I recently had an opportunity to review Cardano’s Ouroboros consensus algorithm as presented in a youtube presentation. The original paper can be found here. The marketing behind Cardano and Ouroboros is that it is the first “peer reviewed”, “provably secure” proof of stake consensus algorithm. Upon reading their paper it becomes clear to those familiar with BitShares 1.0, Graphene, Steem, and EOS that Ouroboros is a copy of Delegated Proof of Stake (DPoS) with a few counter-productive modifications. In fact their paper refers to the term “πDPoS” 17 times without mentioning or recognizing any of my prior work.

Before getting into the more technical review of Ouroboros, let’s look at the performance of the final product.

Block Interval

Block interval determines the latency until a transaction is included in the first block. This is the lower-bound on the responsiveness of decentralized applications built on the protocol. Applications like Steem and BitShares are not really viable unless there is low latency and high certainty of finality.

EOS: 0.5 seconds

Steem/BitShares: 3 seconds

Ouroboros: 20 seconds

Irreversibility

This is how long someone must wait to be certain that a transaction will not be undone by a new/longer fork being released that excludes the transaction. Irreversibility is very important for any multi-step transactions. You don’t want to ship goods until payment is confirmed. You cannot make one trade until the prior trade is locked in. A decentralized exchange is not viable on a platform that has significant latency until irreversibility.

EOS: <= 2 seconds

Steem/BitShares: <= 45 seconds

Ouroboros: > 5 hours

Ouroboros is Unfit for Decentralized Applications

If we assume Ouroboros is actually “more provably secure” by some definition of secure, it is of little practical value because as specified the security completely compromises the practically. It would be like claiming a bullet proof vest is “provably safe” but it weighs 400 pounds. At some point other factors of system design take priority.

Unfortunately we cannot simply assume it has been proven secure. I will demonstrate that despite claims to the contrary, Ouroboros is far less secure due to faulty assumptions in its design. In other words, Ouroboros is a 400 pound bullet proof vest that doesn’t actually stop the real bullets.

Components of Delegated Proof of Stake (aka Ouroboros)

The Delegated Proof of Stake algorithm is divided into two parts:

- Selecting a set of block producers

- Scheduling the producers into time slots

The process of selecting block producers is typically derived from proof of stake which may be delegated. The set of block producers is periodically updated. In BitShares this happens every maintenance interval (1 hour), in Steem and EOS it happens every round (N blocks where N is defined as the number of producers in the set). In Ouroboros it happens every 5 days according to Charles Hoskinson in an interview where he describes the protocol.

Once the set of producers are selected they are assigned to time slots where a producer can either produce a block or not. The chain with the most consensus will have the fewest missed blocks and therefore be the longest chain. In ouroboros they call this the “density” of the chain, but the concept is the same.

Selecting Block Producers

Under Ouroboros anyone who wants to be a producer can be selected for a slot proportional to the amount of stake they own or is delegated to them. This is similar to how Steem selects 1 producer in every set (aka every minute). Whereas Steem only schedules 1 out of every 21 time slots in this manner, Ouroboros schedules all time slots with this mathematical distribution. In the case of Ouroboros only those with at least 1% of stake delegated to them are eligible to be in the set of producers, but Steem places no lower limit.

Scheduling Block Producers into Slots

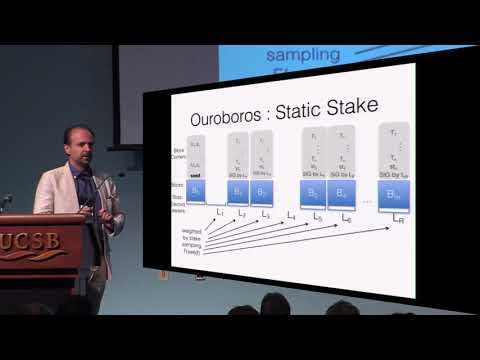

The primary difference between Steem and Ouroboros’ system is that Steem uses deterministic scheduling with pseudorandom shuffling and Ouroboros uses sampling from a source of provable randomness created by a committee of randomly selected stakeholders. Oroboros places a very strong focus on the need for a trustless source of randomness in order to ensure the producer schedule isn’t manipulated by block producers manipulating the block contents so as to control the schedule.

