Hatshepsut was one of the most intriguing rulers of ancient Egypt. In spite of being a legitimate daughter of Tuthmose I, second pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty, and Queen Ahmose, she did not succeed his father to the throne. Instead, she was forced to marry her half-brother, a son of Tuthmose I and a concubine, who inherited the crown as Tuthmose II.

If Hatshepsut had been born a man, the regal power would have been handed to her on a golden plate, but because she was a woman—women in Egypt were excluded from the succession to the throne at the time—she had to step back and let her husband rule the land.

Hatshepsut Declares Herself Pharaoh of Egypt

Hatshepsut and Tuthmose II failed to produce a male heir. After the pharaoh's early death, his eight-year-old son, again by a concubine, ascended the throne as Tuthmose III. Hatshepsut then takes the position as the young king's queen regent—but not for long. Soon, she pushed Tuthmose III aside and proclaimed herself ruler of Egypt. Thus she became the first female pharaoh of ancient Egypt.

What induced Hatshepsut to abandon the role of queen regent? We don't know for sure. The most plausible reasons for her break with the traditional role of queen regent may have been Hatshepsut's thirst for power and her genuine belief in the divinity of the pharaoh. After all, she was a true blue blood while her half-nephew's mother was a commoner. Scholars believe that Hatshepsut's seizure of power was aided by important administrative officials at court, who were engaged in a power struggle against the military.

The Egyptian army had achieved great influence under Hatshepsut's father, through their victory over the Hyksos—the enemy occupying northern Egypt. Tuthmose I, a great warrior, had also led successful military campaigns against Nubia and Syria, expanding the borders of Egypt along the way. It is believed that the military wanted to fight on, favoring a policy of conquest; the officials wanted Egypt to stay within the traditional borders. Hatshepsut sided with the officials, demanding peace.

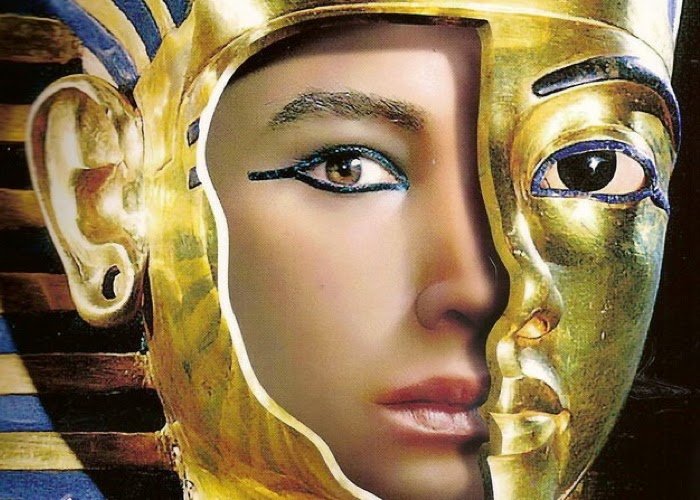

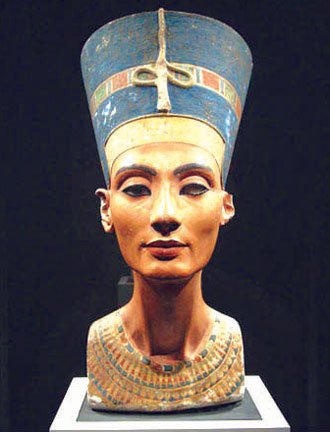

Hatshepsut's Appearance

Ancient Egyptians believed that the pharaoh's role could not be adequately carried out by a woman. Aware of this religious belief, Hatshepsut decided to portray herself as a male. However, this ''look'' was more characteristic of her later rule. Statues dating from the early years of her rule as a pharaoh show us Hatshepsut with the body of a woman but with the striped Nemes headdress and uraeus cobra, which were the symbols of a king.

Hatshepsut's Rule

Hatshepsut's reign was long and prosperous; she ruled Egypt for 21 years and 9 months. During this time, Egypt was blessed with peace. She re-open and expanded Egypt's trade networks that had been interrupted during the Hyksos occupation of Egypt and commissioned a trade expedition to the mysterious Land of Punt. This was a land on the African shore of the Red Sea, perhaps in present-day Eritrea. The land produced and exported gold, ebony, ivory, wild animals, slaves, African Blackwood, and myrrh. Ancient Egyptians used myrrh, along with natron, for the embalming of mummies.

