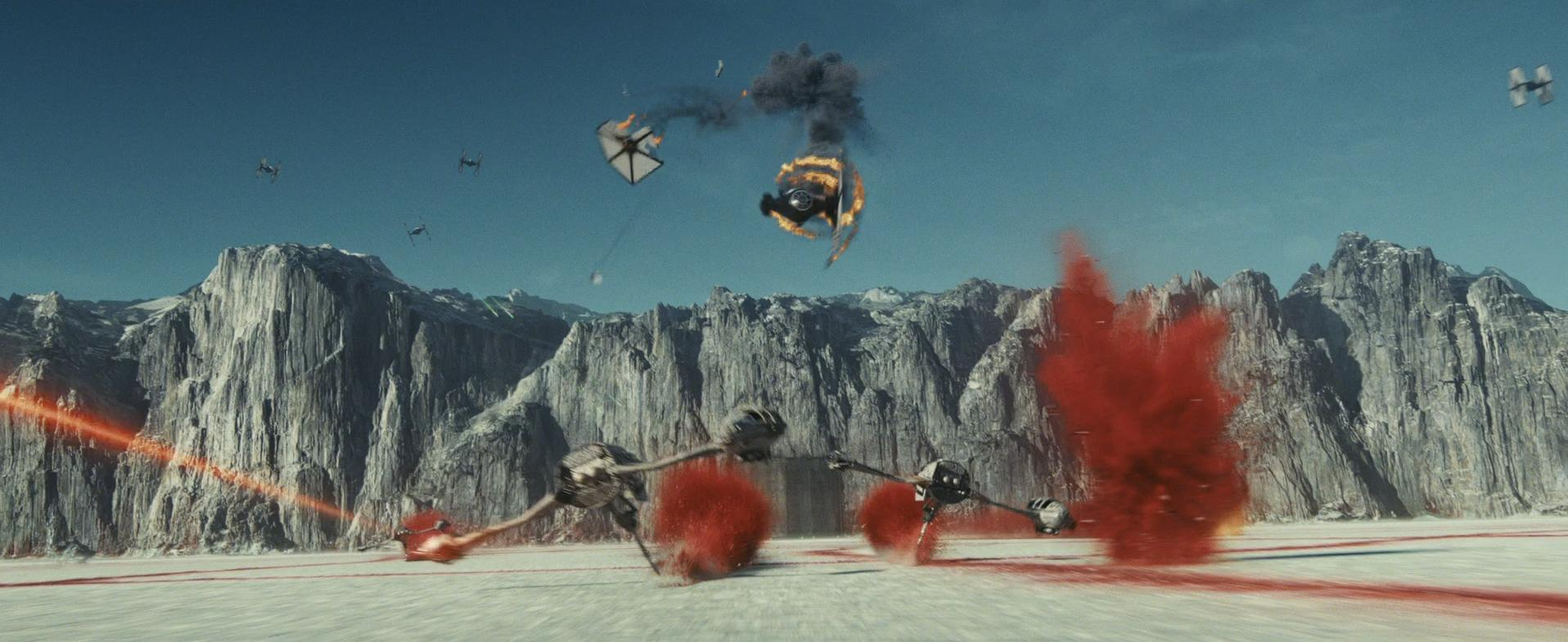

Movies are notoriously bad at getting science right. Star Wars is a notorious offender, especially when it comes to geology- which I've written about before. I love Star Wars, but they just never get the geology right. Crait, from the Last Jedi, might be my favorite Star Wars planet ever- but does it make sense geologically?

The filming location of The Last Jedi, the Salar de Uyuni in Bolivia, is the world's largest salt flat, dwarfing the salt flats in Utah. It's a harsh environment, to be sure- in fact, I'm going to include it in my Most Hellish Places on Earth series, so this post serves a double role. The ground is literally covered in salt- no plants can survive there, and no animals can live there year round. It is, for the most part, as dead as either of the first two entries in that series.

