He was also in the field of medicine and a pharamicist.

H.H. Holmes

As reported in All That's Interesting,

Now and again, H.H. Holmes approaches a passerby, likely a young, attractive woman brought here by the gossip back home from someone who had already visited the White City or by a newspaper reporter who’d described its wonders.

With more than 27 million people flooding in from around the world to see the fair, Holmes has plenty of women to choose from. With practiced courtesy, he offers her a room at his hotel nearby. Flattered at this handsome stranger’s hospitality, she takes him up on the offer.

That night, as his newest victim settles into her rented room, her host scurries around in his secret passages and hallways, using every piece of the self-designed house for a macabre purpose.

From within a secret hiding place behind a wall, Holmes turns a gas valve and watches as the sealed, air-tight room containing his victim on the other side of the wall fills with deadly, suffocating gas.

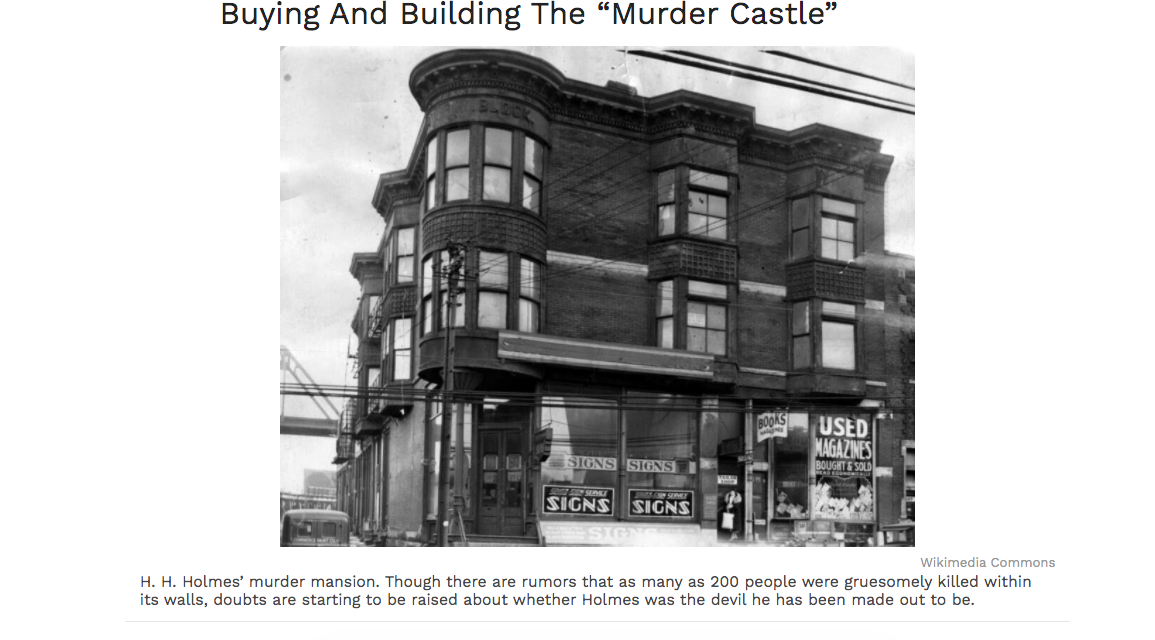

Before being brought to justice in November 1894, Holmes will have committed this gruesome act between two dozen and 200 times.

Or at least that’s how the story goes.

Whether it was insurance fraud, quack medicine, fake inventions, or elaborate schemes to hide cash from creditors, no con was beneath him so long as there was money in it.

He was a compulsive liar who rarely looked people in the eye, creating new names and backstories for himself to suit his purposes. Sometimes he was the son of an English Lord. Other times he had a wealthy uncle in Germany.

But what is mostly certain is that Holmes would kill nine people in a series of increasingly desperate tricks and manipulations in the first half of the 1890s. So, why do so many people believe the “real” body count to be anywhere between 25 and 200?

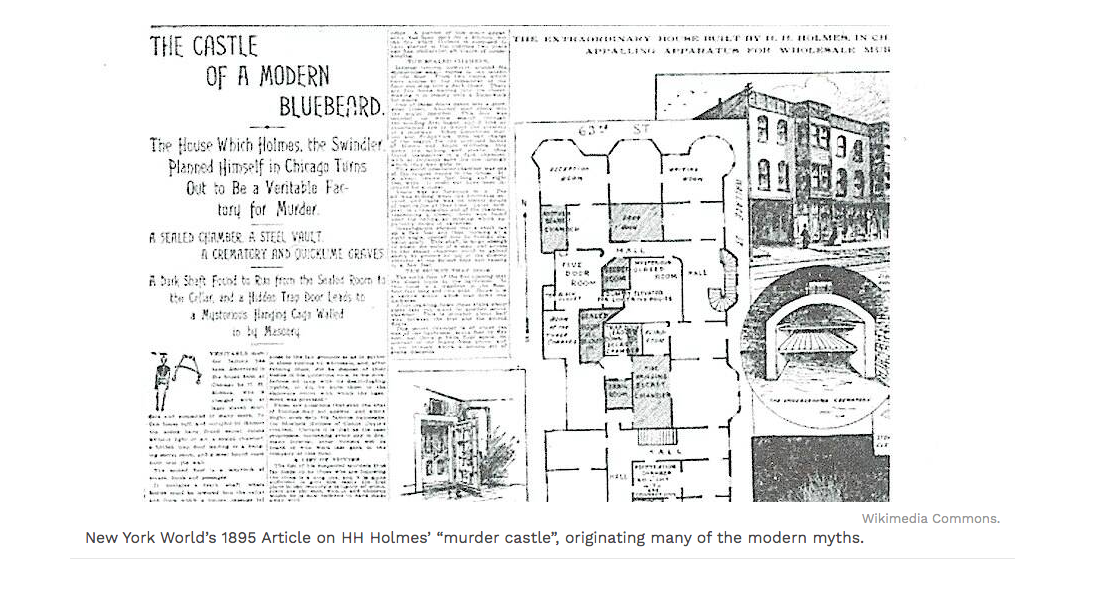

Dubbed a “modern Bluebeard” by William Randolph Hearst’s New York World, Holmes had become a nationwide sensation by the time of his November 1894 arrest and 1895 trial — the first for insurance fraud, the latter for murder. He was America’s answer to Jack the Ripper, whose grisly murders across the Atlantic had left readers spellbound seven years earlier.

In his 2017 book, H.H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil, author Adam Selzer attempted to answer these questions by studying newly digitized court records, police files, newspaper reports, and interviews previously unavailable to other authors.

Ultimately, the details and discrepancies he uncovered raise serious questions about how much “truth” there is to the traditional tale of H.H. Holmes.

After examining the evidence, H.H. Holmes may still have been a monster, just not the devil we think we know.

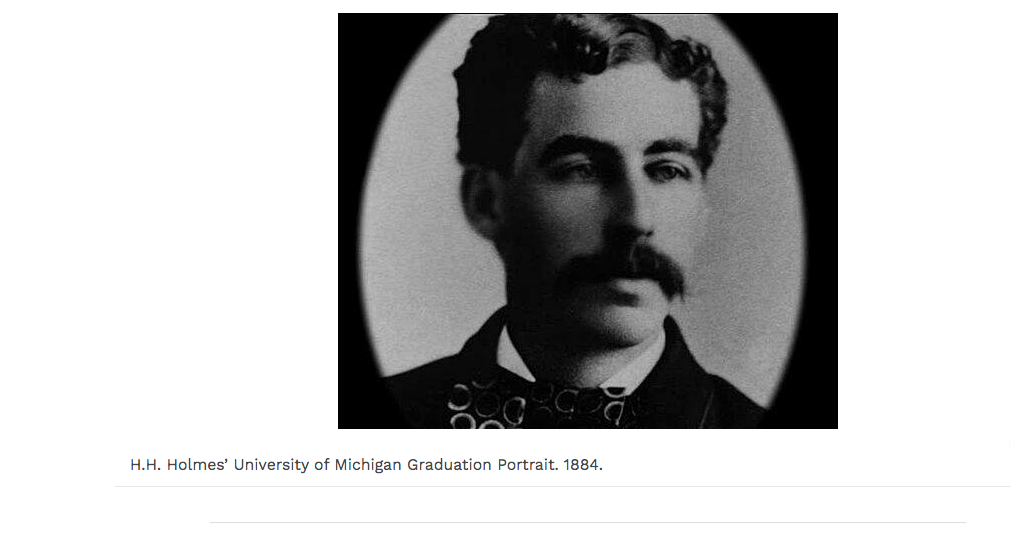

Herman Mudgett was born in Gilmanton, New Hampshire in 1861. Finishing school at age 16, Holmes became a teacher and soon set his sights on a local girl, Clara Lovering.

