In 1993, Robyn Miller and his brother Rand released Myst, a first-person adventure that would take the computer gaming world by storm. Myst’s amazing graphics, complex puzzles and richly detailed world saw it become the best-selling PC game to date, an honor it would hold for a staggering ten years. I caught up with Robyn to discuss his early days in the gaming world, time spent working with his brother, Myst’s many impacts on their lives, and more.

"Blurry retouched Robyn: no age spots, no nose hairs, and no wrinkles." View full size.

So to kick this off, maybe you could please give us a rundown about your early background, how you got into computers and then into playing and eventually making computer games.

Robyn: Yeah, so it’s interesting now because I’ve been working with computers for so long that there really is a large history for me, and time has passed by quickly, it seems. I began seriously working with Macintoshes I guess about 1985 and 1986, and that’s when my brother Rand sent me a copy of HyperCard. HyperCard was something which came before the Internet – in some ways it was the Internet without the ability to connect to other users. It existed on your own computer and you could link from one page to the other via hyperlinks. It had a lot of the same or similar tools that the Internet has, but it just sat there on your own machine.

"This is Robyn, age nine, being treated like royalty as the Miller family arrives in Honolulu Hawaii. Less than a year later they will move away." View full size.

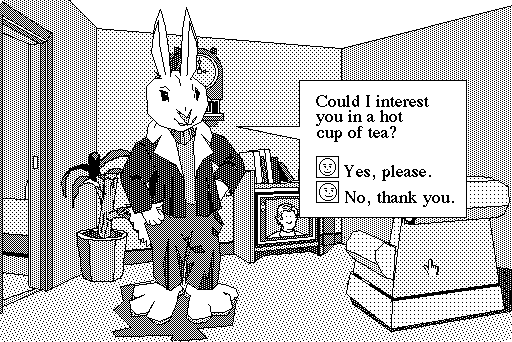

And so this arrived and I put it on to, well, not even my own computer because I didn’t have a computer at that point in time. I used my parents computer which sat in the basement at their house. I started playing with it and the first day I drew a picture of a manhole. I have no idea why I drew a manhole – I was living in Seattle at the time and I think I was just observing and examining the different kinds of manhole styles that were in the Seattle area. After I drew that manhole cover, I just was curious like “what’s under that manhole cover?” and what began to evolve was a world – a very primitive sort of world.

The Manhole, 1988.

So I made the manhole cover slide open and a beanstalk grew out of it, and in a fairly quick amount of time I created a series of cards... basically a slideshow that allowed the user to click on the manhole and go to the world at the top, where they could wander around. And you know, I didn’t really make any of this for anyone else to see. I made all of this just because I was curious how the tool worked, and it was just an experimentation as I was learning HyperCard.

I started to send the beginnings of this first project to Rand and he started to get very excited about it, which of course excited me, and I began to draw more and more of this world. Then I drew characters, and they were crudely animated. Then we came up with the idea to make this into a project, and it only took about a month and we turned it into a commercial product. We finished off the rough edges and so what I was initially made just by playing around and experimenting, we ended up creating a world where you could fully explore and get back to where you started. It was a complete world, I should say, rather than just a partial world. I would create on floppies – it was all on floppies back then – and I would send floppy after floppy after floppy down to my brother! He would clean up all of my work, because I was so new to HyperCard that everything I was doing was so messy. If you had looked at any of the scripting I had done, or even the way I had set up the cards, it was just such a mess! He would take all that and clean it up and turn it into something we could actually sell.

The Manhole, 1988.

After we had done that, he added some voices, and we took it to a HyperCard expo in San Francisco. We just thought, well, what the heck... let’s just do this, take it down there and show it off to a few people and see what happens. And it surprised us – we couldn’t believe it. There wasn’t much for HyperCard at that point and so people were really excited. In fact, articles were written which called it one of the hits of the expo, and I think that was because it was an entertainment product. No one knew what to do with something like HyperCard, and hey, if you think of it like the web, or at least when the web came out, broadly speaking, nobody knew what to do with it. It was very similar to that. We just turned around almost as soon as we got our hands on it and made one of the first entertainment products for it and people really responded to that in a positive manner. So, as a result of that, we had some offers from publishers.

The Manhole, 1988.

Could you maybe go into details of who they were and what they offered you?

