The Symbiosis Project,

or The Future Belongs to Those Who Tell a Better Story

We live in a time on the cusp of socio-political revolution. Our leaders lie and cheat their way into power only to use that power for their own personal profit. As we continue to hear in the news some reach for violence as a solution. But, violent revolutions have always resulted in new plutocrats, not the abolition of plutocracy. I join with others in calling for a revolution of consciousness. But what does that even look like? This is the second in a series of articles that aims to answer that question.

This is a true story. It all starts one week from today.

Eat, Drink, and be Merry!

After reading about it online, a Portland man decided to start a community beer-brewing co-op. He found eight neighbors who were also interested. Together they bought $500 in equipment and supplies—enough to brew 30 gallons of beer. Over the weekend, they got in touch with every household in the three-block area around them. They ended up finding 45 people who were interested in brewing and/or drinking beer with them.

At $30 per month, members were only paying $1.88 per pint of beer, brewing lessons, and access to expensive brewing equipment. But, most importantly, it was a good excuse to get together with neighbors over drinks every week. Folks who couldn't attend got their growlers delivered to their doors.

Everyone being fairly strapped for cash, the members all paid the minimum $30 per month. Even so, the co-op raised $1350! To make their first 120 gallons, the co-op spent $400 on ingredients and $500 on equipment, leaving them a surplus of $450 and 30 gallons of beer. So, at the end of the month, they decided to throw a potluck block party and invited the neighborhood, regardless of co-op membership, to come discuss how they could best spend the extra money.

―❦―

A Sense of Community

By the third month, the co-op had raised $2,000 total and the entire neighbourhood had saved $1,000 on internet costs—giving the community as a whole $3,000 extra and plenty of beer. Another neighbour had had solar panels installed by Solar City the previous year. He told the group how they offered the panels for no money upfront because Solar City made their money by owning the panels and selling the electricity back to the grid. This scheme saved him an average of $10 per month on electricity over the past year. They also offered $400 for referrals, which he suggested be put back into the neighborhood. Photovoltaic panels don't work on all houses, but five did end up getting them installed. The community gained an extra $2,000 from these referrals.

After several months of sharing beer and cars—though not at the same time—the community became close enough to start discussing harder topics. At one dinner a woman admitted she had lost her job and was facing foreclosure. She never expected to be in this situation and the stress of not knowing what to do was taking its toll. After much discussion the community decided to work out an agreement to keep her house. They would collectively "rent" the house from her which covered her mortgage payment without requiring a deed transfer. In exchange, she would follow her passion and bake for the neighborhood. They also decided she could offer her house's spare bedroom as a bunk room for WWOOFers—people who live for free in exchange for doing community work, generally on organic farms.

One of the students was passionate about bikes and engineering and offered to build the community some hybrid electric tricycles from an open-source project he had been working on. These vehicles were electric assisted, able to carry groceries and other light cargo, met all legal bike standards, and were weather enclosed—meaning they could be comfortably ridden in the Portland rain. With the $3,000 surplus they had previously generated he was able to build four for anyone in the community to check out at any time. Also by this time, a few neighbors realized they worked very close to each other and started carpooling. Together with the GetAround program, now a few more folks could sell their vehicles without compromising their transportation needs.

―❦―

The Shape of Things to Come

With significantly fewer cars driving down the block, the neighbors noticed that they had much more space to meet and play during their monthly block parties. Another of the students, who was studying urban planning, proposed the idea of a Street Vacation Permit—a legal permit that allows the residents of a neighborhood to close off and collectively own their street in a trust.

The $5,000 permit was a bit of a gamble, but by now the community had more than that saved up and were willing to give it a shot. Application for a SVP takes a lot of work, but the student volunteers her time as it went toward her course credit. Two neighbors—a retired architect and a contractor—worked with the student to create a proposal.

