In the previous exercise, we worked with the primary colors, we learned how to lighten and darken them. This time, we are going to practice with the secondary colors.

First, we must make a small clarification. Color theory tells us that primary colors are those colors that cannot be obtained by mixing other colors, and it speaks of magenta, cyan and yellow. But, over the centuries, artists did not dedicate themselves to thinking about color in a theoretical and conceptual way, but it was with practice, based on their craft, as they were observing the behavior of different colors. So, traditionally, painters have used various shades of reds, yellows and blues as primary colors. And hence, in different painting manuals and internet sites, we find triads of primaries that differ from each other: carmine, magenta, cyan, prussian blue.... Of course, whichever three are chosen, they remain equidistant on the color wheel. If you remember, I recommended in the previous post to use cerulean blue, medium cadmium yellow and carmine or alizarin red. Finally, it turns out that, in addition, the colors marketed by manufacturers are not exactly pure in that theoretical sense either.

Secondary colors

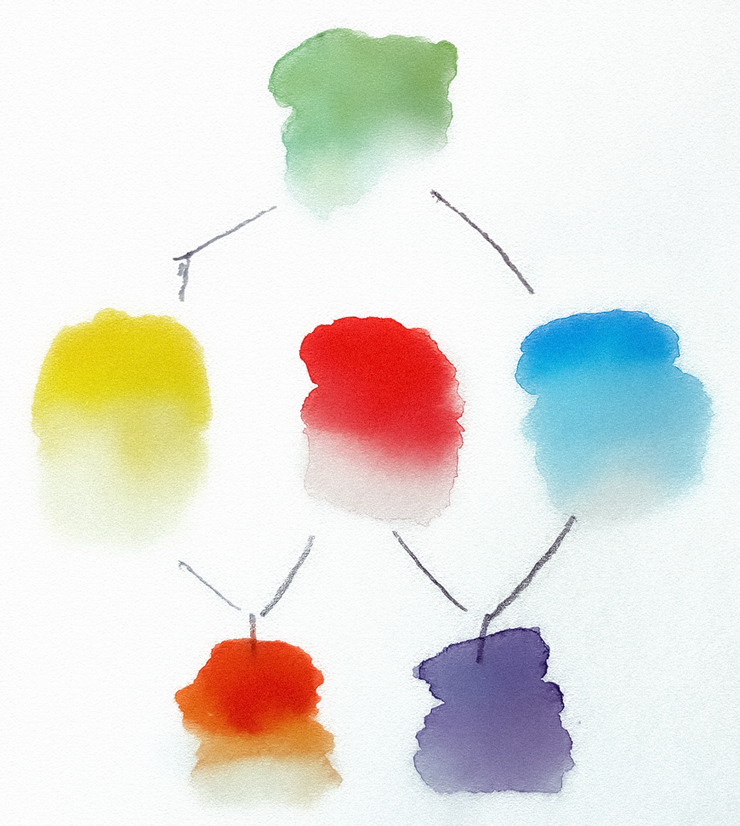

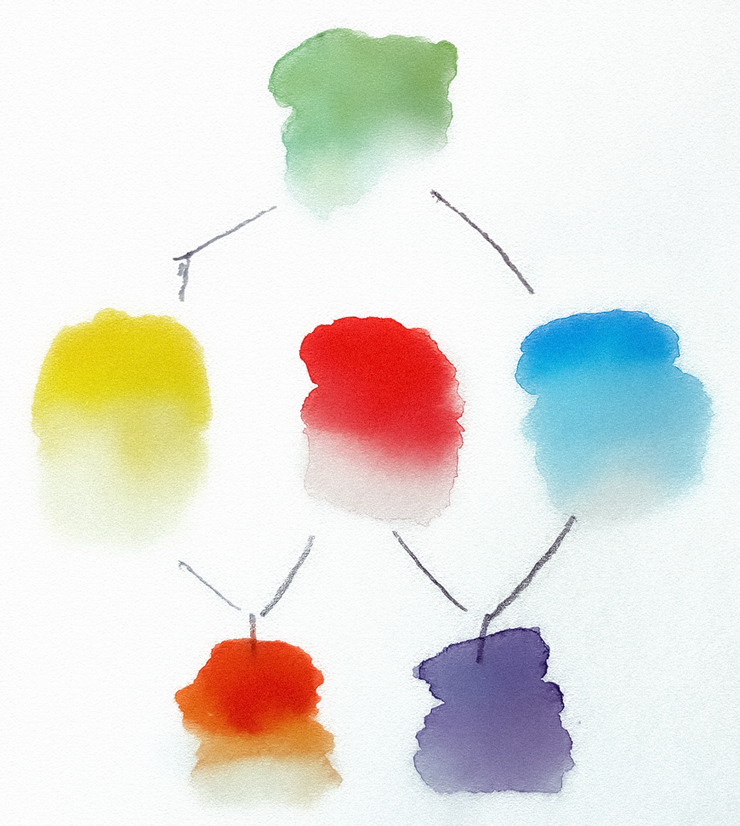

But let's get down to secondary colors. Secondary colors are those colors that are obtained when two primaries are mixed in equal quantities. Thus we have that blue and yellow give us green; the mixture of yellow and red, orange; and from blue and red we obtain violet. The purity or luminosity of the color obtained will depend on the shade of the blue, red or yellow used as primary. In fact, a great variety of secondary colors can be produced depending on how we mix the primaries, which would fall into one of the categories of green, orange and violet. To know exactly what the secondary colors are, we must consider that they must be the exact complementary colors of the primary colors.

Complementary colors

Each of the three secondary colors is considered, in turn, a complementary color of one of the primary colors, precisely the one that has not been used for its composition. Thus, green is complementary to red, orange to blue and violet to yellow. Complementary colors are found in opposite places within the chromatic circle and are the least similar to each other. Therefore, they are colors that contrast a lot, or that can be used to obtain chromatic grays, for example.

