It’s never too late to tell someone how you feel...until it is.

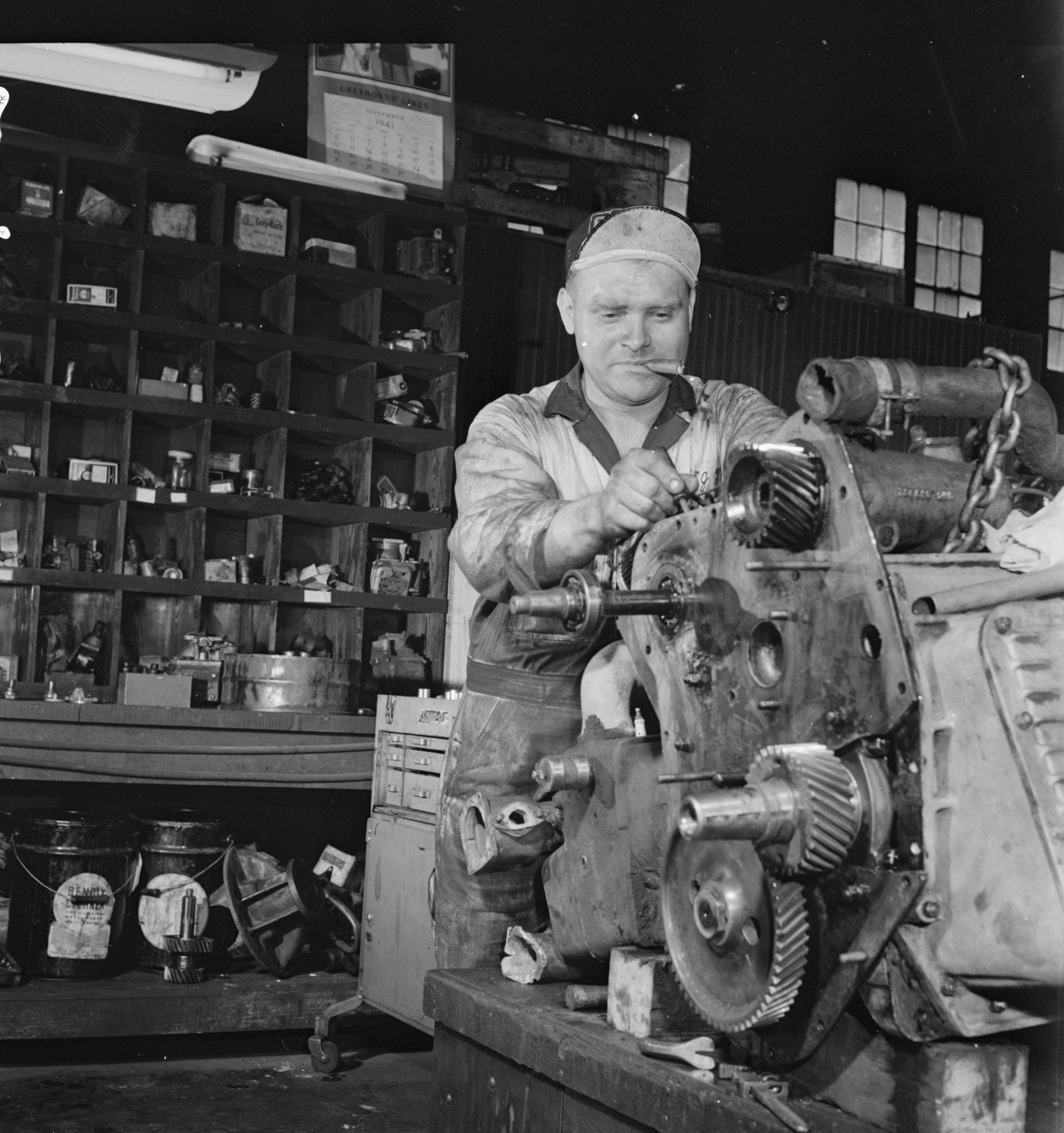

My grandfather was an exceptional man. He was like a father to my brothers and me. He was the ultimate family man, friend, and neighbor. He worked on cars most of the time, fixing them for anyone who needed help with it. Pay for the parts and he would handle the labor – even teach you how to fix it yourself. He would tinker with all sorts of other gadgets as well and was the first in the neighborhood to get a satellite dish back in the mid to late-80s – about a 14-foot wide monstrosity that was installed on top of the detached two-car garage.