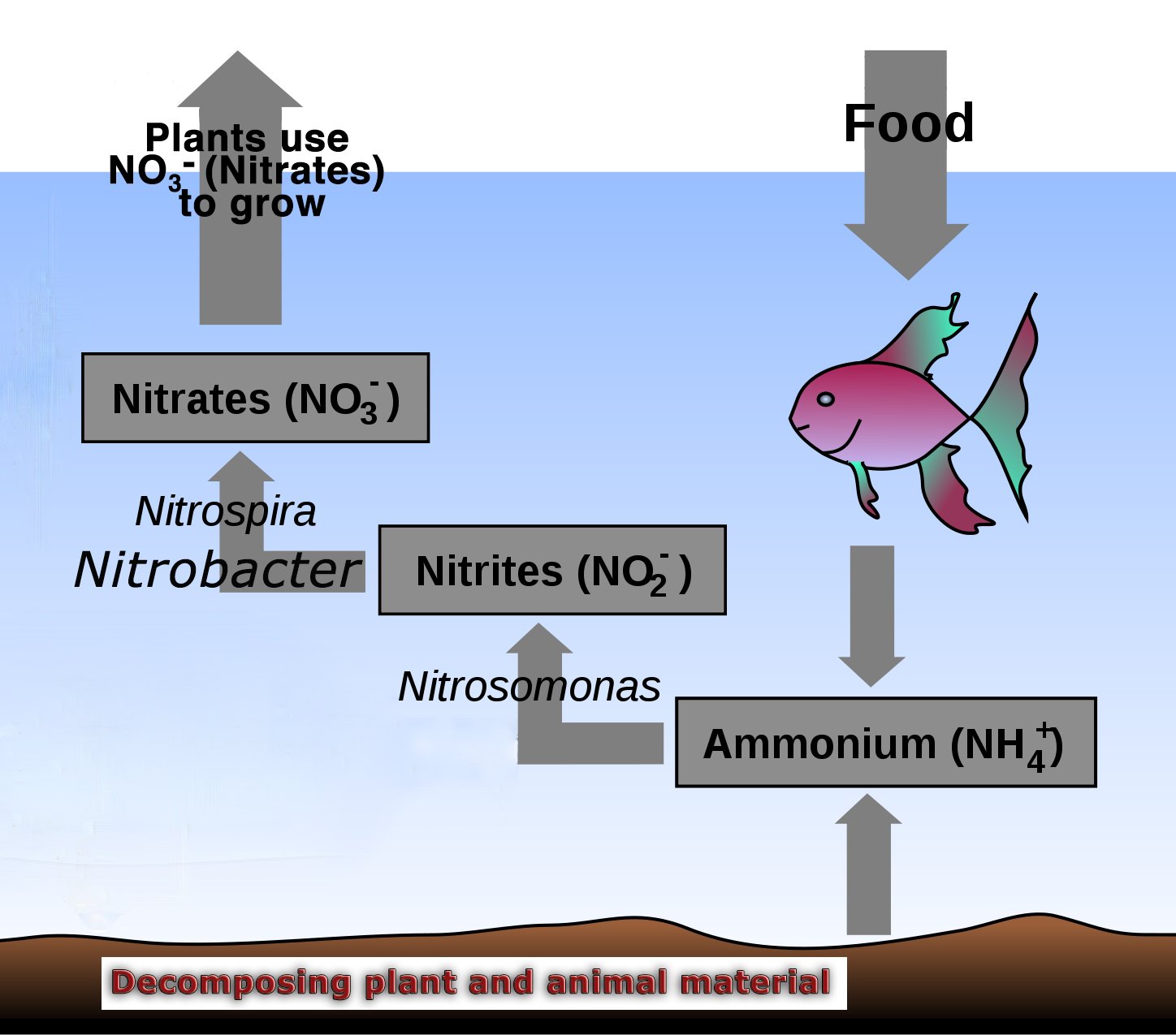

Aquaponics is a semi-closed system method of horticulture involving plants—like lettuce, bok choi, kale, basil, mint, & chives—fish—like tilapia, bluegill, crappie, catfish, or bass—pumped water, and bacteria—which convert ammonia & nitrite rich fish poo into nitrates that fertilize the plants. This system gives the neighborhood healthy, fresh greens and occasional, hyper-locally sourced fish meat. The edges of the grow beds were built to work as community benches where people could gather and chat.

