The Short Chronology is a realignment of ancient history advocated by Gunnar Heinsohn (1991), Lynn E. Rose (1999) and Emmet Sweeney (2008, 2007a, 2006, 2007b), championed by Charles Ginenthal (2003, 2009, 2010, 2013) and others, and inspired by the pioneering work of Immanuel Velikovsky (1952, 1960, 1977, 1978).

The Current Consensus

The prehistory of Britain and Ireland as it is currently espoused by mainstream archaeologists may be summarized as follows, with dates rounded to the nearest millennium or century:

Around 10 000 BCE the last glacial period—known in Britain as the Devensian and in Ireland as the Midlandian—came to an end. As the ice sheets retreated, flora and fauna recolonized the two islands and extensive afforestation occurred.

Between 9000 and 4000 BCE Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) hunter-gatherers arrived in small numbers from the continent and established numerous settlements, most of them in close proximity to the sea or inland waterways. These are possibly the earliest known inhabitants of Ireland (but see Dowd & Carden 2016 for a divergent opinion), and though earlier Palaeolithic inhabitants of Britain are attested, it is thought that both islands were completely depopulated prior to the arrival of these post-glacial migrants.

The Neolithic, or New Stone Age, flourished between 4000 and 2400 BCE. It was characterized by the introduction of agriculture, which resulted in largescale deforestation and a significant rise in population. The first farmers also introduced pottery. They are best known, however, for their construction of thousands of megalithic monuments. Of the latter, Stonehenge in Britain and Newgrange in Ireland are the most notable.

The Bronze Age—2400 to 700 BCE—saw the introduction of metallurgy. This period has left us a wealth of artifacts made from copper, bronze (an alloy of copper and tin), gold and silver. Local sources of these metals included the tin mines of Cornwall and the copper mines of Ross Island in County Kerry. The earliest phase of the Bronze Age—the Chalcolithic or Copper Age—also saw the arrival of a new style of pottery and other manufactured goods known collectively as Bell-Beaker ware.

The Iron Age, which, roughly speaking, covers the period between 700 BCE and 400 CE, is associated with the appearance of Celtic culture and the introduction of iron metallurgy, including carburized iron (steel). The end of the Iron Age is marked by the introduction of Christianity and the appearance of written records.

It is widely, though not universally, accepted that the pre-Celtic peoples who inhabited these islands for about seven millennia before the Iron Age spoke non-Indo-European languages.

The accuracy of this brief outline can be confirmed by consulting any reputable text (Ó Cróinín 2008) or online source (Wikipedia). Although this model has been staunchly defended by the scholarly establishment for nearly half a century, it is not without its problems. Three problems in particular are so significant that they are even acknowledged by the establishment. These are the Celtic Problem, the Genetic Problem and the Language Problem.

The Celtic Problem

The first of these three outstanding problems—“the thorny question of the manner and date of the coming of the Celts” (Waddell 2000:5)—has been stated succinctly by John Waddell in the following terms:

It has long been believed that the Celtic languages ... are descended from an ancestral language-family which developed in a Continental homeland from whence its speakers spread to ... Britain and Ireland ... The problem with such assertions is that Irish prehistoric archaeology reveals no trace whatever of any significant incursion of new peoples ... There is simply no archaeological trace of the large-scale immigration necessary not just to implant a new language but to eradicate virtually all traces of the pre-existing language as well. (Waddell 2000:288)

This problem has led to a rift between linguists and archaeologists. The former insist that the Celtic languages must have been brought to these islands by migrating Celts in the last millennium of the pre-Christian era, while the latter have hypothesized that the Celtic languages somehow diffused here as a result of centuries of cultural and economic contact with the Continent! (Waddell 2000:288) This strained theory has recently led to the oft-repeated notion that the Celtic invasions recorded in our native manuscripts are myth, not history:

Barry Raftery, professor of Celtic archaeology at University College Dublin, admits an enormous problem in justifying his subject: there is no archaeological evidence for a Celtic invasion of Ireland ... Over the period from about 450 BC to AD 450 when it is commonly agreed by scholars that there were Celtic societies and civilizations in western and central Europe, hardly any material evidence has been found here to substantiate the notion of Celtic Ireland. (Gillespie 2006)

It is hardly credible that Mesolithic hunter-gathers, who lived eight thousand years ago and cannot have been very numerous, should have left an abundance of archaeological evidence testifying to their existence, while the Celts, who lived less than three thousand years ago and were so numerous they not only implanted their language but eradicated all traces of the pre-existing language, should have left scarcely any material evidence to substantiate their very existence.

