“If pictorial expression has changed, it is because modern life has necessitated it...The view through the door of the railroad car or the automobile windshield, in combination with speed, has altered the habitual look of things. A modern man registers a hundred times more sensory impressions than an eighteenth-century artist... The compression of the modern picture, its variety, its breaking up of forms, are the result of all this.” – Fernand Léger quoted in 1914.

“The Habitual Look of Things”

New technology drives new habits of perspective. At the turn of the 19th century, automobiles, ships and railways were disruptive forces that re-calibrated the ways in which we mediate the world around us. Global was beginning to become local, economically, culturally and artistically. There are striking similarities found in the language of artists like Fernand Léger in 1914 that mirror today’s discussions of augmented, virtual reality and blockchain among others. The first part of this article will look towards examples of the past as a way of better understanding today’s momentum towards the future.

Bright Lights Big City

Léger painted “The City” in 1919, shortly after the first World War. (Pictured above.) The massive 8’ x 10’ painting provoked a new wave of post-war art that attempted to capture the motion and growth of a technology infused urban landscape.

France was an exciting cultural and technological canvas for artists like Léger to explore. He captured the dynamism of the Parisian street with a vibrant color palette depicting a collage of motion, growth, scaffolding, shopfront-windows, street lights, sounds and bright metallic materials. It was completely overwhelming to an eye or ear that had not experienced such intense contrast. “Hundreds” more sensory impressions were being digested at once than someone experiencing the same city just a decade or two earlier. Advancements made in transportation, electricity, metallurgy and construction pushed senses to new norms. Paris was moving faster, building larger and connecting greater with the world around it.

Just a few years before Léger’s Parisian landscape appeared, Europe was immersed in World War 1. Wartime had fractured economies of the 19th century, while simultaneously triggering new ones. Popularly referred to as the “war of movement” - WWI infrastructure was integrated at an unprecedented scale and connected places that were once distant and unrelated. One major device of connectivity was the the Trans-Siberian Railway (depicted below in 1913) which provided a compression of places and environments across an unprecedented 9,289km distance. The rail line played a powerful role in transporting wartime materials and immigrants between Europe into portions of Asia.

Culture and geography were being juxtaposed through a single cab-window, blending scenery of urban and rural, breaking up a legible transition between one city and another and warping the time expectancy between places.