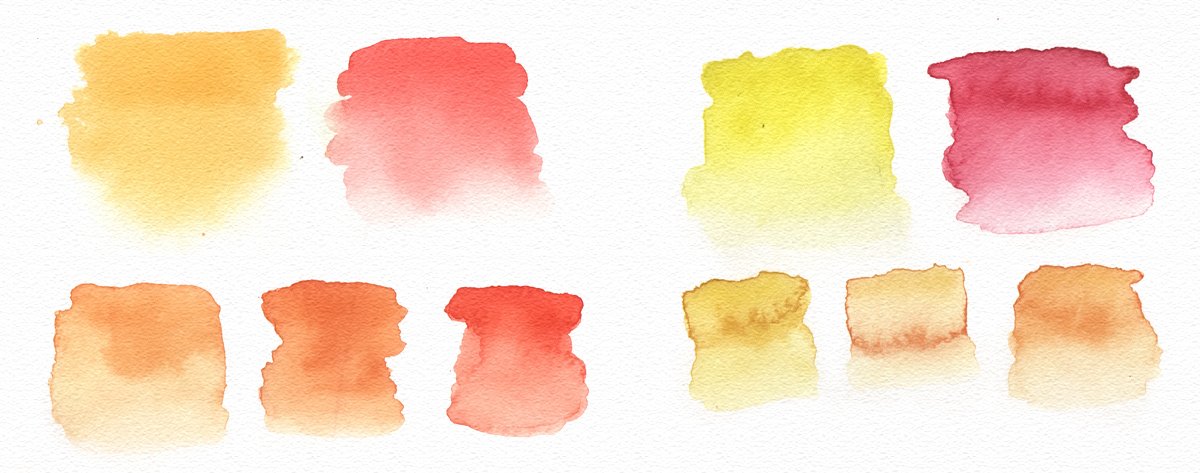

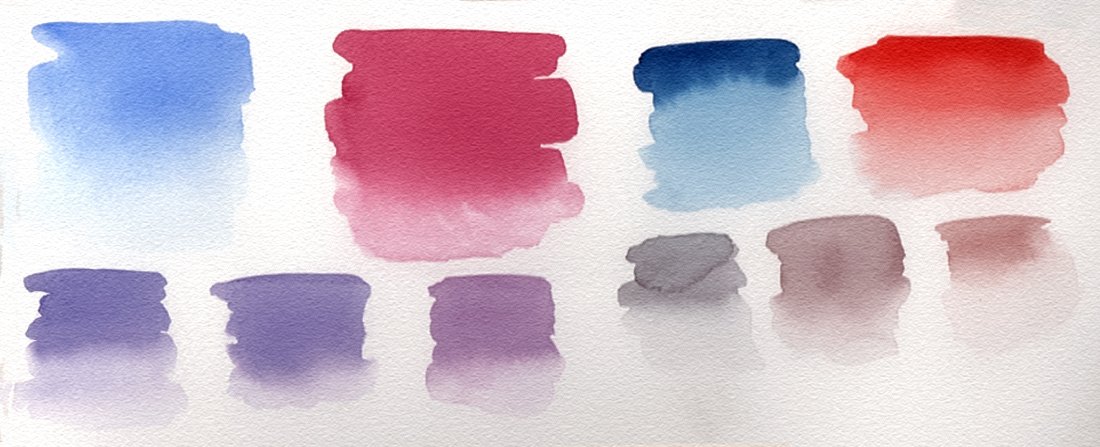

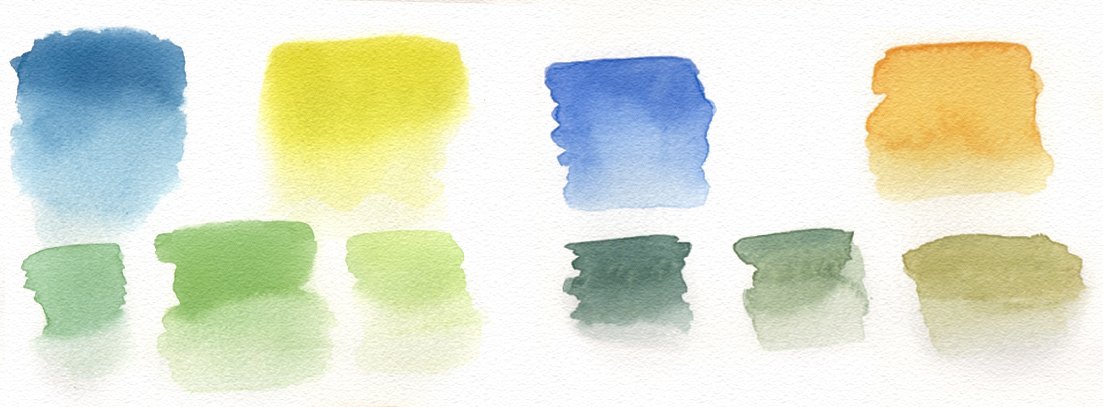

Chromatic grays obtained from a primary color and its complementary secondary color

