History has a curious way of working in cycles - or that’s what appearances would lead us to believe. The year 1968, as we talked about last time, was special in many ways. Today we’ll begin to consider a related observation: that 1918 was also another very dynamic year.

Source: The Library Company of Philadelphia

Source: The Library Company of Philadelphia

Extraordinarily dynamic, as we’ll see.

Is there deeper meaning to the fact that 1968 was 50 years ago and that 1918 was 100 years ago? Or is it all one big, symmetrical, random, cosmic coincidence? Is there anything to it, that the most memorable and impactful times seem to happen in fifty year cycles? (And that we’re apparently in for another one in 2018?)

Does time simply run its course, or does it evolve into histories that run in 50-year cycles, as the Old Testament long ago professed (see Leviticus 25:8-13). How should we consider this undeniable, possibly universal urge to organize time in patterns that bridge lives, generations and calendars?

How should we remember the past and make it interesting, if not actually useful, for the future?

As a longtime blogger at PhillyHistory.org, I couldn’t help from repeatedly noticing how 1918’s footprint seemed both outsized and compelling. There was so much to look back at, so much to consider, to learn from...so much to remember.

Here’s a handful of stories about 1918 presented at PhillyHistory:

Liberty Unveiled

Little “blue-eyed, pink-cheeked” Nona Martin, the five-year-old from Chestnut Hill, stood motionless, “awed by the numberless masses that stretched away before her vision down Broad Street, as far as the eye could see.” By her side, on the platform, was her grandfather, William G. McAdoo, the “tall, gaunt, commanding” Treasury Secretary. Behind them loomed the giant statue, draped in white. ...

Source: PhillyHistory.org

No Coal; No Peace – The Story of Philadelphia’s 1918 Coal Famine

Every day in the depths of winter, coal cars trundled down Washington Avenue supplying the city’s lifeblood. You wouldn’t know it looking at the trackless six lanes of blacktop today, but locomotives once hauled hundreds of thousands of tons of anthracite to at least thirty coal yards between 2nd and 25th Streets. Coal powered nearly every factory and heated nearly every shop, school, theater and home—a quarter of a million of them. On extremely cold days, a large school, just one of the city’s 231, would consume as much as 10 tons. The University of Pennsylvania needed 150 tons to stay open. In all, the city could burn as much as 19,000 tons. Every day. And on the first frigid week of January 1918, it all ground to a halt. ...

Aftermath of the Race Riots of 1918: The Station House at 20th and Federal

After a weekend of rioting the likes of which Philadelphia had never seen, families of the deceased planned funerals for two of the men killed in the mayhem. Grieving for their fallen 24-year-old patrolman, the McVeys would have Requiem Mass sung at St. Anthony’s Catholic Church, 24th and Fitzwater streets. “Thousands of persons, hours before the services started, began assembling along the route of the funeral procession,” reported the Inquirer. Lieutenant Harry Meyers of the 17th Police District at 20th and Federal Streets would send a 30-man “guard of honor” and largest floral wreath. Six officers from the station stepped up as pallbearers. They’d attempt to console McVey’s bereft mother, who responded: “I have but one wish…to live long enough to see my poor boy’s death avenged. He didn’t deserve to meet with such an end, to be killed by the bullet of a negro.” ...