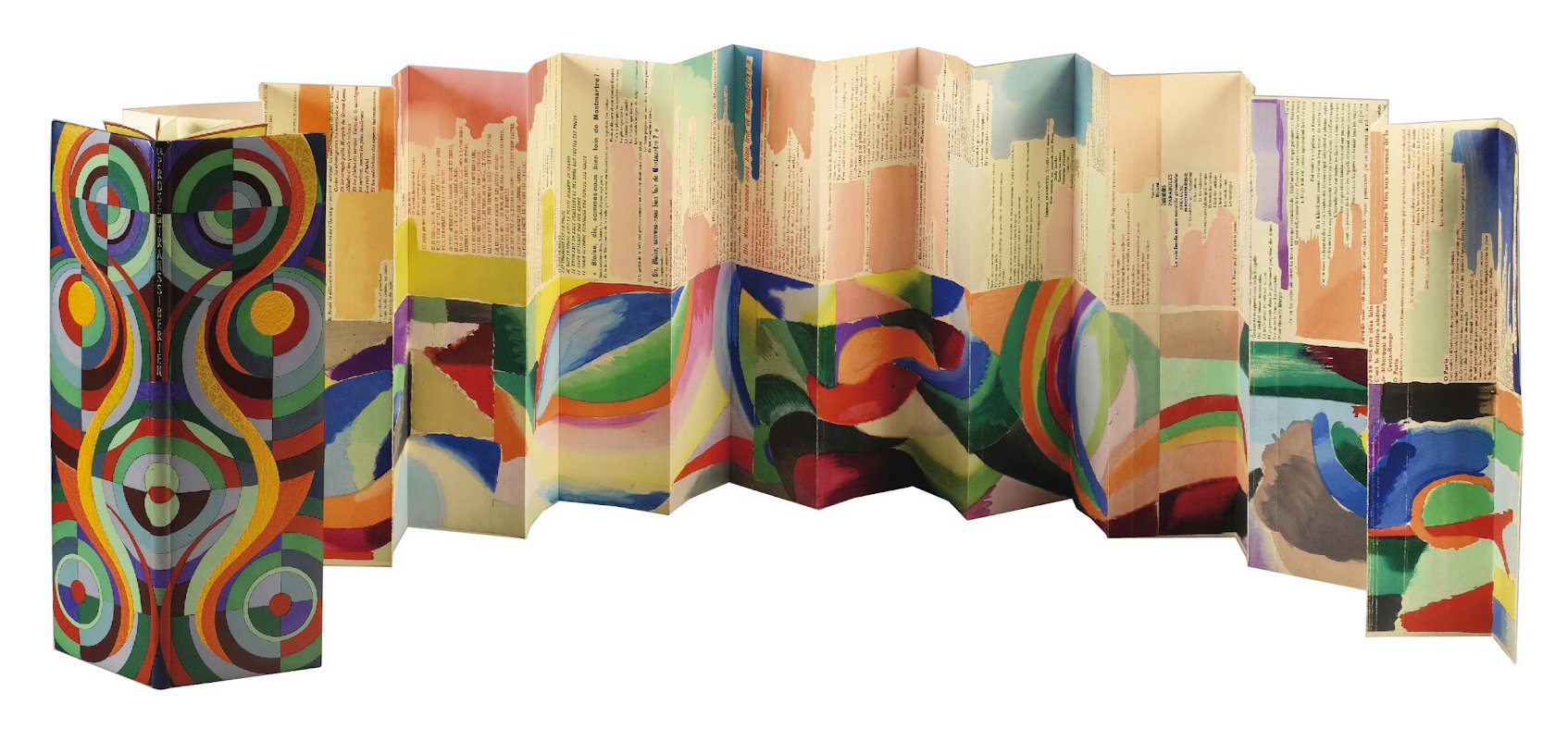

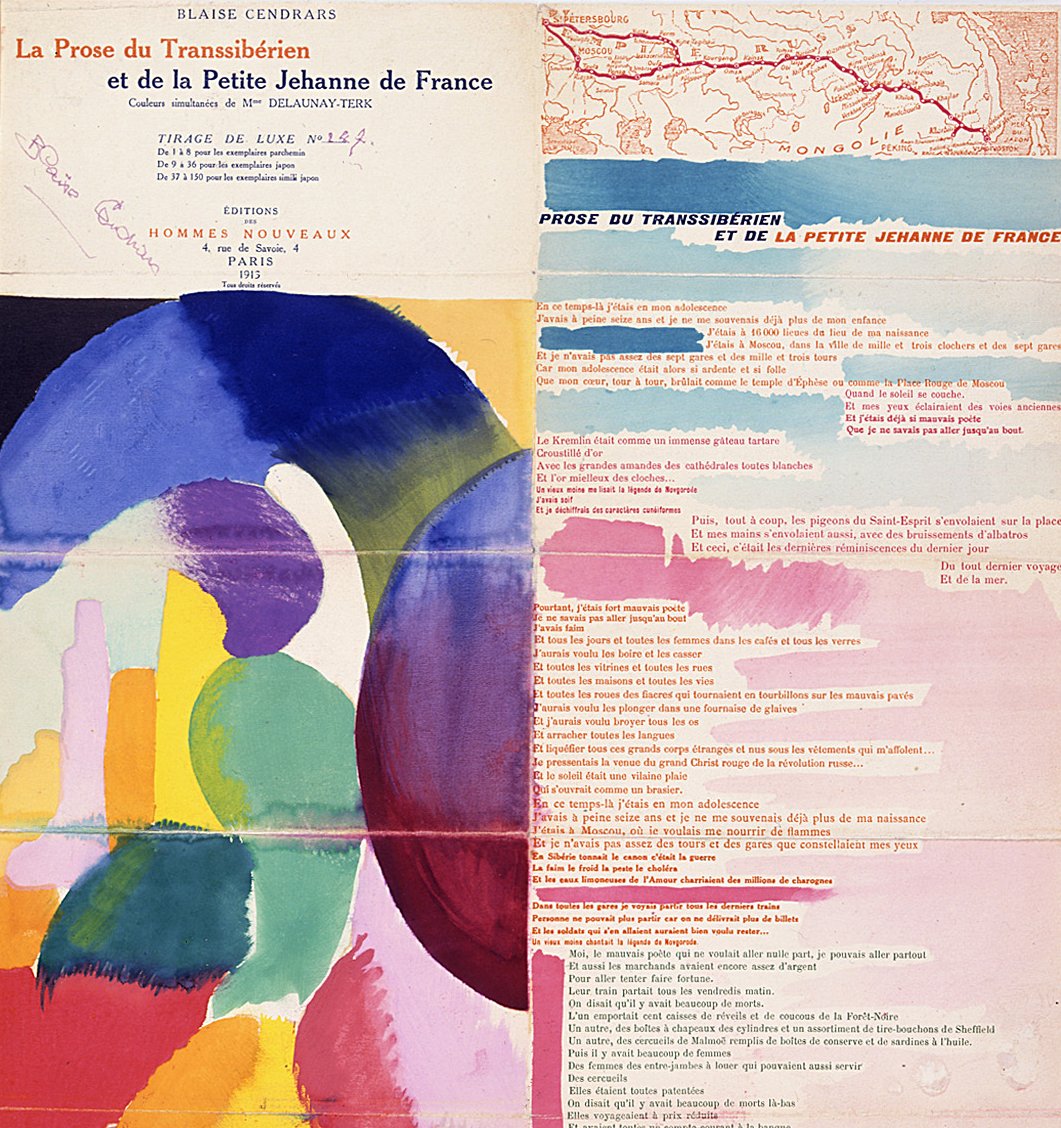

“La prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France” or “Prose of the Trans-Siberian and of Little Jehanne of France” (pictured above and below) was a collaborative art project that paired poetry and painting. Writer Blaise Cendrars wrote a poem about a journey through Russia in 1905 while aboard the Trans-Siberian Railway. The modernist poetry depicted the chaotic wartime story of a 16-year old travelling by train during the Russian Revolution of 1905. Artist Sonia Delaunay painted directly on top of the poetry creating a collage of bright colors and textures. Her use of contrast and form was purposefully composed to generate a sense of movement and disorientation as the story unfolded.

"The intensity of the colour field is heightened in accordance with the law of simultaneous contrast: orange seen next to green becomes more red, while green seen next to orange appears more blue. These constant two-way influences create an unusual vibration in the eye of the viewer. Delaunay read this phenomenon as movement and rhythm and understood it as the painting appropriate to a modern society in motion." - Hajo Düchting (The Triumph of Color)

New Culture of “Simultaneity”

