By Jake Brukhman (@jbrukh). Cross-posted from the CoinFund Blog at http://blog.coinfund.io.

This piece assumes some general familiarity with the blockchain technology space. If you would like an introduction to the technology that underpins Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, see this article on Re/code.

Ever since launching CoinFund in July of 2015, I’ve been viewing the blockchain technology space from the point of view of an engineer and a portfolio manager. I’ve been thinking, therefore, about how to explain the blockchain technology space to traditional investors in traditional terms. What makes blockchain companies unique and interesting opportunities in the investment landscape?

To see the potential long-term implications of this fascinating space, one needs to take in a thirty minute primer of technical details — What is a blockchain? What is interesting about decentralization and trustlessness? What’s the deal with smart contracts? In a semi-technical crowd, the audience is quickly lost in jargon and a technologist’s reasoning.

Instead, I think the correct way to present the blockchain opportunity to traditional investors is through the lens of growth investments — yesterday, today, and tomorrow. It is a story of a technology that democratizes, opens, and optimizes a difficult investment environment.

Where is the capital?

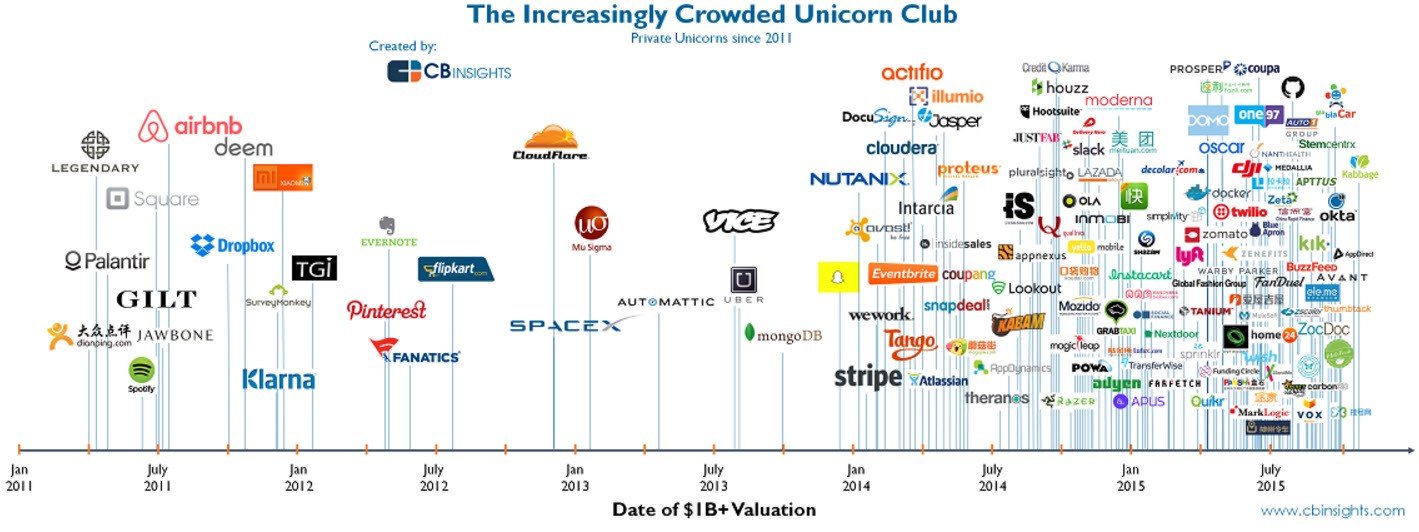

For the last 15 to 20 years, startups have proliferated in the market across all verticals. You have ZocDoc for doctors, UpCounsel for lawyers, Seamless for food delivery, Tinder for dating, and on and on. Just about every New York University junior one meets is trying to either be CEO to or a VC in the next “Uber for X”. Take a look at this chart in which you can witness the staggering “unicorn density” of our time:

As more companies take up the startup model, there are more and more private companies and fewer and fewer public ones. Just a few metrics paint a clear picture. The number of firms on the U.S. stock market started declining in the mid-1990s from a high of about 7,300 listed companies. By 2015, after a lazy uptick, there were only 3,700 left. Startups, pumped by high valuations and VC capital and a tech entrepreneurial culture, stay private longer in a “psychological shift” which has been described as “Silicon Valley’s distaste for the IPO”. Between 1996 and 2014, the average time to IPO went up from 3.5 years to 6.9, according to the 2015 IPO report by WilmerHale. And most recently, the number of IPOs has been dropping globally, with the tech sector leading the way. A 58% drop in NYSE IPOs in 3Q15 YTD compared with the previous year was accompanied by a 77% drop in dollars raised, according to Ernst & Young.