Source: PhillyHistory.org

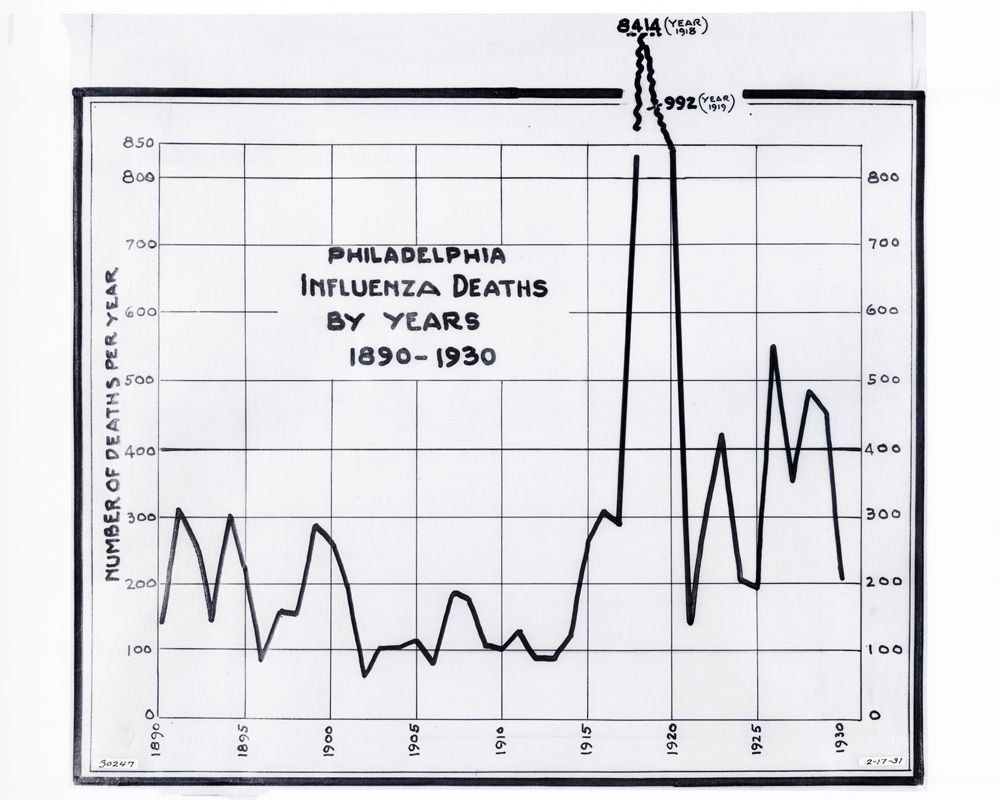

1918: Death on the Home Front

September had been tough, especially the middle of the month, when more than a quarter of the soldiers at the Frankford Arsenal had been hospitalized with the “Spanish Flu.” On October 1, as the deaths were counted, the Inquirer grasped for a positive tone, pointing out the number of new cases had actually fallen off toward the end of the previous month. Commander R.W. Plummer of the Fourth Naval Reserve District also tried to offer hope, that maybe, just maybe, “the crest of the epidemic of Spanish Influenza has passed.” The newspaper encouraged denial: “Talk of cheerful things instead of disease, why close down “public schools, theatres, churches, and many other places. … The authorities seem to be going daft. What are they trying to do, scare everybody to death?” ...

The Clinical Ampitheatre and Surgery as Spectacle

Demolition for the Parkway proceeded through the northwest quadrant of Center City like Sherman’s March through Georgia. Promising a civic and cultural boulevard, planners took no prisoners, even as they encountered the city’s best architectural gems.Only one hiccup in the way of progress was the Medico-Chirurgical Hospital. But this, too, eventually took the fall. The hospital’s clinical ampitheatre, just west enough on Cherry Street to survive a couple of decades longer, perpetuated the original, old-school Philadelphia sin of perpendicularity. In the 20th century, at least in this quadrant of Penn’s original grid, planners switched staid for sparkle. Perpendicularity had given way to diagonality. Anything else, everything else, would be sacrificed at the altar of the City Beautiful. ...

Source: PhillyHistory.org

Censoring Philly Street Dance after the Shimmy Ship had Sailed

“Those moaning saxophones,” fretted John R. McMahon in the Ladies’ Home Journal, “call out the low and rowdy instinct.” And with degrading names like “the cat step, camel walk, bunny hug, turkey trot,” McMahon figured jazz dance mocked the dignified traditions of social dance. Most insidious of all was a move they called the shimmy. “The road to hell is too often paved with jazz steps,” McMahon wrote in an article titled, “Unspeakable Jazz Must Go!” The shimmy rode in with Spencer Williams’ popular song, “Shim-Me-Sha-Wabble,” from 1917. Within a few years, the shimmy had just about taken over White America’s dance halls and cabarets; thriving on stage, in recordings, all the while shaking America’s sense of decency. ...

In 2018, one hundred years later, we recognize there was something special, many things actually, about 1918.

And while the past sometimes fades away, other times it evolves into what we’ve come to call “history,” an identified past that (ironically) grows more present, more weighty. It appears that 1918 has declared its intentions to stay and to move from the ranks of the mere past to the venerable. Now, in 2018, it’s our turn to declare our intentions as to how it would be received and presented.

How will we choose to remember 1918?

Followers of @phillyhistory will be looking at these and other issues of time, place and memory beginning this month and continuing through April as part of a History 5151, a graduate course and a crypto-experiment at Temple University’s Center for Public History. This Steemit account, in partnership with @sndbox, is a dedicated space to explore history, empower education and endow meaning. Stay tuned for more from Professor Kenneth Finkel, @kenfinkel in Temple University’s College of Liberal Arts.