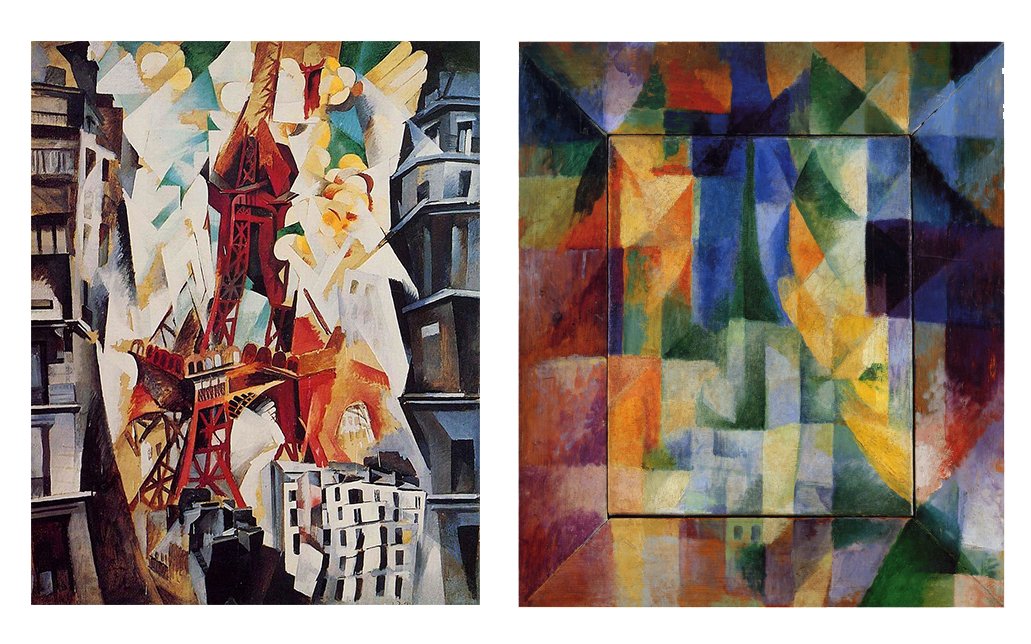

A creative husband and wife duo, Sonia and Robert Delaunay; coined the term “Simultaneity” with the introduction of Robert’s painting “Simultaneous Windows on The City”. Here, contrast was celebrated. The canvas (shown below, left) reveals a collaged frame of color and fractured cityscapes. The Delaunay’s fully embraced the chaos in cities and on canvas, while looking creatively for ways in which that chaos could be re-appropriated into something different. Sonia, below, describes her process of incorporating Ukrainian vernacular in making a quilt...

"About 1911 I had the idea of making for my son, who had just been born, a blanket composed of bits of fabric like those I had seen in the houses of Ukrainian peasants. When it was finished, the arrangement of the pieces of material seemed to me to evoke cubist conceptions and we then tried to apply the same process to other objects and paintings." - Sonia Delaunay

Contrast was hot in the Nineteen-Teens. The Delaunay’s were like first generation mashup artists. They loved combining seemingly distant textures and uses. Sonia in particular loved to challenge the traditional application of pattern and material. She wore outrageously colorful clothing with strong, collaged geometric shapes. Her explorative pop-style work quickly broke free of the rules that bound artists to an wood easel and white canvas. Sonia’s work drove innovations in both the pop art movement and feminism of the later 20th century.

The duo collaborated on many different artistic and industrial mediums; from pamphlets to paintings and quilts to cars.