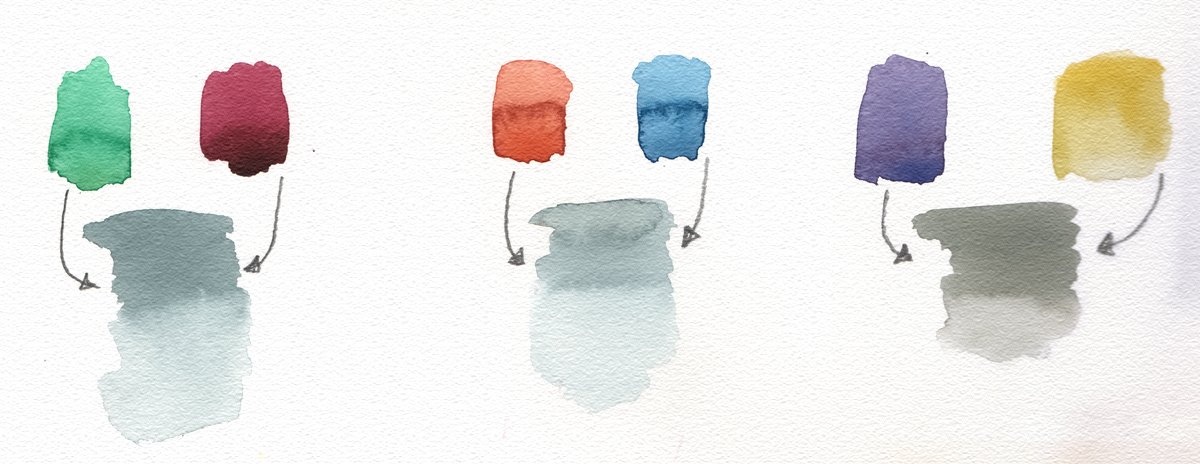

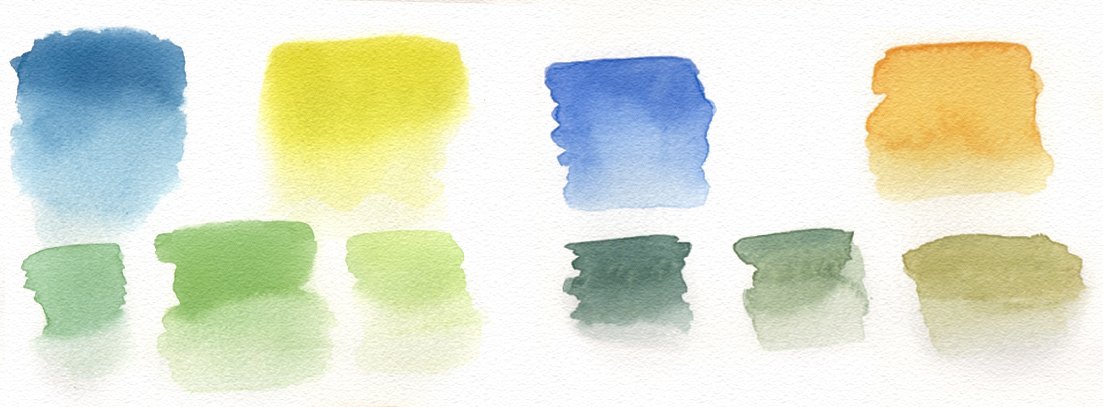

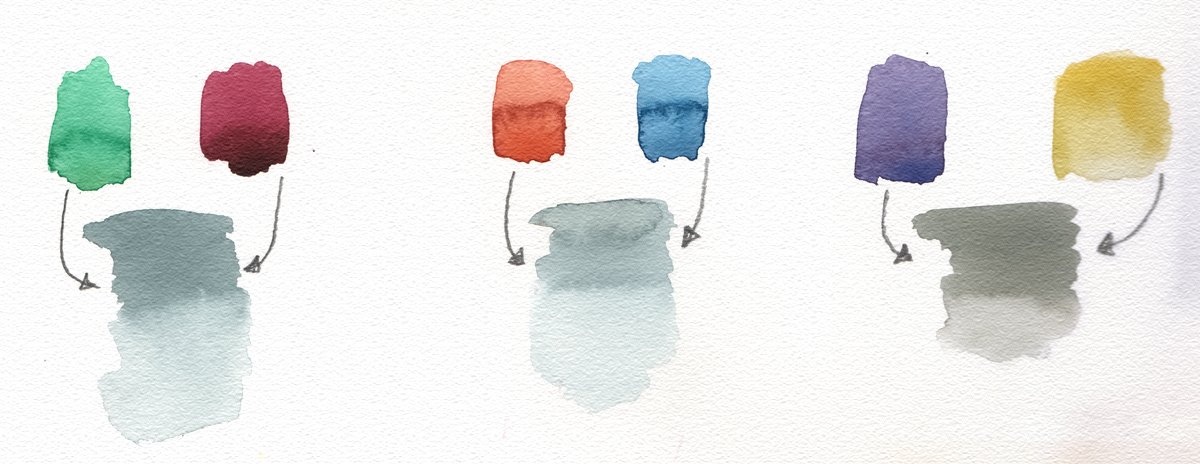

Special features when mixing primaries

We have already mentioned that the paint colors we buy from manufacturers are not pure; they always contain minimal traces of some other color. This is something we must take into account if we want our mixtures to be more effective. Prussian blue, for example, contains a hint of green, and so does lemon yellow, so mixing them together will give intense, luminous greens. However, if we mix ultramarine blue and golden yellow, we will get a dull green, as these two colors contain red, which, being complementary to green, "kills" the color. Another example: the mixture of cadmium red and prussian blue, which contain yellow, gives us an impure shade of violet, very brownish; to obtain intense and saturated violets, it is best to mix ultramarine blue with alizarin carmine, a red that has blue components. Another red, cadmium red, has yellow components; since golden yellow contains a hint of red, mixing it will give very pure oranges. On the contrary, the mixture of lemon yellow with alizarin carmine will give us impure oranges, very brownish.

Below I show you some examples, but I encourage you to try it if you have tubes or godets of these colors.

On the left, prussian blue+lemon yellow; on the right, ultramarine blue+chromium yellow deep

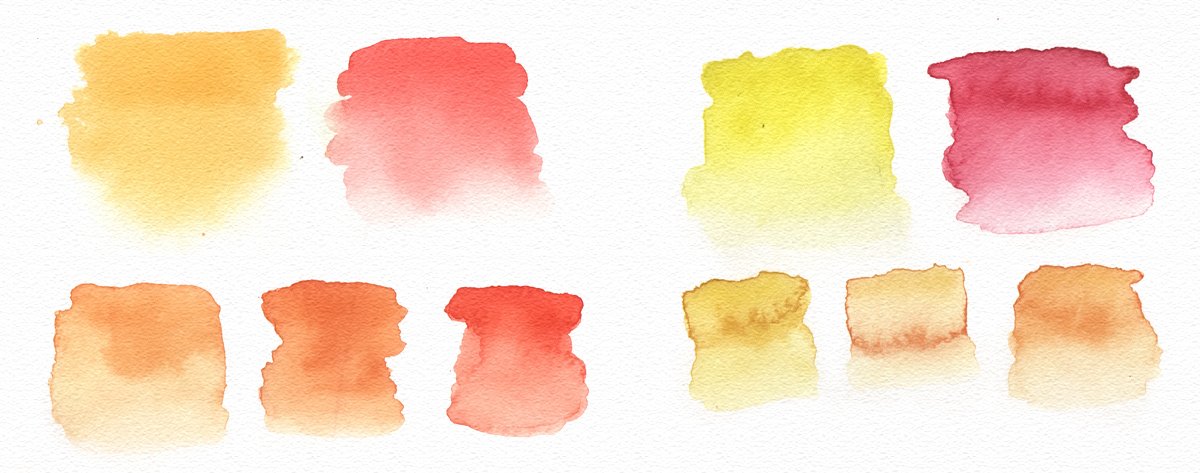

On the left, cadmium red+chromium yellow deep; on the right, crimson+lemon yellow