Though Holmes convinced her and her family to consent to marriage, the relationship soured almost as soon as she became pregnant.

At 19, Holmes then left New Hampshire to study medicine, abandoning Clara and their infant son, Robert.

After first enrolling at the University of Vermont, Holmes left for the University of Michigan either to move farther away from his family or because of the latter curriculum’s cutting-edge emphasis on human dissection (accounts vary).

Rumors and anecdotes from those who knew him at this time repeatedly mention his habit of stealing medical cadavers, both intact and in pieces.

In one story told by his Burlington landlady, she “noticed a foul stench in Holmes’s room emanating from a ‘dark object’ under the bed. Using the broom, she swept the object out and found that it was a dead baby.”

But according to his Michigan classmates, Holmes was quiet, serious, and somber. He didn’t talk much and, though he was a bit strange, he appeared mostly harmless.

Apart from stealing the occasional corpse or foot, most people remembered that he was training to be a missionary in Zululand — a lie — and a few others vaguely recalled an incident with a local widow.

In his last year of medical school, Holmes was sued for “breach of promise,” quite a serious crime at the time. His accuser claimed that Holmes proposed to her and consummated their “relationship” only to have her later find out that he was already married.

If true, the charges could have prevented him from graduating.

When the case became public, many who knew Holmes in the faculty and student body felt this was out of character for him, including one Professor Herdman, who helped successfully defend him against expulsion in front of the school board.

Later, after his graduation ceremony, Holmes told Herdman that the widow had been telling the truth.

That moment, the professor later wrote, “was the first positive evidence I had received up until that time that the fellow was a scoundrel, and I told him so at that time.”

It was only later that Herdman realized that Holmes had also attempted to burglarize his house on two separate occasions.

The Early Criminal Career Of A Promising Young Doctor

Depending upon who you ask, Holmes’ more fatal games may have started in medical school.

In his 1895 autobiography, Holmes’ Own Story, Holmes claimed he and a Canadian classmate had plotted to steal cadavers from their laboratory and pass them off as other people to collect insurance money.

The plan, in Holmes’ retelling, centered around a certain local family — a man, a woman, and their young daughter — all of whom had been convinced to take out a life insurance policy. After the family had been convinced to leave town, Holmes and his accomplice would present three mutilated bodies of about the right ages and appearance, collect the money, and split the profits.

They also agreed to split the work. Somehow in the middle of a national cadaver shortage, Holmes claimed to have found a body in Chicago, but his partner never followed through.

He stored the corpse in a barrel where it remained until he moved to Chicago in 1886. By that time, it was so rotten that the only thing to do was bury it in his basement.

At least, that’s what he said when the police later found the human bones inside his house.

Following graduation, Holmes – still Herman Mudgett — set up in Mooers Forks, New York working two jobs as a doctor and schoolteacher. Though there are refuted reports of Holmes showing his students a severed foot or marrying a woman who then went missing, one perhaps-true incident from this period is particularly striking.

A Civil War veteran came into the office that Holmes shared with another doctor named Steele. He was near death from what he claimed was an old war wound and asked that the physicians perform an autopsy to eventually confirm this in order to secure a military pension for his wife.

Holmes enthusiastically agreed.

When the man died, Holmes successfully located the bullet that had been lodged in his chest for more than 20 years. He then removed the bullet, along with the dead man’s shattered ribs, and refused to hand them over unless Steele paid him for them.

Steele, who already had enough evidence to confirm the nature of the injury and cause of death, refused. As far as Steele knew, Holmes kept the ribs.

It’s possible Steele had his own reasons for telling this story. In their last interaction, Holmes asked to borrow money for a train ticket to Chicago.

He never returned to pay back the debt, but he did leave other things behind. One was a box containing all mementos leftover from his life up to that point. The other was the name Herman Mudgett.