The Genetic Problem

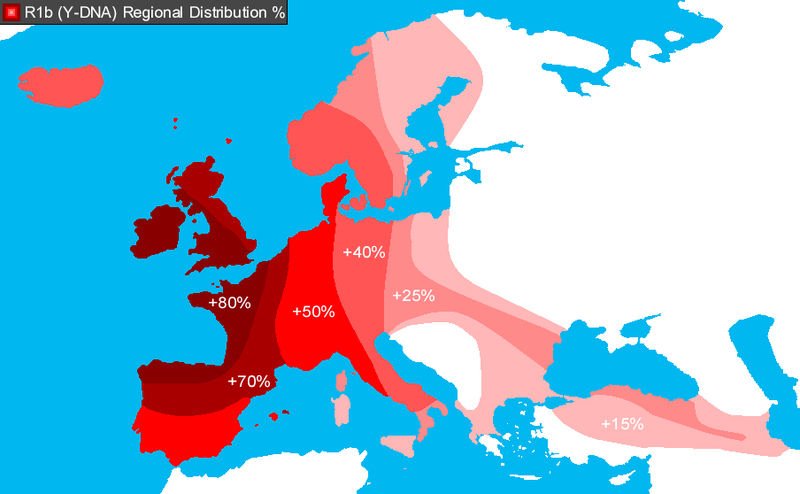

In the last few decades developments in the field of genetics have revolutionized our understanding of how early humans migrated out of Africa and populated the world. It was hoped that genetic studies of the British and the Irish would finally answer the question: Who were the Celts? But these hopes have not been realized: if anything, DNA studies have only exacerbated the Celtic problem. The genetic profile of the inhabitants of Britain and Ireland was largely established by the earliest settlers: there were no significant genetic shifts that could be attributed to Celtic invaders in the Early Iron Age. One study by a team from Trinity College Dublin was particularly interested in the genetic evidence for large-scale Celtic incursions around this time, but they found no such evidence:

Previous studies indicated particular affinities within the Atlantic zone of Europe on the basis of the distribution of both the Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b ... and the mtDNA haplogroup V ... During the last glaciation, human habitation is thought to have been largely restricted to refugial areas in southern Europe; one of the most important of these is likely to have been in southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula ... The recolonization of western Europe from an Iberian refugium after the retreat of the ice sheets ~15,000 years ago could explain the common genetic legacy in the area. An alternative but not mutually exclusive model would place Atlantic fringe populations at the “Mesolithic” extreme of a Neolithic demic expansion into Europe from the Near East.

In any event, the preservation of this signal within the Atlantic arc suggests that this region was relatively undisturbed by subsequent migrations across the continent ... Cunliffe (2001) has used Braudel’s term, the “longue durée,” to describe the long-term sedimentation of traditions on the Atlantic façade, which he suggests may stem from the late Mesolithic period, perhaps even predating the arrival of agriculture in the region. Our results support the view that the genetic legacy, at least, of the region may trace back this far and perhaps even to the earliest settlements following recolonization after the Last Glacial Maximum ...

What seems clear is that neither the mtDNA pattern nor that of the Y-chromosome markers supports a substantially central European Iron Age origin for most Celtic speakers—or former Celtic speakers—of the Atlantic façade. The affinities of the areas where Celtic languages are spoken, or were formerly spoken, are generally with other regions in the Atlantic zone, from northern Spain to northern Britain. Although some level of Iron Age immigration into Britain and Ireland could probably never be ruled out by the use of modern genetic data, these results point toward a distinctive Atlantic genetic heritage with roots in the processes at the end of the last Ice Age. (McEvoy et al 2004 )

Genetically speaking, the Celts have proved to be an elusive race. Geneticists have found it impossible to identify any such race or differentiate them from the pre-Celtic inhabitants of western Europe:

The identity of the “Celts” has played an integral role in understandings of the Iron Age and the more recent socio-political history of Europe. However, the terms and attitudes which have been in place since the 19th century have created a field of research characterized by assumptions about a “people” and a culture. Previous study of the “Celts” has been conducted in three main areas—genetics, linguistics, and material culture from the archaeological record. Through the reassessment of these three fields, substantial divergence in the patterns and trends between fields, as well as the highly regional nature of the evidence has been revealed within the vast interconnected trade and communication network that developed in Iron Age Europe. As a result, the unitary phenomenon identified under the term “Celts” is actually that network. This paper argues that “Celtic” should be redefined as the label for that trade and communication network, not as a label for a group, culture, or people, enabling the establishment of new identities for the regional populations of the European Iron Age. (Donnelly 2015)

These and similar findings from several other genetic studies have only strengthened the idea that we Irish are not Celts after all and that there never was a Celtic invasion of these islands. This runs counter to our longstanding traditions—written as well as oral—and the inescapable fact that our native language is Celtic.