*Not my grandfather. This image is public domain

My grandmother loved watching sports, so the satellite allowed her to search through hundreds of channels from across the country – and the world – to find any sporting event she wanted to see. If my brothers and I were playing outside, we always knew when she was channel-surfing because the dish would be swirling around in all of its mechanical glory. It would finally settle and the black mesh saucer would go silent, signaling that grandma had found something to enjoy for a few minutes. We would go inside and find her listening to baseball on the radio and watching tennis, football, or another baseball game on the television – as she walked back and forth to the kitchen while preparing her daily Italian feast.

As a child, I didn’t quite realize that my grandmother was a revolutionary. It took another fifteen years for me to truly understand that her viewing habits with the satellite dish were indeed the future. She was breaking that glass ceiling before the sand even made it to the furnace. She was, undeniably, a woman ahead of her time.

At a very young age, my grandfather began teaching us about collecting cans for recycling and taught us how to identify the aluminum ones with a magnet. He eventually invented a can crusher for us by welding a metal plate onto the end of a metal rod, which made it much easier and faster to flatten our aluminum treasures and bag them for delivery. Once a few garbage bags were filled, he would drive them off, sell them to the recycling plant, and we would start collecting all over again. It wasn’t until years later that I realized he had been putting all of the money into savings accounts for us grandchildren.

He also helped me and my brothers secure our first paper route. While I can’t say that this was one of his best ideas for us, I do appreciate the attempt to help us earn money for baseball cards and toys, among other things. Of course, that came at a great expense. We would typically wake up before 6:00 in the morning – rain, snow, or otherwise – to walk behind our mom’s car, pull the newspapers from the trunk, and make sure that the nit-picking recipients received their paper exactly where they wanted it. But before they could be delivered, we had to bag them, and if it was a Sunday, we even had to insert all of the weekly coupons that were separately dropped off for us.

On Wednesdays, my brothers and I had to walk around the neighborhood and knock on doors to collect for the previous week’s deliveries. Despite the desire for wanting their papers delivered, many of the old folks were reluctant to pay – even if it was a cute seven year-old boy at the door. When it was all over, and after we had walked around to the 60+ houses on our route, we would be lucky to come away with a couple of dollars each week in profits. Needless to say, it didn’t last too long – and I can’t say for sure whether my mom was disappointed or delighted.

My parents divorced when I was very young and my brothers and I lived with our mother. She worked full-time at a local hospital, often putting in 60-hour weeks, including occasional late shifts. We frequently had to spend our evenings at our grandparents’ house while our mother worked later than expected – but since our houses were only one street apart, it was a convenient arrangement.

If the weather was bad enough, our grandfather was almost certain to show up and drive us to or from school, which was otherwise nearly a mile-long walk. He would roll up in his late-70s, red Mazda pickup truck with a white bed cover. One of us would hop in the cab and the other two would jump into the back. Off we would go, with the soft roar of the four cylinders and the skinny tailpipe, and the cloud of smoke exhaled out of the driver’s window.

My grandfather was a life-long smoker. We never really talked about it, but we knew that it wasn’t good. He would occasionally send me or my brothers to the gas station a couple of blocks over with a hand-written note and a dollar or two. We would hand the note to the clerk, he would put a pack of cigarettes into a small bag, and we would be on our way – straight back to grandpa’s workshop. A pat on the head later, and we were back to playing basketball in the driveway, shooting at the backboard and rim attached to the front of the garage, watching the puffs of smoke and listening to wrenches and other tools clanking from under a car hood.

When I had first learned about his lung cancer, I was around nine years old. I don’t remember exactly how or when it happened, but my grandfather had undergone a tracheostomy. He spent the rest of his life plugging the hole in his throat with his thumb when he wanted to speak or using an electro-larynx device that was conveniently dubbed “Mr. Microphone.” A piece of white cloth covered the stoma, which sort of made him look priestly as he wore his daily button-up shirts.

He was an excitable man when it came to topics like politics – something that had obviously worn off on me. After the tracheostomy, he would often become agitated and want to gripe about something, but Mr. Microphone would be in another room. He would try to plug his throat and get the words out with emphasis, but he would usually fall short of this task, becoming even more irritated about that than the actual misdeeds he wanted to criticize. On some occasions, Mr. Microphone’s batteries would die, which would lead to further frustration. This was usually compounded by our laughter – taking cues from our mother or any aunts and uncles that happened to be there.

After a couple of years had passed, my mother remarried and we were set to move seven hours away from our hometown. Being away from family, I was even less aware of my grandfather’s condition. Two years later, after another move, we found ourselves twice as far from home.

