「Dignity and the hive mind in science fiction and fantasy」

. . . practical thinking . . .

I write primarily fantasy and science fiction and there is a particular type of character that seems to be difficult to write. Not difficult because that type of character doesn't exist. None of them exist.

No, the substance of fantasy and science fiction is mere possibility, even impressive impossibility, but not existence. There must rather be entertainment, a hint of deeper meaning, and a great amount of sense of coherence. Existence — that has nothing to do with whether or not such characters are realistic characters to the mind of the reader. And what matters is only the mind of the reader.

So? There's a troubling issue in writing dialogue and description corresponding to a type of character whose psychology is basically a whorl for all we know. We have no idea about it, even though this type of characters appears frequently and often figures obtrusively in famous stories of these genres. It's the Hive Mind.

What exactly is that? I don't know. A unicorn is more comprehensible.

We can imagine a horse; we can imagine a horn. Therefore we can imagine a horse with a horn.

Maybe there is a faint smell of glue near this mythical beast. Apparently whether there is such an odor depends on whether the author set out to write hard fiction or not.

Pretty straightforward invention by pure combination. And what does the invented beast do? Probably it does whatever a horse does. But then it also does what a horned animal does.

If the writer puts that down the reader is persuaded the rules of the game were not violated; the reader is not fazed. The reader suspends disbelief and is not bothered out of this state. And then, all is well. The readers read on: Everything makes sense. It's not real, but it makes sense.

Good. Nothing more than that is required. The fact there are no such objects is not relevant.

The feeling of reality, that something is sensible, real, is merely that it is in that context as it is described to be (John Toohey, Reality and truth, Philosophical review, 48(5):492–505, 1939.9). This definition might be applied recursively to a description itself to see whether something, if not real and not actually sensed, is all the same realistic and appears sensible.

Floyd Allport (Institutional Behavior, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1933) writes: ``Only communion with whole individuals can make an individual whole.'' And here I suggest that only psychologically realistic characters interacting with psychologically realistic character can make each other realistic. I mean here to point at the apparent paradox that if a realistic character is made to interact with an unrealistic one in a story, that realistic character, too, appears sufficiently unrealistic. The whole story inherits the resulting unreality, is no longer as sensible, and it loses some dramatic power. It loses its hold over the reader.

People are genuinely interested in people. We are reading primarily for meaningful description of social interactions (Satoshi Kanazawa, The intelligence paradox, Hoboken: Wiley, 2011), and we're jarred, as readers, by having described to us, and presumably being asked to imagine, social interactions that lack a sense, a coherence. Kanazawa argues that none of us evolved to preconsciously (Lawrence Kubie, Neurotic distortion of the creative process, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1958) distinguish between realistic image or sound or description of social activity, because for millions of years, for our ancestors, there were no such things. A friendly face was a friendly face. The sensible appearance of something was that and nothing else. Preconsciously means we accept it for the moment, even if with some effort we can properly select from the resulting stream of apparently sensible events and analyze separate the real from the not real. (As will be discussed below, again, the combination of emotionally accepting, for the moment, the appearance of the negative and shocking thing as the thing itself, capturing and holding our attention, combined with the human possibility of such rational distancing and the feeling of safety, distance from the drama, makes the experience both attention grabbing and pleasant, and enables art appreciation. The lack of either one of these two primary factors is why art appreciation is not a trait of other species.)

