One of the most analyzed issues of the Greek art of the late classical and Hellenistic period is portrait art. The number of these works increased significantly in the 4th century BC. In the work of Lysippos, representation of Alexander dominates, for which portraying the sculptor had exclusivity (Papuci-Władyka 2001: 314). Lysippos created two separate types of performances of this kind: nude (attribute of heroes) and an official portrait on a horse, often placed in a military context.

The situation of Lysippos in the fourth century BC was unique. At the request of Philip II, he portrayed the young heir to the throne. Alexander, in his twenties, inherited the throne as a result of his father's death. The fact that he came from Heracles on the part of his father and Achilles on his mother's side, made him the hero of a new era, and the Eastern campaign grew in the eyes of contemporary writers to the act of recreating the deeds of Heracles himself (Stewart, 1991: 188).

Portrait sculpture so far has rarely appeared as a separate artistic task (Makowiecka, 1987: 117). Among the reasons for this state of affairs was the fact that the civic sense dampening hybris, pride was still strong - just like the trend of "ideal realism" (Makowiecka, 1987: 117), not exposing individual features of the model, and displaying the sum of its most beautiful features. The evolution of the full sculpture led to a break with the one-sided composition of the sculpture, which invited the viewer to get around it. The sum of the aspects of the character could only be understood by viewing it from various angles. The twist of the torso, the contrast of the direction of sight and gesture aroused the feeling of "controlled anxiety." (Boardman, 1964: 160).

The experience of showing emotions was used in individual portraits of rulers, bringing out their identity. Lysippos cultivated loyalty to nature and naturalism in his sculpture. In this way, many of his sculptures bear the features of a portrait, and this, along with joining the throne of Alexander, became extremely desirable. Makowiecka (1987: 119) risks the thesis that Alexander's portraits by Lysippos could, however, faithfully reflect his human nature. The ruler was to enter the skin of a hero and stand on the largest pantheon.

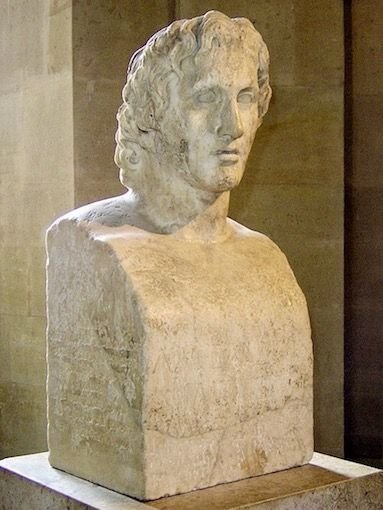

The amount of information about Alexander is very rich, and the source of the most comprehensive and accurate description of his appearance is Plutarch (Life of Alexander, around 100 AD, part 1: 4). The descriptions put him in the role of a conqueror - a hero whose face was compared to a lion, partly due to a mane of hair, which in a distinctive manner grew vertically in the middle part of the forehead. Numerous portraits of Alexander (it is impossible to identify the works of Lysippos and their copies) in their part heroized him. This applies to sculptures made after his death. The surviving examples of Alexander's iconography are limited to coins (after his death in 323 BC), mosaics in Pompeii, and herm from the villa of Hadrian in Tivoli.

With the founding of one of the first Alexandria, which was to mark the procession of Alexander to the East, numerous statues were created, from which many Hellenistic and Roman copies were drawn. Distinguishing their types:

- With the aegis (attribute of Zeus), holding the spear and palladium, testifying to Alexander’s rising preoccupation with divine attributes; naked, walking, with a tilted head, where the movement defines the mood and introduces a narrative.

- Portrait on a horse

Along with Alexander's return to Babylon, his performances take on further divine qualities, to finally match the gods, sometimes in an exaggerated way. Now the images have pretentious attitudes and very raised heads.

The portrait art of the next ancient centuries derives style and tone from Alexander’s performances by Lysippos. Dissemination of his style leads to the conclusion that he initiated a new approach to this genre. It allowed flexible idealization of the object of the sculpture (model) and balancing between idealism and realism. This is also the time to come in art.

References

Images: sources linked below

Photo: @highonthehog

- Papuci-Władyka, E., Sztuka starożytnej grecji, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN SA, Warszawa, 2001

- Stewart, A., Greek Sculpture: An Exploration, Volume I: Text, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1991

- Makowiecka, E., Sztuka grecka – krótki zarys, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Warszawa, 1987

- Boardman, J., Sztuka Grecka, Wydawnictwo VIA, Toruń, 1964

- Plutarch, The Parallel Lives, The Life of Alexander (Part 1: 4), the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1919

%202.jpg)