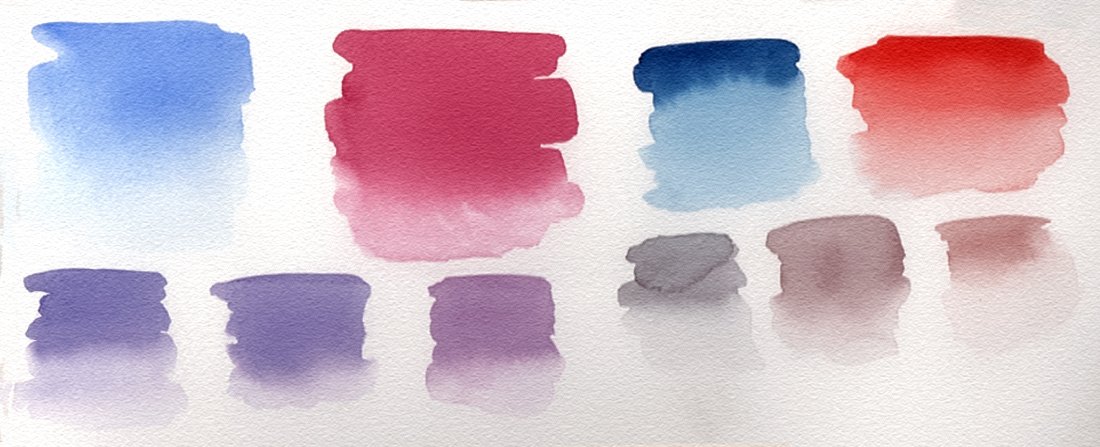

On the left, ultramarine blue+crimson; on the right, prussian blue+cadmium red

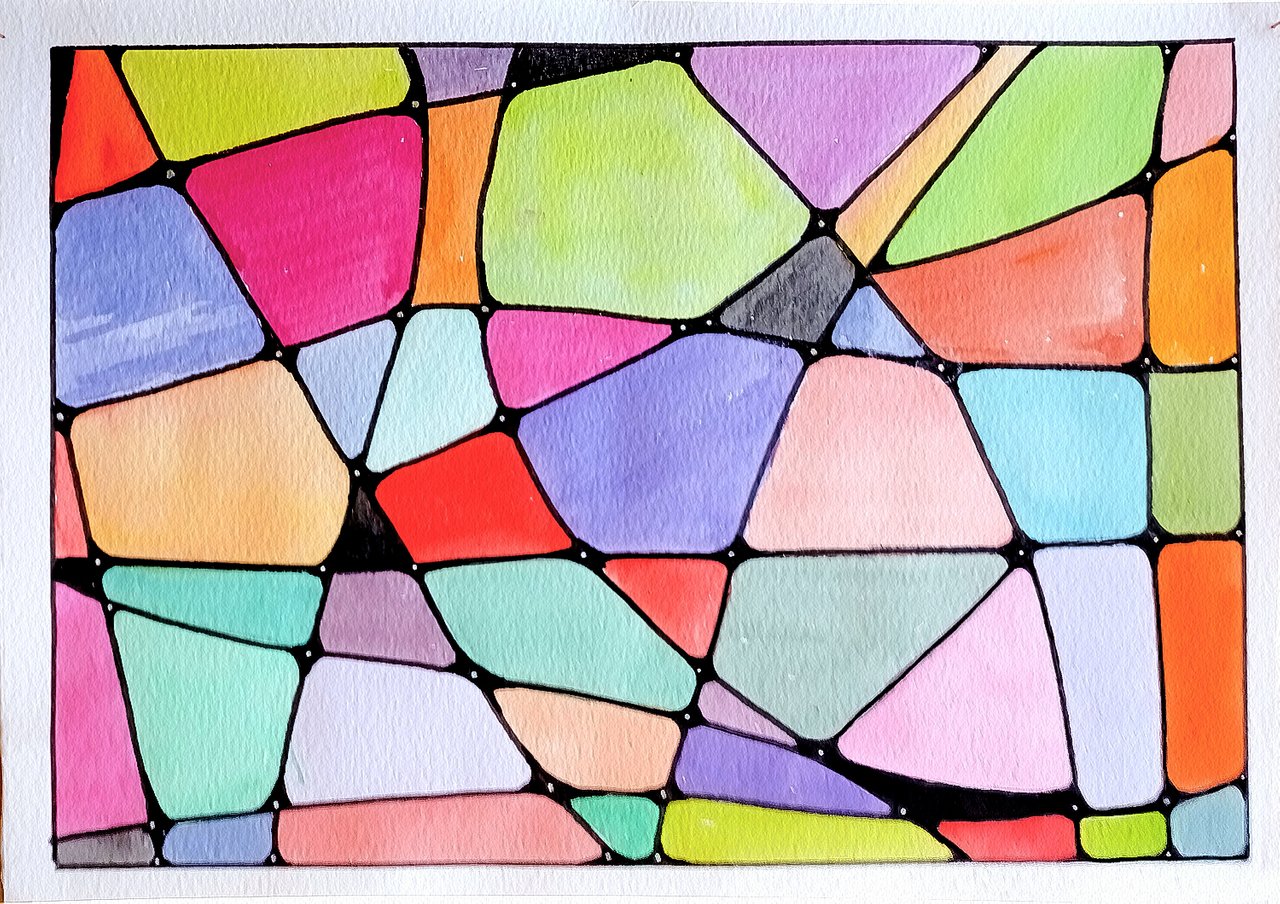

EXERCISE WITH SECONDARY COLORS

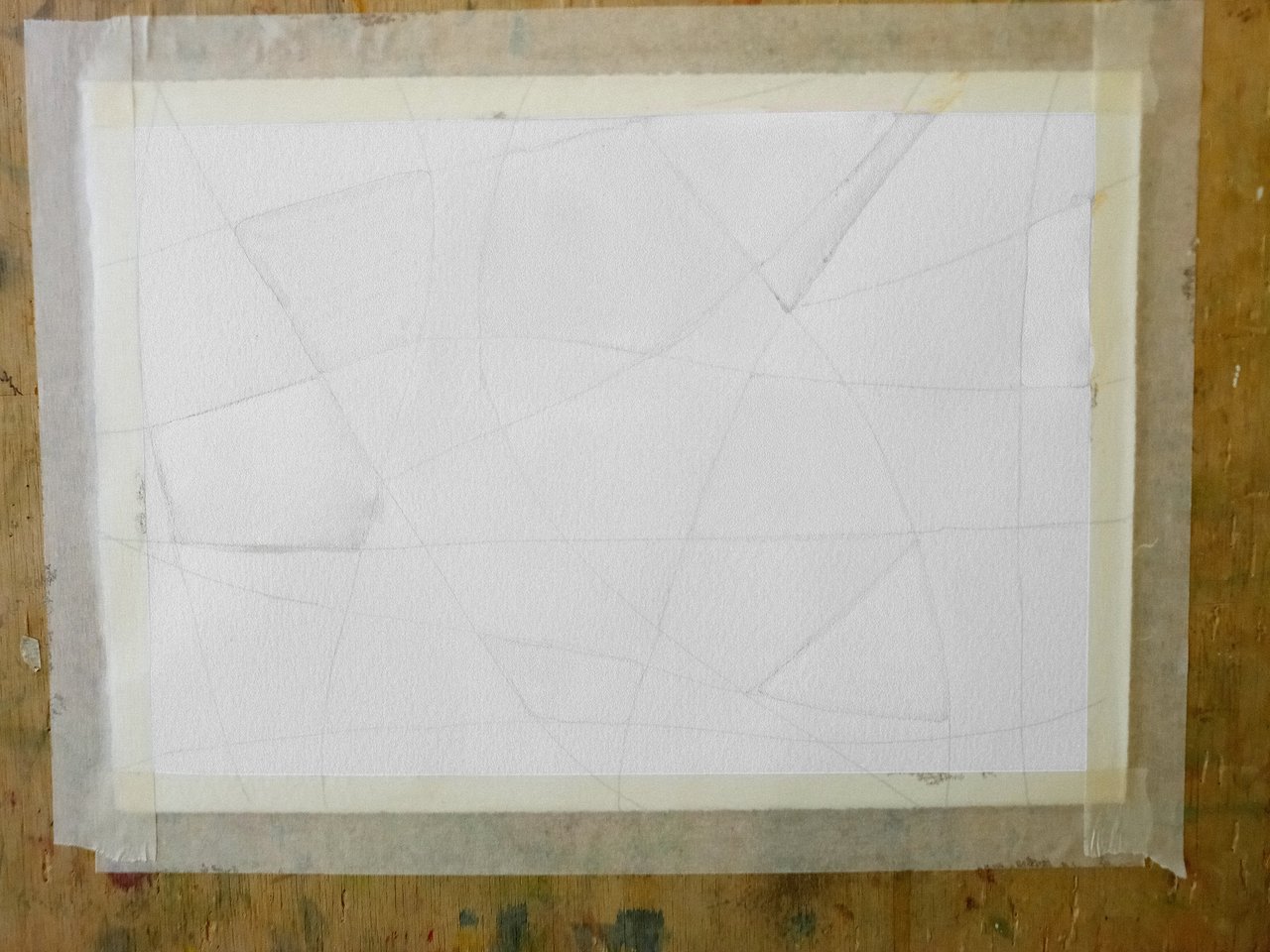