Security Concerns addressed by Randomness

The heart of blockchain security is knowing that during every confirmation window that a diverse set of unlikely-to-collude entities produce blocks. Time to irreversibility depends upon how long it takes to get input from a 2/3+ majority of potential producers.

If the order of producer scheduling can be controlled by the producers there exists a circular dependency. This is the origin of the name Ouroboros (a snake eating its own tail). The focus of the Ouroboros design is to ensure that 2/3+ honest producers can be scheduled without interference. This is why they lock in the set of producers for days and schedule them with a set of provable randomness that no party can manipulate.

Steem / BitShares / EOS

Existing DPOS chains select a set of unlikely to collude entities by approval voting and then schedule them in a pseudorandom order. This shuffling is not really needed because once each of them participates a single block a 2/3+ consensus can be determined. This is why EOS will be removing the random shuffle all together.

With Ouroboros the length of time until 2/3+ of the stake is “randomly selected” is not known. It is entirely possible that in some windows all block producer slots will be randomly assigned to the same producer. While this is statistically unlikely, it is not unreasonable to presume that a long sequence of blocks could be assigned to collusive peers.

You can think of the process of confirmation on Ouroboros to be like an installation progress bar that jumps by random increments. Sometimes it moves forward quickly, other times it taunts you by not making any real progress despite new blocks being produced.

This gives Ouroboros unpredictable latency like Bitcoin. In the best case 2/3+ of the stake might get scheduled in the a half dozen blocks, but in the average case it will take much longer, particularly if there are many producers with 1% weight or a producer with 50% weight is scheduled many times in a row by random chance.

Distribution Security Issues

I have previously made the case that BitShares, Steem, and EOS are the most decentralized because it has the most unique confirmations per confirmation window. In a 6 block confirmation window for Bitcoin only 5 unique individuals confirm a block on average (usually at least one mining pool goes twice in a random 6 block window). In Steem 14 people confirm a block each round.

Because stake and votes are distributed by pareto principle, we know that Ouroboros will assign block producers like mining assigns mining pools. It is exceedingly unlikely that 100 producers will each have 1% of the delegated stake. It is far more likely that there will be fewer than 20 individuals with more than 1% stake required to be approved. Furthermore, there are voting paradoxes in play where voting for someone who doesn’t already have 1% or more of the stake is a wasted vote.

In past articles on proof of stake I have also shown that even if Ouroboros removed the 1% requirement to participate, it would be economically unviable to cover the cost of operating a node with income from less than 1% of the block rewards. I have also argued in the past that because stake is distributed by pareto principle, and voter selection of candidates is also selected by pareto principle, the resulting distribution of stake among producers is pareto2. In other words, stake-weighted voting creates a very high centralization that can only be countered with approval voting followed by giving the top N equal weight (like BitShares, Steem, and EOS do).

Even if the stakeholders divide their stakes and votes to attempt to even out the producer weights, the system is still ultimately under pareto control 1% of the individuals control 51% of the stake. Corruption takes place at the individual level, not the stake level. Furthermore, it is wrong to assume that large stake holders will behave like a group of smaller stakeholders of similar size. Regardless of their stake, they only have one opinion and one interest and therefore the information (good or bad) they contribute to the system is independent of the size of their stake.

Conclusion

Cardano’s Ouroboros algorithm is not mathematically secure due to bad assumptions regarding the relationship between stake and individual-judgment being distributed by the pareto principle. Furthemore, their algorithm is not “new” but a less secure slower variation of the DPOS algorithm I originally introduced in April 2014. The authors of the paper failed to cite relevant prior art or to justify why their deviations from existing art are an improvement.

A blockchain consensus algorithm claiming to value peer review needs to consider who they consider their peers and all such reviews should be public. In the blockchain space, our peers are other blockchain technology companies. From this we can see that DPOS (and variations thereof) is one of the fastest growing consensus algorithms in terms of the number of unique projects choosing it.

I am going to go a step further and claim that much of the academic research and proofs performed by Cardano’s team only bolsters the support and justification of many core DPOS concepts, even if their approach is suboptimal compared to designs of EOS, BitShares, and Steem.