It was close to Easter during my first year in high school when we had heard the news: our grandfather wasn’t doing well. He had taken a bad turn and was under hospice care at home. My mother and step-father hopped on a flight while my brothers and I finished the last of our important tests and classes before our spring break. We left a couple of days early and my brothers drove for fourteen hours straight until we made it to our grandparents’ house around eleven o’clock that night.

When we arrived, my mother was there to greet us. She explained the situation to prepare us for what was inside. She encouraged us to go talk to him and to spend as much time with him as we needed.

She gave us a hug and we walked into the house. Nothing she had said was able to soften the blow of what I was about to see.

My grandfather was lying in a bed in the middle of the living room. He was barely recognizable. The six-foot tall and 170-pound man who was once proud, boisterous, helpful, and loving was now silent, emaciated, and helpless. His face was sunk in – his jaw slightly hanging open and tucked under his upper front teeth, which were now exposed. His eyes were widened and it appeared to drain what little energy he had just to faintly blink. He weighed less than 90 pounds, but looked even more like a skeleton.

It was a shock to see him like that. Despite everything that had happened previously, the worst thing I had ever seen was an occasional glimpse of the dark hole in his neck. I never understood how bad his health truly was. I had never experienced actually seeing someone in my family dying before – and at that point, I knew that I never wanted to see it again.

I walked into the doorway and instantly felt that I didn’t want to be there. I didn’t want to look at him. Everything seemed out of place. I felt extremely uncomfortable. I was in utter disbelief, perhaps even denial.

I loved my grandfather very much, but that couldn’t have been him. That wasn’t him!

It had been at least the previous summer since I had last seen him. Everything was normal then – or at least as normal as everything had always been. How quickly things can change. I was now receiving my first real lesson on the fragility of life…and I wasn’t ready for it.

I nervously watched each of my brothers sit beside my grandfather, hold his hand, and talk to him. They even kissed him on the forehead as they finished with whatever it was that they said to him. As they both moved away from the bed, it was now my turn.

I dreaded the moment. My mother nudged me but I tried to ignore her. “Go talk to him,” she whispered. “You may not get another chance.”

Given my grandfather’s condition, I knew this was likely true. Still, I couldn’t accept it. I really didn’t know what to do – what to say. It wasn’t like I was able to practice for this. It had never happened to me before.

She gave me another nudge. “Go talk to him, please,” she said in a more stern tone, accompanied by a look that appeared to me as growing anger.

At this point, I was on the verge of an emotional breakdown. Another push and I would surely burst into tears. I was lost and confused. I had no words, but I knew my mother was right. I had to go talk to him. I had to be there for him. I knew that he loved us all and was probably only alive right now because he was waiting to see us one last time.

I timidly walked over to the side of the bed. I noticed that my grandfather had seen me. His eyes slowly tracked me as I approached. I sat down in the chair, more uneasy than I had been while waiting in the doorway. Before I could think of what to do, I noticed his brittle hand slowly reaching for me.

“Oh, please, no,” I thought to myself, instantly feeling guilty for it. With what must have taken tremendous physical effort, he turned his head toward me and fumbled at my hand with his. I reluctantly took his hand and he clasped mine – apparently as tight as he could.

For the next hour, we remained like that. I sat in the chair, trying my best not to make eye contact. He laid in his bed, staring at me and never loosening his grip. For the duration of our contest, I was one wrong thought or one panicked move away from uncontrollably crying.

I thought of everything I wanted to say. I imagined telling my grandfather about how much I enjoyed our time together and valued the knowledge he bestowed on me. I thought about telling him that I was sorry for not taking a more active interest in auto mechanics, which he never tried to force on us. I remembered sitting next to him every time we ate a meal at my grandparents’ house – and all of the times that he stole food off of my plate, then laughed about it. I thought of the times that I was able to sit in the cab of his truck when my brothers weren’t around and we would take a ride to my aunt’s house, the hardware store, or to see one of his many friends. I recalled all of our walks to the barber shop at the end of the street where we received our routine trimming. I mostly wanted to thank him for being a positive role model for me and my brothers and for acting as a father to us when ours was almost completely absent. I really just wanted to say that he was a good man and that he will be missed, but that he will always be with me.

“Just tell him that you love him,” I pleaded with myself. “There’s nothing to fear. Nobody else cares if you say it. They’ve all said it too.”

