And now for something slightly different. @didic posted a contest a few days ago, challenging participants to write a book review of a fantasy or sci-fi novel, published no earlier than 2010. At first I was stumped. I have read my share of Asimov and Heinlein in my day, but they can hardly be called contemporary. Then I remembered I have recently binged-read all the Tiffany Aching books by Terry Pratchett and as much as I may think of the Discworld as a real place, it’s actually fantasy.

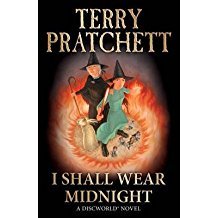

I will readily come out and say that Terry Pratchett is one of my favourite authors. I own almost all of his books and they have a place of honour in my bookcase. From the Night Watch series to the Witches series, I love them all (although the Rincewand books do take a very far back seat). But none of them move me as much as the Tiffany Aching series. For this review I have chosen I Shall Wear Midnight, not only because it was published in 2010 and therefore qualifies for this contest, but also because it’s my favourite of the series.

This book review will be part book review and part me gushing about how much I love Tiffany Aching. @didic specified he wanted us to review a book we love, and he needn’t fear. I unabashedly love this book.

Tiffany Aching

Tiffany is a witch. At nine years of age, she travelled into the Fairy land, defeated the Fairy Queen with a frying pan and rescued the Baron’s son from the clutches of the fairies. She didn’t realise she was a witch then, and she subsequently received training to become one. She made some mistakes – she danced with the Winter and spent a whole book trying to put things right – but in I Shall Wear Midnight she has become quite a powerful witch. Even if she is only fifteen.

Tiffany is the witch of the chalk and she flies back and forth on her broomstick trying to mend all ills in the villages which form part of her steading. She is busy – probably too busy for her own good. Being a witch is not all doing spells and throwing magic around, it usually means helping with births, deaths and illnesses. She takes responsibility and does what needs doing, even though it’s often a thankless job.

Being a witch meant you had to make choices, usually the choices that ordinary people did not want to make or even to know about.

Tiffany has some help in the form of the Nac Mac Feegles. How to describe these fierce little men? They are small, incredibly strong, completely blue and they speak a language that sounds very much like Scottish.

The life of all the other Feegles was generally about fighting, stealing and boozing, with a few extra bits like getting food, which they mostly stole, and doing the laundry, which they mostly did not do.

The story

Witches have generally been respected on the Discworld. Even Tiffany has gained the respect of the people of the Chalk, even though they are not used to witches there. But lately the tide has started to turn. When things go wrong, people start blaming the witches. Strange, slanderous stories start making the rounds about witches, and everyone becomes suspicious. When Tiffany goes into the big city to find the Baron’s son, she encounters a man with no eyes, from which a stink emanates – the stink of hatred and evil. Everywhere he goes, people turn on witches.

The Cunning Man has been summoned. No one knows how, but he is after Tiffany and she has to defeat him. She has to be careful, because if he takes over her body, there is no hope for her anymore. But not only does she have to fight the Cunning Man, she also has to defend herself against baseless accusations that she has killed the Baron and stolen money. Luckily she has the support of the other witches, notably Granny Weatherwax. And the Nac Mac Feegles are never far behind, always ready to help out their "hag of the hills".

Feminism

There are so, so many things I love about this book, so I will try to highlight a few. First, this book is very feminist. Tiffany is a fifteen year old girl. Granted, she is a witch, and a powerful one at that, but she is on her own. She takes responsibility for her mistakes, she keeps her people safe and she doesn’t expect credit for anything. When she rescued Roland, the Baron’s son at age nine, no one on the Chalk could believe that a nine-year-old could be capable of rescuing a boy a couple of years her senior. And so the story got changed: it became Roland who had rescued Tiffany. She never contradicted anyone and didn’t insist on getting any of the credit. But finally, three books later in I Shall Wear Midnight, the Baron acknowledges Tiffany’s feat of heroism on his dying bed.