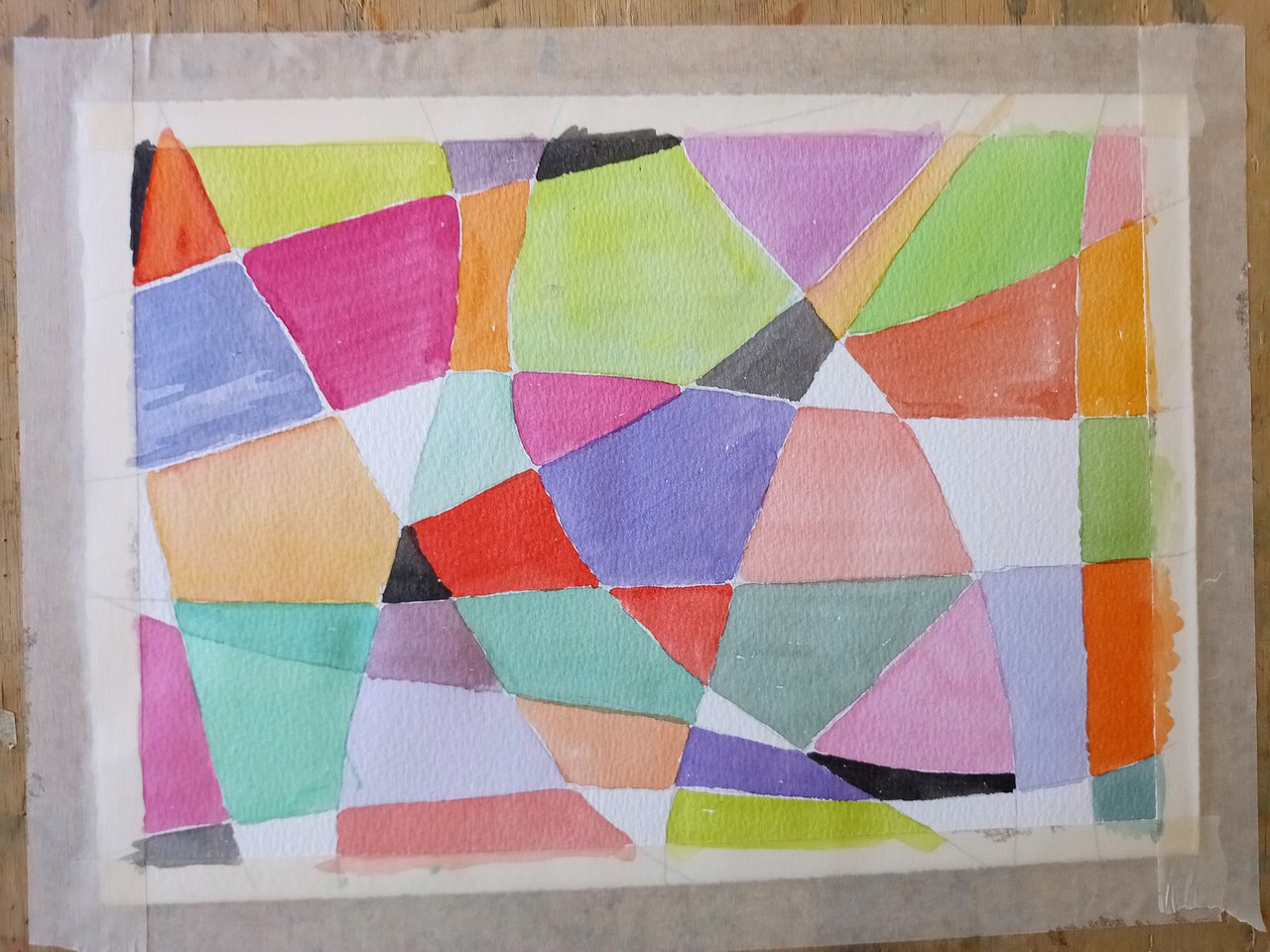

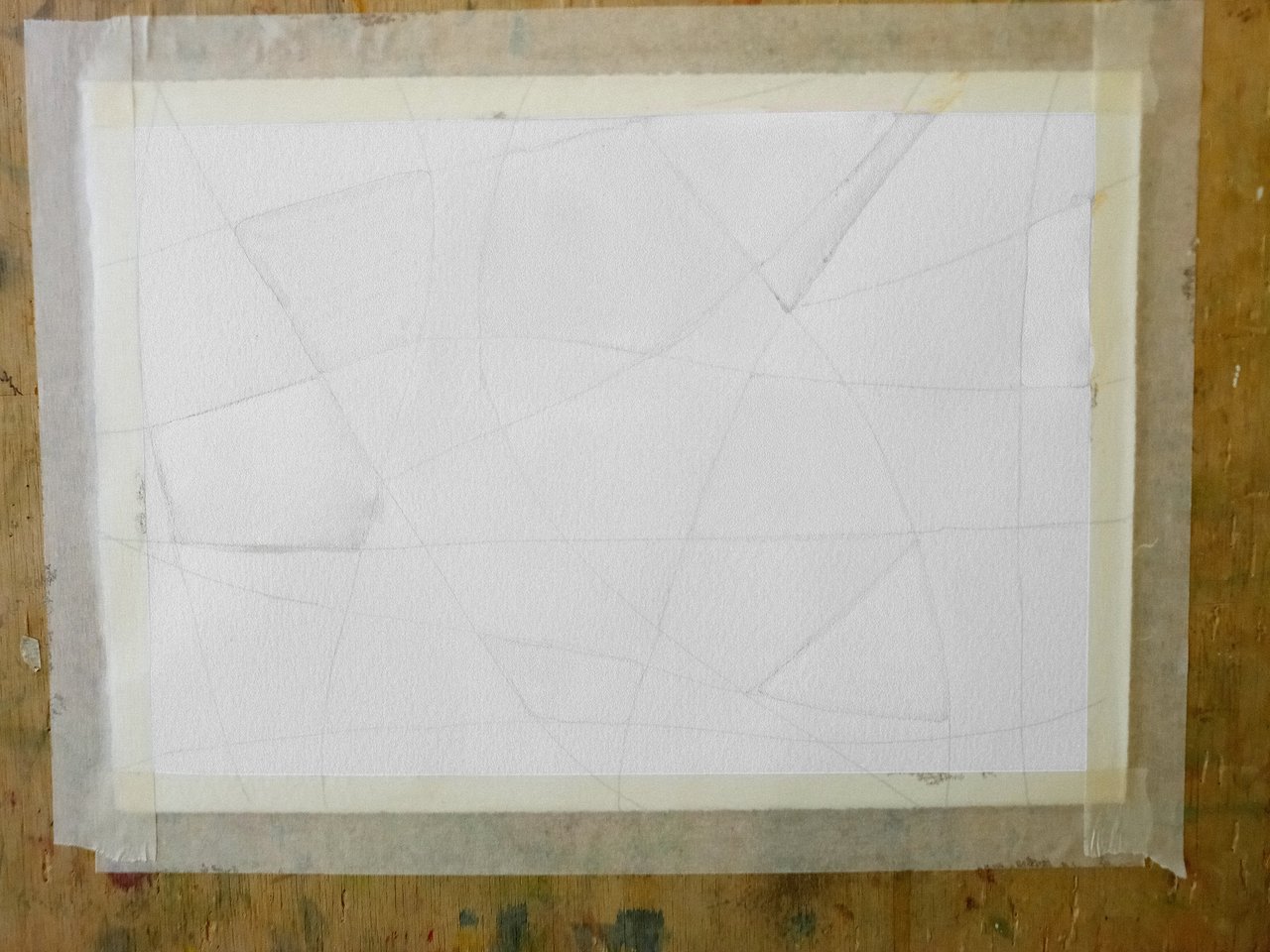

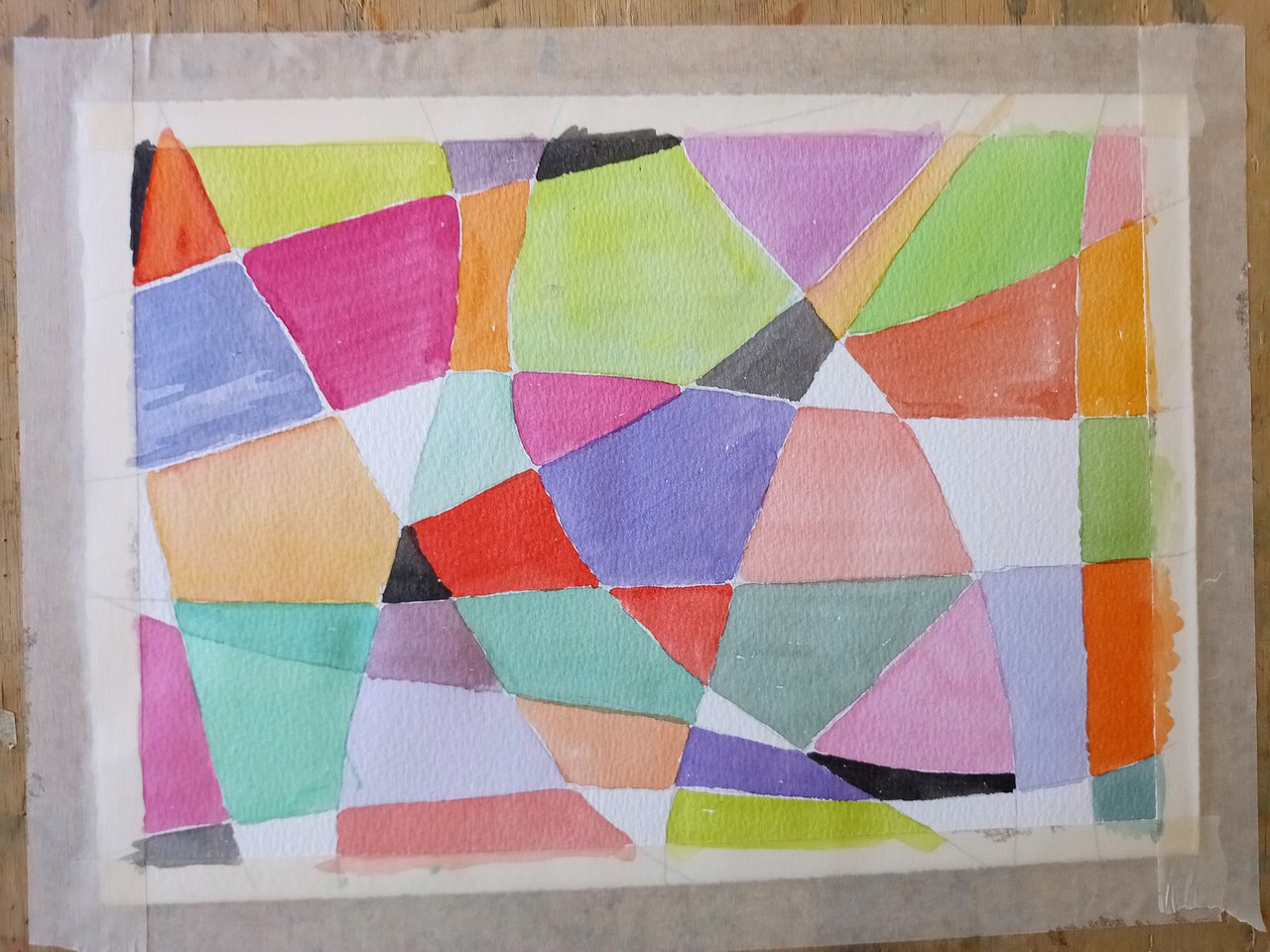

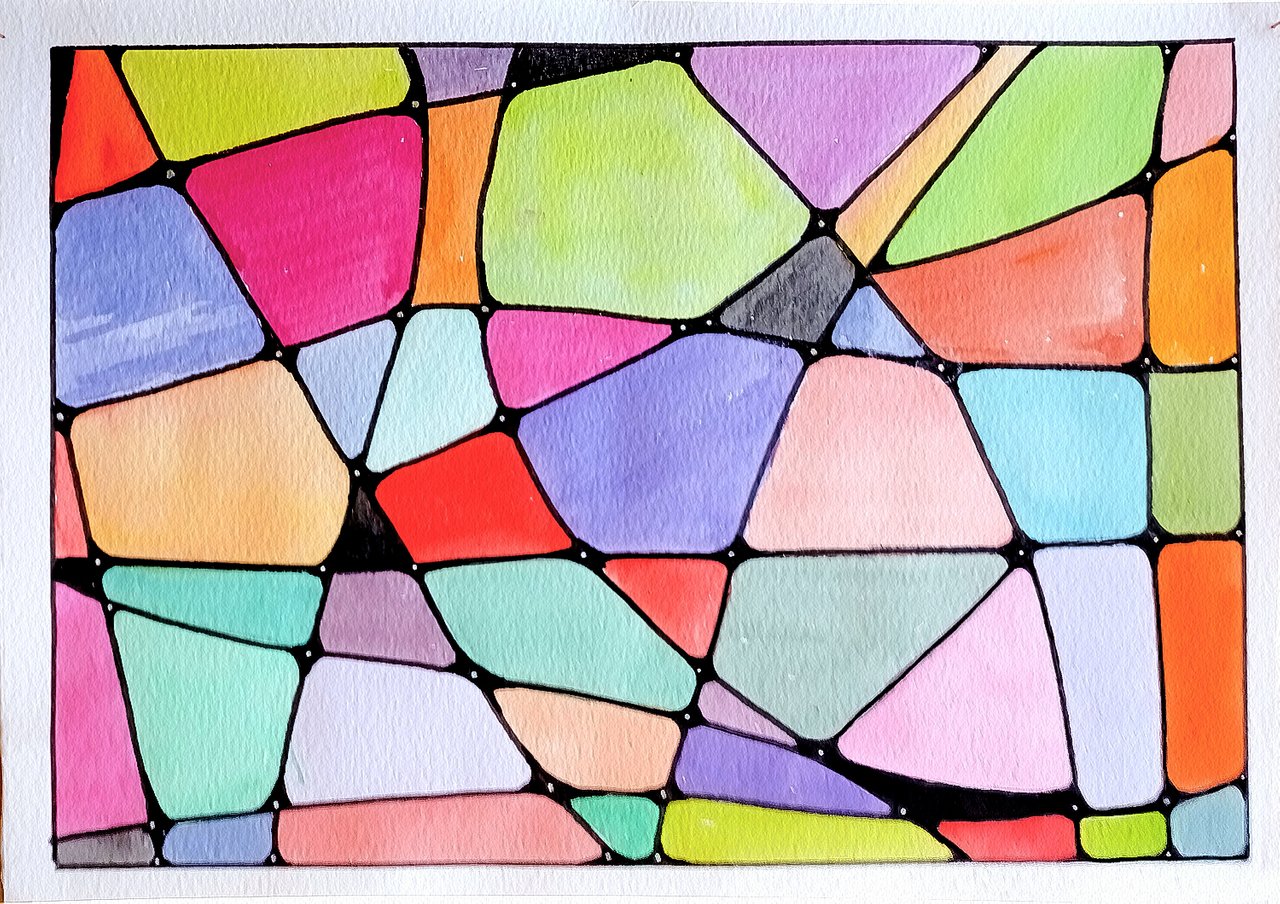

As in the previous exercise, we draw seven crosses in the space of the paper and extend their ends forming intersecting lines. Thus we are left with the surface of the paper divided into many compartments that we will fill with a variety of secondary colors.

Some of the compartments are filled directly with primary colors, with more or less intensity (that is, more or less water). Here we can also try different shades of blue, yellow and red to obtain brighter or duller and browner secondaries, as indicated above. We leave other empty spaces to be filled directly with secondary colors.