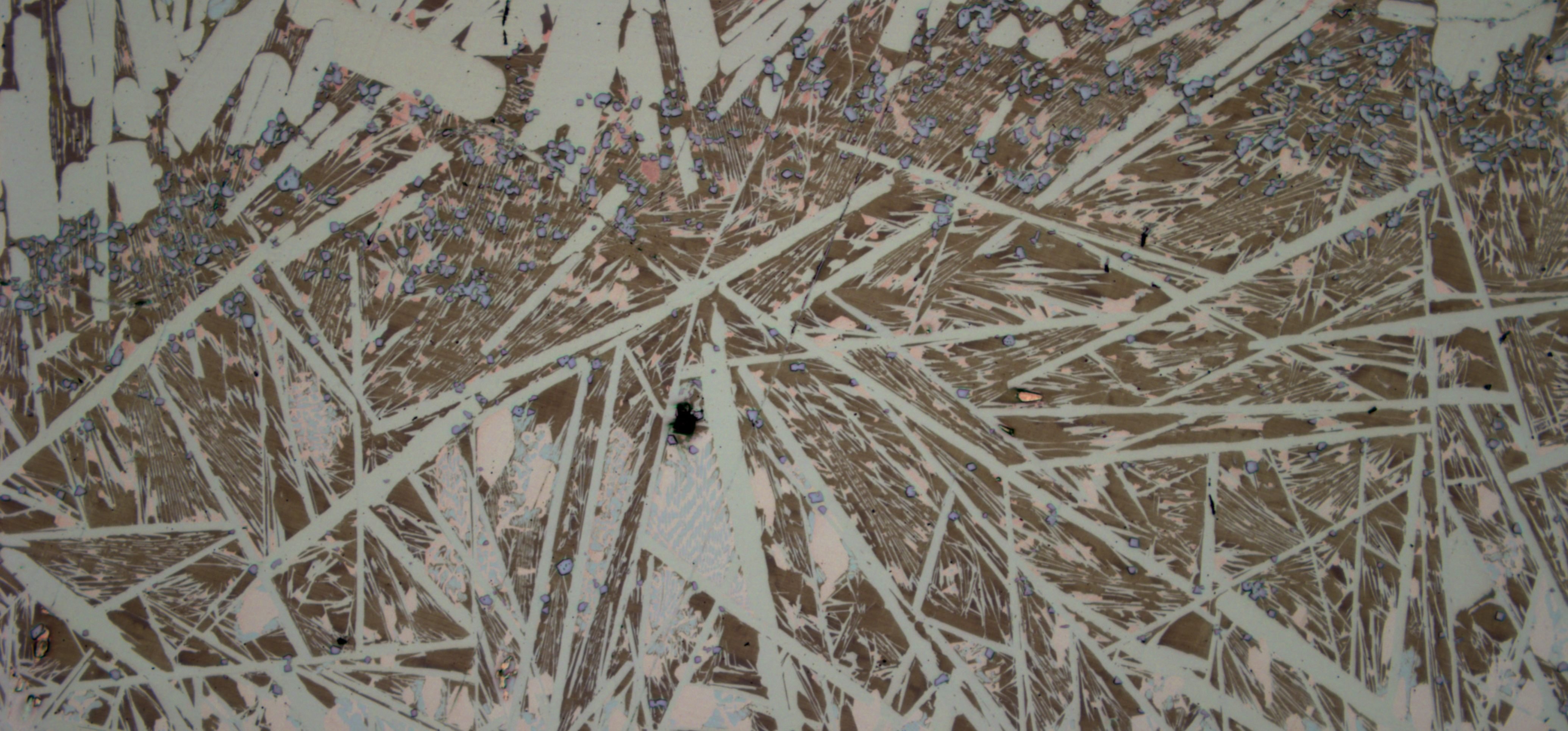

Nature up close . . . Nature is mostly order arising from disorder. That is true at the smallest scale. And true at the largest scale. Even in fiction, where characters interact in a disorderly natural way. The result is cohesive and sensible and convincing if they are the right characters participating in the right interactions, all in a messily but coherent way. The puzzle pieces fit even though they were apparently thrown together, pleasant surprise is preserved.

The reader wishes to read more.

(All this talk of realism is closely connected with our sense of fairness; something is fair when it's both valid and real. A test is fair, for example, when it gives the same result in the same circumstances, repeated, and actually tests that which it's described to test.)

Gregory Bateson (Human dignity and the varieties of civilization, Science, Philosophy, Religion, New York: Bryson Finkelstein, 1943) says :

When you ask him as an anthropologist to consider the words human dignity in the context of the various cultures and civilizations that exist in the past, present, or future, he must first pause and clarify what he or anybody means by the phrase human dignity. He next conjectures that ``some sort of acceptance of the self is not only a prerequisite of self respect but of mutual respect between two or more people''.

Bateson then conjectures which sequences of behavior in any population of interacting actors each tend to promote such generous self acceptance and corresponding outcomes :

``. . . those sequences of interpersonal behavior which increase the self respect of one participant without diminishing it in the others . . . and those general notions and presumptions about life which help us to see our own roles with self respect''.

I think some writers might see where I am going with these quotes.