The Language Problem

We have already touched upon the language problem. Most linguists insist that the Celtic languages emerged from an ancestral offspring of Indo-European no earlier than about 1200 BCE:

At what point Celtic, or better, “protoceltic” languages first became distinguishable from other Indo-European languages is debatable. It has been suggested that this may already have happened by the beginning of the Neolithic period, but most linguists would prefer a later date, towards the end of the second millennium B.C. or even later. (Chadwick & Cunliffe 1997)

If there were people living in Britain and Ireland for six or seven millennia prior to this, then they must have spoken pre-Celtic, and probably pre-Indo-European, languages. But what languages these were no one can say, because no trace of them has survived.

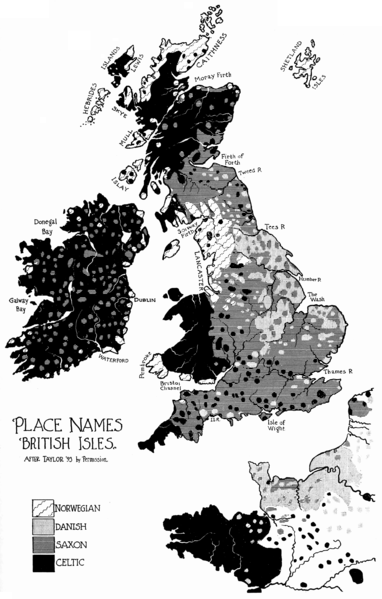

If Ireland was home to some three hundred generations of pre-Celtic speakers, it is only reasonable to assume that these people would have bestowed names on the natural features of the landscape: every river, lake, mountain, estuary and promontory would have acquired a native name. Is it credible that the arrival of the Celtic languages—however this might have happened—led to the eradication of every single one of these native names? Nevertheless, it is a fact that today there is not a single toponym in Ireland or Britain that can be shown to be indisputably pre-Celtic. Those that are not undeniably Celtic are invariably post-Celtic. And not a trace remains of the pre-Celtic languages that were supposedly spoken here for millennia. In vain do linguists search the vocabularies of Welsh and Irish for pre-Celtic borrowings.

Admittedly, a few scholars have hypothesized that traces of a pre-Celtic language—or, to speak technically, a pre-Goidelic substrate—have survived in a handful of Irish words and toponyms. One Irish Celticist, Gearóid Mac Eoin, has asked the question: What Language was Spoken in Ireland Before Irish? But even he has been forced to concede that the case for a pre-Goidelic substrate has not yet been made:

It is true to say that Irish has not yet been reliably shown to contain any word, placename, personal name, or syntactic construction which has been convincingly credited to the language which preceded it in Ireland. (Mac Eoin 2007)

And if the lack of pre-Celtic toponyms is anomalous, so too is the complete absence of pre-Celtic personal names. Of the hundreds, or even thousands, of names that the pre-Celtic inhabitants must have bestowed on their own children, not one was not deemed worthy of retention when Celtic supplanted pre-Celtic. (But see Mac Eoin 2007:122, where he instances Bréifne, a toponym that came to used also as a girl’s name, as an Irish word of unknown etymology.)

Clearly, something is amiss.

A Lack of Consensus

As we have seen, archaeologists and geneticists have concluded from the evidence of their respective fields that there never was a Celtic race or a Celtic invasion of Britain or Ireland. But linguists have identified a Celtic family of languages, some of which became established in these islands to the total exclusion of all others. How could a foreign language arrive in a country and supplant the native languages without being brought there by foreign migrants who spoke that language? The only two possible explanations are equally problematical:

- Somehow the Celtic languages diffused from the Continent during the Iron Age via trade and other forms of cultural contact.

- At least some of the earlier post-glacial settlers were Celtic speakers.

The archaeologists looked for the Celts in the Iron Age but failed to find them:

R. A. S. Macalister asserted that this change [from a bronze-based technology to an iron-based one] was brought about by the immigration of Celtic peoples about 400 BC: the invading Celts subduing the aboriginal inhabitants with superior iron weapons. But there is no good archaeological evidence to support the theory of an influx of new peoples on any scale. (Waddell 2000:286)

The geneticists discovered that the gene pool of the Celtic regions was established in the early post-glacial era, and they concluded that the Celtic languages became established here much earlier than the Iron Age:

Languages geographically associated with the ancient Celts and modern insular-celtic languages all have a common southwest European origin. I have used the recent literature in several disciplines, and my own re-analysis, to ask when celtic languages moved from the european mainland to the British Isles, with which culture, and carried by how many people. My answers are (1) Neolithic, (2) Neolithic and (3) not many. (Oppenheimer 2006, Epilogue)

