This is the second part of a little series of articles reflecting on the past year -- my first as a full-time permanent resident in Japan. You can read part one here.

1. Learning to Farm the Japanese Way

Part of the original plan in coming to Japan was to set myself up as an organic market gardener, specialising in French heritage varieties of vegetables and herbs (you can read more about this in some of my other articles), putting into practice what I had learnt when I lived in France. Because it seemed to me to be a gentler and more diplomatic way of settling in that just turning up, renting some land and getting on with it, I decided to enlist as an apprentice -- or kenshūsei 研修生 in Japanese -- on a organic farm in Nagano (where I thought the climate most suitable to not just the kind of crops I intend to grow but to myself, also: I come from Scotland originally, remember!).

This turned out to be a whole lot harder than I had imagined. Not so much because the days were long (6 AM to 6 PM with no more than one break for lunch) but more because it was so psychologically and emotionally draining. I should have expected it, but it turned out that learning farming in Japan is not so much about learning to farm as it is about learning to be Japanese. Well, as much as I like Japan and speak Japanese, I'm not Japanese. And, as far as the farming side of things was concerned, I already knew what I wanted to do, and how, and it wasn't what these guys were doing on their farm. I did, however, manage to accomplish what I came to do: to meet people, to learn how they work and live, to settle into the community slowly and gently, and to be accepted. And to find land and the means to work it. (I won't be saying much more about that here, because I'll be devoting a later article to the subject...).

2. Surprises, surprises

It wasn't long before I began to realise that farming in Japan was not the simple affair I had expected it to be. Whilst I'm really in no position, ultimately, to say whether any of what I saw and helped do was good or bad, a lot of it really surprised me. It's also possible, I guess, that one day it may all seem to make perfectly good sense but for now, I can't help feeling that a very large part of time was spent doing things that I was previously taught specifically to not do. So that's what I'm going to start with.

(Over-)attention to Detail

The first major surprise was the huge amount of time devoted to chōsei 調整 (conditioning, adjustment, calibration...), the Japanese word used to refer to post-harvest processing: cleaning, bagging, boxing etc. Whereas in France this often amounted to no more than pulling off a few damaged leaves on a lettuce, or removing with your thumb a particularly large lump of soil still clinging to a carrot or turnip root, I quickly learnt that in Japan chōsei is a serious and time-consuming affair. Not only did it involve scissors, tweezers, buckets of water, brushes, knives, cloths and innumerable other implements, it took up about one third of the total time spent on the farm where I worked and resulted, I estimate, in no more than one third of the total amount of vegetables grown actually reaching the customer.

It soon dawned on me that what is often praised abroad when discussing Japanese culture -- an intense attention to minutiae -- seems far less romantic and, even, economic, when experienced up close. In short, as a European having been taught organic farming in France, it seemed as though the Japanese were continually placing far greater importance in the appearance of their vegetables than they were in either the economic viability of their business or even the taste of their products. Worrying so much about appearance and presentation also makes for a rather tense work-environment: whereas in France lunch breaks had been generous, cigarettes were smoked liberally, work was enjoyed and vegetables were sold pretty much as they came out of the field, here in Japan the all-consuming attention to detail and obsession with things been done in a very specific manner meant that it was relatively hard to delegate tasks and occasionally resulted in jobs having to be entirely redone. At first I thought that my misgivings were purely down to not being Japanese, but then I recalled some phrases I had heard Curtis Stone often use in his videos (highly recommended if you haven't already heard of him...): "for optimum effectiveness, abandon perfection," "perfection is not worth the time" and, above all, "it takes 50% of your time to achieve 85% effectiveness and quality; it takes the same amount of time to get the further 15%: is it worth it?!" So, whilst the Japanese may be particularly talented in this area, it certainly isn't something that only the Japanese do. Just think of the tomatoes, apples and other fruit and veg sold in supermarkets all over the world: if they all have to be so shapely and shiny, it is precisely because we have been bred to demand (visual) perfection, without understanding the huge burden that that piles upon the shoulders of those who produce them and the waste that it entails.

The (Over-)Importance of Machinery

The kind of organic farming I had studied and practiced in France is routinely called market-gardening (maraîchage in French): suited to small sized farms -- commonly referred to as micro-farms (micro-fermes in French) -- it optimises land-use by reducing to an absolute minimum the necessity for machines, relying instead on intensive (and highly productive) human labour. Since Japanese farms are on average very small (a good-sized farm may only be 5 hectares), it seemed to be to be the ideal way to work the land and I expected to see something very like it here. I should have know better, however, because it seemed to me to be the total opposite: every farm, no matter how small, has a tractor of some sort, and every field is routinely ploughed, reformed and cleaned to within an inch of its life. While there are undoubtedly many different causes for this (I am inclined to point to two in particular: the very high average age of farmers in Japan (in Nagano prefecture 30% of farmers in 2015 were over 65) which means that despite their famous good health, they lack the physical strength to do much physical work; and the unholy alliance between the all-powerful JA (Japan Agriculture Cooperatives Group) and Japanese machine manufacturers which results in Japanese farmers being used as a means of propping up Japanese industry whether they need it or not), the results are everywhere the same:

- Soil compaction: while the topsoil may be momentarily soft and fluffy, a dead pan forms just below the surface, where the plough scrapes repeatedly against the subsoil, causing drainage problems and making it hard for root crops to penetrate very deeply

- Weeds: as the plough turns it brings weed-seeds up to the surface, where they are all too happy to germinate

- Stones: along with weed seeds, stones are routinely brought up to the surface

- Erosion: because the life in the soil is gradually killed off, its structure ruined and any natural cover-crops removed, the soil is susceptible to be being blown or washed away

- Loss of time and money: all machines have to be paid for, they need fuel and working them requires time

- Standardisation of crops and bed sizes: while Japanese tractors may be smaller than most western models, they still take up room in the field and make it necessary to plant crops wider apart than is required by the plants themselves

Complaining to my wife about that having to put up with -- and often enough to take part in myself -- these practices made me uncomfortable, she reminded me that seeing with my own eyes the side-effects that I had up until then only been warned about was in itself a worthwhile experience. I knew she was right, but it sure didn't make it any easier...

Disregard for Seed Varieties

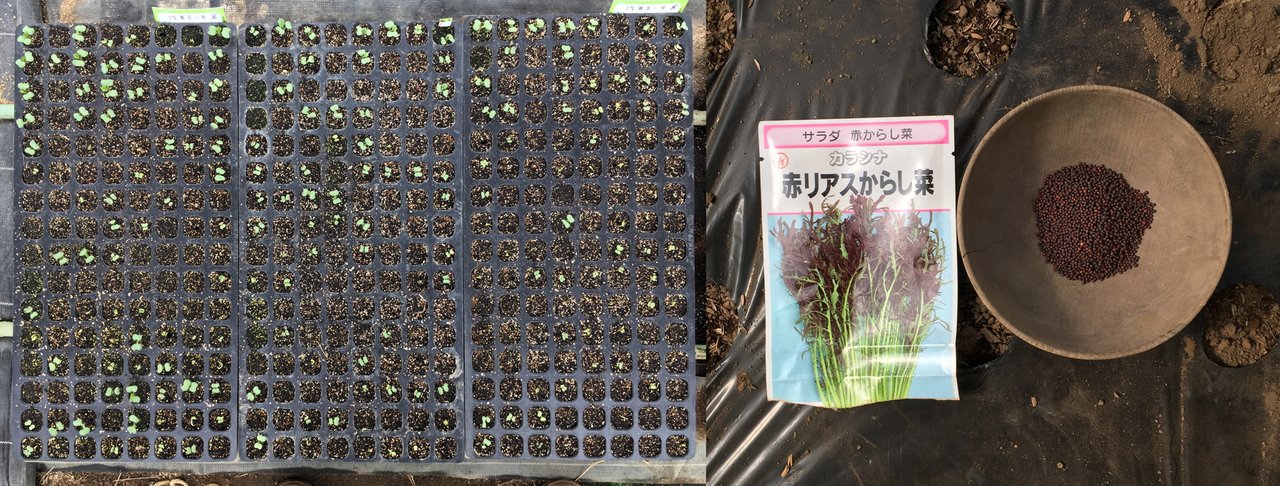

As an organic farmer from France -- where EU laws strictly define which vegetable varieties can be grown by organic farmers and ensure that all organic vegetables are grown from organic seed -- I assumed that self-styled organic farmers in Japan would be just as wary of non-organic seed as their counterparts in France. Here, too, I was wrong: of the half a dozen organic farmers I talked with and/or worked with, not one relied on organic seeds alone. In fact, I am not sure any of them used any certified organic seed at all. As well as not exactly helping the organic seed industry and -- in my opinion -- misleading the consumer who in buying organic produce likes to think it is 100% organic, I got the distinct impression that using non-organic seed was responsible many of the problems I saw farmers having in their nurseries (poor germination, poor resistance to disease etc.). After all, a seed produced by a plant trained to rely upon chemicals to survive cannot be expected to do well without the same chemical inputs. One farmer pointed out that seeds are stronger than we think -- a seed from a non-organic parent can survive on nothing more than organic fertilisers -- and that, at any rate, weeding out the weaker seeds was a way of producing stronger plants (those that survived that is): while I'm sure he is right, it does still seem a little unnecessary and irresponsible to not use organic seed. So, once again, seeing the effects of not doings thing a certain way helped me to appreciate the reasons for doing them that way in the first place.

Conclusion

All in all, then, looking back on my year as a farming apprentice in Japan, I do seem to have had to do an awful lot of things that went against what I had been taught previously and which I still believe to be both more economical and more ecological. However, as I was told by someone not to referred to above, the best apprentices (i.e. future farmers) often come from the worst farms: seeing things go badly all the time makes you think more than seeing them go well all the time (which leads to complacency), prepares you for the worst, and makes you stronger, enabling you to identify a problem from the very first signs. So I think I'll ponder on that while I prepare the next article in this series.

On rereading this article it occurred to that it could very well be taken as a totally negative experience. So, to balance things out, the next article will be on the subject of all the good stuff that happened whilst I was learning to farm the Japanese way. See you then!