Find more on buying and building the murder castle here,

https://allthatsinteresting.com/hh-holmes

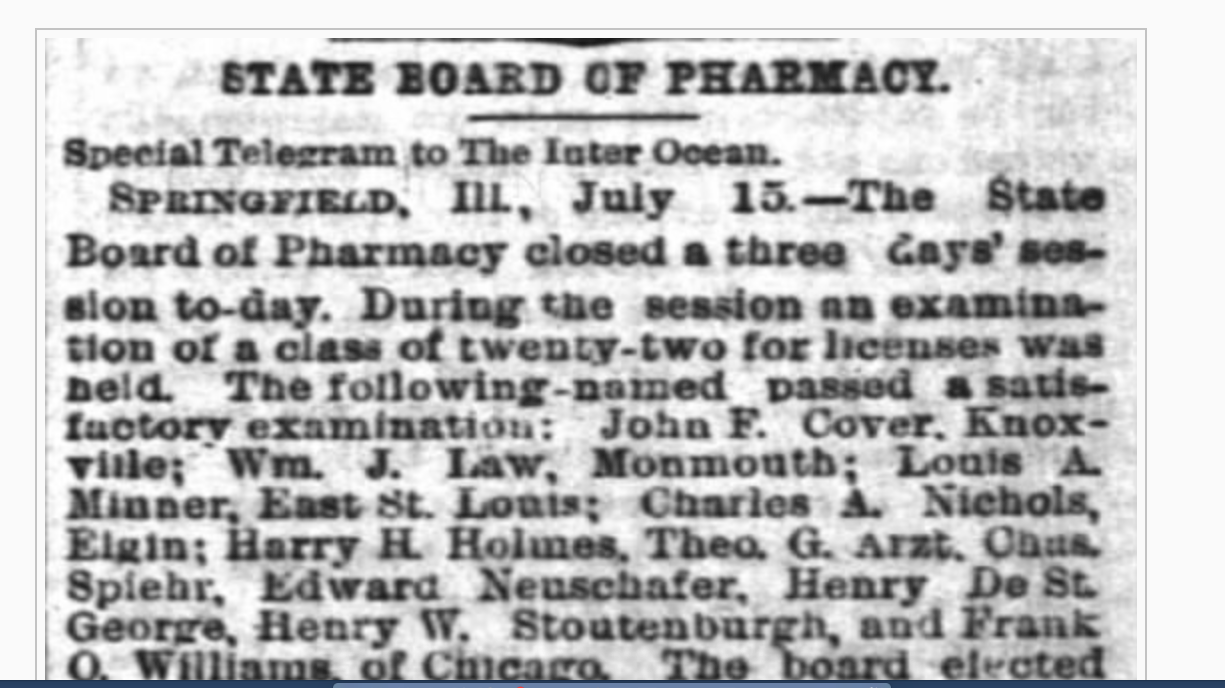

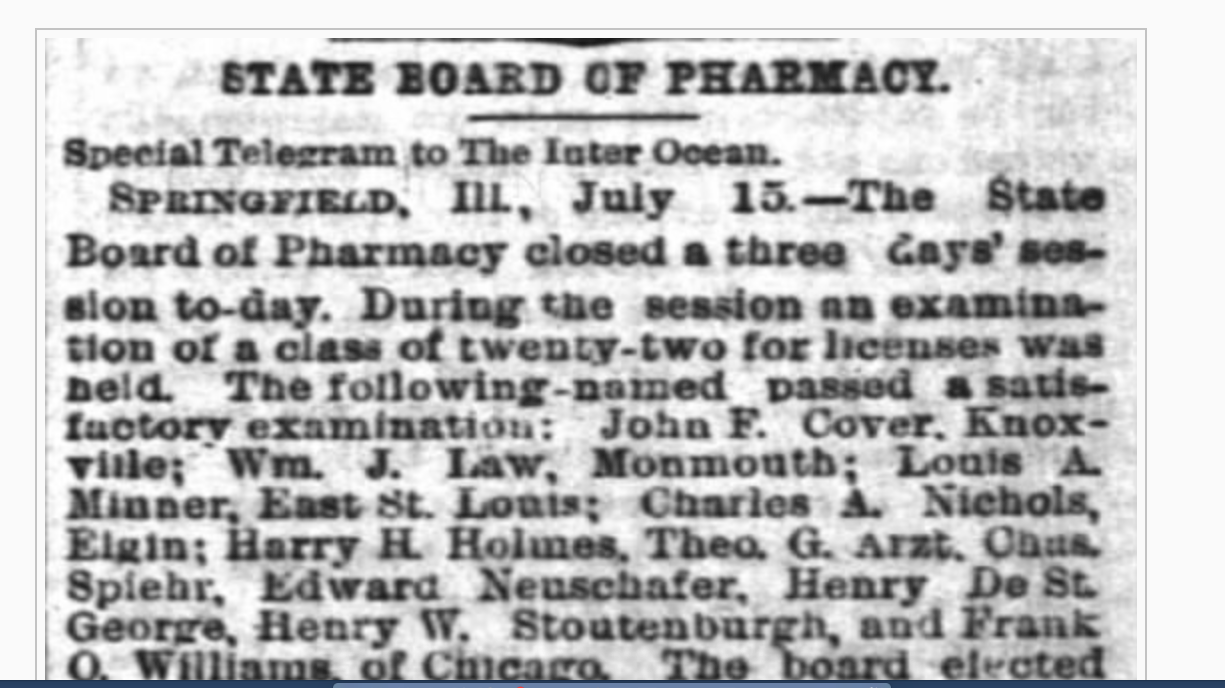

The name H.H. Holmes appears in Illinois newspapers and legal documents as early as 1886, when the new arrival took — and passed — a government test to practice pharmacy in the state.

After arriving in Chicago in 1886, Holmes visited Dr. E.S. Holton’s pharmacy on 63rd and Wallace in Englewood. In Larson’s Devil in the White City, the scene is sketched in vivid detail.

The elderly Dr. Holton lays on his death bed upstairs as Mrs. Holton eagerly sells the building to the young, handsome doctor, even though he cannot pay all at once.

Shortly after the building was rechristened under Holmes’ name, neighbors ask what happened to Mrs. Holton, who had apparently gone missing.

Holmes tells them she moved to California, but Larson, as well as other authors, strongly imply that he killed her and possibly Dr. Holton as well. But, what only Selzer seems to have noticed is that Dr. E.S. Holton was not an old man. She was a young woman.

Dr. Elizabeth Sarah Holton was pregnant at the time of Holmes’ arrival and apparently jumped at the chance to get off her feet.

By the time reporters and investigators were interested in Holmes and his infamous building, if the former owners were thought of at all, they were assumed to be other victims. In actuality, Dr. and Mr. Holton were alive and well a few blocks away.

After acquiring the two-story building, Holmes began a series of renovations. The most notable for those already familiar with the story are probably the so-called secret passages, false walls, dummy elevator shaft, trap doors, basement crematorium, and, eventually, a third floor outfitted with rooms to house World’s Fair attendees.

During his time at 63rd and Wallace, Holmes ran a variety of strange businesses and “get rich quick schemes” out of the building: quack cures for alcoholism, a copy machine company, and a glass-bending studio to supply Chicago’s new skyscraper boom utilizing converted furnaces as kilns.

Due to the skyscraper boom and Burnhams involvement it is very feasible he would have known Holmes. Like Burnham, Holmes was the architect when designing his castle.

But, even if the central part of Holmes’ story involving his running of a hotel during the fair is inaccurate, the doctor was still a devil in his own right.

Not long after arriving in Chicago, Holmes met Myrta Belknap of Minneapolis while she was in the city on business. Following a quick courtship, he convinced her parents to let them marry, sweetening the deal by buying them a house.

Holmes, briefly reverting to Herman Mudgett, filed for divorce against Clara Lovering, claiming she had committed adultery. And while Holmes did marry Belknap, he did not see his divorce through to its conclusion.

It is unclear whether or not Belknap and Holmes married legally or simply had a religious ceremony, but before 1890, the couple was living together in Wilmette with their new daughter, Lucy.

Just as with Lovering, however, whatever affection Holmes may have had for his new wife faltered soon after his daughter’s birth. He took up residence at his office and his visits back to Wilmette became rarer and rarer.

This is when the Conners arrived. Ned Conner, a jeweler, his wife, Julia, and their daughter, Pearl, took up residence at Holmes’ Wallace Street building in 1890.

Offered a chance to buy the building, Conner excitedly agreed, only to discover it came with certain strings attached.

For one, Holmes neglected to tell him how much debt the store was in, debt Ned Conners now owned along with the location. Second, his marriage with Julia quickly fell apart with a surge of fighting leading to divorce, which was still uncommon at the time.

In addition to his habit of defrauding creditors, inventing aliases, generally figuring out how to commit every kind of fraud, and committing bigamy, H.H. Holmes was indeed a murderer.

The name H.H. Holmes appears in Illinois newspapers and legal documents as early as 1886, when the new arrival took — and passed — a government test to practice pharmacy in the state.

According to Mysterious Chicago you can find,

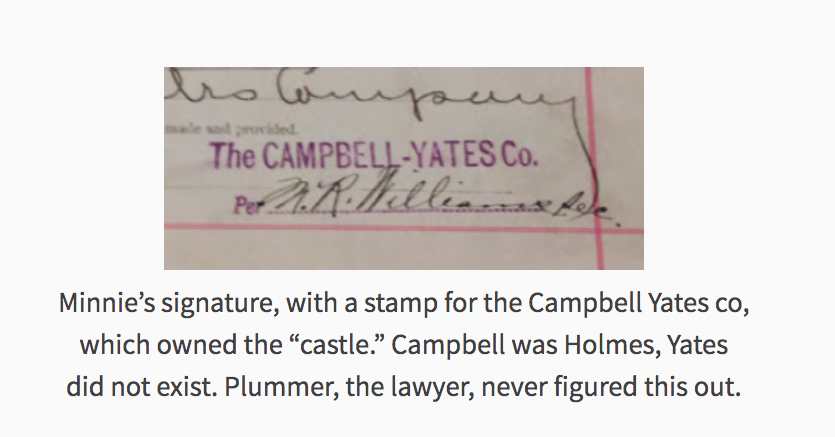

Lately I’ve been in and out of the archives, digging up lawsuits Holmes was in. The man got sued a lot, usually for buying goods and not paying for them. Yesterday I found a suit between him and H.W. Darrow, a man who somehow kept his name out of the papers, but was sued for supposedly-unlawful possession of one of the stores in the “murder castle,” as well as the room above it. The paperwork included the signature of Minnie Williams, who was Holmes’ secretary at the time (and probably his lover) (though she’s now one of his ten or so generally-agreed-upon victims, as well). It was a cool find, if only because the Feb 1893 date on the paperwork firmly established that Minnie was in Chicago before Spring of 1893, which is when some investigators thought she’d first arrived, which lends a bit more credence to her living in Lincoln Park in January, 1893.

Interesting. . .so yet Another Lincoln Park!

