Up to this point, I’ve tried to reveal the challenges associated with La Gonâve, including the land, cultural obstacles, poverty and so forth. I’ve also presented some ideas for how that could be improved, but nothing really comprehensive.

Today’s entry will be a bit detailed and more didactic than the others, but helpful for those interested in such things. It is imperative to go much deeper in my study of the land from a holistic perspective before actually laying out a design. This is where many become myopic, because earthworks and “building something” is, in many ways, more rewarding than studying it in the first place. But such myopia has resulted in poor designs that at least aren’t as efficient as they could be, and in some cases can result in catastrophic failures.

Tomorrow we’ll look more closely at some design ideas. Every landscape is different, so we can’t really just copy and paste from another location. But we’ll look at some designs to give us ideas of what we can do, and then will plan on conforming them to the context of Happy Dog once a more comprehensive analysis can be pursued.

The following day we’ll discuss composting, including the regenerative options of humanure. Thursday we will discuss a holistic model as a solution, with Friday being the final proposal. See, there is some light at the end of this tunnel.

Holistic Regeneration

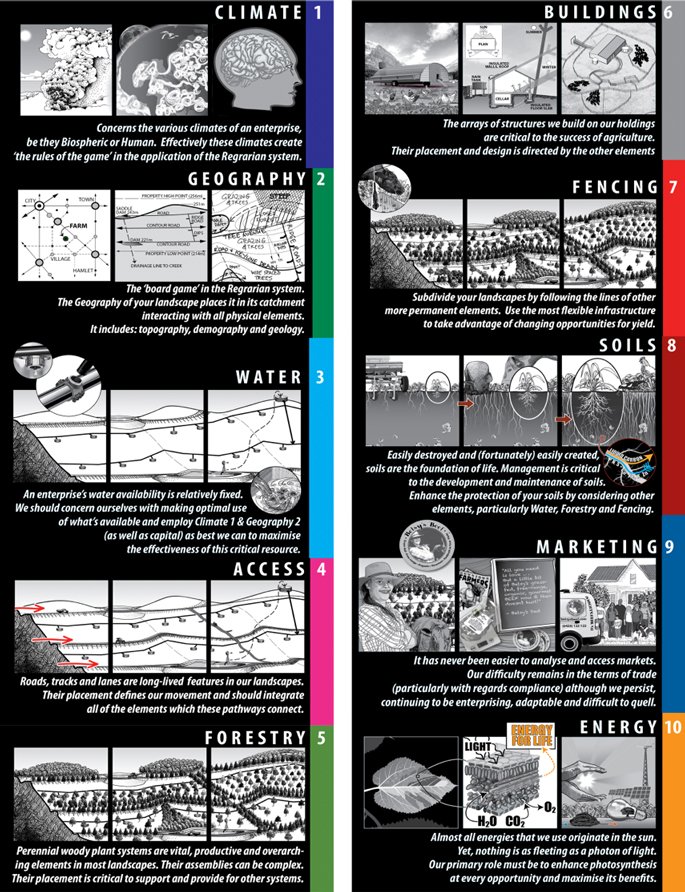

The approach we’ll be taking will correlate with P.A. Yeomans’ scale of permanence as adapted by Darren Doherty in the Regrarians® Platform. This will help us to line up the things we cannot change first, or that we can change the least, and make sure the aspects that follow work with what we’re given.

There’s a sense in which the way we manage land today is barbaric. We put in straight fences, tear things down, put buildings in un-holistic locations, etc., then we try to make the farm, ranch or other project fit what we’ve done. But all of these are temporary and should complement the lay of the land and its greatest function rather than attempting to make the function and form fit the more temporary aspects of the project.

Remember, your buildings start degenerating from the moment they’re built. The land can be set on a regenerative path that no longer needs you, if done well. So it helps to consider the best design for the land before deciding where to put our buildings.