But I was silent. I didn’t know how to express these thoughts and emotions, particularly to a dying man – and especially in front of other people.

Everything that I had wanted to say to him...was gone. Instead, I quietly said, “I’m going to go now, grandpa.” It took everything in my power to hold back the tears.

He just kept staring at me. One final look – perhaps him saying goodbye in the only way he could. After what felt like an eternity, he loosened his grip on my hand and I slowly pulled mine away. I stood up, walked upstairs, and I went to sleep.

The next day, my brothers and I drove out to our aunt’s house about fifteen minutes away. There was more room for us – she had about 5500 square feet in total – so we would be sleeping there for the week. We stopped by to see everyone at our grandparents’ house that evening and again the following afternoon. I didn’t sit with or speak to my grandfather again. That night – at around 2:00 in the morning – my aunt woke us up in tears.

My grandfather was gone.

The rest of the week was a blur. A lot of time was spent in the funeral home. I did my best to avoid the casket, dedicating most of my time in the basement that served as a small banquet room. I just wanted to be alone, but I was joined by a younger cousin. For the better part of two days, we stayed down there, each sneaking an occasional cookie or two from the food platters.

I never said my good-byes. I never expressed my love or my gratitude. I only hoped that my grandfather knew that I was in fact grateful for everything that he had done for us. I bottled everything up and I carried on with my life – and I’ve regretted every second of those missed opportunities that I had with him.

Later on in my young adult life, I made a promise to myself to never let this happen again. No matter the circumstances, it was a promise that I intended to keep.

Together Once Again

Twenty-two years after my grandfather had died, my grandmother was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Still separated by 1000 miles and having made my promise to myself, I was ready to go see her. I received a call from my mother.

“Hi, David. You should plan to come visit soon. They just admitted grandma into the hospital again. They think she might have pneumonia.”

The doctors had said that my grandmother had a good chance of living for several more months without treatment, which she declined after one visit and never really wanted anyway – on account of watching her husband go through it two decades prior. I was already prepared for this and I was ready to leave as soon as possible, if something should happen. The pneumonia was treatable and they had hoped to have her out of the hospital in a few days.

Nevertheless, I packed a suitcase and left the next morning. I had absolutely no intentions of repeating history. My wife stayed home, so I would be traveling alone. To break up my 14-hour drive, I visited other family members around the half-way point and stayed the night with them. I ate breakfast with them the next morning and then I was on my way.

It was a nice drive. The weather was perfect. I had plenty of time to myself to try to go over everything that I could possibly want to tell my grandmother. I was excited to see her – it had been a couple of years, unfortunately – and I was happy to be able to fulfill my promise. I had planned to visit around Christmas, but I was more than thrilled to be able to make two trips to see my family in the same year, even if the circumstances weren’t the best. Everything was going smoothly and my hopes were high.

About two hours from my destination, I began receiving texts from family members.

How far away are you?

When do you think you’ll get here?

Grandma just ate a little bit of ice cream.

How much longer do you think you’ll be?

Grandma is sleeping now. They increased her morphine again.

Wait, what? Morphine? Why is she on morphine?

Do you think you’ll be here in the next hour or so?

Grandma’s breathing is very shallow.

Hey – just wondering what time you’ll get here.

Grandma just said good-bye to everyone.

What the…? Good-bye? What the hell is going on? My mind started racing. I received a phone call from my brother.

“Hey, where are you?”

“I’m about 30 minutes out. Just stopped for some gas. What’s going on? Why is mom sending these texts about morphine and grandma saying good-bye? Should I be flooring it right now?”

“Well, grandma’s been having a hard time breathing. They have her on a morphine drip. It’s been too painful for her to eat anything.”

“How bad is she?”

“I don’t know. When we left, she seemed to be doing OK. We’re about to head back to the hospital now. We had to get the kids some food and just wanted to relax for a couple of hours. The aunts were driving everyone crazy.”

“Yeah, I bet. Alright. We’ll probably get to the hospital around the same time. I’ll call you when I’m close.”

About 30 minutes later, I pulled into the hospital’s parking lot. My brothers had just arrived and were waiting at the entrance. The three of us walked in together, took the elevator to the sixth floor, and headed towards the room. I breathed a sigh of relief. I made it. Now, I just had to gather enough courage to say everything that I had wanted to say to my grandmother – and to my grandfather before her.

We turned a corner and I could see all three of my aunts and my uncle at the end of the hall. They were standing across from one another but didn’t appear to be talking. As we got a little closer, I saw that all four were crying. My uncle looked over to us as we approached. He said nothing.