Back to Mysterious Chicago,

Now and then there’s some interesting info buried in the legalese of the lawsuit records, though; perhaps even a mystery, a story, or, at the very least, a new address to add to my “Where Was HH Holmes” map. You get just about all of those in the case of The Stock Yards Lumber, Coal, and Feed Company vs HH Holmes.

In March of 1893, less than two weeks before the Tobey Furniture company found that Holmes was hiding a bunch of their stuff in the hidden rooms of the “castle,” Holmes went to the lumber company (which was located near 47th and Halsted) and bought about 20,000 feet of lumber on credit – roughly 500 bucks worth – including a couple thousand feet of flooring, and a couple thousand feet of ceiling.

The “Castle” being pretty well built by then, it’s anyone’s guess what he was using it all for. It was around this time that he started planning a building in Fort Worth, but he wouldn’t have used Chicago lumber for that.

He may have planned to get it, not pay for it, and then sell it at a 100% profit, or he may have planned to burn it up for the insurance money. In any case, he never paid for it and managed to keep it from being repossessed, so the company sued.

Paperwork in the suit is dated as late as October, 1895, when Holmes was in prison. A news item from October, 1896, indicates that the case was still going on then, even though Holmes had been dead for nearly six months. When the case came back up, the company’s lawyer asked for the case to be dismissed, though he told the court, “I don’t know, personally, that the defendant is dead.

All the information I have obtained was from the newspapers, which told us that he was hanged in Philadelphia.” The judge said “I think we can assume with safety that he is dead” and threw the case out.

Interesting. . .Lots and lots of Fires in Chicago around this time period as they also Cleared out the World's Fair Buildings there and the secrets that they held.

A few months later, the Stock Yards Lumber Company was badly damaged by a fire, and doesn’t really appear much in any records or books much after that. Perhaps we can add them to the list of possible victims of the “Holmes Curse,” which we analyzed in a recent ebook at the left.

Some other suits I’ve dug through include a suit with Dr. MB Lawrence, who lived in the castle and loaned Holmes a few thousand bucks to convert it into a hotel (some documents from that are in our expanded Murder Castle ebook), one with Morrison and Plummer (wholesale drugs), The James Cycle Co (which is still in business), a bedding company, the Tobey Furniture Company, the Illinois Vault Co, a cigar company, and a handful of individuals who had the misfortune to loan the guy money.

Back to the Connors story

Once again,

This is when the Conners arrived. Ned Conner, a jeweler, his wife, Julia, and their daughter, Pearl, took up residence at Holmes’ Wallace Street building in 1890.

Offered a chance to buy the building, Conner excitedly agreed, only to discover it came with certain strings attached.

For one, Holmes neglected to tell him how much debt the store was in, debt Ned Conners now owned along with the location. Second, his marriage with Julia quickly fell apart with a surge of fighting leading to divorce, which was still uncommon at the time.

When he realized that Holmes and Julia were sleeping together, he began to wonder whether Holmes had implicitly offered him a trade: the store for his wife.

Ned moved out and sold Holmes the store back relatively quickly. What exactly Julia thought of all this remains uncertain.

In addition to the loans and business holdings he kept under his own name, his various aliases, Belknap’s name, and Belknap’s mother’s name, Holmes had now added Julia to his list of “responsible parties.”

But some time after that, Julia and Pearl, common sights around the Wallace Street building, suddenly disappeared. Holmes said they had gone to visit family, but they were never seen again.

The Missing Miss Cigrand

Emeline Cigrand was next. A beautiful young secretary and typist at a rival alcoholism clinic, Cigrand likely met Holmes through his frequent accomplice and “business partner” Ben Pitezel, whom Holmes had sent for treatment at the center.

However he learned of her, Holmes soon offered her double her current salary to work with him. When exactly their relationship turned intimate is unclear. It was technically a secret, but several residents of the house had their suspicions.

Shortly before Christmas 1892, Mrs. Lawrence, another of Holmes’ tenants, had her last encounter with Cigrand.

The younger woman offered her an early present and spoke in vague terms about the future, leading her neighbor to ask if she was leaving her job and possibly Chicago. Cigrand said “maybe” — and seemingly vanished after that.

A concerned Mrs. Lawrence then asked Holmes what he knew about her whereabouts. Ms. Cigrand, Holmes said, had married her fiancé Robert Phelps — whom no one had ever met or heard of before — and had left the city on her honeymoon, quite possibly to never return.

He produced a wedding card from his pocket, suspiciously typewritten instead of in the more traditional printed fashion, and Mrs. Lawrence felt uneasy. Surely, she thought, Cigrand would have told her about such a serious romance or said goodbye before leaving.

Apparently, Holmes did not like that answer. However, he did not kill Mrs. Lawrence. Instead, a few days later he returned with a newspaper clipping reporting the wedding of Emeline Cigrand to one Robert Phelps.

It began:

“The bride, after completing her education, was employed as a stenographer in the County Recorder’s office. From here she went to Dwight, and there from Chicago, where she met her fate.”

Although at the time no one suspected Holmes in Cigrand’s disappearance or of having written the newspaper announcement himself, in hindsight, it seemed — and seems — the most likely explanation.

In addition to noting the dual meaning of “met her fate,” Mrs. Lawrence later testified that sometime after Cigrand’s disappearance she witnessed Holmes, Pitezel, and another associate named Patrick Quinlan moving a heavy trunk from the third floor out of the building.

By that point, she was almost certain it contained the body of Emeline Cigrand.

The Williams sisters came after that. H.H. Holmes met Minnie Williams on business in Boston sometime in the 1880s and saw two things he liked. Already a wealthy orphan, Minnie Williams could expect to inherit another small fortune after the death of her elderly guardian. Furthermore, Williams, often described as “plain,” could be flattered and manipulated easily.

Using the name Howard Gordon, Holmes swept Williams off her feet, gaining such control over her and her finances that she signed away several of her real estate holdings to him and moved to Chicago in 1893.

To limit complications, “Howard” explained that for “business reasons,” people called him H.H. Holmes in Illinois. Like many before and after her, for some reason, she believed him. The two “married” soon after her arrival.

No record of this marriage — Holmes’ third — is listed in the Cook County archives. While it could have been lost, it’s likely that Holmes simply arranged a sham ceremony.

After their father’s death, different relatives raised Minnie Williams and her sister Nannie, who was sometimes incorrectly called “Anna,” a name she never went by in life. Minnie grew up in Boston while Nannie lived in Alabama. The two maintained a correspondence, but once Minnie’s letters mentioned her recent marriage to a handsome, rich, and charming doctor, they arranged for a reunion in Chicago.

In one of the few known instances where Holmes went to the World’s Fair, he treated the sisters to a day’s visit in celebration of his sister-in-law’s arrival.

Nannie was skeptical of “Howard” at first, finding him much less attractive than Minnie had described, but the more time she spent in his company, the more she understood why her sister wanted to stay with him.

As far as we know, neither of them ever left.

A Second Southwestern Castle?

Nannie disappeared first. That much is certain. Then Holmes traveled to Fort Worth, Texas with Minnie in tow to take possession of some land she held there leftover from her family’s estate.

Ben Pitezel joined them, assisting Holmes in the construction of a new building, modeled to be an identical duplicate of the Chicago drugstore, “secret passages” and all.

Holmes’ scheme here is unclear. While it’s tempting to say that he wanted to build a second “murder hotel,” this theory has a few problems.

In addition to the likelihood that it was not a functional hotel, Holmes’ building in Chicago may not have had secret passages at all. These features could easily have been storage spaces to hide excess stock and a “hidden” back staircase to allow employees to travel between the floors unseen.

Some employees, by the recollection of Ned Conner, occasionally even slept in the so-called hidden chambers. Considering Conner was then openly wondering whether Holmes had killed his ex-wife and daughter, this testimony in Holmes’ “defense” should have considerable weight. If he said there were no secret passages, there’s reason to believe that there were, in fact, no secret passages.

It’s also worth noting that during the time Holmes was supposed to be busy luring fairgoers to their deaths, he was several states away.