When the paint has dried, we give transparent layers of colors on top of the primaries to form the secondaries by transparencies. The rest of the spaces are filled with secondary colors obtained by mixing on the palette.

We fill some spaces, not too big, with an almost black color resulting from mixing the three primaries in equal parts.

We eliminate the pencil lines by painting over them with a marker. We will have a very colorful abstract work.

For the elaboration of this article, I have used the books Pintando a la acuarela, by Juan T. Comamala and El gran libro de la acuarela, by J. M. Parramón, apart from my own experience and some data from the ttamayo workshop website.

En el ejercicio anterior trabajamos con los colores primarios, aprendimos a aclararlos y oscurecerlos. En esta ocasión, vamos a practicar con los colores secundarios.

Antes, hay que hacer una pequeña aclaración. La teoría del color nos dice que los primarios son aquellos colores que no se pueden obtener de la mezcla de otros colores, y habla del magenta, el azul cían y el amarillo. Pero, a lo largo de los siglos, los artistas no se dedicaron a pensar en el color de forma teórica y conceptual, sino que fue con la práctica, a base de oficio, como fueron observando el comportamiento de los distintos colores. Así que, tradicionalmente, los pintores han usado como colores primarios diversas tonalidades de rojos, amarillos y azules. Y de ahí que, en distintos manuales de pintura y sitios de internet, nos encontremos con tríadas de primarios que difieren entre sí: que si carmín, que si magenta, que si cían, que si azul de prusia... Eso sí, cualesquieran que sean los tres que se elijan, quedan equidistantes en la rueda de color. Si recordáis, yo, por ejemplo, recomendaba en el anterior post usar el azul cerúleo, el amarillo cadmio medio y el carmín o el rojo de alizarina. Por último, resulta que, además, los colores comercializados por los fabricantes tampoco son exactamente puros en ese sentido teórico.

Los colores secundarios

Pero entremos ya en materia con los colores secundarios. Los secundarios son aquellos colores que se obtienen cuando se mezclan dos primarios en cantidades iguales. Así tenemos que azul y amarillo nos da verde; la mezcla de amarillo y rojo, naranja; y que del azul y el rojo obtenemos el violeta. La pureza o luminosidad del color obtenido dependerá del matiz del azul, rojo o amarillo utilizado como primario. En realidad, se puede producir una gran variedad de colores secundarios según mezclemos los primarios, y que entrarían en alguna de las categorías de verde, naranja y violeta. Para saber cuáles son exactamente los colores secundarios debemos considerar que éstos deben ser los complementarios exactos de los colores primarios.

Colores complementarios

Cada uno de los tres colores secundarios se considera, a su vez, complementario de uno de los primarios, precisamente de aquel que no se ha usado para su composición. De este modo tenemos que el verde es complementario del rojo, el naranja del azul y el violeta del amarillo. Los colores complementarios se encuentran en sitios opuestos dentro del circulo cromático y son los menos afines entre sí. Por eso son colores que contrastan mucho, o que se pueden emplear para conseguir grises cromáticos, por ejemplo.

Grises cromáticos obtenidos a partir de un color primario y su color secundario complementario

Particularidades a la hora de mezclar los primarios

Ya hemos mencionado que los colores de pintura que compramos a los fabricantes no son puros; siempre contienen trazas mínimas de algún otro color. Esto es algo que debemos tener en cuenta si queremos que nuestras mezclas sean más eficaces. El azul de prusia, por ejemplo, contiene una pizca de verde, y el amarillo limón también, así que su mezcla dará verdes intensos y luminosos. Sin embargo, si mezclamos azul ultramar y amarillo oro, obtendremos un verde apagado, ya que esos dos colores contienen rojo, que, al ser complementario del verde, "mata" el color. Otro ejemplo: la mezcla de rojo de cadmio y azul de prusia, que contienen amarillo, nos da un tono impuro de violeta, muy parduzco; para conseguir violetas intensos y saturados, lo mejor es mezclar azul de ultramar con carmín de alizarina, un rojo que tiene componentes de azul. Otro rojo, el de cadmio, tiene componentes de amarillo; como el amarillo oro contiene una pizca de rojo, su mezcla dará naranjas muy puros. Al contrario, la mezcla de amarillo limón con el carmín de alizarina nos dará naranjas impuros, muy pardos.

A continuación os muestro unos ejemplos, pero os animo a que hagáis la prueba si disponéis de tubos o godets de estos colores.

A la izquierda, azul de prusia+amarillo limón; a la derecha, azul de ultramar+amarillo cromo oscuro

A la izquierda, rojo cadmio+amarillo cromo oscuro; a la derecha, carmín+amarillo limón

A la izquierda, azul de ultramar+carmín; a la derecha, azul de prusia y rojo cadmio

EJERCICIO CON LOS COLORES SECUNDARIOS

Como en el ejercicio anterior, trazamos siete cruces en el espacio del papel y prolongamos sus brazos. Así nos queda la superficie del papel dividida en muchos compartimentos que rellenaremos con una variedad de secundarios.

Rellenamos algunos de los compartimentos directamente con colores primarios, con más o menos intensidad (es decir, con más o menos agua). Aquí podemos jugar también con distintos matices de azul, amarillo y rojo para obtener secundarios más vivos o más apagados y parduzcos, como hemos indicado antes. Dejamos otros espacios vacios para llenarlos directamente con colores secundarios.

Cuando la pintura se haya secado, damos capas transparentes de colores encima de los colores primarios para formar los secundarios por transparencias. El resto de espacios los rellenamos colores secundarios obtenidos mediante mezcla en la paleta.

Llenamos algunos espacios, no muy grandes, con un color casi negro que resulta de mezclar en partes iguales los tres primarios.

Eliminamos las lineas de lápiz pintando encima con un rotulador. Nos quedará una obra abstracta muy colorista.

Para la elaboración de este artículo, he utilizado el libro Pintando a la acuarela, de Juan T. Comamala y El gran libro de la acuarela, de J. M. Parramón, además de mi propia experiencia y algunos datos extraídos de la página web del taller ttamayo.

I take this opportunity to recommend you to visit the art classes of @jorgevandeperre and @fumansiu, who are also part of the #woxartschool initiative.

I want to give special thanks to @stef1, who suggested me to join this project, and @xpilar, whose support makes this kind of initiatives possible.