10,000 Years of Strangeness: A Paranormal Primer for Ancient and Modern China

Part II: True Tales from the Locals

Chapter 7: Alien Exam—外星人经过高考了 (Don’t think the pun translates)

Chapter 7: Alien Exam—外星人经过高考了 (Don’t think the pun translates)

Previous Chapters 前章: Pt. 1: Chapter 1, Ch 2, Ch 3, Ch 4, Ch 5-1, Ch 5-2, Ch 5-3, Ch. 6

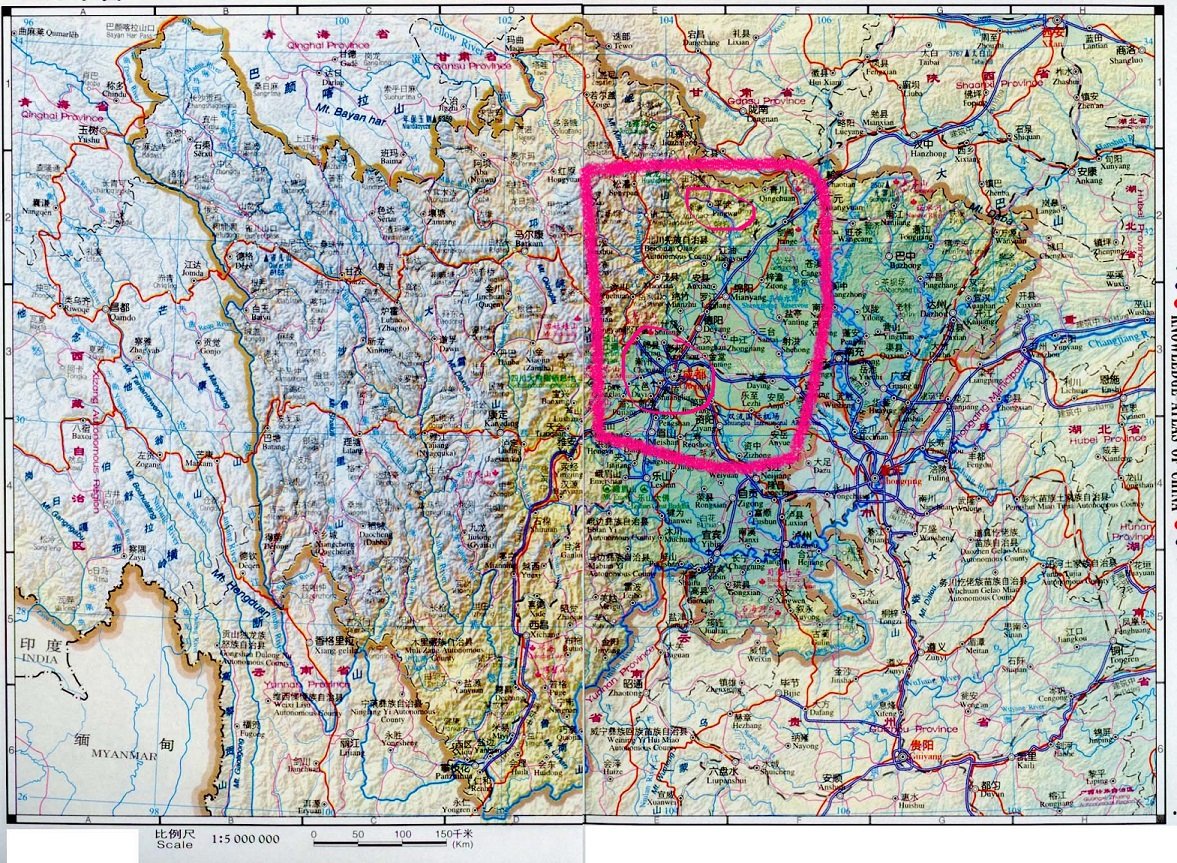

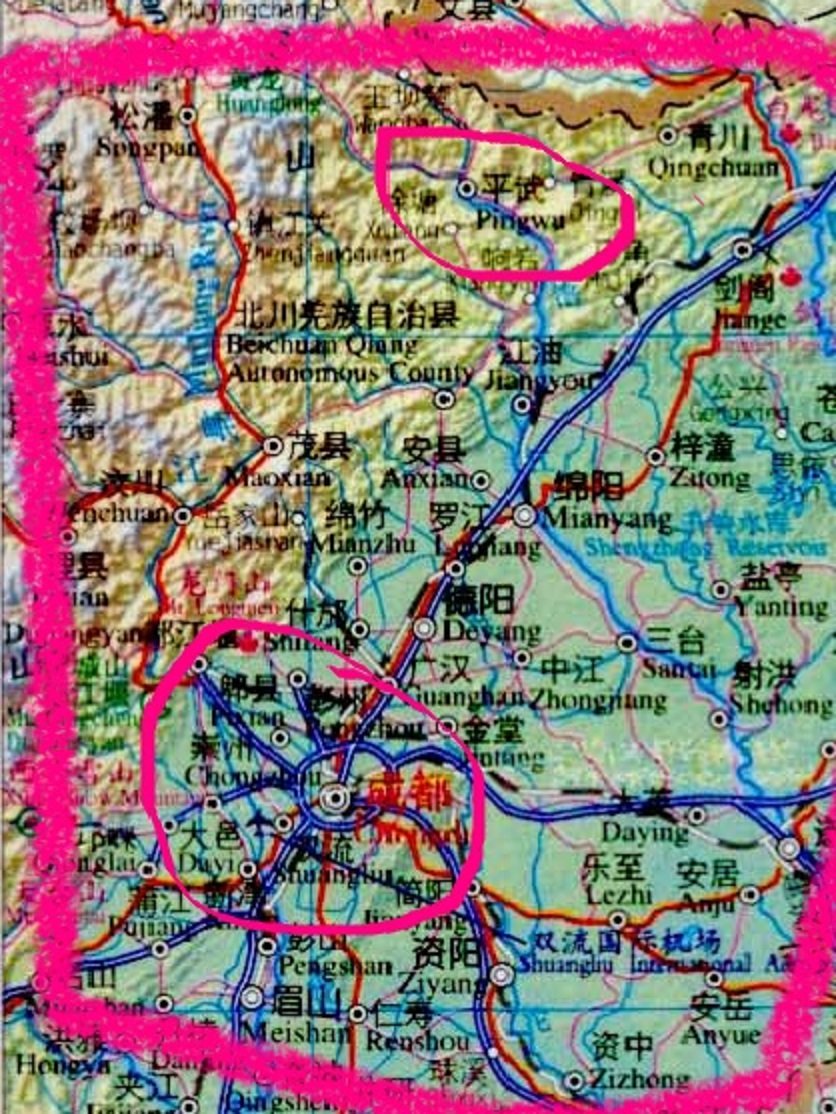

Pingwu (平武) is a remote county seat surrounded by peaks in the northern Sichuan wilderness in the heart of Panda country. It’s nestled in the Qionglai Mountains not far from the Wolong National Nature Reserve, home to the largest wild population of giant pandas, and Jiuzhaigou, one of China’s most popular and famous scenic spots. Despite its remoteness and small stature in size, its historical stature should not be underestimated.

