Conveniently but unfortunately, it didn’t take me too long to find another example of demolished Black musical history in Philadelphia.

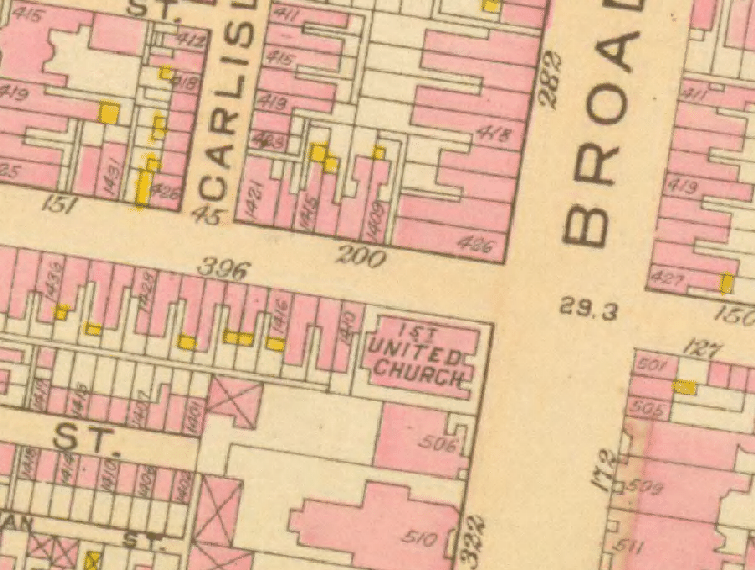

Remember when I told you that the Standard was only one of John T. Gibson’s theaters? Well, I found the next one: The Dunbar located at the corner of Broad and Lombard Streets. Though he bought the building from the original owners in 1921, coincidentally, the Theater itself has strong ties to 1918. As you can see from my Philadelphia 1910 Atlas screengrab below (to learn more about exploring Philly’s digital maps, head to philageohistory.org), the lot at Broad and Lombard had long been home to the First United Church, but by 1918, the building was long abandoned and in need of a repurposing. According to the Philadelphia Tribune, there had been talk of a theater, but nothing ever came to fruition.

Until 1918.

Two wealthy gentleman bought the property and plans formed soon thereafter. E. C. Brown and Andrew Stevens Jr. were, like Gibson, the talk of black Philadelphia. Stevens was the only black member of the State Republican Committee, Brown was president of the largest black realty corporation in New York City, and they happened to own a prominent bank just across the street from their new property. However, their success, wealth, and fame certainly did not preclude them from the hardships and humiliations of Philadelphia’s notoriously segregated neighborhoods. In fact, the owners of the Forrest Theater (then on Broad and Sansom Streets) had refused to allow Brown to even walk through its doors.

The Forrest Theatre that barred entry to African Americans can be seen on the right at its Broad and Sansom location. The current Forrest Theatre was built in 1927 and stands at 11th and Walnut.

So, on March 16, 1918, the Brown and Stevens’ Dunbar Amusement Company announced plans to build a theater for black acts and audiences, particularly audiences looking for a higher class of entertainment than the raucous vaudeville up the street at the Standard. These men were capitalizing on the influx of southern black migrants and also providing a service to an entire segment of Philadelphia’s population that was barred from leisure in the city. As the Philadelphia Tribune aptly explains:

The white theatres and owners are and have been for some time drawing the color line and we have but one theatre owned and controlled by our race in this city, and when it is full, which it is at every performance, there is practically no place for our people to go.

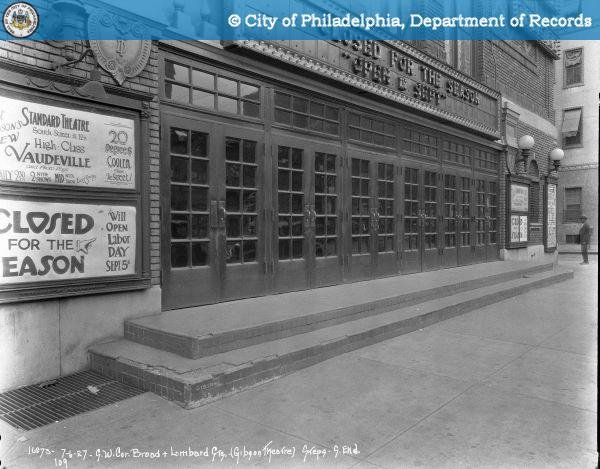

The Dunbar Amusement Company eventually sold the theatre to Gibson (who renamed it the Gibson Theatre), so it remained owned and operated by the African American community; however, while Gibson’s successfully attracted interracial audiences to both of his venues the Great Depression forced him to sell the space to white owners who renamed it the Lincoln. The building would close and reopen several times throughout the turbulent 1930s, but eventually closed it’s doors for good in 1955. This building, once a haven for audiences of color, has also been torn down; its physical memory substituted and replaced by a blue square marker.

Here is a photograph of the Gibson Theatre marquee as it appeared in 1927. The building has since been demolished, and the site is now home to the Philadelphia Department of Public Health.

Sources include: {"THE DUNBAR THEATRE." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-2001), Mar 16, 1918., photographs courtesy of the Philadelphia City Archives}

100% of the SBD rewards from this #philly5151 post will support the Philadelphia History initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment is part of a graduate course at Temple University's Center for Public History and is exploring history and empowering education to endow meaning. To learn more click here.