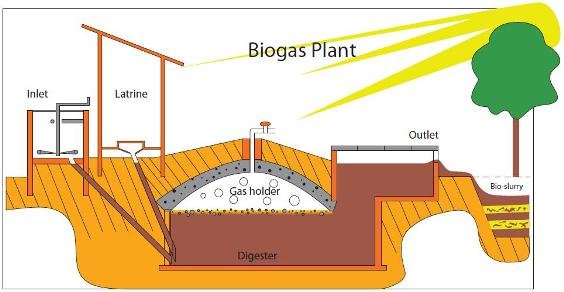

After having filed several block party permits, the Street Vacation Permit, a rainwater catchment permit, among others, the block had stayed on the radar of the city government. They even won a regional sustainability award. However, their next project went beyond what their local laws allowed—building a community biodigestion system. So, they worked with ReCode and the City of Portland to develop a new model of performance-based municipal code to replace the outdated technology-based code. This meant that as long as the system maintained agreed upon standards of safety and performance, it could be based on any technology. This expedited local innovation and adoption of new standards.

By the time the system was installed the neighborhood was already hosting a fresh batch of WWOOFers. One such student hit on a novel approach to heating and lighting the greenhouse during winter. A second hoop-style greenhouse was built over the original, with a 2' gap left between the two. The methane was piped through old glass lantern mantles. When burned, this provided white light, nearly-pure CO₂, and heat. This light helped extend the growing season for the plants. The captured CO₂ passed through heat-exchange pipes installed within the greenhouse. This heated the greenhouse while cooling the CO₂, which was finally dispersed through soapy water. This resulted in a CO₂-foam that filled the space between the greenhouses. The water & CO₂ absorbed and stored infrared light both from within and without the greenhouse. The white foam reflected back the gaslight. The net result of this experiment was cheap, artificial lighting & heat, which doubled as heat & light insulation, resulting in a more lush greenhouse, all while processing the community's solid waste into a useful fertilizer.

―❦―

Building a Better Future

Since the student interns already had to write up their work, from conception stage to final results, the community created a wiki to share their ideas, successes, and failures with the world. Soon, each community project—whether student-led, WWOOFer-led, or community-led—was being extensively documented on a wiki page.

A group in India made a novel design change in their system which lowered the amount of electricity needed to pump water. A group in Peru found that their bacteria culture produced more methane at similar temperatures. Each community connected through various internet platforms and made their data openly available to each other and each community benefitted from each other's tweaks.

There was a setback though, most of the Indian group's materials were documented in Bengali, while the Peruvian team had written everything in Spanish. Still, within two weeks all three projects were communicating with ease due to their use of an innovative platform called DuoLingo. It is an online language-learning tool that teaches language comprehension by giving students real-world text to translate. The communities crowd-sourced translations of each website & document. The students were provided with non-standard source material and the groups got free translations which they used to create mirrors of each other's work.

This worldwide network of independent communities had accidently created a kind of open-source academic journal where experiments were tried, replicated, and verified. They had incidentally recreated peer-review! And best of all it was free to access and unanchored to any for-profit university or journal system. Once the students had graduated and began looking for jobs, they discovered that having documented their work on the Internet, they could easily reference them as proof of mastery. The model of resumes and degrees started to become outdated. People began pursuing projects as a form of education and reputation building. More people began utilizing autodidactic communalism meaning fewer people needed to participate in the debt-based education system.