There is also the issue of Roland himself. Tiffany and Roland had become close and everyone assumed they had an understanding. But then he got engaged to be married to someone else, a fact that bothers Tiffany, even though she is not particularly in love with Roland. She is resentful of the future wife of Roland, Letitia, and a little jealous too. But the story doesn’t dwell on this too long. This is not about whether Tiffany will get her happily-ever-after ending or whether she will win Roland back. She realises that they were never meant to be, and she also gets to know Letitia and realises that there is far more there than meets the eye. Where so many other YA novels fall into the girl-fighting-girl-for-boy trope, I Shall Wear Midnight skims this trope slightly and then deftly changes the story in a much more interesting direction.

Evil thoughts

Poison goes where poison is welcome.

It’s one of Granny Weatherwax’s expressions, and Tiffany needs to remind herself of this as more and more of her friends and acquaintances turn against her. She is falsely accused of witchcraft, as if it is something evil, and not helping people out. Even Roland turns against her. Tiffany has to remind herself not to retaliate, but to remember that these people have been turned by the Cunning Man. She has to rise above it.

While Terry Pratchett’s books are fantasy, there is a lot of satire in them as well. Even in this book you can see analogies with our current culture and political climate. The sudden suspicion of the “other”. Witches are different, they stand outside of society. They serve uncomplainingly and don’t ask for anything in return. And every so often, people turn against witches inexplicably. Stories are told, suspicions are whispered and soon every lost animal, every sickness, every death is blamed on the witches. It is the work of the Cunning Man, whispering lies in the ears of those who will listen, poisoning their minds until they turn on people who have never done them any wrong. Although this book was written in 2010, I don’t have to spell out that we have our own Cunning Man in our midst right now.

The problem with assigned roles

When Tiffany tries to find out where the Cunning Man comes from – and even more importantly, how to defeat him – she gets to know Letitia better. Letitia, who she always viewed as a sniffling, soppy girl. It turns out that she is anything but that. Sure, she is the pretty blonde picture perfect of a princess, but underneath it all she is actually a witch. An untrained witch, which is the most dangerous witch of all. And she has inadvertently caused all these problems for Tiffany.

Tiffany and Letitia commiserate over a fairy tale book they both had as a child and they realise that the book is at the root of their problems. The book, which told little girls what their role would be in life.

[...]she had seen through it. It lied. No, well, not exactly lied, but told you truths that you did not want to know: that only blonde and blue-eyed girls could get the prince and wear the glittering crown. It was built into the world. Even worse, it was built into your hair colouring. Redheads and brunettes sometimes got more than a walk-on part in the land of story, but if all you had was a rather mousy shade of brown hair, you were marked down to be a servant girl.

Or you could be a witch.

During the time she laments not becoming Roland’s chosen girl, she knows it’s because mousy girls don’t become princesses. The stories say this is so. Letitia has the opposite problem: her blonde hair and blue eyes destine her for being a princess, but all she wanted was to be a witch. The lesson here is clear: we need more diversity in stories and we need to allow our children to be anything they want or they will inadvertently unleash a holy terror on the world.

Language

I will cap off this review with a few words about Terry Pratchett’s wonderful use of language. You would think that a story about a fifteen-year-old witch would be something that is only of interest to children. I hope I have already shown above how layered this book is and how much an adult can enjoy it too. But apart from Terry Pratchett’s gift of storytelling, he has an amazing gift of language too. The book is peppered with beautiful sentences which will make you laugh and cry and get angry. In wordsmithery Terry Pratchett is comparable with P.G. Wodehouse, which is high praise indeed. While Wodehouse wrote in an entire different genre (and an entirely different era), the craftmanship that both authors put into each sentence is astonishing. I will leave you with this bit, which is about the carved outline of a man in the chalk on the hill.

Oh, and he had also been carved, or so it would appear, before anyone had invented trousers. In fact, to say that he had no trousers on just didn’t do the job. His lack of trousers filled the world.

I could go on and on about this book, and about Terry Pratchett in general. I would really recommend you give him a chance. You don't need to read the series in order, although it would help put things into perspective. While the Rincewand stories are the first Terry Pratchett wrote, I would not recommend starting with those, they are not the best. My favourite are the Tiffany Aching series (which atarts with The Wee Free Men) and the witches series (which starts with Equal Rites) as they so unabashedly celebrate women.