In 1901, there were more deaf players on Major League Baseball teams than there have been in the 116 years since that time. They strongly influenced the game at the beginning of the 20th century, which I learned more about from reading the book Havana Heat by Darrell Brock. Strangely, very few deaf players have played baseball at that level in the years since, leaving questions about why their impact peaked and then fell.

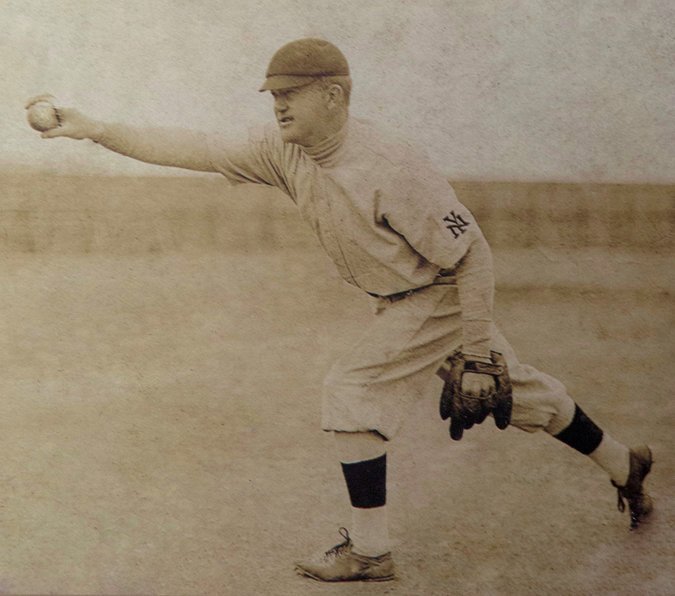

An artist's depiction of William Hoy, one of the first and best deaf players in the major leagues. (8)

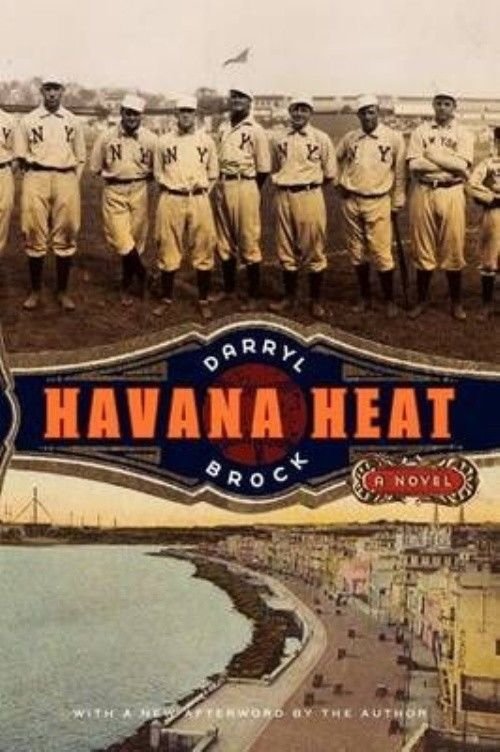

Cover of Havana Heat book.

Havana Heat is a novel that follows a portion of the life of Luther Taylor, one of the greatest deaf-mute athletes of all time. He was a pitcher for the New York Giants at the peak of their glory years, helping them win two league pennants and the 1905 championship. Brock’s story fictionalizes a trip that Taylor (probably never) took with the team to Havana, Cuba, in which he met and helped a deaf boy in Cuba. It’s a good book for a lot of reasons, but I am most thankful for the way that it illuminates the contributions of these deaf athletes of the early 1900s. You can call me a lifetime baseball fan and a student of history, but I would never have known about these players if not for Brock’s book. (1)

Baseball for Dummies

Around the turn of the century, as baseball’s popularity grew in the United States, there were a number of deaf athletes on big league teams. Nicknames have always been a big part of the sport and back then, they were used to typecast certain players. As Brock’s book points out, left-handed pitchers often were nicknamed “Lefty”, short players were called “Shorty”, German players were “Dutch”, and deaf players all carried the nickname “Dummy”.