This scenario, however, is flatly rejected by the linguists:

Therefore we may assume that the mesolithic inhabitants of Ireland were not speakers of an Indo-European language. The traditionally accepted timeframe for Indo-European spread would also exclude the neolithic people who might have been admissible as possible Indo-Europeans under the [Colin] Renfrew model. If the first attestations of Indo-European languages in Anatolia, India, or Persia are datable to the first half of the second millennium B.C., even allowing for the fact that the first attestation is not necessarily contemporaneous with the introduction of the languages to those countries, the earliest possible date for the introduction of Indo-European to Ireland can be no earlier than that. In fact a date about the end of the second millennium B.C. could be considered as the earliest possible period for the Indo-Europeanisation of Ireland. (Mac Eoin 2007:115)

This echoes the opinion of the Irish scholar T F O’Rahilly, a linguist and a Celticist, who also rejected the notion that the Celtic family of languages could be as old as the Neolithic, or even the early Bronze Age:

Apart from other objections, which need not be stated here, it would be very difficult to accept [the] thesis that Celtic had already become a distinct dialect of Indo-European as early as 1900 B.C. (O’Rahilly 1946:431)

O’Rahilly, whom I have just quoted, was fond of the Irish saying Dall cách i gceird ar-oile, “which, freely interpreted, means that one generally makes a fool of oneself when one intrudes into a subject which is not one’s own.” (O’Rahilly 1946:vi) Archaeologists and geneticists would be well advised to keep this in mind when they presume to lecture linguists on the history of the Celtic languages.

To be continued.

References

- Nora Chadwick, Barry Cunliffe, The Celts, Penguin Books Ltd, London (1997), “Europe in the Late Bronze Age: The Origins of the Celts”

- Harriet Donnelly, “The Celtic Question: An Assessment of Identity Definition in the European Iron Age,” Archaeologies, Volume 11, Issue 2, August 2015, pp 272-299, Abstract

- Marion Dowd, Ruth F Carden, “First Evidence of a Late Upper Palaeolithic Human Presence in Ireland,” Quaternary Science Reviews, Volume 139, 1 May 2016, pp 158–163

- Paul Gillespie, The Irish Times, 29 July 2006

- Charles Ginenthal, Pillars of the Past, Volumes I-IV, Forest Hill, New York (2003, 2009, 2010, 2013)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Wie alt ist das Menschengeschlecht?: Stratigraphische Chronologie von der Steinzeit zur Eisenzeit, Mantis-Verlag, (1991)

- Gearóid Mac Eoin, “What Language was Spoken in Ireland Before Irish?”, in The Celtic Languages in Contact, Hildegard L C Tristram (editor), Potsdam University Press, Potsdam (2007)

- Brian McEvoy, Martin Richards, Peter Forster, Daniel G Bradley, “The Longue Durée of Genetic Ancestry: Multiple Genetic Marker Systems and Celtic Origins on the Atlantic Facade of Europe,” The American Journal of Human Genetics, October 2004, Volume 75, Issue 4, pp 693 – 702

- Dáibhí Ó Cróinín (Editor), _A New History of Ireland, Volume I, “Prehistoric and Early Ireland”, Oxford University Press, Oxford (2008)

- Stephen Oppenheimer, The Origins of the British, Constable & Robinson Ltd, London (2006)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946)

- Lynn E Rose, Sun, Moon, and Sothis: A Study of Calendars and Calendar Reforms in Ancient Egypt, Kronos Press, Deerfield Beech, Florida (1999)

- Emmet John Sweeney, Ages in Alignment, Volumes 1-4, Algora Publishing, New York (2008, 2007, 2006, 2007)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Ages in Chaos, Volumes 1, 2, 5, 4, Doubleday and Company, New York (1952, 1960, 1977, 1978), Volumes 3, 4 published online at The Velikovsky Archive

- John Waddell, The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland, Worldwell Ltd, Bray (2000)

Image Credits

- Ballymagany Lough, County Donegal, 24 December 2015: Public Domain

- Newgrange: Shira, Wikimedia Commons, GNU Free Documentation License

- Grianán of Aileach, County Donegal: Peter Homer, Standard YouTube License

- R1b-DNA-Distribution: Cadenas2008, Public Domain

- Origin of Place Names of the British Isles: Public Domain

- Robert Alexander Stewart Macalister - 1870-to-1950: Wikimedia Commons, Palestine Exploration Fund, Creative Commons

- Thomas Francis O’Rahilly: Source Unknown