When writing hive minds, as is common in science fiction, very few writers bother with any of this. And the characters thus described therefore appear to have very little dignity. That makes them replaceable — in other words, relatively uninteresting.

Some of the better hive mind descriptions in science fiction are found in, for example, The Santaroga Barrier (Frank Herbert, New York: Berkley Medallion, 1970). But otherwise typical hive mind characters . . . lack dignity . . . by the nature of the plot.

Bateson conjectures that, thanks to the ability of persons to shift their point of view, they can even view their self repudiation, in brackets, as part of a history, as part of their acceptance of their self, namely, their self as self repudiating, so the question of self acceptance on the whole is tied up with history of the person.

Which is the flaw most stories seem to make; their hive mind characters are often without any interesting history. Had they accepted their condition at the end of that, knowing that, they would accept their self, in a general sense, but that is rarely the case. The writer rarely provides them any good (I mean, interesting) reason for this decision, so they basically all appear as they are, slaves, and therefore undignified. Simply weak.

The typical reader subconsciously rejects this portrayal. (He doesn't want to read about weak characters, being likely weak himself. This is the reason superpower stories outsell literature of the same type in the same genre by tens of millions of copies. In such cases, the author is selling reader projection onto the character wish fulfillment.)

However, making up a history for every participant in a hive mind is a pain — which is probably why few writers do it. There is needed a generic way of suggesting such a history, in the sense of showing the tip of the iceberg to suggest the huge but unseen mass beneath it, without actually showing this mass. This is what Lion Feuchtwanger (Notes on the Historical Novel, Books Abroad, 22(4): 345–347), 1948.9) says.

Hints about such a history for the hive mind characters might be littered throughout the text.

「Distance and negative emotion and enjoyment」

. . . theoretical thinking . . .

Lion Feuchtwanger (The laurels and limitations of historical fiction, Detroit : Wayne State University Press, 1963) writes about historical fiction, but all of what he says transfers to fantasy and science fiction.

The reason is quite simple; in both genres we feel free to expose our most appealing and realistic characters to extreme situations and tensions, and then dress them up in the guise of far future or far past or even of a distant, different world, to constantly remind the reader that he is safe. There is attention grabbing negative emotion, yet constant preconscious and conscious reminder for the mind of the reader that while exploring possibly disturbing or disorienting environments, radically new environments, he is nowhere near and safe.

This produces pleasure and is a core of art appreciation. (Feuchtwanger, 1963 ; W. Menninghaus, V. Wagner, J. Hanich, E. Wassiliwizky, T. Jacobsen, S. Koelsch, The distancing embracing model of the enjoyment of negative emotions in art reception, Behavioral and brain sciences, E347.1–E347.63, 2017.2)

A similar reason exists for why middling novelty is most pleasant (Gerda Smets, Aesthetic judgment and arousal, Leuven: University Press, 1973).

The novelty is not comprehended and preconsciously appears as a source of possible pain and catches our attention, initiates cognition and an orienting reaction. But this novelty is not so great that is not comprehensible and actually causes any pain. We solve the puzzle, resolving the tension. Our brains reward ourselves.

Feuchtwanger, for yet again the same reason, argues that the great story begins neither with dialogue, nor thought, but with a gesture.

A gesture is somewhat ambiguous, and you must read on to gather the context and decipher what it meant.

The author is further inspired to develop a context . . .

「Sufficient detail」

. . . contextual thinking . . .

In the last chapter I informed you exactly when I was born

— but I did not inform you how.

No; that was reserved entirely for a chapter by itself.

--- Laurence Sterne, 1760, Tristram Shandy, vol. 1, cha. 5

You can write a twist in the style of of O Henry, omitting certain information, whose revelation changes the context and therefore the meaning of the story wherein it occurs, as Arthur Koestler explained, or you can follow Laurence Sterne in providing superfluous information that distracts from the twist in plain sight.

Ango Sakaguchi (Discussion; under the cherry blossoms in full bloom, The journal newsletter of the association of teachers of japanese, 3(3):3–21, 1966.4) says that we out strive to write as lightly as people really talk and think, like falling feathers, but equally real, it must hit hard. This is clearly demonstrated in many of his stories. There are often no twists. And none are needed.