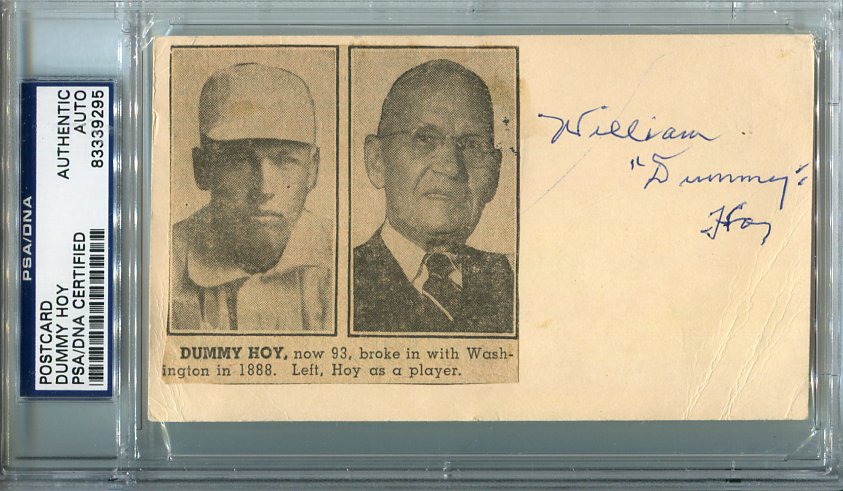

The two most successful deaf players of that era were William “Dummy” Hoy and Luther “Dummy” Taylor. The nickname seems quite derogatory to us today, since deaf people are not stupid. They lack the sense of hearing that many of us take for granted. But Hoy and Taylor chose not to fight their nickname. Instead, they used it as motivation to work harder and show the world what they could accomplish.

