness, the subjects and individuals are unknown to the reader, and thus make it difficult to assign any personal emotion to the images. We believe that the people represented are dead due to the fact that they have been placed in a casket, and are sometimes surrounded by mourners. Ruby's commentary insists that the subjects are dead. However, armed with the knowledge that Sarah Bernhardt was alive when photographed inside a casket we can never be truly certain.

The post-mortem image therefore cannot be trusted as an object of undeniable truth, and raises many of its own problems and questions. It is however important to note that problems such as this are not as bad as it may seem. The uncertainty which surrounds many of the post-mortem images which Ruby discusses in Secure The Shadow allows the viewer to come to their own conclusions and connect with not only the images, but the people inside the images, even if it is in a somewhat disconnected and impersonal manner. It is my view that intimacy can only be achieved through the viewing of post-mortem photographs if the deceased is known to the viewer, as Walter Benjamin contends:

‘The cult of remembrance of loved ones, absent or dead, offers a last refuge for the cult value of the picture. For the last time the aura emanates from the early photographs in the fleeting expression of a human face. This is what constitutes their melancholy, incomparable beauty.’14

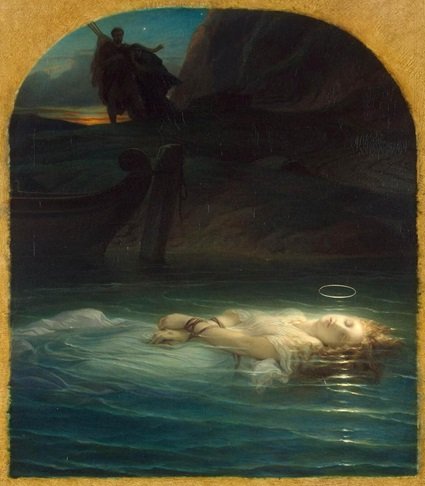

It is not only in post-mortem photography in which the dead appear to be sleeping. In The Young Martyr (1853), by French painter Paul Delaroche, a young, beautiful woman is represented as being dead. Delaroche’s image depicts a young Christian Martyr drowned in Rome’s Tiber River, hands bound, and laden with other symbolism 15. The halo that appears above the subject's head indicates that that she is radiant and sanctified, unlike Millais' Ophelia who was viewed as nothing more than a 'poor wretch' 16.

Paul Delaroche, The Young Martyr, 1853

Paul Delaroche, The Young Martyr, 1853The Young Martyr remains an important image due to its religious content. Unlike the post-mortem photographs in Secure The Shadow, Delaroche’s painting resonates and connects with a much larger audience due to what it depicts. It is, however, distinctly different from any photograph – it beautifies the deceased and makes her appear radiant, innocent and a subject to be pitied.

Another example, in which the dead are represented as sleeping is evident in Linda Bergkvist's Gone Gone can be seen as 'peaceful yet sad, because the character depicted is no longer alive'18 . The character appears peaceful, but there are many symbolic hints as to the character's lack of life – the first of these is obviously the title, but as the artist explains - 'I think it was in the skin tone that made the difference. Or perhaps the textures.'19

Gone is a peaceful, but complicated image. While it can be referred to as beautiful, it is a fictional representation that is difficult to view because of what it represents – a death, the death of the other. Nonetheless, Gone resonates due to its use of symbolic elements that are drawn from fundamental associations that have been formed by Western Culture throughout history, especially so, the rotting foliage.

Sleep and death remain linked not only through images, but also through language. Kastenbaum notes that ‘Some people today still replace the word death or dead with sleep when they want to speak in a less threatening way.’20 By comparing the state of death to the state of sleep, we can more easily come to terms with the concept of death. Unlike sleep, however, death is considered a permanent and irreversible state.

References

1. Kastenbaum, Robert. Death, Society and Human Experience, 5th edition, Needham Heights: Allyn & Bacon / Simon & Schuster, 1995, 39.

2. Jay Ruby, Secure The Shadow: Death and Photography in America (MIT Press, 1995), 63.

3. Ibid.

4. Barbara P Norfleet, Looking At Death (David R Gordine Publishers Inc, 1993), 96.

5. Ibid.

6. Susan Sontag, On Photography (Penguin Books, 1979), 15.

7. Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (Vintage Classics, 2000), 96.

8. Barthes, 96 [Emphasis in original].

9. Barthes, 97.

10. Eve Golden, “From Stage to Screen: The Film Career of Sarah Bernhardt” http://www.classicimages.com/past_issues/view/?x=/1997/june/bernhard.html

11.Ruby, 72.

12. Ruby, 65.

13. Ruby, 72.

14. Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, (New York: Random House, 1968), 220.

15. Regina Haggo, “Martyrs to their art: painters make saints sexy [Final Edition]” The Spectator, December 28, 2002. http://www.proquest.com/

16. Kimberly Rhodes, “Degenerate Detail: John Everett Millais and Ophelia's Muddy Death”, 44.

17. Haggo, “Martyrs to their art: painters make saints sexy.”

18. Linda Bergkvist, “gone” http://www.furiae.com/popup.php?image=gone)

19. Ibid

20. Kastenbaum, 39.