Donald Hoffman argues that all of spacetime is an abstraction for a deeper and unobserved reality. According to this line of reasoning, spacetime only exists when it's being perceived. What do you think?

The Reality Illusion

Introduction

Whatever reality is, it's not what you see. What you see is just an adaptive fiction. -Donald Hoffman

In browsing through the available eBooks from my local library, I came across The Case Against Reality by UC Irvine Professor Emeritus, Donald Hoffman, and I read it over the weekend. The book presents a fascinating discussion on the nature of reality, a topic that has intrigued me for years.

In this book, Hoffman uses three major frameworks to argue that consciousness - not spacetime - is at the root of reality, and that our perceived reality is very different from the objective reality that actually exists.

The crux of Hoffman's argument relies on something of his own creation, called the Fitness Beats Truth Theorem (FBT), which he conjectured and claims that Chetan Prakash proved. According to this theorem, if perception agents that optimize for evolutionary fitness compete in evolution against perception agents that optimize for truth, natural selection favors the fitness-optimizers and the truth-optimizers go extinct.

In addition to the Fitness Beats Truth theorem, Hoffman also introduces us to the Interface Theory of Perception (ITP). According to this theory, the "reality" that we observe is something akin to an operating system interface. In this view, the things we see are nothing more than avatars and icons that provide useful shortcuts in order to allow us to survive for long enough to reproduce. A file icon on a computer desktop doesn't say anything about the underlying bits on the hard disk. Similarly, ITP argues that when we see an apple or a train or a snake, we're not seeing the reality of those objects, just abstractions that evolution has given us in order to guide our decisions. Provocatively, Hoffman argues that these representations don't even exist at all when nobody is perceiving them.

Finally, Hoffman closes the book with a concept that he calls, conscious realism. According to mainstream science in many fields, our perceptions are approximations of what actually exists. We don't perceive things perfectly, but the things that we perceive exist independently of our perception, and our perception is tuned to perceive the most useful things the most accurately. With conscious realism, Hoffman argues that no, the things we perceive don't exist. They are abstractions that we use to simplify our decision making. Over and over, Hoffman says that we should take our perceptions "seriously, but not literally". Stepping in front of a speeding train will end our evolutionary game, but the resultant collision doesn't reflect the true nature of the end of the game. In particular, conscious realism argues that the core reality is driven by the interplay of conscious agents (whose nature we cannot yet imagine) and spacetime is a tool that these agents have created to simplify their decision making.

For a sense of this argument in 22 minutes, you can see Hoffman's 2016 TED talk:

In the remainder of this post, I'll take a look at FBT, ITP, and conscious realism in a bit more detail.

Fitness Beats Truth (FBT)

In this context, "fitness" refers to evolutionary fitness, which describes the probability of successful reproduction, and "truth" refers to an accurate representation of the observed reality. According to FBT, "fitness" beats "truth" at evolution.

In addition to the previously mentioned proof of FBT by Chethan Prakash, Hoffman and his students have also been running simulations in Evolutionary Game Theory, and observed matching results. As a result, Hoffman has reached the conclusion that natural selection favors perceptions that chase after "fitness" instead of perceptions that chase after "truth". The FBT theorem describes it, thusly:

Over all possible fitness functions and a priori measures, the probability that the Fitness-only perceptual strategy strictly dominates the Truth strategy is at least (|X| − 3)/(|X| − 1), where |X| is the size of the perceptual space. As this size increases, this probability becomes arbitrarily close to 1: in the limit, Fitness-only will generically strictly dominate Truth, so driving the latter to extinction, Fitness Beats Truth in the Evolution of Perception.

Obviously, a book in the popular media is not going to have all the technical details to describe how Hoffman reached his conclusions, so I can't say whether the proofs and conclusions are valid or not, but here's how I understand it.

If we have a conscious agent that optimizes for reality (truth), it can guide our decisions, but it is likely to be computationally difficult and slow. In the evolutionary game, slow decisions can lead to death. However, if we have another agent that optimizes for fitness by presenting with abstractions that guide our decision-making quickly, we are more likely to survive and reproduce, even if those representations have very little in common with actual reality.

