*6 min read *

More people are learning that in academia progress is too often fought against and even suppressed, not due to any conspiracy necessarily (these exist too), but more often, I believe, due to the fear of losing tenure (university politics) or the pain of having years of your own research made moot.

It seems an unfortunate habit of humans that when they form groups, personalities play games of domination, even at universities. We call it politics, and apparently it's more important than working together to find the truth. I cannot hate professors though especially since my family is full of them. I can't even hate the ones that bury their heads in the sand for fear of ridicule or losing their jobs, instead of acknowledging inconvenient discoveries. After all, people have families to feed.

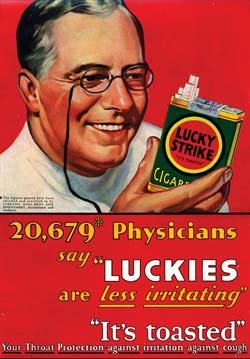

However, too many of us are so naive that we automatically believe a consensus must be true if it is supported by a majority of experts. This is a logical fallacy. If we ever learned from history we'd know that technological or scientific revolution often happens despite the majority consensus deeming it impossible. The Earth is not the centre of the universe. "Blasphemy! Arrest that man!" Smoking is bad for you. "Absurd! The majority of doctors agree smoking is good for you!" Modern financial theory is based on false assumptions and doesn't fit the data. "Shut up hippy! Economics is real science!"

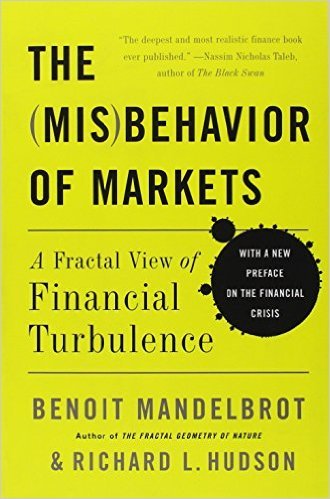

In this week's market exploration I'll provide a brief summary of Chapter 12, "Ten Heresies of Finance" from the book The (Mis)behavior of Markets by Benoit Mandelbrot. Mandelbrot was a French mathematician. He pioneered the mathematics of fractal geometry and coined the term "fractal." His work revolutionized a wide range of disciplines from neurobiology, to meteorology, to computer graphics, to finance. If you haven't heard of the Mandelbrot set, I'm jealous. Smoke a bowl and watch this. The Mandelbrot set is a simple equation on the complex plane (math speak) that produces an endless array of self-similar but unique patterns of great beauty and complexity, reminiscent of nature.

My intention is not to argue a point or convince you of anything, only to provide a brief summary of the chapter with the hope of saving you some time. If you find this information useful or hard to believe, I highly recommend reading the book. He is a much better writer, the ideas are fascinating, and his argument is convincing. In as few of my own words as possible:

1. "Markets Are Turbulent."

Turbulence "proceeds in bursts and pauses, and whose parts scale fractally." There is "long-term dependence so that an event here and now affects every other event elsewhere and in the distant future." Price changes "in a wild kind of variation far outside the normal expectations of the bell curve; in a concentration of changes here and there; in a discontinuity in the system jumping from one value to another; and in one set of mathematical rules that can, in large measure, describe it all."

2. "Markets Are Very, Very Risky-- More Risky Than the Standard Theories Imagine."

Orthodox economists place too much importance on the average, ignoring the impact of extreme events that lie outside the bell curve. "Turbulence is hard to predict, harder to protect against, hardest of all to engineer and profit from." The bell curve is not "a realistic yardstick for measuring the risk." Price variation is dominated by rare extreme fluctuations with distribution curves lying far outside the Gaussian standards. "According to the standard model of finance, in which prices vary according to the bell curve, the odds of ruin are about . . . one chance in a hundred billion billion."

3. "Market 'Timing' Matters Greatly. Big Gains and Losses Concentrate into Small Packages of Time."

