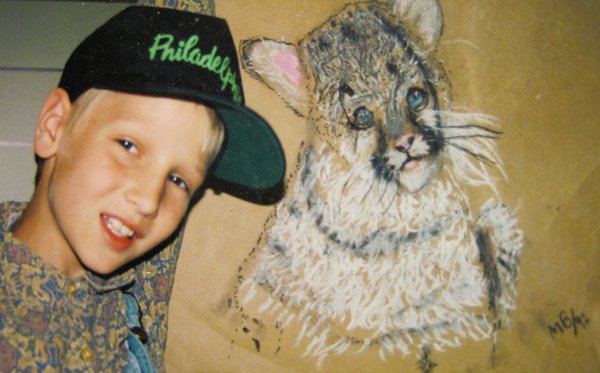

Having grown up in a creatively-inclined family, the arts have always been part of my life.

I began learning how to transform colors into pictures a young age.

By 16, I was living off ramen noodles in a one room apartment crammed full of mediocre oil paintings and doing education at a weird little art school. At 18, this school was shut down by the law for being corrupt. By the time the state approved my graduation a few months later, I had already moved to Chicago and was learning to peddle my art on the street. From there, I traveled around and became interested in the intentional community movement. By 24, I was living with a crew of artsy idealists determined to form an urban ecovillage. I worked all sorts of jobs to make ends meet, planned to use financial aid that would become available when I turned 25 to pay for college, and painted weird abstracts like this:

Then there was an accident.

I fell through a hole in a poorly-maintained balcony and landed on my back three stories below. In that moment, everything changed. Even after all the torn muscles had mended themselves and I was again able to walk without frequently pausing to rest, my body no longer fit together quite right, was sore all the time, and did not let me do many of the things that I expected of it. Making decent art became impossible, because some subtle part of how my brain and my hands communicated with each other no longer worked right.

Then the headaches started.

They were like migraines but much, much worse. Each attack lasted between one and three hours, and there were a hundred of these or more every month to contend with. It was like living in a horror movie. These turned out to be what are called cluster headaches, and they are seriously bad news.

Cluster headache is one of the most painful conditions known to medical science. Its symptoms amount to torture. While it is a stretch for most people to imagine the unpleasantness that accompanies the purely physical sensations of being tortured, this is something that most people can sort-of imagine if they try. Many can even imagine the physical toll it would take on a body to experience one or more discrete torture sessions per day for an extended length of time. The might not enjoy imagining this, but are more or less able to do it. Sometimes, they can even sympathize. But the psychosocial impacts of an incurable, cripplingly painful and poorly understood condition like cluster headache are another matter.

Imagine that a small device has been implanted deep beneath your skull without your knowledge. When a button is pushed at some unknown remote location, the implanted device sends a signal to your brain - instructing blood vessels deep beneath your skull to crush one half of your head from the inside out. Sometimes, the remote control for this device is in the hands of an evil scientist, who likes to press the button every time you drift off to sleep, or everyday at - for instance - 8pm, or an hour after you wake up on days where atmospheric humidity exceeds 55%, or every six hours around the clock. Other times, the remote control falls into the hands of this scientist's small child, who just presses the button for fun - repetitively - at random intervals. Now and again, the remote control gets lost, perhaps in this terrible fellow's couch cushions or something, and weeks or months pass by where the button does not get pressed. But then the remote turns up again, eventually, and your horror of unknown origin resumes.

Imagine that this goes on for years. The doctors that you go to give you drugs that cost a fortune, sometimes make you sick, and do not actually work. You learn a hundred different ways to lessen the impact of such wretchedness on your life - but there is only so much that can be done. Often, the entirety of your week is spent alternating between writhing in incomprehensible pain and succumbing to the sheer exhaustion that comes in the aftermath of the acute torment. All the while, most people remain unaware that the medical condition which plagues you exists; even close friends and family members sometimes act as if you are making it up or exaggerating the havoc it wreaks. With the passage of years, the people in your life come to accept its reality - but by that time they tend to be tired of hearing about it, and begin unconsciously avoiding you or treating your difficulties as inconsequential.

