September 17, 1949 is etched into my family’s minds for two reasons. It was the day my parents were married at Little Norway Anglican Church in Toronto. My aunt had to stand in as the maid-of-honour that day as my mother’s best friend, Eileen, who was supposed to take that part, was caught up in the aftermath of the second reason.

The burning of the steamship SS Noronic in the Toronto Harbour, which took upwards of 139 lives. One Canadian and the rest Americans perished in the fire that started in the early hours of that day.

Great Lakes Steamship Cruising

Sometimes referred to as “inland seas”, the great lakes of North America form the largest inland body of fresh water in the world. The group of five interconnected lakes straddle the Canadian-American border with the exception of Lake Michigan which is completely in the US. With a mass of 90,000 square miles and stretching 1,555 miles they provided a varied playground for those with means and desire to take leisurely cruises.

Cruise ships plied the waters of the lakes from the early 19th century onward. It was the opening of the fourth Welland canal in 1913 between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario which expanded the market for luxury steamships travelling the great lakes.

The era between 1913 and 1965 saw luxury steamships that rivalled the great ocean liners taking passengers around the great lakes on cruises. It was a popular activity and profitable for the ship lines running them. A lack of meaningful safety regulations helped keep their costs down.

SS Noronic

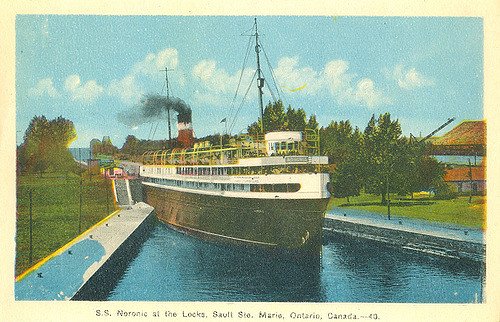

The Northern Navigation Company had the Noronic built by the Western Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Company of Port Arthur, Ontario in 1913. At the time she was one of the largest steamships on the great lakes at the time measuring 362 feet x 52 feet x 24.8 feet (110 metres x 15.8 metres x 7.5 metres)and a tonnage of 6,905 with five decks. She could carry up to 600 passengers.

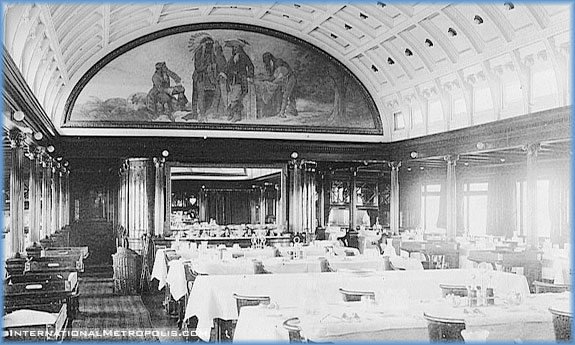

The Noronic would be referred to as “The Queen of the Lakes”. She was outfitted in luxury and included: a ballroom, dining hall, barber shop, beauty salon, music & writing rooms, library, children’s playroom and even had its own newspaper printed on board for the passengers. The passage ways were lined with wood that had been oiled with lemon oil frequently over the 40 years the shipped sailed the great lakes.

Her maiden voyage was delayed when one of the biggest storms in Great Lakes history roared into the area. For three days, the SS Noronic sat in the harbour while the storm raged with hurricane force winds and waves upwards of 49 feet high (about 15 meters). Over 250 died, 12 ships were sunk and 29 other ships would be damaged and stranded.

Canada Steamship Lines

Not long after her maiden voyage the Noronic and all the rest of the ships of the Northern Navigation Company were acquired by Canada Steamship Lines. CSL remains today as one of Canada’s largest shipping lines. In 1981 Paul Martin was one of a small group buying CSL from Power Corporation. He would later become the Right Honourable Paul Martin, Prime Minister of Canada from 2003 to 2006.

The Noronic’s Master — Captain William Taylor

Born in Moore Township, Ontario on September 1, 1883, Captain Taylor began his sailing career at the age of 18 when he was taken on as a wheelman on an American ship. He worked his way up through the ranks and acquired his Master’s papers in 1932.

By 1934 he was serving as the Master of the SS Huronic, one of two sister ships to the Noronic. He served briefly as the Master of the other sister ship, the SS Harmonic. He wasn’t master when it burned in the CSL sheds in 1945 with no loss of life.

The Noronic’s Final Voyage

The SS Noronic set out for what was to be the last trip of the season on September 14, 1949 from Detroit. Stopping in Cleveland for more passengers it would be carrying 529 passengers, all American. The crew consisted of 171 Canadians.

The week long trip was to travel to Prescott, Ontario and the Thousands Islands in the St. Lawrence River before returning via Toronto to Detroit. The Noronic would have then sailed to Sarnia where it would remain for the winter.

Pier 9 In Toronto Harbour

It had been an uneventful trip when the SS Noronic steamed into Toronto Harbour and tied up at Pier 9. Today, so many changes have been made at the Harbour and so much of the harbour claimed for land, where the bow of the Noronic was tied up is now the lobby of the Westin Harbour Castle Hotel.

The captain and all but 15 of the crew went ashore along with most of the passengers. They headed into downtown Toronto to enjoy the evening. Many of the remaining passengers went to the dancehall. Since the bar was closed while in port, they took their own bottles and partied together.

When Captain Taylor returned to the ship around 1:30am most of the passengers and crew had returned and the ship was quiet.