This means that the climate, geography and water flow should be considered before we put choose a site for one single building. And all of these should be considered before we put a single fencepost in the ground. Actually, fences are one of the last things we design.

Having laid that out, we have to deal with the fact that buildings are usually already present, so we work with what we have. We’ll go over some of these very briefly, and spend more time on water and forestry (which includes all plants, as well as livestock).

Climate

Climate includes various aspects, including the human climate, political and bureaucratic as well as meteorology. While the human factor may be changed, when designing we have what we have to work with. And changing people isn’t our goal initially, though we always hope to influence them in a positive way. Our initial goal must be to understand them and work within their context as much as possible.

Up to this point, I have largely relayed much of the human climate involved. More details can be laid out once we’ve been able to meet with the landowners to discuss how they might want to proceed, as well as investigate the bureaucratic hurdles.

Haiti is tropical. Rainfall on La Gonâve is about 54” a year. It’s hot and humid most of the time, but especially during hurricane season. As an example, today is supposed to be 34 C for the high and 26 C for the low. This may be based on somewhere on the mainland though, since it’s relatively difficult to get good data on La Gonâve. Winter temperatures are just a few degrees lower.

Happy Dog is noticeably nicer though, as a result of the higher elevation and cooling breezes that are enjoyed there. In many ways it’s greener too, though the windward side of the island boasts a lot of flora.

There is still a lot of work to do regarding the bureaucratic challenges. Haiti is a nightmare in some ways, because you never know what you’ll get. But locals know how to get things done, so we’ll rely on them to help navigate those waters when it’s time.

For the region we’re focused on, the people are sparsely populated, with each working at least some acreage. Most of the land that I saw isn’t really managed (though that, too, can be a management strategy).

Geography

The island is largely too steep to do a lot with, though some terracing is possible. On the other hand, there is plenty of land that is sloped gradually enough to set up orchards, row crops, grazing and other efforts.

Generally, the soil is poor quality. It surprises many to find out that this is common in rain forest areas, where topsoil tends to be very shallow. But this can be remedied by getting a good groundcover going and increasing the organic matter in the soil. This will be part of the regenerative path we’d pursue.

Due to the steepness and the loss of vegetation to slow water flow, significant erosion is occurring. This includes both the loss of topsoil and the incising of channels as the flow increases and carries more debris. Perhaps the most degenerative things we see in any landscape is bare soil. Though the images show a decent amount of vegetation, it is mostly opportunistic and there is still a great deal of exposed soil.

Water

In some ways, water is the biggest issue on the island. It’s not a lack of rainfall, but a lack of retention. And, as noted above, the erosive factor released the water too quickly for it to be stored in the soil.

Springs and historically shallow water tables have dried up. It would be helpful to talk to someone that’s been around for a hundred years about what the springs looked like when they were young. My suspicion is that there were many springs along the valleys and slopes.

Water storage is not difficult. This includes both for watering and for domestic uses. But it takes work to get to the point where the water is slowed and stored, whether in cisterns or in the soil. Once the structure is in place, however, the effort becomes mostly passive, other than occasional maintenance and possible refinement.

Source

The water table varies considerably, between 30 and 60 meters. The following quote is taken from this entry on the Springer Link site. It also provides some geographical details that are helpful.

Île de la Gonâve is a 750-km2 island off the coast of Haiti. The depth to the water table ranges from less than 30 m in the Eocene and Upper Miocene limestones to over 60 m in the 300-m-thick Quaternary limestone. Annual precipitation ranges from 800–1,400 mm. Most precipitation is lost through evapotranspiration and there is virtually no surface water. Roughly estimated from chloride mass balance, about 4% of the precipitation recharges the karst aquifer. Cave pools and springs are a common source for water. Hand-dug wells provide water in coastal areas. Few productive wells have been drilled deeper than 60 m. Reconnaissance field analyses indicate that groundwater in the interior is a calcium-bicarbonate type, whereas water at the coast is a sodium-chloride type that exceeds World Health Organization recommended values for sodium and chloride. Tests for the presence of hydrogen sulfide-producing bacteria were negative in most drilled wells, but positive in cave pools, hand-dug wells, and most springs, indicating bacterial contamination of most water sources. Because of the difficulties in obtaining freshwater, the 110,000 inhabitants use an average of only 7 L per person per day.