The Salar de Uynui, where the Crait scenes in The Last Jedi were filmed. [Image source]

The Salar de Uyuni is also incredibly flat. In fact, it's the single flattest place on Earth. And though you'd think it would be found in some lowland, it's actually in the Andes Mountains. And while it's dry as a bone all summer, during the rainy season the entire salt flat is covered by a thin layer of water, creating some truly bizarre visual effects.

Salar de Uyuni during rainy season. [Image source]

Salar de Uyuni, however, is different from Crait in several key regards. Most importantly, there's no red layer underneath Salar de Uyuni's surface. Instead, there's a layer of brine saturated sediment below the crust. This brine is actually economically valuable- there are large quantities of lithium in the salt of Salar de Uyuni, and it's most easily extracted from the brine. In fact, as much as 40% of the world's lithium reserves are found there. The sodium itself of the salt is also valuable, and potassium, lithium, borax, and magnesium are also present.

Below the surface of the Salar de Uyuni. [Image source]

So is the red stuff beneath the crust of Crait's salt flats possible? In fact, yes, it very much is. There's a type of salt known as sylvite that is that exact shade of red. Instead of sodium chloride, the salt we use most often, sylvite is potassium chloride. It's an isomorph of sodium chloride, however- they have the exact same crystal structure. Could the salt be deposited in the two layers like that?

In order to understand that, we've got to understand how salt flats form. Essentially, they occur when lakes evaporate away, leaving the salt present in all water to crystallize out. As more and more water evaporates, the remaining water gets saltier, and the salt crystals begin to form. This process doesn't work if the lake drains- only if it evaporates.

Sylvite. [Image source]

Because of this, it turns out that there are actually a few ways the red and white layers could occur. One likely scenario involves simply different dissolved minerals and water chemistry than occur on Earth. It's also possible there's something in the atmosphere leaching potassium but not sodium out of the surface. Or the red stuff might not be sylvite at all- maybe it was salt dyed red by some sort of algae or bacteria, which could no longer reproduce once the water got salty enough, so the upper layer of salt formed without them. Or it could just be a bright red soil, with only the top white layer being salt. Heck, it could even be radiation damage, which can change the color of salt, and then had more salt recrystallize atop it. It's somewhat hard to know which of these it is without actually getting to investigate the geology of Crait firsthand.

So the red-under-white salt plains of Crait work just fine geologically, it turns out! And the crystal filled caverns? Well, assuming they're salt crystals, that works just fine. Even more possible, they might be gypsum crystals, like in the Cave of the Crystals in Mexico. Gypsum crystals, like salt crystals, are evaporites. (Evaporation generated minerals.)

Another view of the Salar de Uyuni. [Image source]

All this brings up an interesting question, however- in order to produce this many evaporites across, presumably, an entire planet (because all Star Wars planets have only one type of terrain, for some reason), something had to happen to this planet's water. It all had to evaporate somewhere. We know there are still some small oceans- they're visible from space, and some of the canon extended universe material mentions that the Rebel base is on the northern continent. The most likely solution? Crait was a world of widespread seas, and is in the middle of a SEVERE ice age, and most of the water is locked up at the poles in enormous ice caps, greatly reducing the range of the seas. Alternatively, if the red layer is made up of salt crystals reddened due to radiation damage, Crait might have been subjected to some apocalyptic stellar event that stripped away much of the planet's water.

Final verdict? Crait's entirely geologically possible! And heck, it's not the only one, either- all the other planets are geologically entirely possible. Luke's planet with the islands (assuming there are some larger ones somewhere, it works), Canto Bight, and the lush rebel planet from the beginning are all perfectly geologically plausible. There aren't really a lot of other geologically plausible planets in the series, so I'm really impressed. Yet another reason why I'm a fan of The Last Jedi!

Bibliography:

Star Wars: The Last Jedi

http://starwars.wikia.com/wiki/Crait

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salar_de_Uyuni

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sylvite

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salt_pan_(geology)

http://www.adventuresinpoortaste.com/2017/12/15/reality-check-geology-of-star-wars-the-last-jedis-planet-crait/

https://earther.com/the-amazing-earth-science-behind-the-last-jedis-new-min-1821429894