Nature is not smooth and continuous, it's jagged and clustered. During the decline of the dollar against the yen from 1986 to 2003, "nearly half that decline occurred on just ten out of those 4,695 trading days. Put another way, 46 percent of the damage to dollar investors happened on 0.21 percent of the days." Volatility in the market is concentrated.

4. "Prices Often Leap, Not Glide. That Adds to the Risk."

"Continuity is a fundamental assumption of conventional finance." If you've ever watched real-time ticker-tape, you'd know that "prices do not rise smoothly from one cent to the next; they can easily jump many notches at a time."

5. "In Markets Time is Flexible."

The Capital Asset Pricing Model assumes all investors think alike "holding the securities in question for exactly the same length of time." With a fractal view, different time-scales don't have different risk. "The same risk factors, the same formulae apply to a day as to a year, an hour as to a month. Only the magnitude differs, not the proportions."

"Statistically speaking, the risks of a day are much like those of a week, a month, or a year. But the price variations scale with time."

6. "Markets in All Places and Ages Work Alike."

"In a market there is, I believe, a spontaneous internal life, an inherent activity that comes from the way people come together, organize themselves in banks or brokerages, and exchange assets. This internal process does not make prices on its own; but it is certainly part of the price-setting mechanism." Fractal geometry, "the study of patterns, in space or time, that remain the same even as the scale of observation changes," is an example of invariance in the natural world. "One of the surprising conclusions of fractal market analysis is the similarity of certain variables from one type of market to another."

7. "Markets Are Inherently Uncertain, and Bubbles Are Inevitable."

"With financial prices, scaling means that the odds of a massive price movement given a large one are akin to those of a large movement given a merely sizeable one." Scaling "makes decisions difficult, prediction perilous, and bubbles a certainty." For more about chance and uncertainty in the market read Nassim Taleb's work.

8. "Markets Are Deceptive."

"People want to see patterns in the world," even if there are none. An important skill but one that can lead to self-deception in the market. "By sheer operations of chance, one might easily see a three-wave, fifty-year pattern emerging over a century and a half of data." Let that sink in. "Chance alone can produce deceptively convincing patterns." This doesn't mean that charts don't have patterns, but "it is a bold investor who would try to forecast a specific price level based solely on a pattern in the charts."

9. "Forecasting Prices May Be Perilous, but You Can Estimate the Odds of Future Volatility."

"The data overwhelmingly show that the magnitude of price changes depends on those of the past, and that the bell curve is a nonsense." Volatility clusters, but "forecasting volatility is like forecasting the weather." It is probably possible and it is a problem researchers are currently working on. If volatility can be forecast, this is good news for people who manage or profit from risk.

10. "In Financial Markets, the Idea of 'Value' Has Limited Value."

Financial analysts try to calculate value or model it, which "implies that value is somehow a single number that is a rational, solvable function of information." Value "is a mean, an average, something certain in a chaos of conflicting information. People like the comfort of such thinking." Is this useful to calculate value with Price-earnings ratios or hard assets etc.? "Surely the 'real' value [of any company] changes every month, every week, every day--even tick-by-tick . . . and if that value changes constantly, then of what practical use is it . . . ?"

There is such a thing as intrinsic value, but in turbulent markets it is "a slippery concept, and one whose usefulness is vastly over-rated."

A true scientist understands a theory is never the truth but only a tool to further an investigation. A theory is a tool that must be either totally refuted or encompassed by a broader theory if progress is to be made. This process of learning is never ending and any conclusion is an imaginary concept. In a universe flowing like a river, alive and complex, every conclusion, belief, or opinion is a static image, always partial and dead to the new.

If I've made a mistake or if you disagree, I'd love to hear what other traders and market enthusiasts think. I'm not an expert nor am I advising you. Have a great week!

Follow @skypal for weekly posts about markets and life.