Also helpful is information from the UN Development Programme. Though I tend to be mindful of concerning UN agendas, they have an incredible amount of data that can be helpful. Here you can see projections of decreased rainfall over the next 30+ years. I’ll comment below the quote.

Decreases in precipitation: precipitation is expected to decrease by 5.9-20% by 2030 and by 10.6-35.8% by 2060, with the greatest decreases also expected in the months of June or July. Agriculture on the hill lands which dominate the watersheds is principally rain-fed, and therefore highly vulnerable to variations in the timing of the rainfall rhythms which determine sowing and harvesting times.

The coincidence of increased temperatures and decreased precipitation, especially in June and July, is likely to impose particularly severe stresses on agricultural systems, especially given the highly degraded nature of soils and vegetation in the target watersheds. Climate change predictions for 2050 and beyond suggest that more than 50% of the total area of Haiti will be in danger of desertification due to climate variability and change.

This is a case where I believe that the statisticians have bought into their own narrative too much. It’s not that they necessarily don’t have the data to point the direction of the trend. It’s that they see the cause as external, failing to see the relationship between the local land, its flora, and changes in precipitation.

Orographic Cloud

We discussed this in some detail in the last entry, so do not need to belabor it here. Suffice it to say that when we destroy flora, we should expect things to change on a macro scale. In this case, there is ample evidence to expect an increase in precipitation to result from an increase in vegetation, specifically large canopy trees complemented by shorter mid-story trees.

It’s my position that by increasing the number of trees on the peaks and ridges of La Gonâve, that we will reverse this trend of decreasing rainfall and increasing desiccation.

Access

This is simply how we get from point A to point B. Often there is little design that goes into road and path placement. However, with some strategic design, our roads can become one of our greatest water control features as well as diminishing the erosion of the land.

We’ve all seen roads with deep cuts in them from rains. While, in some ways, this is unavoidable during a deluge, it can be controlled a great deal by placing roads according to our design up to this point, to complement the previous features and considerations. It’s a matter of using what we have and making sure we get to where we need to be as efficiently and effectively as possible.

Additional Considerations

The rest of the aspects of our scale of permanence will depend upon our design up to this point. It goes as follows, in this order.

- CLIMATE – You, Enterprise, Risk, Weather

- GEOGRAPHY – Landform, Components, Proximity

- WATER – Storage, Harvesting, Reticulation

- ACCESS – Roads, Tracks, Trails, Markets, Utilities, People

- FORESTRY – Blocks, Shelter, Savannah, Orchards, Natural

- BUILDINGS – Homes, Sheds, Portable, Yards

- FENCING – Permanent, Electric, Cross, Living

- SOILS – Planned Grazing, Minerals, Fertility, Crops

- ECONOMY – Analysis, Strategy, Value Chain

- ENERGY – Photosynthesis, Generation, Storage Climate

Obviously there is some overlap involved. However, by focusing on these in succession, we embrace the fact that some aspects are far more temporary than others, and strive to make the least permanent complement those that are more permanent, by nature.

I plan on going through this scale in more detail in a future series, but wanted to touch on it here in our context. Every context is so drastically different that our concentration on each of these aspects can demand varying degrees of attention. Where we have sweeping grasslands we aren’t nearly as worried about the lay of the land as in a case such as what we have on La Gonâve.

La Gonâve offers its own unique challenges because of the remoteness and steepness of the terrain. But there is plenty to work with, which we’ll focus on tomorrow.

Steemin' on,

Another Joe

Email notifications

Facebook

Twitter