He just shook his head.

The smiles and light banter between my brothers and I abruptly ended. One of my aunts came over and hugged each one of us, sobbing.

“I’m so sorry, David,” she said to me.

“No – this can’t be right,” I thought. “What’s really happening here?”

I walked into the room and saw my mother, her cousin, and her uncle – my grandmother’s brother. And there she was, resting on the bed. The grandmother that I had loved, the sweetest lady that I had ever known, the perennial matriarch that was the glue of the entire extended family. Never an unkind word about anyone, always putting everyone’s needs and desires before hers, volunteering much of her time and energy to her church and cooking for their various public events. She was loved, respected, and saintly – not a fault could be found with her among her family and peers.

The only thing I wanted to do was to tell her all of these things and how much she meant to me, despite the distance between us over the last two decades. But now she, too, was gone.

I stood there in disbelief. This just wasn’t possible. I made sure that I would be able to say what I wanted to say. I planned for this. I didn’t hesitate or procrastinate. I got in my car and I drove, knowing that I had plenty of time. She had several more months to live, after all. That’s what the doctors had said.

One of my brothers had asked my mother, “How long ago?”

“About ten minutes.”

Ten minutes?! I missed her by TEN MINUTES?! I fell against the wall and hung my head. I starting thinking – if I had woken earlier that morning, I would have made it in time. If I had skipped breakfast or not stopped to eat my sandwich, I would have made it in time. If I had decided to fly instead, I would have made it in time. There were so many things that I could have done differently that would have put me in that hospital room while she was still alive.

My mom came over and hugged me. “You tried,” she said. “I told her that you guys loved her. She said she knew it.”

I know that my grandmother knew we loved her, but that wasn’t the point. It didn’t relieve me in any way. I wanted to say those things to her myself – if not for her, then for my own sanity. For over twenty years, I regretted not saying it to my grandfather; not being able to tell him what he meant to me and saying good-bye to him. For over twenty years, I promised to not allow that to happen again when the time came.

I failed to keep that promise.

I walked out of the room, past the aunts, uncles, and brothers, and found a seat down the hall. A few minutes later, my mother approached and asked, “Do you want to go say good-bye to grandma?”

Say good-bye? She’s gone! I already missed that chance. It was over. There was nothing that I could do to change it. If I had arrived at least eleven minutes earlier, I may have had that opportunity – but not now.

I responded curtly, “No.” And that was it.

We left the hospital about twenty minutes later. I sent a message to my wife:

Wasn’t fast enough.