Visual Mash-up

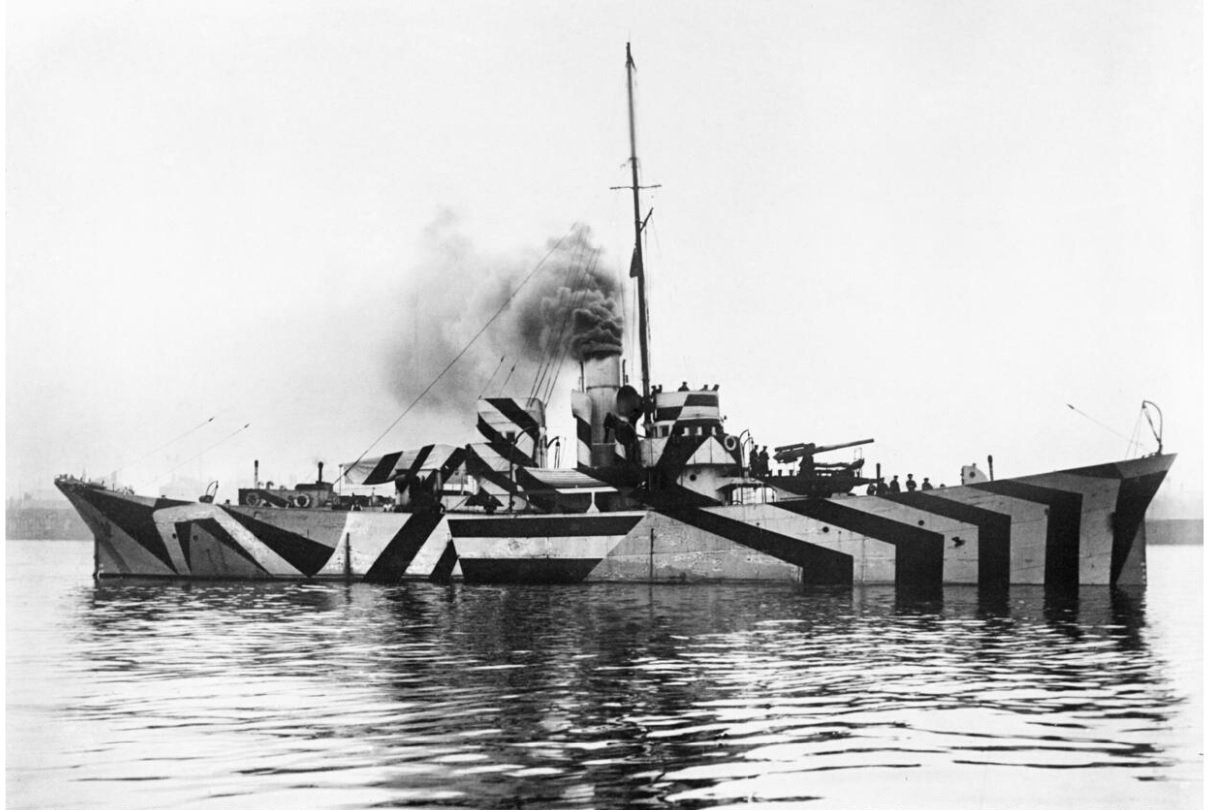

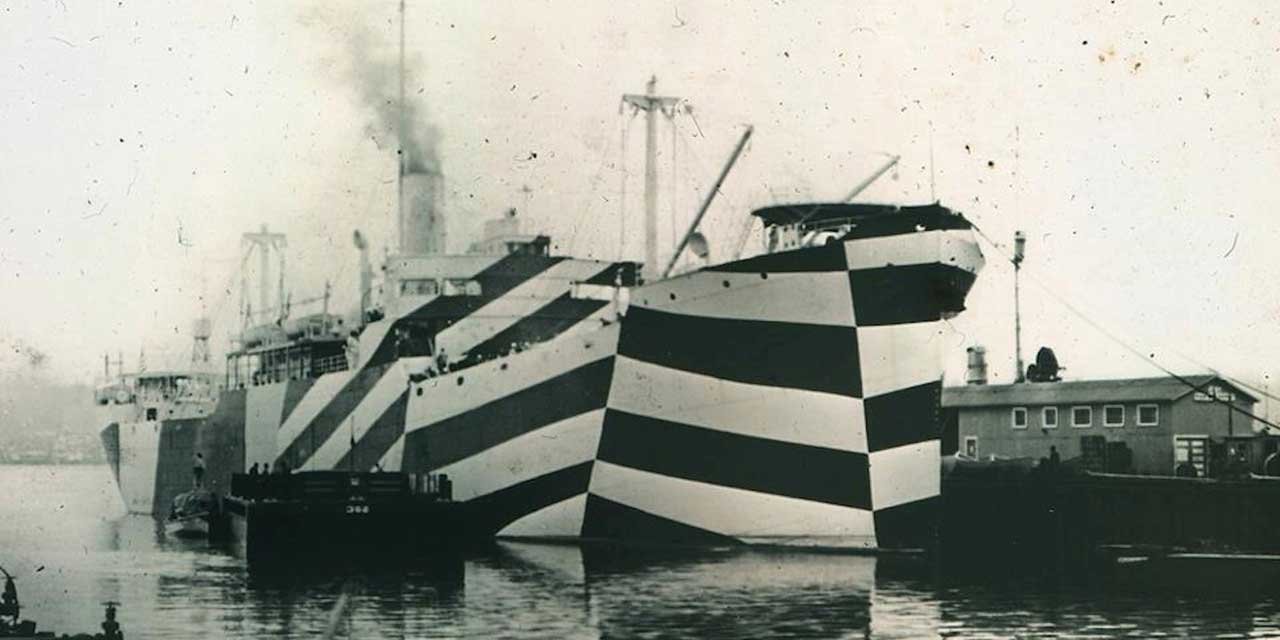

Pattern played a powerful role in the early 1900s, blurring the lines between art, industry and even military. “Razzle Dazzle” was a militarized camouflage strategy used in World War 1 to make it difficult for enemy ships to determine a target’s distance. The crisscrossed hatchwork made surfaces look as though they were falling away at varying perspectives. What was fascinating about this strategy was that it had been developed by an abstract artist, Edward Wadsworth. During his time in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, Wadsworth developed his Dazzle patterning by taking cues from other cubist artists (like the Delaunay’s) of the same time period.

Dazzling artistic mashups like those of the Delaunay’s explored roles of perception and their subsequent influences on cultural fabric. The effects of faster travel via the Trans-Siberian Railway catalyzed disruptive movements at a localized scale through interpreting something global. Changes in the tools we use to communicate in turn, alter the mediums with which we share, explore and collaborate. Now, 100 years later - we are facing the next big shift hovering right around the corner...

Stay tuned for Part 2 of this Futures Series, where I’ll look forward and explore Virtual Futures : Anarchy in Digital Urbanism…

follow me @voronoi | design collective @hitheryon