However, maybe we'd like to create a surprise for the reader. What ought we do, then, if we also wish to write lightly and powerfully? Omit the relevant or supply in large doses the irrelevant? Simply write tersely and concisely? Is that required?

We should merely consider the entropy of what we write, I suggest. Writing simply does not mean producing short sentences or using short words or a limited vocabulary, I think.

You can write as much or as little as you want. What is required by the whole story to make it work is what you would write. Appropriate is whatever makes your literary trick work. Pick your favorite literary trick and write however much is then appropriate.

Rather you reduce the entropy of the text. One idea per sentence, one idea per paragraph. And one idea per section. Thus for each section.

You can keep score.

It's not hard to mentally calculate while you write.

Take the logarithm of the count of the ideas in each part at each level of your text and then add. Ideally you want the result to be as close to nil as you can make it. Logarithm of two is around point three. That of three is approximately half. And that of one is nil, and a vast sum of nothings is also nothing, which is what you want.

SO . . .

Let's try a writing exercise, how about it?

The first image is of waves breaking on a beach. In the distance is a steep cliff. Then jutting rocks in the sea. Farthest out are faint mountains beyond gentle tree covered slopes.

The second image is seaweed, I think.

The third image is a page of text composed with an attractive female face. There is a hole. The face shows unobstructed through the hole. Otherwise the text drapes over the face.

Let's apply the ideas in the essays above to a story we might write if we treat the three challenge themes as constraints about what we might write.

So we might first write a pitch for a story. This coarsely outlines the story.

Humans are mostly extinct. Artificial intelligences manages a city under the sea. The few surviving humans live amongst them and eat mushrooms and seaweed. Artificial intelligences each consist of a swarm of common bots. Each bot is characterized and named by a natural language Word. And these Words pass messages to each other, different combinations being the Minds of different Citizens. A pattern of Words in communication wirelessly controls various more or less automatic bodies. The bots therefore understand natural languages and the people and often think like people, with a few caveats. Something bad happens. The power goes out, and the place gets flooded.

Disaster fiction is always popular, so why not.

Let's see if we can't quickly write up a beginning that indicates somewhere for the story to go.

「The surface of a face」

Some things require an excuse. Or else they cannot be done. The rules of civilization are typically that excuse. Or they are a proper part of it.

1

Rain.

A wide avenue, many lanes, tall buildings on both sides, but no people. Just long, straight, black, empty pavement stretching far back and far ahead.

Ah! There is somebody. Far away. They appear tiny. A speck in a black uniform walking in the middle of the road.

Receding? Approaching? Unclear.

But anyway, it was not whom they were waiting for. Just one person. Somebody else.

A woman and three Indeterminates stood at one end of all the lanes.

The woman was rolling a black bead in her hand.

``Isabella . . . '' whined the doorguard.

``I know,'' she replied.

Her attention returned to the end, where they stood. At the edge of a sudden cliff.

She rolled threw the bead at the figure in the distance. It . . . did not get anywhere near where it was apparently intended. And it bounced . . . and she could no longer see it . . .

She turned. No more looking back. No more futile actions — only that last one.

``Isabella . . . ''

Isabella briefly glanced at the doorguard. She'd separated him from his favorite door, messaged him to retreat away from the portal.

He was one of three. They stood around her in defense against invisible enemies.

Why not. Her mind was the amalgamation of part of theirs. Moreover it was the Words the three presently had most in common among them.

Meanwhile she looked up, at the blinding yet soft light. At the rain coming down.

Was this really all under a million tons of saltwater? she thought. She suddently realized that she'd never seen the roof of the world. Never had that thought before.

An irritated part of Isabella automatically sent a signal to the weather maker in this chamber. The weather maker was in the chamber? Yes, if only because she was in the chamber. She had a few Words in common with the weather maker.

The rain was still coming down. But it now was lighter.

Minutes passed. She counted. *Where was the Other?''

It was a generic Word. Not a named one. And not merely a pattern, but a real Aristocrat. Therefore commanded a much larger team.

Isabella needed that team for what she planned.

Wind. Drizzle. Musky, humid air. Spires in the distance. (Uninhabited.) Purple mountains beyond that. Flat clouds above. Endless pit below, bridged by many walkways. Water to the left. A wall of water behind glass-stone bricks. The sea; the dark, empty sea. And to the right . . .

