I want to write a series of posts going through the invention of Tesla’s Magnifying Transmitter. In this first introductory post I’ll briefly go through Tesla’s early years up until the discovery of the rotating magnetic field.

Enter the Dragon

The Chinese Zodiac is divided into 12 parts and an animal is assigned to each part. There is a snake, a horse, a sheep, a money, a rooster, a dog, a pig, a rat, an ox, a tiger and a rabbit, all animals that you could encounter someday somewhere. But there is one that is different in that you will never encounter it, the dragon.

The dragon lives in a different realm, a realm of fantasy and magic. And therefore a dragon can do things that ordinary folk can not. But it goes both ways, where ordinary folk succeed, a dragon fails, and where ordinary folk fail a dragon succeeds.

I have two idols and both did things that have not been repeated after they died. From the title of this paragraph you may have guessed the first; Bruce Lee. His style in martial arts, his precision, his power and most of all his speed make him stand out from all others.

But it is not Bruce (Xiao Lung; little dragon) that I want to write about, it is Nikola Tesla.

Both of them were born in the year of the dragon and both did the impossible, well..., things that are impossible to ordinary folk. It takes a dragon to know a dragon, and that is where I come in. I am born in the year of the dragon, in the month of the dragon and on the hour of the dragon. I am not a second Bruce or Nikola, I am Mage00000 and I want to show you around in the realm of the dragon.

Nikola Tesla

The story of Nikola Tesla started July 10th, 1856, at the stroke of midnight. His own autobiography starts with this intro, pay special attention to the italic passage:

The progressive development of man is vitally dependent on invention. It is the most important product of his creative brain. Its ultimate purpose is the complete mastery of mind over the material world, the harnessing of the forces of nature to human needs. This is the difficult task of the inventor who is often misunderstood and unrewarded. But he finds ample compensation in the pleasing exercises of his powers and in the knowledge of being one of that exceptionally privileged class without whom the race would have long ago perished in the bitter struggle against pitiless elements. (2)

This clearly refers to his Wardenclyffe project, his magnum opus. But we’ll cover that in great depth later on. Let’s first have a closer look at the young Tesla. First, to lighten the mood:

I had two old aunts with wrinkled faces, one of them having two teeth protruding like the tusks of an elephant which she buried in my cheek every time she kissed me. Nothing would scare me more than the prospect of being hugged by these as affectionate as unattractive relatives. It happened that while being carried in my mother's arms they asked me who was the prettier of the two. After examining their faces intently, I answered thoughtfully, pointing to one of them, "This here is not as ugly as the other." (2)

The main reason of Tesla's success is usually attributed to this:

In my boyhood I suffered from a peculiar affliction due to the appearance of images, often accompanied by strong flashes of light, which marred the sight of real objects and interfered with my thought and action. They were pictures of things and scenes which I had really seen, never of those I imagined. When a word was spoken to me the image of the object it designated would present itself vividly to my vision and sometimes I was quite unable to distinguish whether what I saw was tangible or not. (2)

But Tesla managed to gain control over this affliction and use it to his advantage. Thus he could design complicated machinery in his mind and see how they’d run without having to build one.

Tesla did a number of strange mental exercises either to increase his mental capabilities -a kind of mental fitness- or to try and understand the workings of the mind as in here.

I had noted that the appearance of images was always preceded by actual vision of scenes under peculiar and generally very exceptional conditions and I was impelled on each occasion to locate the original impulse. After a while this effort grew to be almost automatic and I gained great facility in connecting cause and effect. Soon I became aware, to my surprise, that every thought I conceived was suggested by an external impression. Not only this but all my actions were prompted in a similar way. In the course of time it became perfectly evident to me that I was merely an automaton endowed with power of movement, responding to the stimuli of the sense organs and thinking and acting accordingly. (2)

The importance of this conclusion will become clear when we arrive at the design of the Magnifying Transmitter.