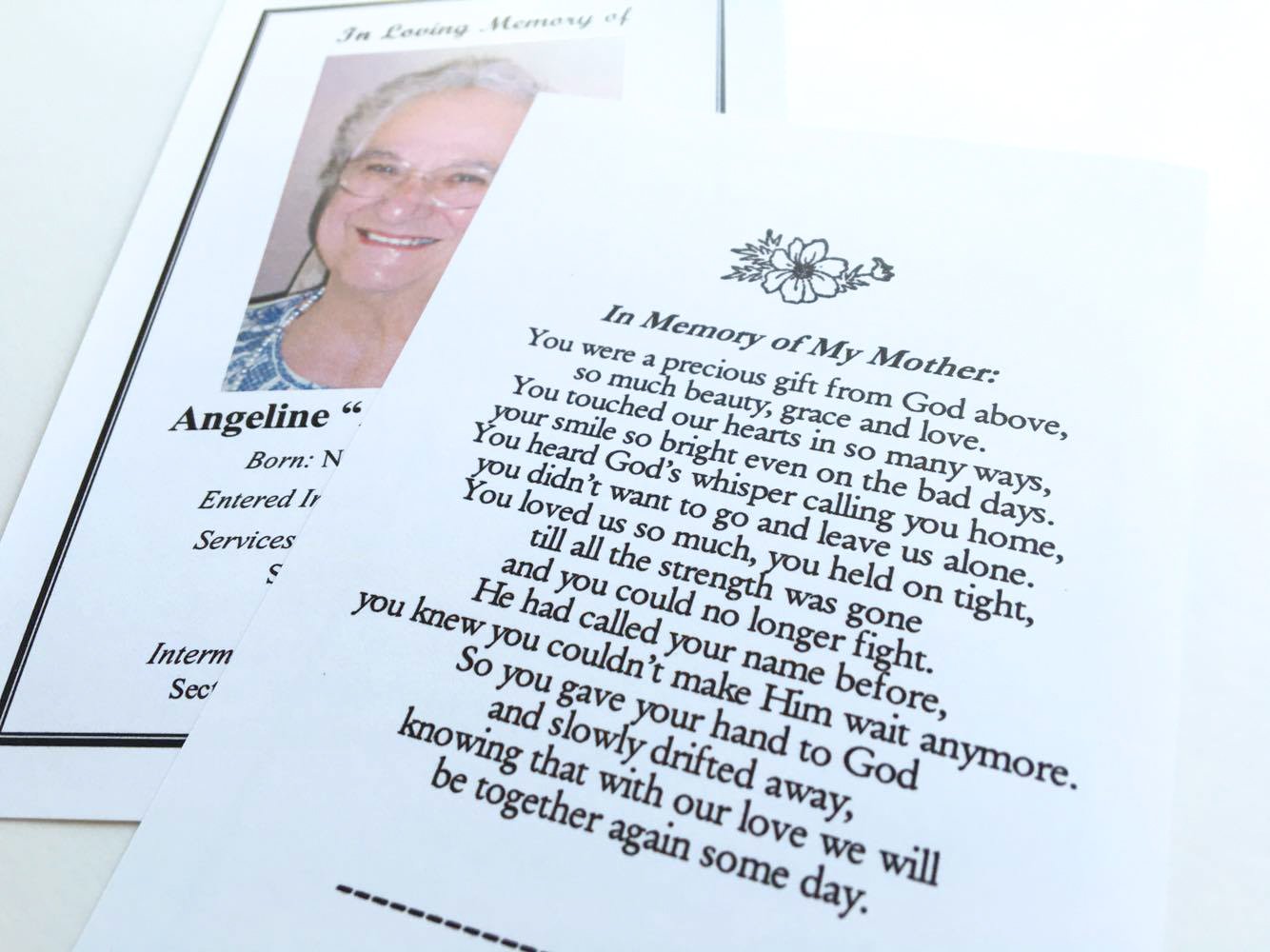

I was quite emotionless the rest of the week. I was volunteered as a pallbearer by my grandmother – who had made all of the funeral arrangements herself after learning about her cancer. The eulogy – delivered by her niece – was beautiful and really captured her essence as the matriarch of our family and as a phenomenal human being. I performed my duties with my brothers and cousins and we laid her casket next to the plot of her late husband – our grandfather.

Everyone began to clear out after a few closing words by the funeral director. I stayed behind. I told my wife that I would meet her at the car in a minute. She gave me a hug and slowly walked away.

I stood there, staring at the coffin. I’m not really a spiritual man and I don’t believe there’s anything waiting for us on the other side of death, but I apologized to my grandparents. If there is more to death than eternal nothingness, I hoped that they could forgive me, because I knew that I wouldn’t be able to forgive myself.

I put my hand on the coffin and said, “I’m sorry, Grandma. I love you.” And then I turned and walked away.

Both grandparents were now gone. Both left this world without hearing from me how I truly felt about them. In both cases, it was entirely my fault that the words were never spoken. This is my own emotional weight to carry now, and it is heavy indeed.

A Few Closing Thoughts

It’s not easy for me to talk about this and it took me several sessions to get through it. My grandparents truly were amazing individuals and an extraordinary couple. It hurt to see my grandmother alone for as long as she was after my grandfather died. I have a tremendously deep regret for not expressing my love more openly to both of them.

If you take anything away from my story, let it be this:

If you love someone, then tell them. Don’t worry about what anyone else thinks. Their thoughts just don’t matter. You never know when your time is up, so don’t wait for the “perfect moment” or wait until that person’s deathbed. It’s never too early to express your love.

Don’t be afraid to show your emotions – especially to those you love – but don’t feel guilty if you can’t. Trust me – it will break you down over time. Everyone doesn’t express themselves in the same manner, so don’t beat yourself up for “doing it wrong.” Just make sure that you…

Live your life as purely and as honestly as you possibly can. Say the things that you want to say. Do the things that you want to do. You don’t need to hide who you are or how you feel. You get one shot at life. Surround yourself with people that make you happy and that enrich it – and let them know what it means to you that they are there for you.

If you’ve had a similar experience to mine, just know that you’re not alone. We don’t do everything perfectly. We live and we learn – and hopefully don’t repeat the times in our lives that we dislike or have regretted. I hope that my experiences here will help someone who may be having trouble with these emotions in their own life. Losing someone you love is never easy. Don’t compound it with regret.