Imagine that the shallow end of this abyss involves being treated like a guinea pig by unhelpful practitioners of industrial medicine, being rendered a pauper by prolonged inabilities to work or keep any kind of regular schedule, being categorized as unfit to receive assistance by dim-witted bureaucrats administering social services, and being unable to participate in many of the activities that constitute social life. Over time, as these abyssal waters become deeper, more subtle and longer-term intricacies of the nightmare are revealed. The coercive inhumanity endemic to our society is laid bare. The insular banality of increasingly affection-starved years intermingles with the slow disappearance of choices as degrees of freedom are shaved from everyday life by a slow accrual of social exclusions. The future is transformed into a place that no sane person would willingly enter, such that hope becomes indistinguishable from a pragmatic dishonesty that allows life to continue on regardless.

A few years into this, something had to change.

I had put together a life that was mostly okay, but had no long term prospects. My life was good, but it was not good enough, and there was nothing I could do to make it good enough. So, perhaps more to kill time than for any other reason, I decided to teach myself how to paint again as if I had never done this before.

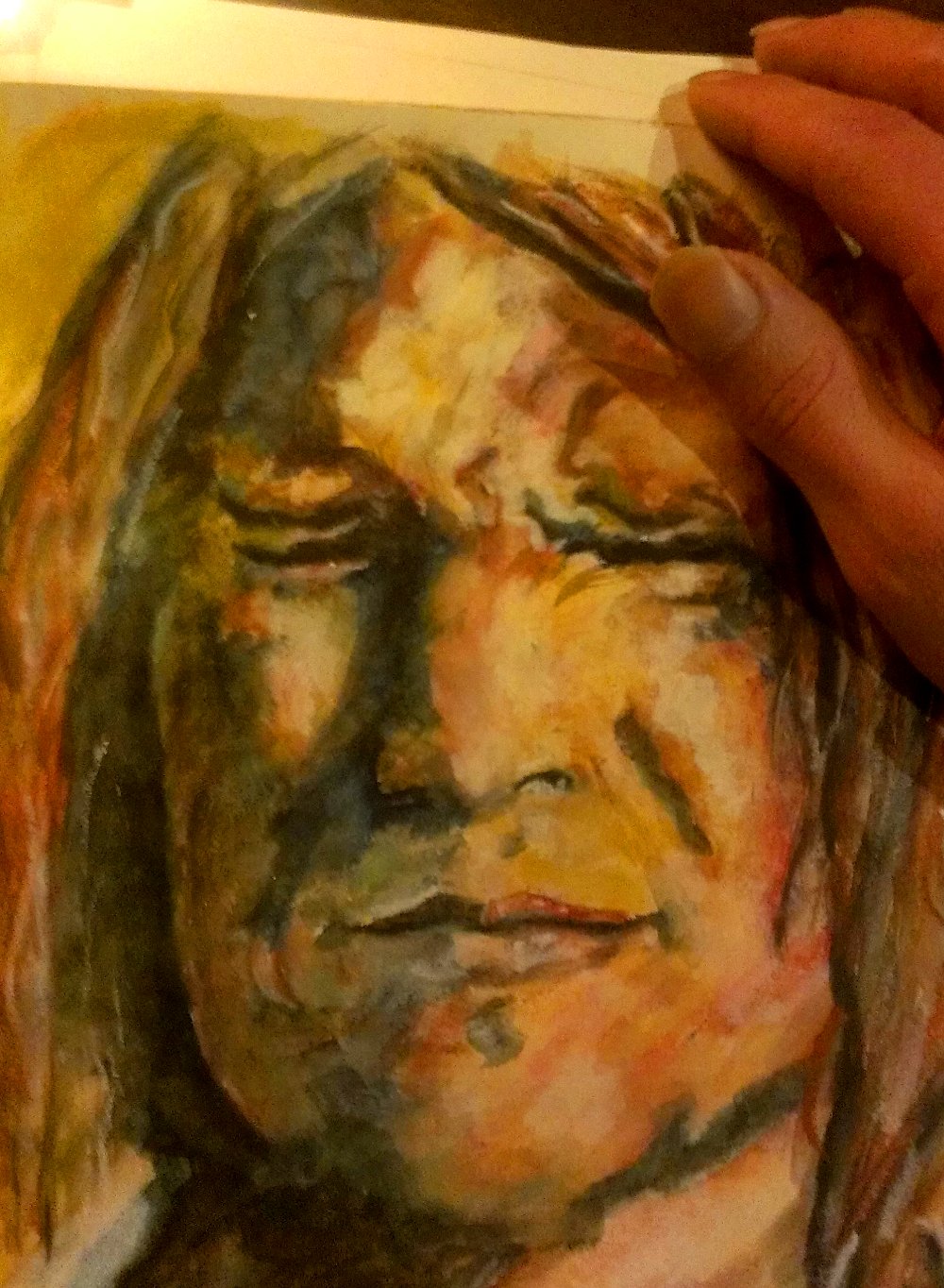

I started re-learning how to paint.