During that period I contracted many strange likes, dislikes and habits, some of which I can trace to external impressions while others are unaccountable. I had a violent aversion against the earrings of women but other ornaments, as bracelets, pleased me more or less according to design. The sight of a pearl would almost give me a fit but I was fascinated with the glitter of crystals or objects with sharp edges and plane surfaces. I would not touch the hair of other people except, perhaps, at the point of a revolver. I would get a fever by looking at a peach and if a piece of camphor was anywhere in the house it caused me the keenest discomfort. Even now I am not insensible to some of these upsetting impulses. When I drop little squares of paper in a dish filled with liquid, I always sense a peculiar and awful taste in my mouth. I counted the steps in my walks and calculated the cubical contents of soup plates, coffee cups and pieces of food—otherwise my meal was unenjoyable. All repeated acts or operations I performed had to be divisible by three and if I mist I felt impelled to do it all over again, even if it took hours. (2)

It is said that Tesla had these many strange habits, but if you read carefully you will read that over time most of these wore off. This is confirmed by the only living person today who has personally met him (as far as I am aware of), his cousin William Terbo.

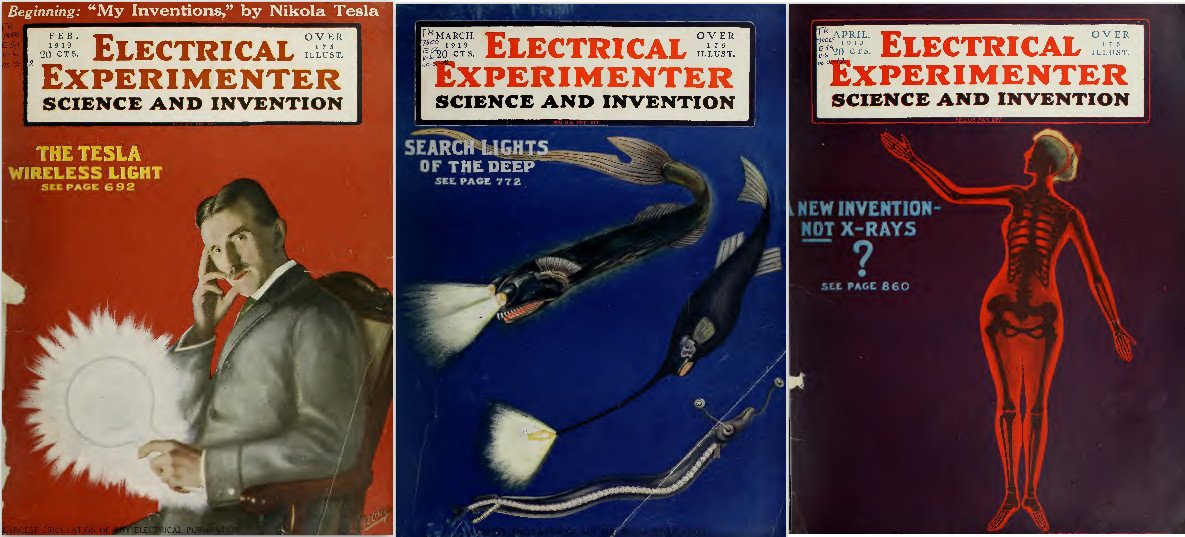

There are many more short anecdotes in Tesla’s auto biography but I do not want to copy them all here. You can read the entire biography here or download it as pdf or read it on Kevin Wilson’s site or download copies of the original publication here (issues 1006, 1106, 1206, 107 and 207).

There are many other sources but many of those are contaminated (later additions by Arthur Matthews and others, see this post).