Borrowing from multiple banks and commissioning work with IOUs, Holmes amassed a great deal of laundered money while distracting his creditors with the progress on the building. Once the structure was finished, he left Texas.

It appears Minnie Williams, however, did not.

Several witnesses later testified to seeing Minnie Williams after this period. However, almost none of them knew her, and Holmes’ later admitted to paying Patrick Quinlan’s wife to impersonate the missing woman. Minnie and Nannie Williams’ bodies were never found.

After his release, in January 1894, Holmes met and extralegally married his fourth and final wife, Georgiana Yoke, while using the name “Mr. HM Howard.”

This time, Holmes explained that his wealthy uncle had left him a great deal of land in his will on the condition that he adopt the dead man’s name. Yoke apparently had no problem believing this, but she also had no way of knowing that Holmes’ land had been inherited from Minnie Williams.

Meanwhile, Ben Pitezel, his wife Carrie, and their children Dessie, Howard, Nelly, Alice, and Wharton had moved to St. Louis, Missouri. In 1894, Holmes contacted Pitezel asking him to purchase life insurance so they could fake his death with a medical cadaver. Pitezel agreed and the pair traveled to Philadelphia, but not before explaining the plan to Carrie.

According to this source. ..

https://joshuashawnmichaelhehe.medium.com/h-h-holmes-576dde2ac91c

While he was enrolled in medical school, Mudgett worked in the anatomy lab under Professor Herdman, the chief anatomist. Herman Mudgett also apprenticed in New Hampshire under Dr. Nahum Wight, a noted advocate of human dissection. All of this gave him extensive knowledge of the inner-workings of the human body. The was that Mudgett developed a morbid fascination with cadavers, and he took extreme delight in the uncanny aspects of dissection. The school’s janitor even introduced Mudgett to black-market corpse trafficking. So, he learned to think of corpses as commodities at a time when medical cadavers were frightfully scarce.

That’s when Herman Mudgett started robbing graves to pay his tuition up until he graduated in 1884. Thus, he went from being a horse-thief in New England to a body-snatcher in the Midwest all in the course of becoming a doctor. Mudgett then moved to Mooers Forks, New York, but not long after that, a rumor began to spread that he had been seen with a little boy who later disappeared. When he was confronted about it. Mudgett claimed that the boy went back to his home in Massachusetts. Although no investigation took place, Mudgett quickly left town anyway.

As reported by Murderpedia,

Holmes trapped, tortured, and murdered possibly hundreds of guests at his Chicago hotel, which he opened for the 1893 World's Fair.

The case was notorious in its time, and received wide publicity via a series of articles in William Randolph Hearst's newspapers. Interest in Holmes' crimes was revived in 2003 by the publication of a best-selling book about him, The Devil in the White City.

Although Holmes is sometimes referred to as America's first serial killer, his crimes occurred after those of others such as Thomas Neill Cream, the Austin Axe Murderer and the Bloody Benders

He managed to secure a Chicago pharmacy by defrauding the pharmacist, and built a block-long, three-story building on the lot across the street. He called this building "The Castle," and opened it as a hotel for the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893.

The bottom floor of the Castle contained shops, the top his personal office, and the middle floor a maze of over one hundred windowless rooms. Over a period of three years, Holmes selected female victims from among his hotel's guests, and tortured them in soundproof and escapeproof chambers fitted with gas lines that permitted Mudgett to asphyxiate the women at any time.

Holmes had repeatedly changed builders, to ensure that no one truly understood the design of the house he had created who might report it to the police. Once dead, the victims' bodies went by chute to the basement, where they were either sold to medical schools or cremated and placed in lime pits for destruction.

From this source children were also involved

Following the World's Fair, Holmes left Chicago and apparently murdered people as he traveled around the country. He was arrested in 1895 when he was discovered with the body of a former business associate, Benjamin Pitezel, and three of his children.

The same year, Holmes's "castle" in Chicago burnt down on August 19, revealing the carnage therein to the police and firemen. His habit of taking out insurance policies on some of his victims before killing them may have eventually exposed him regardless. The number of Holmes' victims has typically been estimated between 20 to 100, and even as high as 200. These victims were primarily women, but included some men and children.

Holmes was put on trial for murder, and confessed to 27 murders (in Chicago, Indianapolis and Toronto) and six attempted murders. He was hanged on May 7, 1896, in Philadelphia. It was reported that when the executioner had finished all the preliminaries of the hanging, he asked, "Ready, Dr. Holmes?", to which Holmes said, "Yes. Don't bungle." The executioner did "bungle," however, because Holmes' neck did not snap immediately; he instead died slowly and painfully of strangulation over the course of about 15 minutes.

Mudgett was born in Gilmanton, New Hampshire. He was the son of Levi Horton Mudgett and Theodate Page Price. The family was descended from among the first settlers to the area. He grew up with a father who was a strict disciplinarian, and he was often bullied as a child. He claimed that, as a child, he had been forced by other students to view and touch a human skeleton after they found out about his fear of the local doctor's office. The bullies had initially brought him there to scare him, but instead he was utterly fascinated.

While in Chicago, Holmes came across Dr. E.S. Holton's drugstore. It was located at the corner of Wallace and 63rd Street, in the neighborhood of Englewood. Holton was suffering from cancer while his wife minded the store. Through his charm, Holmes got a job there and then manipulated her into letting him purchase the store. The agreement was that she could still live in the upstairs apartment even after Holton died. Once Holton died, Holmes murdered Mrs. Holton and told people she was visiting relatives in California. As people started asking questions as to when she would be coming back, he elaborated the lie and told them she loved it so much in California that she decided to live there.

Holmes purchased a lot across from the drugstore, where he built his three-story, block-long "Castle"—as it was dubbed by those in the neighborhood. It was opened as a hotel for the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893, with part of the structure used as commercial space.

The ground floor of the Castle contained, aside from Holmes' own relocated drugstore, various shops (a jeweler, for example), while the upper two floors contained his personal office as well as a maze of over one hundred windowless rooms with doorways that would open to brick walls, oddly angled hallways, stairways to nowhere, doors that could only be opened from the outside, and a host of other strange and labyrinthine constructions.

After Chicago

A.K.A.: "Dr. H. H. Holmes"

Classification: Serial killer

Characteristics: To collect insurance money - Torture

Number of victims: 27 +

Date of murders: 1886 - 1894

Date of arrest: November 17, 1894

Date of birth: May 16, 1861

Victims profile: Men, women and children

Method of murder: Several

Location: Indiana/Pennsylvania/Illinois, USA - Canada

Status: Executed by hanging at Moyamensing Prison, Philadelphia, on May 7, 1896

Herman Webster Mudgett (May 16, 1861 – May 7, 1896), better known under the alias of "Dr. H. H. Holmes," was an American serial killer.

Holmes trapped, tortured, and murdered possibly hundreds of guests at his Chicago hotel, which he opened for the 1893 World's Fair.

The case was notorious in its time, and received wide publicity via a series of articles in William Randolph Hearst's newspapers. Interest in Holmes' crimes was revived in 2003 by the publication of a best-selling book about him, The Devil in the White City.

Although Holmes is sometimes referred to as America's first serial killer, his crimes occurred after those of others such as Thomas Neill Cream, the Austin Axe Murderer and the Bloody Benders

Biography

He was born in Gilmanton, New Hampshire, son of Levi Horton Mudgett and his wife, formerly Theodate Page Price. His early criminal career was based on fraud and forgery, including a cure for alcoholism, real estate scams, and a machine that purported to make natural gas from water. Holmes earned a doctor's degree from the University of Michigan.

On 8 July 1878, he married Clara A. Lovering of Alton, New Hampshire. On 28 January 1887, he (bigamously) married Myrta Z. Belknap in Minneapolis, Minnesota; they had a daughter named Lucy. He filed a petition for divorce from his first wife after marrying his second, but it never became final. He married his third wife, Georgiana Yoke, on 9 January 1894. He was also the lover of Julia Smythe, the wife of Ned Connor, one of his trusted associates. She later become one of his victims.