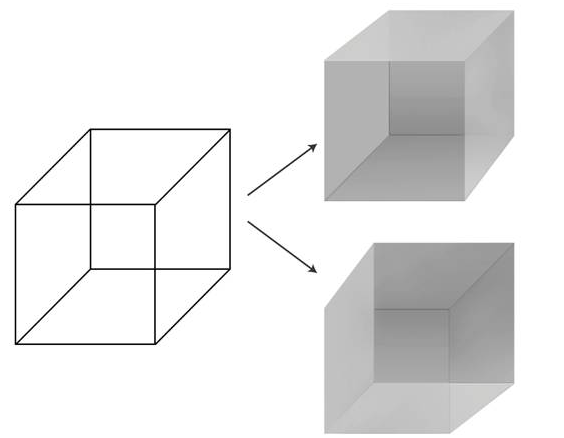

A great deal of the book is dedicated to using optical illusions - such as the Necker Cube to persuade the reader that we construct our reality rather than observing it. In these examples, two viewers may perceive them differently, and even the same viewer may perceive them differently at different times.

The Necker Cube, wikimediea, CC3

He also drew on examples from nature where animals are tricked by perception "shortcuts" into dysfunctional behaviors. One such example was the Australian Jewel Beetle, which nearly went extinct because the males of the species preferred discarded beer bottles to female Jewel Beetles. Another was a moose trying to mate with a statue.

According to Hoffman, these biological shortcuts of perception show that the perception algorithms prefer speed to accuracy, and it supports the notion that the way we perceive a thing is optimized for fitness and not truth.

Interface Theory of Perception (ITP)

According to the Interface Theory of Perception (ITP), all of spacetime is an abstraction that our species has developed in order to help us make better evolutionary decisions. When we look at a red apple across the room, that apple is giving us some information about factors that are important to us in the underlying reality, but that apple's existence is more like a windows file icon than it is like a tangible object. Like the windows file icon protects us from the need to worry about the locations of bits on disk and in memory, the red apple data structure protects us from the need to wade through complex factors in the underlying reality. When we don't need it any more, we stop perceiving it, and the red apple ceases to exist (until we need to perceive it again).

Hoffman acknowledges that this runs counter to our strongly experienced intuitions, but he points out other times in history when we have had to reorient our scientific understandings in ways that ran counter to our perceptions. Obvious examples being the shift from a flat earth to a round one and shifting from an Earth-centered universe to one where Earth has no special standing. Additionally, Hoffman cites physicists who claim that the widely sought "theory of everything" will have to abandon the concept of spacetime. For example, he cites Nima Arkani-Hamed from the prestigious, Institute for Advanced Study, who said:

"Almost all of us believe that space-time doesn't really exist, space-time is doomed and has to be replaced by some more primitive building blocks."

And even, Galileo, who said:

“I think that tastes, odors, colors, and so on . . . reside in consciousness. Hence if the living creature were removed, all these qualities would be wiped away and annihilated.”

Additionally, the book draws on the concepts of the Holographic Principle and the Holographic Universe to argue that current physics already makes room for the possibility that spacetime is an abstraction.

Conscious Realism

In the last chapter of the book, Hoffman speculates about what the fundamental reality might be like if spacetime is just a decision making tool for some conscious agents that hide behind our avatars at a deeper layer of reality. He points out that when we look in a mirror, we see our body doubles, but we don't see the things that really make us who we are: we don't see the joys, pain, memories, hopes, aspirations and experiences that drive so much of our decision process.

Throughout the book, Hoffman has argued that - despite centuries of research - there's no theory to describe how consciousness arises from unconscious matter, and he argues here that the opposite is true. In fact, he claims that conscious agents are operating at a more fundamental layer of reality, and they are the ones cooking up all of our perceptions of space and time.

Earlier in the book, he introduced a diagram to describe the stateful process for conscious agents that alter the state of the world (reality) by a decision making process. In this diagram, our experiences are influenced by our perception of the world and they drive our decision-making. In turn, the actions we take are driven by those decisions, and - closing the loop - when we act, we change the state of the world. i.e.