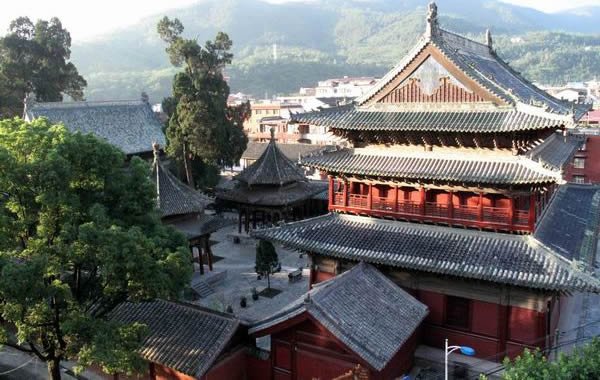

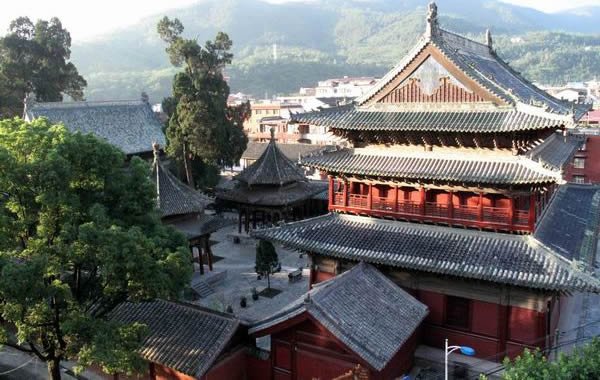

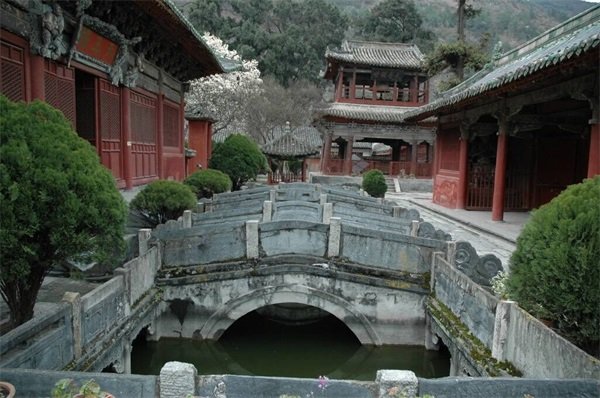

It is not only a stop-off on the way to Jiuzhaigou and Wolong. It is a tourist destination in its own right because it possesses one of the most magnificent Buddhist temples in China: Bao’en temple (报恩寺). Bao’en Temple goes back over 500 years to the Ming Dynasty.

An ambitious mid-15th Century local chieftain or Wang Xi (王玺, may be an imperial title, not a name), fancied himself to be an emperor. As a demonstration of his ambition, he built in Pingwu a replica of the real Emperor’s residence in Beijing, the Forbidden City ( 紫禁城), though somewhat smaller. Most of it was completed by 1443. One of Wang’s officials, knowing who ultimately controlled the butter his bread was buttered with, sent word to the Emperor in Beijing.

When word got back to Emperor Yingzong (英宗), also known as Zhu Qizhen (朱祁鎮), of what was going on, the Emperor decided he’d better investigate and dispatched an inspector to Pingwu to reconnoiter.