During one of these projects one of the neighborhood teens, who was interested in programming, realized that once the data points from several technologies were established and confirmed, it was possible to create a model the performance of their systems on a computer. He realized that the community's several aquaponics systems could be connected together into a single more efficient, chemically diverse system. This led him to realize he could use his maximization algorithms to take data from all across the wikis and find ways to fit each system together. He created plug-n-play systems that could be tailored to fit the human needs across a gamut of environments. His systems then went on to completely eliminate the concept of waste.

This led to a worldwide open-source innovation revolution, where the performance of all new micro-scale innovations were documented in a standardized format and added to a database. Through this database users could simulate performance of different combinations of techniques that would utilize the flows of energy they had in abundance—most commonly solar, hydrologic, aeolian, thermal, and aerobic & anaerobic decomposition. Many of the communities purchased and/or made a variety of open-sourced 3D printers that could print in metal, glass, ceramic, plastic, and graphene. Now specialized parts could be quickly fabricated, tested, improved upon, and shared. New parts spread globally very quickly and the pace of technological innovation quickened.

Such was the liberation of 9 billion thinking, dancing, loving, exploring, laughing, striving human beings. They spent their days exploring their connections with each other, the natural world, their own consciousness, and the things that sparked their passions. Thus ended the age of competition and began the next chapter in the never-ending story of the evolution of consciousness.

The preceding article is my recreation of the article The future belongs to those who tell a better story. It used to be hosted at http://www.thesymbiosisproject.org/2013/04/26/336/. Sam Smith, the original article's author, has given me permission to repost the article with attribution. He can be contacted by email at Sam@thesymbiosisproject・org or by phone at ⑦①⑨・③③⓪・⑤①④④.

Image attribution:

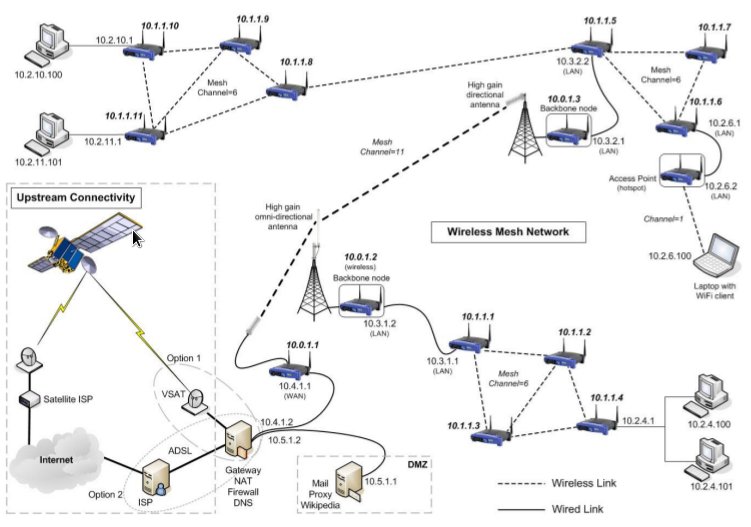

- Example wireless mesh network:

- This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license.

- Description: Diagram showing a possible configuration for a wireless mesh network, connected upstream via a VSAT link.

- Date: 25 January 2014, 10:50:59

- Source: Building a Rural Wireless Mesh Network: A do-it-yourself guide to planning and building a Freifunk based mesh network. Authors: David Johnson, Karel Matthee, Dare Sokoya, Lawrence Mboweni, Ajay Makan, and Henk Kotze (Wireless Africa, Meraka Institute, South Africa).

- Aquaponics diagram:

- This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

- Graphic courtesy of I. Karonent, adapted for aquaponics by S. Friend.

- Simple biogas plant diagram:

- I, the copyright holder of this work, release this work into the public domain. This applies worldwide. In some countries this may not be legally possible; if so: I grant anyone the right to use this work for any purpose, without any conditions, unless such conditions are required by law.

- All other images sustainably sourced from https://pixabay.com/.

If you enjoyed this article, please check out the first article in the series.