He managed to secure a Chicago pharmacy by defrauding the pharmacist, and built a block-long, three-story building on the lot across the street. He called this building "The Castle," and opened it as a hotel for the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893. The bottom floor of the Castle contained shops, the top his personal office, and the middle floor a maze of over one hundred windowless rooms. Over a period of three years, Holmes selected female victims from among his hotel's guests, and tortured them in soundproof and escapeproof chambers fitted with gas lines that permitted Mudgett to asphyxiate the women at any time. Holmes had repeatedly changed builders, to ensure that no one truly understood the design of the house he had created who might report it to the police. Once dead, the victims' bodies went by chute to the basement, where they were either sold to medical schools or cremated and placed in lime pits for destruction.

Following the World's Fair, Holmes left Chicago and apparently murdered people as he traveled around the country. He was arrested in 1895 when he was discovered with the body of a former business associate, Benjamin Pitezel, and three of his children.

The same year, Holmes's "castle" in Chicago burnt down on August 19, revealing the carnage therein to the police and firemen. His habit of taking out insurance policies on some of his victims before killing them may have eventually exposed him regardless. The number of Holmes' victims has typically been estimated between 20 to 100, and even as high as 200. These victims were primarily women, but included some men and children.

Holmes was put on trial for murder, and confessed to 27 murders (in Chicago, Indianapolis and Toronto) and six attempted murders. He was hanged on May 7, 1896, in Philadelphia. It was reported that when the executioner had finished all the preliminaries of the hanging, he asked, "Ready, Dr. Holmes?", to which Holmes said, "Yes. Don't bungle." The executioner did "bungle," however, because Holmes' neck did not snap immediately; he instead died slowly and painfully of strangulation over the course of about 15 minutes.

References

Borowski, John (Director), H.H. Holmes, America's First Serial Killer (Motion picture documentary), Waterfront Productions, 2004.

Borowski, John (2005). Dimas Estrada (editor) The Strange Case of Dr. H. H. Holmes. ISBN 0975918516.

See also the list of many references on the Memorabilia page.

Geary, Rick (2004). The Beast of Chicago: The Murderous Career of H. H. Holmes. Nantier, Beall & Minoustchine.

Larson, Erik (2003). The Devil in the White City. New York: Vintage Books.

Schecter, Harold (1994). Depraved. New York: Pocket Books.

Michod, Alec (2004). The White City. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Adams, Cecil, "Did Dr. Henry Holmes kill 200 people at a bizarre "castle" in 1890s Chicago?", The Straight Dope, 1979-07-06.

Herman Webster Mudgett (May 16, 1861 – May 7, 1896), better known under the alias of Dr. Henry Howard Holmes, was an American serial killer. Holmes opened a hotel in Chicago for the 1893 World's Fair, which he built himself and was the location of many of his murders. While he confessed to 27 murders, of which 9 were confirmed, his actual body count could be as high as 250. He took an unknown number of his victims from the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, which was less than 2 miles away from his "World's Fair" hotel.

The case was notorious in its time and received wide publicity via a series of articles in William Randolph Hearst's newspapers. Interest in Holmes' crimes was revived in 2003 by Erik Larson's The Devil in the White City, a best-selling non-fiction book that juxtaposed an account of the planning and staging of the World's Fair with Holmes' story.

Early life

Mudgett was born in Gilmanton, New Hampshire. He was the son of Levi Horton Mudgett and Theodate Page Price. The family was descended from among the first settlers to the area. He grew up with a father who was a strict disciplinarian, and he was often bullied as a child. He claimed that, as a child, he had been forced by other students to view and touch a human skeleton after they found out about his fear of the local doctor's office. The bullies had initially brought him there to scare him, but instead he was utterly fascinated.

Herman Mudgett graduated from the University of Michigan Medical School in 1884. While enrolled, he stole bodies from the school laboratory. Disfiguring the corpses and claiming that the people had been accidentally killed, Mudgett collected insurance money from policies which he had taken out on each one. After graduating, he moved to Chicago to practice pharmacy. He also began to engage in a number of shady businesses, real estate, and promotional deals under the name "H. H. Holmes".

On July 8, 1878, Holmes married Clara A. Lovering of Alton, New Hampshire. On January 28, 1887, he married Myrta Z. Belknap in Minneapolis, Minnesota; he was still married to Lovering at the time, making him a bigamist. He and Belknap had a daughter named Lucy Theodate Holmes, born 4 July 1889 in Englewood, Illinois.

The family of three resided in the upscale Chicago suburb of Wilmette—although Holmes spent most of his time in the city tending to business. He filed a petition for divorce from his first wife after marrying his second, but the divorce was never finalized. He married his third wife, Georgiana Yoke, on January 9, 1894. He also had a relationship with Julia Smythe, the wife of Ned Connor, a one-time employee of his who later fled Chicago. Julia became one of Holmes' victims.

Chicago and the "Murder Castle"

While in Chicago, Holmes came across Dr. E.S. Holton's drugstore. It was located at the corner of Wallace and 63rd Street, in the neighborhood of Englewood. Holton was suffering from cancer while his wife minded the store. Through his charm, Holmes got a job there and then manipulated her into letting him purchase the store. The agreement was that she could still live in the upstairs apartment even after Holton died. Once Holton died, Holmes murdered Mrs. Holton and told people she was visiting relatives in California. As people started asking questions as to when she would be coming back, he elaborated the lie and told them she loved it so much in California that she decided to live there.

Holmes purchased a lot across from the drugstore, where he built his three-story, block-long "Castle"—as it was dubbed by those in the neighborhood. It was opened as a hotel for the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893, with part of the structure used as commercial space.

The ground floor of the Castle contained, aside from Holmes' own relocated drugstore, various shops (a jeweler, for example), while the upper two floors contained his personal office as well as a maze of over one hundred windowless rooms with doorways that would open to brick walls, oddly angled hallways, stairways to nowhere, doors that could only be opened from the outside, and a host of other strange and labyrinthine constructions. Holmes had repeatedly changed builders during the initial construction of the Castle to ensure that only he fully understood the design of the house he had created, thereby decreasing the chances of any of them reporting it to the police.

Over a period of three years, Holmes selected female victims from among his employees (many of whom were required as a condition of employment to take out life insurance policies for which Holmes would pay the premiums but also be the beneficiary), lovers and hotel guests, and would torture and kill them. Some were locked in soundproof bedrooms fitted with gas lines that permitted him to asphyxiate them at any time. Some victims were locked in a huge bank vault near his office; he could sit and listen as they screamed, panicked and eventually suffocated, due to the fact that the vault was sound-proof.

The victims' bodies went by a secret chute to the basement, where some were meticulously dissected, stripped of flesh, crafted into skeleton models, and then sold to medical schools. Holmes also cremated some of the bodies or placed them in lime pits for destruction. Holmes had two giant furnaces as well as pits of acid, bottles of various poisons, and even a stretching rack. Through the connections he had gained in medical school, he was able to sell skeletons and organs with little difficulty. Holmes picked one of the most remote rooms in the Castle to perform hundreds of illegal abortions. Some of his patients died as a result of his abortion procedure, and their corpses were also processed and the skeletons sold.

Capture and arrest

Following the World's Fair, with creditors closing in and the economy in a general slump, Holmes left Chicago. He next appeared in Fort Worth, Texas, where he had inherited property from two railroad heiress sisters, one of whom he had promised marriage and both of whom he murdered. There, he sought to construct another castle along the lines of his Chicago operation.

However, he soon abandoned this project, finding the law enforcement climate in Texas inhospitable. He continued to move about the United States and Canada, and while it seems likely that he continued to kill, the only bodies discovered which date from this period are those of his close business associate and three of the associate's children.

In July 1894, Holmes was arrested and briefly incarcerated for the first time, for a horse swindle that ended in St. Louis. He was promptly bailed out, but while in jail, he struck up a conversation with a convicted train robber named Marion Hedgepeth, who was serving a 25-year sentence.