[World] -> Perceive -> [Experiences] -> Decide -> [Actions] -> act -> [World]

In the final chapter on conscious realism, Hoffman introduces a modified diagram where the "World" is replaced by a collection of two conscious agents. In this model, each agent experiences the results of the other agent's actions, makes a decision, and acts accordingly. The loop is closed when the second agent's actions feed into the first's experiences.

Agent 1: Perceive -> [Experiences] -> Decide -> [Actions] -> act -> Agent 2

and

Agent 2: Perceive -> [Experiences] -> Decide -> [Actions] -> act -> Agent 1

Hoffman argues that the number of conscious agents can be increased to infinity, and that's what he imagines we'll find if we're ever able to investigate reality beyond the confines of our spacetime interface.

Conclusion

In this book, Hoffman definitely weaved FBT, ITP, and conscious realism into a fascinating story line that leads to a possible path forward against Chalmers' Hard Problem of Consciousness. Unfortunately, postulating consciousness as somehow lurking behind a fictional reality of our perception still leaves open the question of where the consciousness comes from, and what it's made of. It's fun to think about, but I'm not sure how useful it is at this point. Still, a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step, right? Is this a step in the right direction?

As @cmp2020 mentioned when we were discussing this concept in the car, this argument goes back to Descarte's "Cogito, ergo sum" (I think, therefore I am). And with the example of Plato's Allegory of the Cave, Hoffman even points out that it has philosophical roots going back as far as the ancient Greeks. But the difference now is that the lens of "Evolutionary Game Theory" creates a mechanism by which we might be able to inspect these hypothesized deeper layers of reality.

If you would like to hear more from the author, you might enjoy listening to this 40 minute interview from the Institute of Art and Ideas or this three hour interview with Lex Friedman. A shorter version (~17 minutes), with clips from Friedman's interview is available, here:

When reading this article, I was reminded of a blog article that I posted in 2006 (which is now gone). In that article, I had written:

Could nature be a model, an abstraction, that enables consciousness to achieve some purpose? I was thinking Sunday, my life is saturated with examples of seeming reality which is actually created by consciousness... "If a tree falls in the woods, does it make a sound"? I learned in jr. high that it does not. Colors. I look at the grass and it has a property of 'green-ness'. But does it?

No. The grass has no color. It appears green, to me, because light from the sun, of a certain speed, hits the grass and reflects into my eyes and gets processed by my brain. Only then does green 'appear'. My consciousness gives the grass it's color. If no one (capable of perceiving color) is viewing the grass, the light is not being processed and the grass does not appear to be green.

So, even though Hoffman's ideas are jarring, I don't think they're totally implausible. The book was definitely thought provoking. In the end, though, I have a hard time with the idea of these abstractions popping in and out of existence when we need them. If I leave my car windows open and a rainstorm happens, I don't need to observe the car (or the rain) for the car's interior to get drenched. The ideas are interesting, and engaging, but it's hard to persuade oneself that every perception from birth to death is a work of evolutionary fiction. Also, I think it's reasonable to wonder why evolution and natural selection are necessary components of Hoffman's conjectured underlying world?

In Hoffman's model, reality is something like the Matrix or like a game of Minecraft. What's different about these two concepts? The Matrix is a work of fiction. In that universe, the players don't know that they're in a pretend world. In Minecraft, which actually exists, the players operate outside the world, and they know the difference between fiction and our perceived reality. I'm not aware of any sort of artificial world where conscious players are so immersed in the game that they don't know the difference between fiction and our perceived reality. Hoffman is asking us to believe that our perception is more like The Matrix at an upper layer than like Minecraft at a lower layer. To me, that difference feels like a pretty big leap.

What do you think? Is reality an illusion?

Thank you for your time and attention.

As a general rule, I up-vote comments that demonstrate "proof of reading".

Steve Palmer is an IT professional with three decades of professional experience in data communications and information systems. He holds a bachelor's degree in mathematics, a master's degree in computer science, and a master's degree in information systems and technology management. He has been awarded 3 US patents.

Pixabay license, source

Reminder

Visit the /promoted page and #burnsteem25 to support the inflation-fighters who are helping to enable decentralized regulation of Steem token supply growth.