In short, capital is moving from the public into the private markets for the world’s primary growth sector — technology. According to Rett Wallace’s assessment of the tech bubble, “27 times more primary capital has gone into U.S. technology companies privately than publicly. And if Box.com had actually gotten its IPO done on schedule last year, it would be 88 times more.”

In such an environment, what does participating in the growth sector look like for investors?

Growth investments yesterday and today

the turn of this century, investing in growth would looked like this:

Joe the Investor would identify tech as a growth sector. He would send some cash over to his Ameritrade account, and — this being 2004 — buy some Google at the IPO. Then Joe would hold Google for 10 years. In the interim, Joe would know that he could dump some of his Google stock if technology took a downturn. Finally, Joe would sell Google in 2014 for a 12x return.

And here is what growth investment looks like today:

Spencer is a private investor. He has a top 1% salary and therefore qualifies as an accredited investor, which allows him to participate in private offerings. In 2009, Spencer would notice a company called Uber doing a funding round on AngelList. Spencer’s contacts on AngelList are investing, so he would decide to follow suit. It’s not likely that these investors would be able to predict that Uber would take off, create a new industry, and become one of the greatest growth companies of all time — it’s not likely that Uber could predict that in 2009. Following his investment, Spencer is stuck in Uber private equity for 7 years with very limited options to take profits before a liquidity event.

Perhaps next year Travis Kalanick will decide to take Uber public, but no one can be sure. If he does, Spencer will make a 12,700x return.

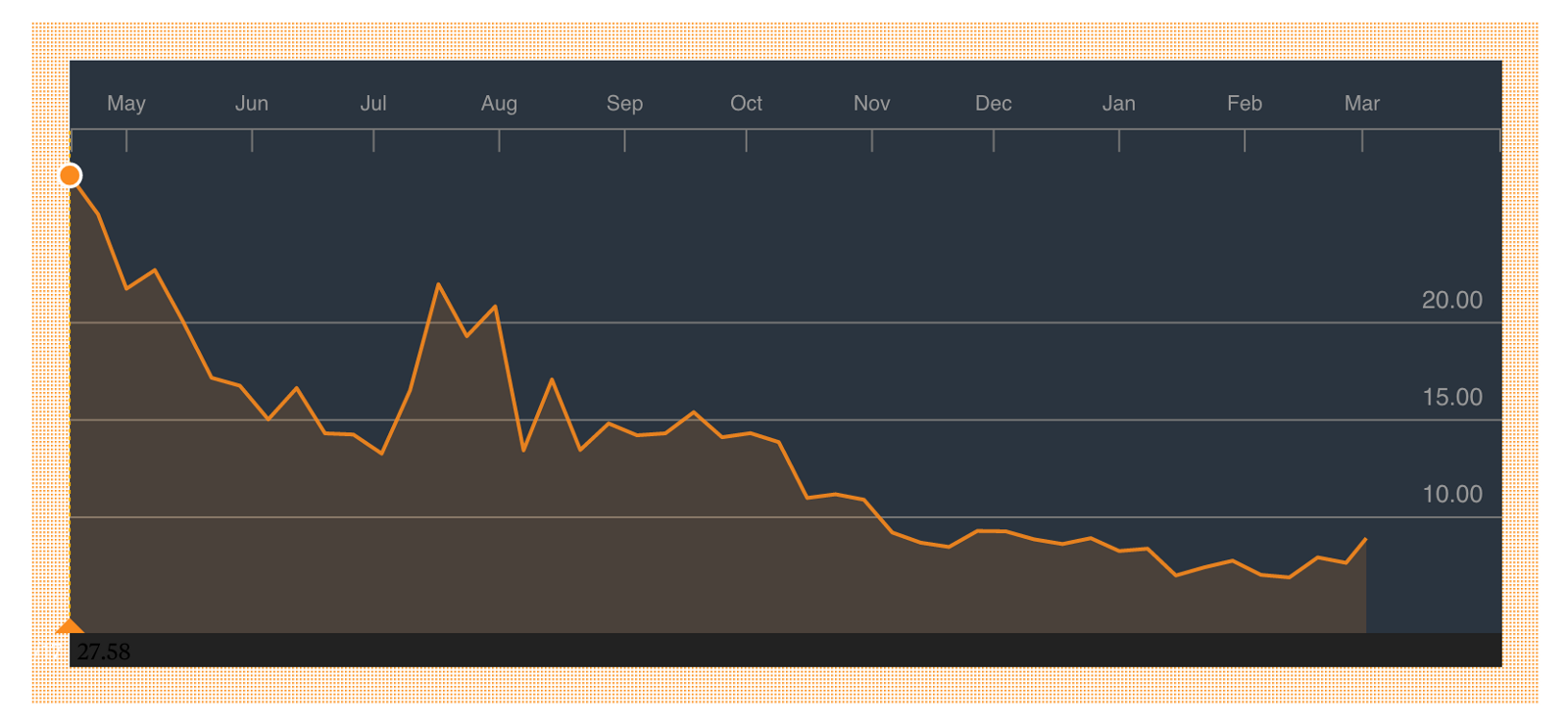

When growth companies move into the private sector, traditional public investors are left with little access to growth and a precarious stock market. “Growth and value investing” seems now a fragment of the past. And even when startups do IPO, overvaluations often foil performance in the public markets. To cite [some recent examples](some recent examples), Box stock fell 30% shortly after trading. The beloved Etsy fell 70%. At the time of the IPO, it is simply too late for public investors to participate in the growth of startups.