In my eighteenth year I came to the cross roads. I had passed through the preliminary schools and had to make up my mind either to embrace the clergy or to run away. I had a profound respect for my parents, and so I resigned myself to take up studies for the clergy. Just then one thing occurred, and if it had not been for that, I would not have had my name connected with the occasion of this evening. A tremendous epidemic of cholera broke out, which decimated the population and, of course, I got immediately. Later it developed into dropsy, pulmonary trouble, and all sorts of diseases until finally my coffin was ordered. In one of the fainting spells when they thought I was dying, my father came to my bedside and cheered me: "You are going to get well." "Perhaps," I replied, "if you will let me study engineering." "Certainly I will," he assured me, "you will go to the best polytechnic school in Europe." I recovered to the amazement of everybody. My father kept his word, and after a year of roaming through the mountains and getting myself in good physical shape, I went to the Polytechnic School at Gratz, Styria, one of the oldest institutions. (1)

The first year at the polytechnic school was spent in this way - I got up at three o'clock in the morning and worked until eleven o'clock at night, for one whole year, with a single day's exception. Well, you know when a man with a reasonably healthy brain works that way he must accomplish something. Naturally, I did. I graduated nine times that year and some of the professors were not satisfied with giving me the highest distinction, because they said, that did not express their idea of what I did, and here is where I come to the rotating field. In addition to the regular graduating papers they gave me some certificates which I brought to my father believing that I had achieved a great triumph. He took the certificates and threw them into the waste basket, remarking contemptuously: "I know how these testimonials are obtained." That almost killed my ambition; but later, after my father had died, I was mortified to find a package of letters, from which I could see that there had been considerable correspondence going on between him and the professors who had written to the effect that unless he took me away from school I would kill myself with work. (1)

It was in the second year of my studies that we received a Gramme machine from Paris, having a horse-shoe form of laminated magnet, and a wound armature with a commutator. We connected it up and showed various effects of currents. During the time Prof. Poeschl was making demonstrations running the machine as a motor we had some trouble with the brushes. They sparked very badly, and I observed: "Why should not we operate without the brushes?" Prof. Poeschl declared that it could not be done, and in view of my success in the past year he did me ,the honour of delivering a lecture touching on the subject. He remarked: "Mr. Tesla may accomplish great things, but he certainly never will do this," and he reasoned that it would be equivalent to converting a steadily pulling force, like that of gravity, into a rotary effort, a sort of perpetual motion scheme, an impossible idea. But you know that instinct is something which transcends knowledge. We have, undoubtedly, certain finer fibers that enable us to perceive truths when logical deduction, or any other wilful effort of the brain, is futile. We cannot reach beyond certain limits in our reasoning, but with instinct we can go to very great lengths. I was convinced that I was right and that it was possible. It was not a perpetual motion idea, it could be done, and I started to work at once. (1)

While on my vacation, in 1882, sure enough, the idea came to me and I will never forget the moment. I was walking with a friend of mine in the city park of Budapest reciting passages from Faust. (1)

The sun was just setting and reminded me of the glorious passage:

"Sie ruckt und weicht, der Tag ist uberlebt,

Dort eilt sie hin und fordert neues Leben.

Oh, dass kein Flugel mich vom Boden hebt

Ihr nach und immer nach zu streben!

Ein schoner Traum indessen sie entweicht,

Ach, zu des Geistes Flugeln wird so leicht

Kein korperlicher Flugel sich gesellen!"

[The glow retreats, done is the day of toil;

It yonder hastes, new fields of life exploring;

Ah, that no wing can lift me from the soil

Upon its track to follow, follow soaring!

A glorious dream! though now the glories fade.

Alas! the wings that lift the mind no aid

Of wings to lift the body can bequeath me.]

As I uttered these inspiring words the idea came like a flash of lightning and in an instant the truth was revealed. I drew with a stick on the sand the diagrams shown six years later in my address before the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, and my companion understood them perfectly. The images I saw were wonderfully sharp and clear and had the solidity of metal and stone, so much so that I told him: "See my motor here; watch me reverse it." I cannot begin to describe my emotions. Pygmalion seeing his statue come to life could not have been more deeply moved. A thousand secrets of nature which I might have stumbled upon accidentally I would have given for that one which I had wrested from her against all odds and at the peril of my existence. (2)

Quotes from

1 1917-05-18: Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, Held at the Engineering Societies Building, Friday Evening

2 1919: My Inventions, published in the Electrical Experimenter

(to be continued)