Little is known about Hatshepsut's military activity.

Hatshepsut the Builder

Hatshepsut was one of the greatest builders in ancient Egypt. She managed to raised and renovated the temples and shrines from Nubia to the Sinai. She erected 4 obelisks at the temple of the god Amun at Karnak and she also ordered hundreds of statues of herself. She set against high cliffs at Deir el-Bahari on the west bank of the Nile. Near the Valley of the Kings is her mortuary temple complex called the Djeser-Djeseru or the Holy of Holies. It is one of the most beautiful and impressive temples of the ancient world. The master builder of this limestone masterpiece was probably Hatshepsut's royal architect and lover Senenmut. Senenmut left many hidden traces of himself in the queen's temples: portraits, statues, and inscriptions with his name. As a special sign of the queen's love, he was given permission to have a secret tomb built under the queen's mortuary temple.

Sadly, in 1997, the Temple of Hatshepsut became the site of a vicious terrorist attack known internationally as the Luxor Massacre. Behind the attack was the Egyptian Islamist organization Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyah, attempting to overthrow the secular, elected government of President Hosni Mubarak. Sixty-two people—mostly foreign tourists—brutally lost their lives in the attack. The incident seriously affected the Egyptian economy and tourist industry at the time but it also led to increased security at tourist sites.

Hatshepsut's Death

It is not known how and why Hatshepsut died. After her death, around 1458 BC, Hatshepsut's half-nephew, Tuthmose III finally seized power of the land. A great warrior like his grandfather, he is written down in history as the Napoleon of ancient Egypt. His military victories made Egypt one of the richest and strongest lands on Earth.

In the latter part of his life—approximately twenty years after Hatshepsut's death—Tuthmose III decided to erase his stepmother from history. He obliterated the name of Hatshepsut from stelae and temple walls, defaced her features, and destroyed or renamed her statues. Ancient Egyptians believed that the spirit of a deceased could survive death only if some remembrance of the deceased— a mummified body, a statue or name carved in stone or wood—remained in the land of the living. Hatshepsut's rule was to be forgotten.

The Possible Discovery of Hatshepsut's Mummy

In 2005, Egyptologist Zahi Hawass focused his attention on a mummy called KV60a, which had been discovered by Howard Carter, the person that also discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun a century earlier in the Valley of the Kings. In the tomb KV60, Carter found two denuded mummies of women. One mummy was lying in a coffin, the other on the floor. The mummy in the coffin was later brought to the Egyptian museum while the mummy lying on the floor was left behind. In 1998, Egyptologist Donald Ryan entered the tomb KV60 and studied the naked mummy, suspecting it to be Hatshepsut. Her left arm was crooked across her chest in a burial pose common to the 18th-Dynasty Egyptian queens.

Two decades later, Hawass rounded up all the unidentified and possibly royal female mummies from the 18th Dynasty, including the two that had been found in KV60. In 2006 and 2007, the mummies passed through a CT scanner to be studied. The CT results were inconclusive. .

Then Hawass's team of scientists had another idea. They scanned the wooden box that has engravings of Hatshepsut's name, it was believed to contain Hatshepsut's liver. The box was scanned and the result was astonishing: the scanner detected a tooth. The tooth was identified as a secondary molar with part of its root missing. The jaw images of the assembled mummies were re-examined, and there in the right upper jaw of the KV60a was a root with no tooth. The root of the mummy and the tooth matched. While some scientists still remain skeptical about the findings of the research, Hawass is confident about his discovery.

The circumstances of Hatshepsut's death is no longer a mystery. Hatshepsut probably died of an infection caused by a blistered tooth, with complications from advanced bone cancer and diabetes. The high priests of Amun may have moved her body from the burial chamber to the tomb of her nurse to protect it from grave robbers, and there it was destined to spend the next three thousand years before finally resurfacing at the dawn of the 21st century.

References

Egypt: People-Gods-Pharaohs

Hatshepsut: The King Herself

Hatshepsut

Images: 1 2 3 4 5