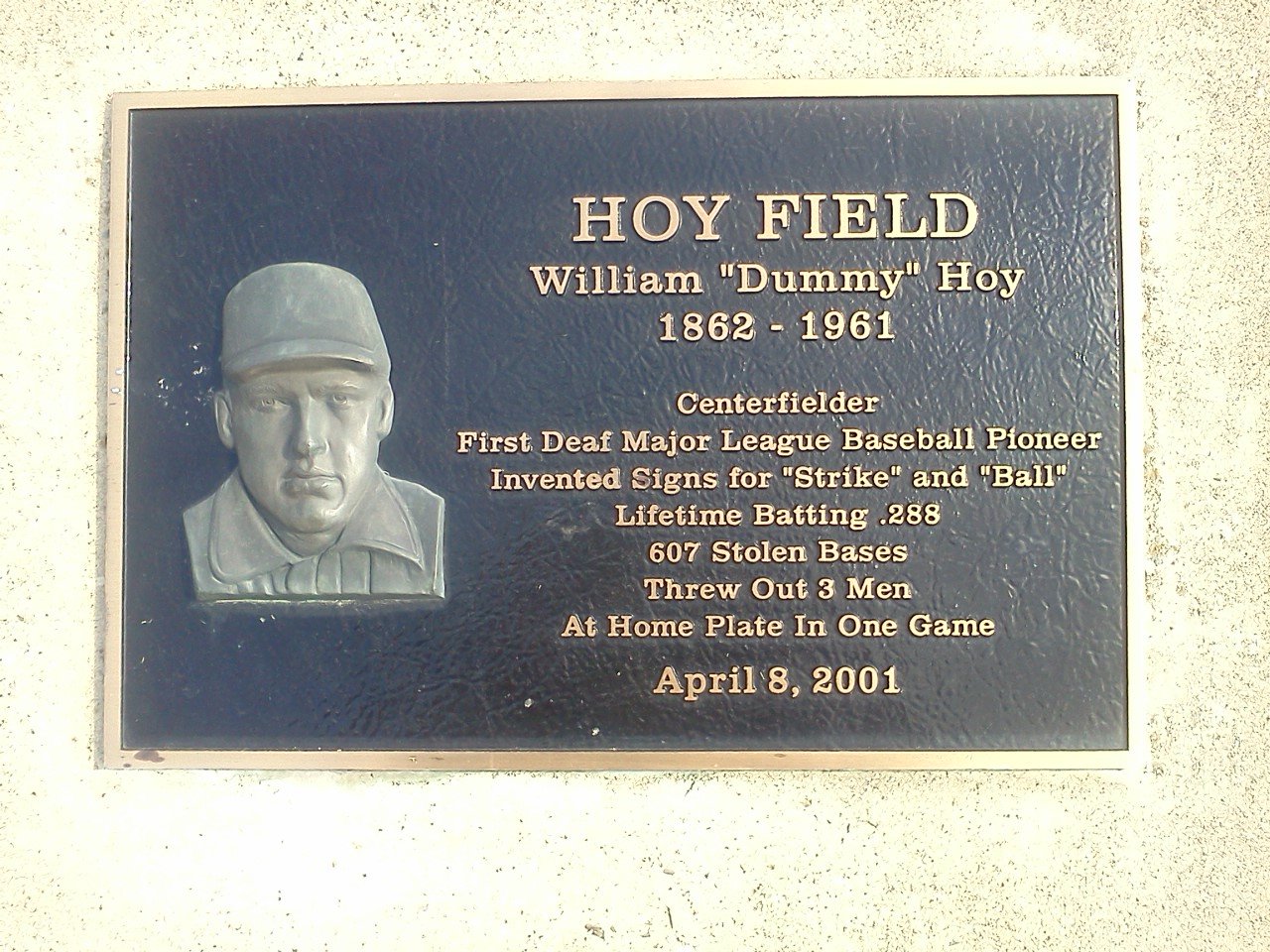

Hoy Field's Dedication Sign.

Hoy Signed Card.

In the 1880s, there were two other deaf-mute players, but baseball’s first deaf star was Dummy Hoy. From 1888-1902, Hoy played for eight different teams, finishing with a .288 batting average, 2044 hits, 1426 runs, 725 runs batted in, 607 stolen bases, and records for the most games played in center field and the most career putouts by an outfielder. Hoy is a member of the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame; the field at Gallaudet University (a congressionally-chartered university for the deaf and hard-of-hearing) is named for him. (2, 3)

Luther “Dummy” Taylor, the real-life pitcher who is the main character in the Havana Heat novel, was the second legitimate star who emerged from the deaf community. Taylor once faced Hoy in a game, the first time that two deaf players squared off against one another in a Major League baseball game. In 1904, Taylor won 21 games, and in 1906, he finished with a lower earned run average than his two Hall of Fame Giants teammates Christy Mathewson and Joe McGinnity. They won two pennants and a World Series title. Taylor played from 1901-1908, finishing his career with a record of 116-106, a 2.75 earned run average, and 767 strikeouts. (4)

Luther Taylor Pitching. Deaf Cultural Center.

There were other deaf players at that time also. But in the years since, there have been very few.

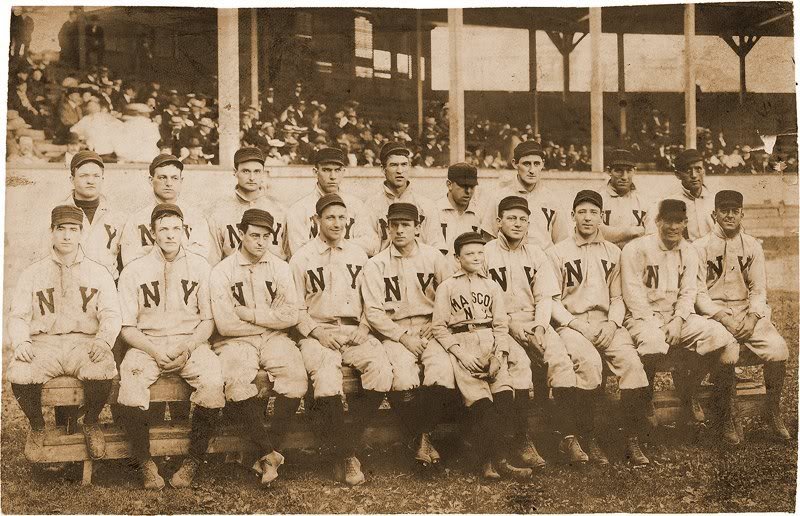

The New York Giants: Nice Guys Who Finished First

In 1901, the New York Giants’ pitching staff included three deaf players, Dummy Taylor, Dummy Deegan, and Dummy Leitner. There were other deaf players around the same time on other teams. Since then, the only deaf players I have been able to find were one in 1914, two in the 1940s, and one in 1993. (4)

In 1993, Curtis Pride became the first deaf player in more than 50 years to play a full season in the major leagues.