Holmes had concocted a plan to bilk an insurance company out of $20,000 by taking out a policy on himself and then faking his death. Holmes promised Hedgepeth a $500 commission in exchange for the name of a lawyer who could be trusted. He was directed to Colonel Jeptha Howe, the brother of a public defender, and Howe found Holmes’ plan to be brilliant. Holmes' plan to fake his own death failed when the insurance company became suspicious and refused to pay. Holmes did not press his claim; instead he concoted a similar plan with his associate, Pitezel.

Pitezel had agreed to fake his own death so that his wife could collect on the $10,000 policy, which she was to split with Holmes and a shady attorney, Howe. The scheme, which was to take place in Philadelphia, was that Pitezel should set himself up as an inventor, under the name B. F. Perry, and then be killed and disfigured in a lab explosion. Holmes was to find an appropriate cadaver to play the role of Pitezel.

Holmes then killed Pitezel, although some have argued that Pitezel, an alcoholic and chronic depressive, might in fact have committed suicide. Forensic evidence presented at Holmes' later trial, however, showed that chloroform was admistered after Pitezel's death, presumably to fake suicide. Holmes proceeded to collect on the policy on the basis of the genuine Pitezel corpse.

He then went on to manipulate Pitezel's wife into allowing three of her five children (Alice, Nellie, and Howard) to stay in his custody.

The eldest daughter and baby remained with Mrs. Pitezel. He traveled with the children through the northern United States and into Canada. Simultaneously he escorted Mrs. Pitezel along a parallel route, all the while using various aliases and lying to Mrs. Pitezel concerning her husband's death (claiming that Pitezel was in hiding in South America) as well as lying to her about the true whereabouts of her other children—they were often only separated by a few blocks.

No Words for this

A Philadelphia detective had tracked Holmes, finding the decomposed bodies of the two Pitezel girls in Toronto. He then followed Holmes to Indianapolis.

There Holmes had rented a cottage. He was reported to have visited a local pharmacy to purchase the drugs which he used to kill Howard Pitezel, and a repair shop to sharpen the knives he used to chop up the body before he burned it.

The boy's teeth and bits of bone were discovered in the home's chimney.

In 1894 the police were tipped off by his former cell-mate, Marion Hedgepeth, whom Holmes had neglected to pay off as promised for his help in providing Howe. Holmes's escapade ended when he was finally arrested in Boston on November 17, 1894, after being tracked there from Philadelphia by the Pinkertons. He was held on an outstanding warrant for horse theft in Texas, as the authorities had little more than suspicions at this point and Holmes appeared poised to flee the country, in the company of his unsuspecting third wife.

After the custodian for the Castle informed police that he was never allowed to clean the upper floors, police began a thorough investigation over the course of the next month, uncovering Holmes' efficient methods of committing murders and then disposing of the corpses. A fire of mysterious origin consumed the building on August 19, 1895, and the site is currently occupied by a U.S. Post Office building.

The number of his victims has typically been estimated between 20 and 100, and even as high as 230, based upon missing persons reports of the time as well as the testimony of Holmes' neighbors who reported seeing him accompany unidentified young women into his hotel—young women whom they never saw exit.

The discrepancy in numbers can perhaps best be attributed to the fact that a great many people came to Chicago to see the World's Fair but, for one reason or another, never returned home. The only verified number is 27, although police had commented that some of the bodies in the basement were so badly dismembered and decomposed that it was difficult to tell how many bodies there actually were. Holmes' victims were primarily women (and primarily blonde) but included some men and children.

While Holmes sat in prison in Philadelphia, not only did the Chicago Police investigate his operations in that city, but the Philadelphia Police began to try to unravel the whole Pitezel situation—in particular what had happened to the three missing children. Philadelphia detective Frank Geyer was given the task of finding out. His quest for the children, like the search of Holmes' Castle, received wide publicity. His eventual discovery of their remains essentially sealed Holmes' fate, at least in the public mind.

Holmes was put on trial for the murder of Pitezel and confessed, following his conviction, to 27 murders in Chicago, Indianapolis and Toronto, and six attempted murders. Holmes was paid $7,500 by the Hearst Papers in exchange for this confession. He gave various contradictory accounts of his life, initially claiming innocence, and later that he was possessed by Satan. His facility for lying has made it difficult for researchers to ascertain any truth on the basis of his statements.

One has to think only those in tune with satan harm children.

Not to mention other satanists and serial killers' connection to giving satan credit.

He requested that he be buried in concrete so that no one could ever dig him up and dissect his body, as he had dissected so many others. This request was granted.

On New Year's Eve, 1910, Marion Hedgepeth, who had been pardoned for informing on Holmes, was shot and killed by a police officer during a hold up at a Chicago saloon. Then, on March 7, 1914, a story in the Chicago Tribune reported the death of the former caretaker of the Murder Castle, Pat Quinlan. Quinlan had committed suicide by taking strychnine, and the paper reported that his death meant "the mysteries of Holmes' Castle" would remain unexplained. Quinlan's surviving relatives claimed Quinlan had been "haunted" for several months before his death and that he could not sleep.

In the early 19th century Philadelphia was the largest, wealthiest city in the country. Where other towns had wooden shacks and dirt roads, Philly had white marble buildings and cobblestone streets busy with horse-and-buggy traffic. It wasn't only the center of a new nation's political life. It was the height of fashion and high society.

By the late 19th century Philadelphia's grand status had evolved even further--with the largest population of African-Americans in the North, and painters like Thomas Eakins forging a link between this city and Paris. City Hall, that opulent example of Second Empire French architecture, was crowned with a statue of William Penn in 1894, as if to cement its grandeur. Philadelphia was so respected, a company chose the city's name to lend culinary sophistication to its cream cheese.

But the city's shine diminished in the last years of the century. Political power moved to Washington, and cultural power slid toward New York. Philadelphia became industrial, and with that industry came dirt, crowds and crime. It was this Philadelphia--half gleaming symbol, half grimy pioneer territory--that H. H. Holmes invaded, taking advantage of the confusion a city on the brink engendered.

Holmes was born Herman Webster Mudgett in the small village of Gilmanton, N.H., in May 1861. If Mudgett or his brother or sister were bad, their strict Methodist parents sent them to the attic for a full day without speaking or eating. Mudgett's father was especially abusive after he'd been drinking--which was often.

Mudgett was curiously detached from the start. He'd attack animals in the woods and dissect them while they were still alive. And he had no friends--the one he did have died while the two were playing. Despite his odd upbringing--and the distance he kept from other children, who found him arrogant--he grew into an imposing young man. He was polished, bright and handsome, and was good at making people feel special. At 16 he left home, became a teacher and cajoled a young woman into marrying him. At 19 he went to medical school, and left his wife.

In the 1880s Mudgett--now Holmes--came to Philadelphia. He got a job as a "keeper" at the Norristown Asylum, which is now Norristown State Hospital. The experience horrified him, so he took a position at a drugstore instead. After a customer who took medicine he dispensed died, he left town.

His criminal career kicked into high gear in Englewood, Ill., just outside of Chicago, where he worked as a pharmacist and impressed people not only with his medical knowledge but with his power over women--who flocked to the store just to flirt with him. The proprietress of the drugstore sold it to Holmes after her husband died, but never saw any money from Holmes. When she filed a lawsuit, Holmes told people she'd gone to see family in California. She was never heard from again.

Holmes built the Castle in the vacant lot across from the drugstore in the fall of 1888, the same year Jack the Ripper started killing women in London. Holmes served as the architect, and when the building was finished two years later, he marketed it as a boarding house for young single women who were visiting Chicago or coming from neighboring towns to find a better life. As many as 50 of the women who came to the Castle during the World's Fair never left.

Two women, one of them pregnant, were told if they wrote the letters, they'd go free. But as soon as they signed the letters Holmes killed them.