Although this was frustrating at first, it was an excellent distraction from the fact of my life circumstances, and I made steady progress. Within a year, I got a handle on the kinds of paintings I wanted to make, and really just had fun with the whole thing.

People at the coffee shop made good subjects for impressionistic portraits.

After doing live oil painting at a few events, hanging a few local shows, and generally bumming around being a stereotypical starving artist, it did not matter as much that my long term prospects were nil for reasons I had no control over. I found that just being a little less miserable made it easier to get along with people, and my relationships with those around me started to improve.

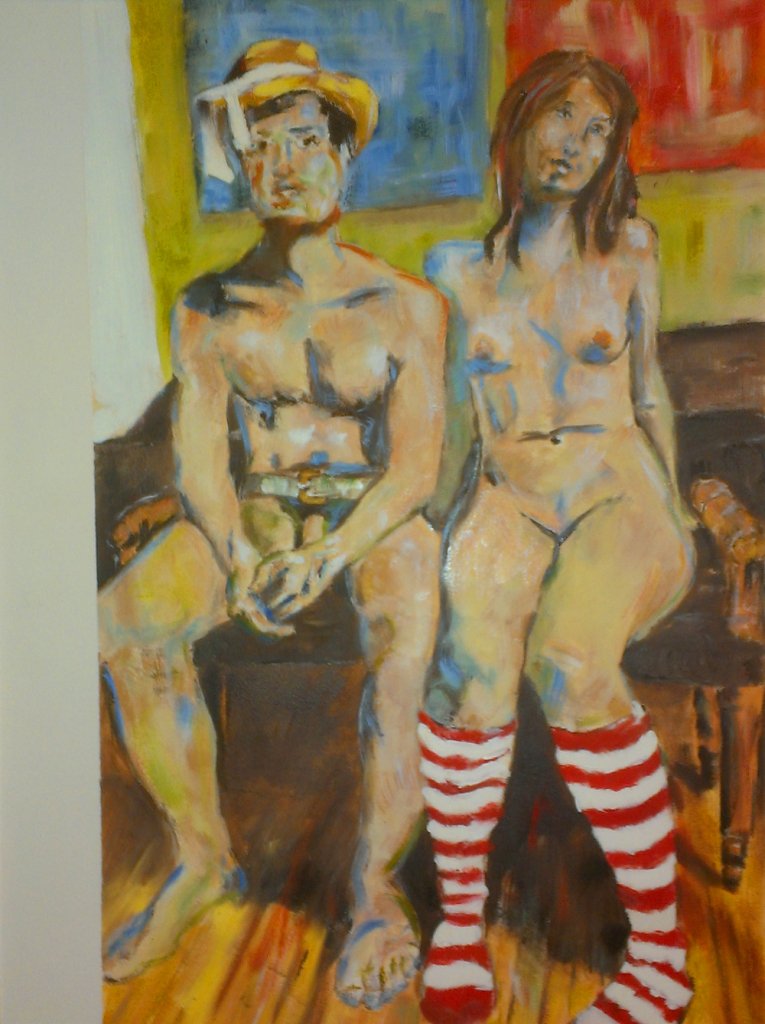

Since the human form can be used to say just about anything, I mostly painted figures.

Sometimes I bought images from an art models website, other times I worked from live models in my studio. So long as there was a decent reference photo or two to go along with the sketches that came out of even brief live modeling sessions, I found I could take as much time as I wanted to develop an idea into a finished work of art. A complete full-sized painting might have a dozen drawings and one or more painted studies behind it.

As my style evolved into its own thing, the work became at once more simple and more complex.

By painting big, using limited palettes, and doing tricky stuff to create a wide variety of textures, I eventually found myself making art that I was happy with.

Doing all of this created the psychological space to begin seeing the world in totally different light than merely living with chronic pain had allowed me to.

It challenged my sense of perspective, and gave me the opportunity to begin exploring exactly how people's viewpoints assemble what world they see.

Now, obviously I will never be a great artist or anything. But even when I can not do anything else, I can still paint.

And, though I have no intention of filling my steemit blog with attempts to market art that really has to be seen in person to be properly experienced, the role that painting has played in making my everyday life manageable seems like the kind of thing that someone here might find value in.