Even if there were a few more mixed in over the last century, it’s unlikely that baseball has had anything close to this level of representation by disabled players at any time in its history.

So why was the early 1900s such a high water mark for deaf players? They faced discrimination and disdainful nicknames, but the leagues, teams, and fans could be quite welcoming also. This certainly was the case with Taylor’s New York Giants, which employed a number of deaf players in that period. They also won championships during the same period with great team chemistry and a manager who brought out the best in his players.

1905 New York Giants. Taylor at top left.

As biographer Sean Lahman wrote, “The Giants didn’t just add Taylor to their roster; they embraced him as a member of their family. Player-manager George Davis learned sign language and encouraged his players to do the same. John McGraw did likewise when he took over as Giants manager.” (5)

Taylor’s teammate Fred Snodgrass later added that, “We could all read and speak the deaf-dumb sign language, because Dummy Taylor took it as an affront if you didn’t learn to converse with him. He wanted to be one of us, to be a full-fledged member of the team. If we went to the vaudeville show, he wanted to know what the joke was, and somebody had to tell him. So we all learned. And we practiced all the time.” (6)

Manager John McGraw liked to keep Taylor in the dugout during games that he wasn’t pitching. He was the team clown, he spooked other teams with the sounds he made, and he also could curse out the umpires in sign language without them knowing. But one of the umpires, Hank O’Day, had a deaf parent and understood sign language so he knew that Taylor was calling him blind as a bat. The umpire signed back to Taylor that he was ejected from the game: “You go to the clubhouse. Pay $25.” (7)

An umpire signalling that a runner is out.

Hand signals of various sorts have been important in baseball for many years. Catchers signal to pitchers about what kind of pitch to throw. Coaches signal signs to baserunners. And umpires throw hand signs for strikes, balls, and when a runner is safe or out. Some historians believe that umpires’ hand signals trace back to William “Dummy” Hoy, who reportedly asked umpires to make hand signals in his games. (8)

Other Reasons for the Early 1900s Peak in Deaf Players

Maybe so many deaf players succeeded in those days because Hoy and the early deaf players served as role models for others. And perhaps they proved to the teams of the day how good deaf players could be, prompting those teams to scout more players from schools like Kansas School for the Deaf, which was Luther Taylor’s alma mater and the school he returned to work at once his baseball career had finished. (1)

Also, within a few years, George Herman “Babe” Ruth became the game’s first legitimate slugger, belting long home runs that would change the game forever. Whenever the game changes, teams start looking for different kinds of talent, and Ruth’s rise signaled the end of an era when games were won with fundamental skills and fewer runs.

The live ball era began in earnest with Babe Ruth.

That’s not to say that deaf players could not have succeeded in the live ball era that Ruth ushered in. There simply were fewer people (handicapped or not) who had the athletic skills to succeed at such a high level, so perhaps even a community with some fundamentally good players had a harder time finding them roles in the major leagues. And later, when players of non-white races entered the game, there was a new influx of talent that made the leagues even more competitive. Still, one would have expected at least a few more top quality athletes would have emerged from the ranks of the deaf community; their almost complete absence on MLB rosters seems to indicate the disappearance of that career pathway to baseball that once existed for the Hoys and Taylors.

If I had to guess, I’d say that all of these reasons probably factored into the larger number of deaf players in the early 1900s. Particularly notable was the welcoming attitude of that team many of them played for, the New York Giants. And perhaps that team’s practices provide a model for how professional sports teams today could do a better job of encouraging and attracting the best athletes from non-traditional communities. Disparaging nicknames aside, when everyone is as open and accommodating to people from other backgrounds, it benefits society as a whole.

Sources:

(1) Brock, Darryl. Havana Heat (University of Nebraska Press, 2000).

(2) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dummy_Hoy

(3) https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/763405ef

(4) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dummy_Taylor

(5) Lahman, Sean. Dummy Taylor, in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Brassey's, 2004).

(6) Ritter, Lawrence. The Glory of Their Times (HarperCollins, 1966).

(7) https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/23/sports/baseball/world-series-2014-a-silent-link-between-the-giants-and-kansas-city.html

(8) Top image is cover art by Jez Tuya for the book The William Hoy Story by Nancy Churnin (Albert Whitman & Co., 2016). Other image sources referenced or public domain.