In his confession, he wrote, "These were particularly sad deaths, both on account of the victims being exceptionally upright and virtuous women and because Mrs. Sarah Cook, had she lived, would have soon become a mother."

Because it was a boarding house, the Castle had a reception room, a waiting room and several rooms for residents. Aside from those and some hallways, the house was comprised of secret chambers, trap doors, hidden laboratories and rooms devoted to killing people.

One of them, which the media dubbed "the Vault," was a walk-in room with iron walls and gas jets that Holmes controlled from his bedroom. There was a dumbwaiter for lowering bodies and a "hanging chamber." He had a medieval torture rack in the basement, and a greased chute that went from the roof to the basement so he could dump bodies. He had a maze he sent his victims through and a terrifying "blind room."

Several rooms were airtight and without windows--one of them fitted with iron plates, another lined with asbestos. There was an asphyxiation chamber with gas jets that could be turned into blowtorches, perhaps to roast people alive.

When the police inspected the Castle after Holmes was in jail, they were horrified. It was beyond belief--for any century, but especially the 1800s.

There were claw marks on the walls of the Vault from people who'd tried to escape. In the basement there was a bloodstained dissecting table and surgical instruments. There was a vat of acid with human bones in it, and piles of quicklime, one of which yielded a girl's dress. There was an enormous stove to burn bodies in--and a stovepipe with human hair in it.

They found human skulls, a shoulder blade, ribs, a hip socket and countless other remains. They also found--perhaps more disturbingly--Holmes' victims' belongings: watches, buttons, photographs, half-burnt ladies' shoes.

The only comfort inspectors had as they traipsed through the building was that Holmes was already in custody at Philadelphia's Moyamensing Prison. But the story was far from over.

The tale of H. H. Holmes has been told before. It was told by Philly detective Frank Geyer in his book written immediately after the case. It was told in the trial transcript. It was the subject of the exhaustively researched true-crime book Depraved by Harold Schecter, and was featured in Erik Larson's The Devil in the White City, which juxtaposes Holmes' Chicago crimes with the story of the Chicago World's Fair. It was told in the media at the time and is also told--though not to many--in John Borowski's documentary H.H. Holmes: America's First Serial Killer, which is awaiting distribution.

One of his relationships was with Minnie Williams, who was a Texas heiress. Minnie's sister, Nannie, came to visit for the Exposition, but they both vanished in 1893. Detectives would later find Nannie's footprint in the Vault, which Holmes admitted was made "in the violent struggles before her death." Minnie's will left everything to Holmes' personal assistant, Benjamin Pitezel, who lived nearby with his wife and four children.

When Holmes and Pitezel went to Texas to try to collect on Minnie's will, they were almost arrested, so they left town. Holmes was soon picked up in St. Louis for stealing from a drugstore, but was released shortly thereafter.

For reasons unknown, Holmes chose Philadelphia as the site for his next venture. He insured Pitezel for $10,000 and made Pitezel's wife, Carrie--who'd stayed behind in St. Louis--the beneficiary. The plan was to fake Pitezel's death, collect the money from the insurance company and split the profits between them.

He installed Pitezel in a fake patent dealership at 1316 Callowhill St., which was right in front of the city morgue. Pitezel hung a sheet of muslin that read "BF PERRY PATENTS BOUGHT AND SOLD" outside the building to make it look legitimate. (Holmes had an apartment at 1905 N. 11th St., which is now on Temple's main campus.)

A patent-seeking carpenter named Eugene Smith came to the office one day in September 1894 looking for the man he assumed was named Perry. No one was in, but the door was open. The Holmes-Pitezel Case: A History of the Greatest Crime of the Century, by Detective Geyer, says Smith "hallooed" several times but didn't get a response.

When Smith went upstairs, Geyer writes, "His gaze met a sight that chilled his blood." It was a man lying on his back, his face "disfigured beyond recognition by decomposition and burning." It seemed there'd been some kind of explosion, and the rigid body was singed on one side--including half his mustache. There was, according to Geyer's book, "a considerable quantity of fluid" spreading out for more than a foot around the body.

The only person who knew the true identity of the corpse was H.H. Holmes, and he was more than happy to come forward to identify it as Ben Pitezel's. He even brought Pitezel's daughter, Alice, with him from St. Louis to seal the deal. Pitezel's wife, Carrie, still believed it was all a scheme, and that Ben was hiding out and waiting for her.

In his confession, Holmes said he'd been planning to kill Pitezel from the moment he met him, and that everything he did with the man, for seven years, led up to that very moment. Such a long-term investment, wrote Holmes, "furnishes a very striking illustration of the vagaries in which the human mind will, under certain circumstances, indulge," and compares the anticipation of Pitezel's murder to "the seeking of buried treasure at the rainbow's end."

The reality of Pitezel's death was far worse than what Eugene Smith saw. Holmes wrote in his confession that he went to 1316 Callowhill and found Pitezel drunk and passed out, as he expected. (Holmes had earlier forged a series of hurtful letters from Pitezel's wife, which caused Pitezel to start drinking--all part of the plan.) He bound Pitezel's hands and feet, and then he wrote, "I proceeded to burn him alive by saturating his clothing and his face with benzine and igniting it with a match. So horrible was this torture that in writing of it I have been tempted to attribute his death to some humane means--not with a wish to spare myself, but because I fear that it will not be believed that one could be so heartless and depraved."

After he collected the money, Holmes went to St. Louis and convinced Pitezel's widow to lay low too. He offered to place her children with his cousin, whom he called "Minnie Williams," until she and Ben could come out of hiding.

Geary writes, "Through the man's unimaginable powers of persuasion, Carrie agreed to surrender two more of her children." There was no pragmatic reason for Holmes to take the children. But as he wrote in his confession, he chose Pitezel as a victim "even before I knew he had a family who would later afford me additional victims for the gratification of my bloodthirstiness."

And so began the horrible journey of Alice, Nellie and Howard Pitezel.

A letter to Carrie Pitezel from Alice Pitezel, dated Sept. 20, 1894:

Just arrived Philadelphia this morning ... I am going to the Morgue after awhile ... We stopped off at Washington, Md., this morning, and that made it six times that we transferred to different cars ... Mr. H says that I will have a ride on the ocean. I wish you could see what I have seen. I have seen more scenery than I have seen since I was born ... You had better not write to me here for Mr. H. says that I may be off tomorrow.

A letter to Carrie Pitezel from Alice Pitezel, dated Sept. 21, 1894:

I have to write all the time to pass away the time ... Mama have you ever seen or tasted a red banana? I have had three. They are so big that I can just reach around it and have my thumb and next finger just tutch. I have not got any shoes yet and I have to go a hobbling around all the time. Have you gotten 4 letters from me besides this? ... I wish that I could hear from you ... I have not got but two clean garments and that is a shirt and my white skirt. I saw some of the largest solid rocks that I bet you never saw. I crossed the Patomac river."

Sources, Connecting Reports and Articles

http://mysteriouschicago.com/hh-holmes-vs-the-lumber-men-from-hell/

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/36541553/the-inter-ocean/

https://allthatsinteresting.com/hh-holmes

https://joshuashawnmichaelhehe.medium.com/h-h-holmes-576dde2ac91c

https://murderpedia.org/male.H/h/holmes.htm

Borowski, John (2005). Dimas Estrada (editor) The Strange Case of Dr. H. H. Holmes. ISBN 0975918516.

See also the list of many references on the Memorabilia page.

Geary, Rick (2004). The Beast of Chicago: The Murderous Career of H. H. Holmes. Nantier, Beall & Minoustchine.

Larson, Erik (2003). The Devil in the White City. New York: Vintage Books.

Schecter, Harold (1994). Depraved. New York: Pocket Books.

Michod, Alec (2004). The White City. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Adams, Cecil, "Did Dr. Henry Holmes kill 200 people at a bizarre "castle" in 1890s Chicago?", The Straight Dope, 1979-07-06.