Robyn: I can’t remember who all the publishers were, but the one we were happiest about was Activision. They came to us and they offered us a deal, and we were really flattered that any publishers were willing to offer us a deal for this thing because we never imagined that we’d be making video games. I certainly didn’t imagine that – I was going to the University of Washington getting a degree in anthropology, and this was the last thing I’d ever imagined I’d end up doing. Still, I loved doing it. I always loved doing art – art was something I’d had a passion in since my youth, so suddenly to have an entire project where I’d just drawn pictures and then have this idea that, wow, I could possibly do this for a living was pretty unbelievable to me.

I imagine it must have been quite dreamlike, especially with it being at the time such a new way to tell a story or such a new way to have somebody navigate through an imagined area. That must have been amazing for you?

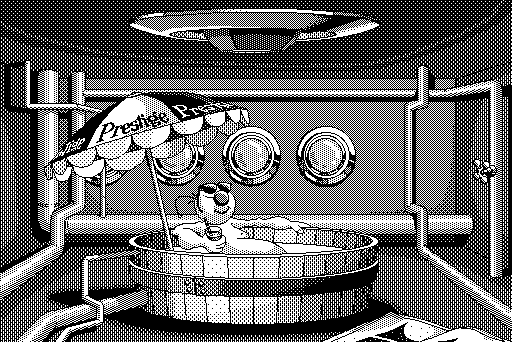

Robyn: Right, and before this I had been doing a lot of freelance work on the Macintosh for people doing design and illustration and I was head over heels with the Mac and the operating system and the tools I used. And with this I saw an opportunity to use it all the time, so we made this black and white version of The Manhole, just 1-bit on the Mac, and if you look at it now, well, it looks pretty awful… I think most people would think that! (laughs) Still, it has its charms. I don’t remember who made the DOS version, but I do remember thinking it was garish and I think it’s been long enough that I can say that! (laughs) But anyway, we came out with Cosmic Osmo and the Worlds Beyond the Mackerel while we were with Activision, and it was really amazing because I was almost graduated from the University of Washington and was like, “OK, I’m just going to start making these videogames” and so Rand and I worked on Cosmic Osmo and it was phenomenal!

Cosmic Osmo and the Worlds Beyond the Mackerel, 1989

Nobody was really making games back then – I mean, obviously there were, but compared to today, it was a very small community of people making games. We were so privileged and fortunate to be able to be doing that back then, and I think of course that part of the difference is because of the Internet. Now if you make a game you can publish it yourself online, but if you made a game back then it had to be packaged and sold in boxes by a distributor who had a sales team and a PR force behind it. It was amazing that we had a distributor that had picked up our games, and that was a great thing for us. So we did The Manhole and what most people have forgotten or don’t realize is that we had another, larger version which had this whole soundtrack which we did while we were with Brøderbund.

Cosmic Osmo and the Worlds Beyond the Mackerel, 1989

After that we did a small version of Cosmic Osmo, but then we did a massive version of it too. It was like twice the size of the universe of Cosmic Osmo – it was gigantic, and I don’t know why we did it! (laughs) The first version was on floppies, and it was fairly small and compact. And then for CD-ROMs we expanded the universe more than twice the size, added a soundtrack with music throughout the universe and really just made a very large version of the project. Now when I go back and wander through this world, it’s kind of hard for me to believe that I drew every single one of these images… it’s crazy! (laughs) A little insanity – but we had a ton of fun working on it. Rand and I were sitting in a room working on it and would just throw ideas back and forth and as we worked through them, we’d create it. We’d be like, “well what about this room?” and we’d create it, and then we’d say, “well what about an electric eel on that side of the room?” and then I’d just draw it. He’d be working on programming, and it was just a great work environment – probably the ideal working environment.

What was it about working with your brother that made it so great?

Robyn: It’s funny… I still remember that as my favorite working environment. It was literally a dump of an apartment, (laughing) we had no money, we had no guarantee that the project was going to make money and in fact it didn’t make any money, but we had so much fun creating. The value in anything you do is in the making of it and the creating of it, and it was a wonderful, precious time together. The fact that we were brothers made that time so much more precious and valuable – and we do speak a common language because we’re brothers and we’d spent so many years together growing up, and we see things a certain way – in a very similar way – and approach problems in a similar way too. So that Cosmic Osmo project was the first time that started to play out and we really started to see eye to eye and work through problems in a similar way. That project, spending hours and hours in the same room, was probably the first time where our relationship was working so much to our benefit to create something good.

And for how long was it just you two working together? I know you had someone else help out with the music at some point, right?