It would appear that in this regime the privilege of private investments goes to affluent individuals. Yet, while accredited investors have much greater access to outsized returns, their investment landscape is far from rosy. First, there is little data, research, or transparency in the private markets. A hedge fund trader might receive an offer to buy Lyft stock, but how does he judge whether it is a good one? Virtually all ridesharing competitors today are in the private sector and are thus tight-lipped about basic metrics such as revenues and customer acquisition costs — basic parameters that have been traditionally used to price stocks. Once again, this kind of uncertainty contributes to overvaluation and only when the company eventually reaches the public market do valuations start to deflate back to reality.

Finally, it goes without saying that the lack of liquidity for private investors is a long-standing issue. But with the advent of efficient new trading technologies and a global market, low liquidity might become a concern of the past.

Blockchain companies are models for the growth investments of the future

blockchain company is a special species of technology startup, one where its business gives it a distinct advantage in its own business operations. It’s kind of meta, but consider that Apple’s expenditure on its internal hardware is probably much less than Google’s — Apple manufactures computers and has vast economies of scale on hardware; or that it costs Twilio much less to send a text message compared to a startup who has to use Twilio to do the same.

Just like tech startups need computers, they also need funding. And blockchain technology companies happen to be in a unique position to fund themselves because their product is highly conducive to transferring currency-like and stock-like assets between investors, entrepreneurs, and even digital organizations.

In practice, the prevalent method of funding blockchain companies in recent memory has been the “crowdsale”— where the company sells its own cryptocurrency, cryptoequity, or cryptotoken to the public before the system is built and then uses the funds as a seed investment. When the blockchain finally launches, the stake becomes tradable and liquid and early investors stand to make a good return — in effect, the blockchain company has done an IPO that lies outside the traditional financial system.

The Ethereum crowdsale is today the fifth largest crowdfunding in the history of the planet, having raised $18M against a whitepaper written by a gifted 20-year-old college dropout. Having used the funds to build a complex organization with tens of employees and many more in distributed projects from all over the world, and against non-trivial amounts of negative social pressure from the cryptocurrency community, Ethereum was released as a public blockchain a year and a half later. In 2016, Ethereum grew in price by a factor of 10, and became the world’s second largest cryptocurrency by market capitalization.

Such an “initial cryptocurrency offering”, or ICO, has a highly favorable character for investors:

First, the ICO is available globally to all investors, and in most jurisdictions there are compatible regulations that allows participation. The disparity between Joe and Spencer investors that we see in private equity on the traditional markets has been reduced, if not eliminated.

It is an equity crowdfunding, so the market can potentially accommodate large raises — a boon for companies. Even in traditional markets, we have begun to recognize the value of equity crowdfunding with the JOBS Act and the proliferation of platforms like Crowdfunder and CircleUp, with this high-growth market estimated to reach nearly $100 billion ten years from now.

Unlike typical private companies, blockchain projects often adopt an open source or open community model, so development and performance metrics are available and transparent. Unlike in speculative cryptocurrencies like bitcoin, cryptoequity investments often lend themselves to straightforward modeling, as they are based on a well-defined business product proposals: if the platform acquires n customers, it will generate r returns.

Liquidity is one of the foremost considerations in an investment. Most ICO investments become liquid at beta, and investors only have to wait out development time (compare with Uber, above). Not only is liquidity often available over the counter during this period, but the advent of smart contracts will send the wait period to zero: you will soon be able to trade cryptoequity immediately after purchasing it at crowdsale using a decentralized exchange.

Blockchains facilitate the low-cost, fast, and efficient transfer of equity between stakeholders. This is a vast improvement of the stagnating, expensive, and slow process of paper deals on the private markets.

It’s easy to see that with these favorable characteristics, ICOs have the character of the kind of high-tech and low-friction applications that we’ve become accustomed to over the last 20 years and stand as a open and efficient model of how growth investing could be in the future.

Jake Brukhman is a co-founder @ CoinFund, a diversified portfolio that tracks the technology space. Follow us on Twitter @coinfund_io or join our Slack community at http://slack.coinfund.io.