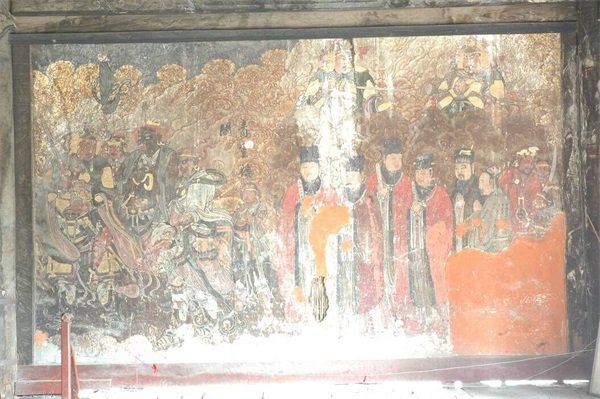

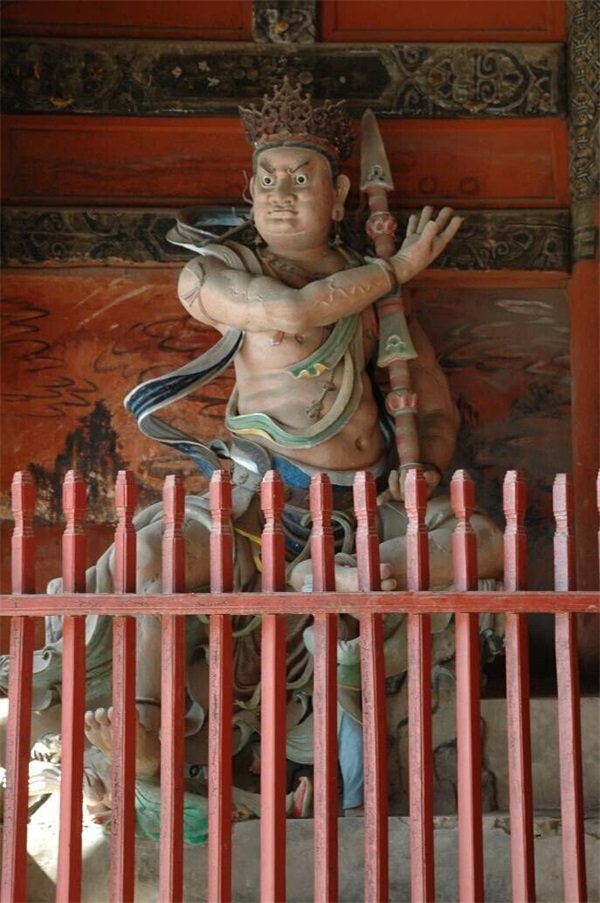

However, the wily Wang Xi was hip to the Emperor’s plan, or perhaps knew what to expect, and got a clever idea. He knew it would take months for the inspector to arrive, owing to the horrendous travel conditions of the day and the remoteness of his lair, and immediately got to work. He began creating magnificent works of Buddhist art and placing them all over the ‘palace’ complex. From skillfully carved reliefs and ornaments, to spectacular statues of Buddhist deities, he began filling the palace complex with religious figures and texts.

By the time the imperial inspector arrived, he did certainly see a replica of the Forbidden City, but it seemed to be more of a temple complex or a monastery than a palace. Wang Xi explained that it was indeed such a replica, but it was built as a temple to honor the Emperor, show his thanks to such a powerful and just ruler, and to bring blessings upon the imperial throne. It was called Bao’en Temple (报恩寺), which can be roughly translated as the Temple of Thanksgiving. The inspector was convinced and returned to Beijing. Wang Xi, having just had a close and monumentally expensive (get it?) brush with the very long arm of the law, maintained his new complex as a monastery. By 1460 he had finished adding the ornaments, wall paintings and detail that make the place famous today. In fact, it may well be his son who completed it as the Chinese sources attribute its construction to “王玺父子,” which may mean it was a father and son who shared the hereditary title Wang Xi.

The temple is built without using a single nail. It was built using dougong (斗拱), a kind of fitted joint that allows a tongue to move within a bracket that is characteristic of Chinese architecture. As a result, it is one of the oldest and best preserved temples in China. It survived over 500 years of earthquakes, including some of the most devastating ever to hit China, and even the world.

The infamous 1976 Songpan-Pingwu earthquake couldn’t take the temple down, nor could the even more devastating and utterly tragic Wenchuan earthquake of 2008 that wiped out whole villages along with their populations. The Wenchuan earthquake, known outside China as the Great Sichuan Earthquake, left over 69,000 people dead and another almost 20,000 missing. The quake measured a staggering 8.0 on the Richter scale and had effects in virtually every province of China. I, myself, had at least a dozen students in Shenzhen with affected family members back in Sichuan and remember donating blood for the victims at a Red Cross bloodmobile in the Taoyuan neighborhood of Shenzhen. Yet Bao’en Temple, just a few miles from the epicenter, remained standing.

Now we travel to July 24, 1981, in Pingwu, at the time my friend and former colleague Karen lived there. Pingwu was a city of about 10-20,000 people then by Karen’s estimate. Students were preparing for the Gao Kao (高考), a test given to all high school students in China. It is a grueling final exam-college entrance exam combination that may be the single most stressful event in a Chinese person’s life, aside from earthquakes. The test is at the end of the school year and every single frikking Chinese high school senior takes it on exactly the same day. It is not like the SAT where you choose what day to take it, and you can take it more than once and keep your best score. Nope. It’s not like that. They announce the date for the exam every year, and every damned student has to take it on that day come Hell or high water. Parents get just as worked up as the students do.

Karen was a senior in high school that year and about to take the Gao Kao, which is why she remembers this event so vividly. The temple was in a state of disrepair at that time, following the vandalism of the Cultural Revolution. What nature could not destroy in 500 years, the Red Guards endeavored to, with limited success. As she recalled, what they had done mainly was decapitate statues, but the buildings were more or less intact.