Robyn: I did music for Cosmic Osmo, and we had somebody else, a good friend of ours named Shep Lovick, who wrote some of the music. Plus, we did some of the music production at a studio in Texas. We had some instrumentalists play some of the tracks, but for the most part, the creation of the world, the sound effects and the day-to-day design, world creation and character creation, that was Rand and I, for 95% of the project.

Spelunx and the Caves of Mr. Seudo, 1991

When did that change – when did you have to grow the team?

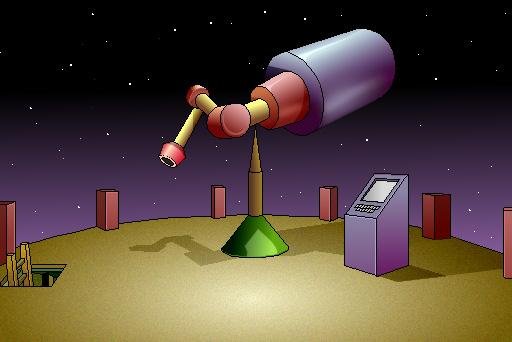

Robyn: Well, after Cosmic Osmo we did Spelunx, which was again just the two of us, and after that came Myst. And Myst was the project where we hired some other people, such as Chuck Carter, an incredibly talented artist, who was working in Spokane, Washington, where we were located at the time. We were lucky that he was there and that we got in contact with him. So for Myst, we had about four people. During the beginning of that game, I think there was a time where Rand and I were similarly in a room just designing the game, similarly batting ideas back and forth, creating all of the concepts and ideas for the game. Now, throughout the entire project we were not in the same room, but we continued to evolve the design for the game and stay in close communication throughout it.

Spelunx and the Caves of Mr. Seudo, 1991

Could you also please talk a bit about how you went from a point where you were this small team that made a few games, and then suddenly your fourth project was the best-selling PC game until The Sims. That’s such a massive achievement – I mean, here we are 25 years later and some guy is asking you about this thing you made in the early 90s. It was such an industry-changing thing, so how has that success sat with you? I think it’s interesting because you’re in this unique position where you’ve been able to follow, mostly thanks to the Internet, the persisting interest in your creation, see how it has touched lives, created fans and so on. You’re able to witness first-hand the effects of the fruits of your labour, as it were.

Robyn: Yeah, I mean, I think it has impacted me in many ways – some that are too complex for even me to know. But absolutely, and not just from seeing its impact in other games. I can’t tell you how many people have come up to me and said, “I got into my career because of your game” and every time that happens, I’m kind of astonished. In my whole life I never expected even one person to tell me that, and now I have heard it from so many people. Then there’s also – and this is what really freaks me out – when I hear, “oh, my fiancé and I played that and it had a huge impact on our relationship” – things like that. Or, “I played Myst with my father when I was at such and such an age, and it brought us closer together and was such a wonderful time”. So it’s these that I think are important and great things.

Myst, 1993

It’s a significance that goes beyond the commercial success, to where it’s touched someone in a personal way. A relationship between a husband and wife, or a special time between a father and child, to know that your project had that impact must feel absolutely amazing?

Robyn: Exactly – I see that it’s had such an impact, not only in people’s lives, but it’s also become a part of pop culture! It’s become this entity that’s larger than life, larger than this little game we made. You know, we were just making a series of games. We’d made The Manhole, and Cosmic Osmo, and we made Spelunx, and then we made Myst. Now, we knew Myst was better than those other games, we knew it was aimed at adults, but we never knew it was going to be this thing!

Myst, 1993

You weren’t designing a game for the Museum of Modern Art!

Robyn: Right! (laughs) We weren’t designing a game that was going to be there 20 years later and have people talking about it 20 years later. The same thing that happened to the other games was going to happen to Myst, you know? It was going to vanish after a while, maybe make its money back, hopefully, but the fact that Myst has had such a monumental impact is pretty phenomenal and remarkable. It still blows me away to this day. And I’ve not even mentioned the money it made, and the fact that it was such a hit game, and so many people played it. The sheer numbers of that… when that first happened, it just threw me for a loop. It didn’t even seem real. It was surreal, and I think I have a hard time grasping it even to this day! (laughs)

That wraps up the first of this two-parter interview – the conclusion is up next, in which we talk TV shows, The Immortal Augustus Gladstone, and much more. A big thank you to Robyn Miller for his participation. You can learn more about Robyn and his work at www.robynmiller.net, or follow him on Twitter.

Next:

Interesting People #3: Robyn Miller on filmmaking, character writing, videogames and more

Previous:

Interesting People #1: Chris Avellone on Pathfinder: Kingmaker