Fire Is Discovered

Around 2:30am a passenger notice smoke on C deck and traced it to a linen closet near a ladies washroom. He located a bellboy who rather than sound the alarm ran to get the keys to the closet from the steward’s office on D deck. When he opened the closet, the inrush of air fueled the smoldering fire and it flared up and out into the corridor.

The passenger and the bellboy tried to fight the flames but the fire extinguisher was useless and the fire hose didn’t work properly. They fled sounding the alarm. The fire moved quickly fueled by the well oiled wood lining the corridors and the open stairwells provided a chimney effect to feed the fire oxygen.

Captain Taylor was notified and the first mate sounded the ship’s whistle. But instead of the distress signal the whistle jammed itself into one long unrelenting shriek. Some described it as the ship’s death cry.

Panic and Fear Takes Over

Within 10 minutes half the ship was on fire and within minutes more, the rest of it was. Panic ensued. The passengers had never been given any kind of emergency drill and there was only one exit passageway instead of an exit on each deck.

Most members of the crew escaped the ship immediately. Those who remained, including Captain Taylor raced through the parts of the ship they could reach hammering on doors to rouse sleeping passengers. In some cases they smashed out windows to help passengers get off the ship.

Panic led to desperation fuelled by the rush of the flames. Passengers started jumping off the ship, many into the cold water of the harbour, some onto the pier risking injuries or death. One person did die on the pier. Others missed and landed on other decks, injuring themselves.

When fire and rescue arrived from land, they attempted to swing rescue ladders around to the ship only to have panicked passengers leaping onto them and either breaking them or, in one case, toppling the truck. Captain Taylor had to jump over the bow to avoid the flames.

Those arriving on shore were quick to start rescuing people from the cold water of the harbour. There was only one death from drowning. At first they tried to lower ladders for people to climb out of the water but they were so panicked they overloaded the ladders and they sank into the harbour. Ropes were used.

Ambulances, taxis and any other vehicle willing to help was pressed into service to take the injured to nearby hospitals. Many of the injured suffered from burns. The lone Canadian casualty, Louisa Dustin, an employee of Canadian Steamship Lines and travelling as a passenger, died a few weeks later as the result of her burns.

Fire boats finally arrived to fight the fire from the water while ladder trucks on the dockside rained water onto the fierce fire.

Hours Later the Fire is Out

Dawn was starting to light the sky when the last of the fire was extinguished around 5:3am. At times the flames and heat had been so intense during the night that parts of the ship had been warped.

The name of the ship on the bow was down at the waterline by the time the fire was out. Divers would have to search later below the waterline to find some of the dead. It would be hours later, around 10am before the fire ravaged shell had cooled enough for anyone to venture onboard. What lay before them was almost beyond description.

Edwin Feeney was a reporter for the Toronto Star at the time and one of the first reporters allowed on. Years later, after he had retired, I knew him. At the mention of the Noronic, you could see his face cloud over and his involuntary shutter. He didn’t want to talk about those memories.

Most on board burned to death. Some died trampled underfoot by fleeing passengers. Groups of passengers were found clustered together in rooms, presumably family members. The bodies were found all over the ship. Some bodies were never found, thus the uncertainty of how many actually died. About 118 were known killed and figures range up to 139 but that is not confirmed.

Dealing With The Aftermath

The Horticultural Building at the CNE (Canadian National Exhibition) grounds was pressed into service as a temporary morgue to deal with the remains. Family members would be weeks trying to identify clothing and personal possessions of their loved ones. It would be a year before the unclaimed remains were laid to rest at Mount Pleasant Cemetary in Toronto.

St. Michael’s Hospital in downtown Toronto dealt with up to 100 injured passengers and their care for weeks afterward.

The Horticultural Building at the CNE (Canadian National Exhibition) grounds was pressed into service as a temporary morgue to deal with the remains. Family members would be weeks trying to identify clothing and personal possessions of their loved ones. It would be a year before the unclaimed remains were laid to rest at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Toronto.

The landmark Royal York Hotel became a reception centre and shelter for the rest of the passengers. My mother’s friend Eileen was an employee there. She had to return to work that day to help with the passengers.

The Federal Inquiry

The federal government held an inquiry into the disaster. They deemed the cause of the fire to be likely a cigarette dropped in the linen closet.

In 1950 the CSL ship Quebec burned after a fire was deliberately lit in a linen closet. The similarities raised the possibility that the Noronic had been arson as well but was never pursue or proven.

The inquiry found Captain Taylor and Canada Steamship Lines at fault for the disaster. They ruled that Captain Taylor should have had enough awareness of safety needs to have seen the possibility of a tragedy happening. They suspended his master’s certification for one year.

Canada Steamship Lines settled the various claims that passengers and families made against them for $2million dollars.

What Happened to Captain Taylor?

Canada Steamship Lines continued to pay Captain Taylor through the shipping season of 1950 and would have taken him back after his suspension. He never asked for his certification back. Nor did he ever sail.

He returned to Sarnia. He and his wife took up residence in a small apartment in Sarnia and he took a job as a desk clerk at a local hotel. He died in February 1962 at the age of 79 and his wife passed in 1970.

The End of the Steamship Era

The strict safety regulations brought in after the Noronic fire signalled the end of the era for Great Lake steamships. The cost of retrofitting them to meet the new regulations was just too prohibitive. Some held on until the last one was retired in 1967.