An interesting side note here is that as you travel around to ancient Buddhist and Taoist temples in China you often see signs that say something to the effect of “This building was destroyed by fire in 1965 but reconstructed in the 1980s.” Reading between the lines we gather that what Mao destroyed, Deng rebuilt. To the benefit of our world heritage I might add.

As the date of the Gao Kao approached, geologists in Japan were predicting an earthquake for that part of China. Japan itself is a nation rocked by devastating quakes, and, as you might imagine, geology is a valued profession there. Japan spends as much time scrutinizing the earth’s tectonics as the USGS does, if not more. Insights to the movements of the earth’s crust along with its effects can save millions of lives in earthquake prone areas. Constant monitoring along with building codes play an important role in the preservation of life. Accurate earthquake prediction is the Philosopher’s Stone (点金石). China, meanwhile, was just emerging from the isolation of the 1950s and Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and was short of geologists. Thus, when Japanese seismologists forecast an earthquake in a place like Sichuan, the locals didn’t laugh it off.

So it was that the school announced to their student body that should an earthquake strike on Gao Kao day, the Gao Kao would be given in the large courtyard at Bao’en Temple, the only place locally proven to be safe from earthquakes for over five centuries.

You might well ask, why not reschedule the test? Couldn’t young healthy bodies be useful in rescue and recovery operations immediately following the earthquake? Would the best plan really be to sit on the shaking earth trying to write test answers on vibrating desks and exam papers?

But this is how academics think. Even more so, Communist academics. You don’t have to leave America to see the rigidity and utter lack of lateral or creative thinking in academicians or their idolization of authoritarianism and self-adulation. In short, they are the biggest bunch of educated idiots and minions of evil no matter what country you’re in and deserve to be loathed.

Be that as it may, come July 24, the students and teachers were prepared, if necessary, to take their Gao Kao in the courtyard of the old temple. But it was not to be. The earthquake didn’t come to pass, and the students showed up on schedule to take the test at school. It is a grueling all-day affair. By the time it’s over in the early evening they are exhausted.

But for teenagers anywhere, with the relief of stress comes blowing off steam, and that is what they proceeded to do on the playground of the school, which can be seen the class photo below. This is the actual class that we are talking about in the actual square where the actual event I am about to tell you about actually took place on July 24, 1981.

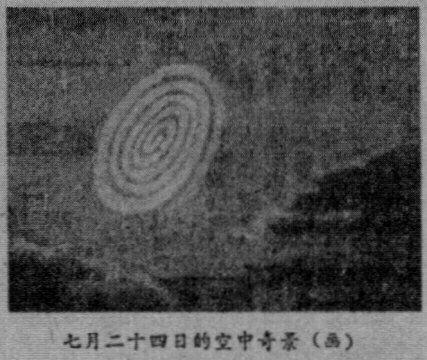

Around 8:00 p.m. while the students frolicked in the school square, a strange object appeared in the sky. Karen says that for her, the object was moving from left to right through the night sky, though she doesn’t remember which direction she was facing. It was a bright, glowing silver spiral suspended in the sky. The center of the spiral was at the top, forming a tip, while the rest of the spiral hung beneath it, unraveled like a hanging party decoration so that it formed a cone. The spiral moved slowly across the sky and disappeared from view as it crossed Laotuan Mountain (老团山), the tallest of the peaks that surround Pingwu.

It was witnessed by everyone present on the playground at that moment, and one of her former classmates has corroborated her story. It would be easy to blow this off as the imagination of exhausted but exuberant youth. They were fatigued. It was almost dark. They were seeing things.

The only problem with this mundane dismissal of the report, is that on July 24, 1981, the same object was reported in the night sky by millions of people in 15 provinces across China including Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi, Gansu, Guizhou, Yunnan, and Sichuan.

What had these millions of people witnessed? Was it really an extraterrestrial spacecraft? Was it a secret military experimental aircraft? Was it a rare aerial phenomenon? In the final chapter, we will see that such objects have a loooong history in China, and that it continues to this day.