The cliff suddenly terminated in walkways and the walkways in the wall of the column. Nobody had tried to blend the city on the floating platform with the walkways.

There were portals at internvals leading to poorly illuminated, seemingly endless tunnels. Their walls, too, were basically transparent.

Somewhere in the distance, outside the main chamber, there was an elevator, exactly like the one that brought them here.

2

Contrary to the old saying, not all the serious, the dangerous, the important, the significant things happen quickly.

A slope may rise gently over enormous time and space. The result is a great mountain that mostly cuts off a whole civilization from another one.

Some things are dangerous not in spite of but because they happen slowly. This, too, has deeper meaning. It means, paradoxically, that a quick reaction is not always needed to some of the most dangerous and important events.

She threw glass at glass. It bounced off the speeding walls and landed right at her feet. She kicked it. It bounced off the walls and returned to her feet.

``. . .''

``34e4566ghkk38! What ar—''

``I'm bored,'' she declared. She was bored, and her brother had escaped into dreams, leaving his ten eyes vacantly staring at the dark water on the other side of the . . .

The column was transparent. Seaweed nearly as thick as trees, and stretching far higher than any trees that ever lived, rose around the column in weaving clumps green and vast.

No, the lift wasn't noiseless. It rose smoothly. But it wasn't noiseless.

An observer might argue regarding elevator technology. That it hadn't improved in a thousand years.

No, he'd be told. It hadn't improved in four thousand years. Because contrary the proud and false histories of the race, humans are not natural engineers.

They need pushing. And for a long time, that pushing was absent.

``More on that later — '' it was recorded in more recent histories. Except no recent history filled that promised section; they were all empty regarding the times of peace. Times which recent events suggested had ended. And all the historians were combinations of Words. None of them really existed as entities long enough for them to bother completing their works in progress, their records of events.

His buds shifted in his ears, and he winced.

The lift wasn't noiseless. Deep rumbling above and far below, and a sound like the grinding of gravel. And a faint whirring, and a hum that came and went.

This for hours. You see the tower was very, very tall. And in four thousand years elevators became more and more noisy, as people got rid of their ears. People became modular, before they mostly disappeared. The groups of Words and their drones were already modular to begin with.

Comforts were no longer prioritized. Rather discomforts were individually censored. It was easier.

Messaging mostly replaced hearing. It was bound to happen anyway. Some ancient writer by the name of Murakami had predicted this would happen. And it happened, and he, long dead, was therefore rewarded by the Administrative Committee with a small statue of himself in a park bench. For successful anticipation. Not that anybody other than bronze statues sat on the benches; they were traditional. The statue looking up at the artificial Sun, holding his ears detached in his hands, with a big grin.

The lift smoothly came to a halt. No lurch to awaken him. 34e4566ghkk38 nudged him. He woke. Pulled the buds out of his ears. Fuck. That was hell, he thought.

He was the rare human, a rare Fragile in a society of Robusts. And worse, he still had ears. His sister removed hers.

All the machinery in the place was loud. He often considered doing the same.

``Get up, shithead. Let's go. You lead.''

``No, you lead,'' he blurted. Then instantly he regretted it.

He'd revealed his lack of knowledge of the Corridors to the others in the party. The ones sent by the Word. Their employer.

``Joking, only joking. Follow me.'' He was contrite; he started walking.

In reality, he had no idea where he was going, and attended to the flicks of her eyes, which told him where to go.

But he had to pretend to be the leader here, that's what they agreed on.

They soon arrived by the portal to the city in the chamber.

I'll continue from here . . .

〈 PRACTICAL THINKING 〉

#creativity #fiction #writing #scifi #creative #shortfiction #novel

#thealliance #life #isleofwrite #writersblock

I usually write stories which are 10,000–25,000 words . . . 40–100 pages.

ABOUT ME

I'm a scientist who writes fantasy and science fiction under various names.

The magazines which I most recommend are: Compelling Science Fiction, the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and the Writers of the Future.

WISE GUYS — practical thinking

FISHING — thinking about tools and technology

TEA TIME — philosophy

BOOK RECOMMENDED — fiction and nonfiction reviewed

©2017 tibra.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This is a work of fiction. Events, names, places, characters are either imagined or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to real events or persons or places is coincidental . . . Illustrations, Images: tibra.