I met him one gloomy October evening. It was drizzling. The last leaves were falling from the elms along the bank. There wasn't a soul in sight. Abandoned rowboats were becoming rainsoaked at the pier. A river steamer bellowed hoarsely. Then a bird in the rushes whistled long and mournfully. I listened to it, trying to guess what kind of a bird it was, and then noticed him. He was standing under an elm, cap in hand, dressed in an olive-drab raincoat with shoulder straps. He, too, was listening.

When I returned about twenty minutes later, climbing the path that ran along the bank of the Don, I saw him still standing bareheaded under the elm, his raincoat now dark from the rain.

I couldn't help saying: "Have you ever been here before?"

"Not in forty years."

We were silent for a while, watching the water rippling around the nearest buoy.

"I got here from France ten days ago. I was born in Vyoshenskaya, though. I remember when I untied a boat right over there. That was forty years ago." His voice wavered. Suddenly he became embarrassed, smoothed his crumpled cap and put it on hastily.

The door squeaked continuously as men and women kept entering the large crowded parlor. After all, the man had been away for nearly a lifetime.

"Mustn't be too good there if you've come back," a bearded old Cossack was saying.

"There's the good and the bad."

"Did you come by ship or by plane, Pyotr?" the old man asked.

Pyotr's mother sat at the table. She hardly spoke. She just sat there, gazing at her son. Her gnarled, workweary hands were folded in her lap. He had been gone for forty years, and now she was trying to reconcile the thirteen-year-old boy last seen here on a June morning forty years before with the graying, soft-spoken, gentle man, Pyotr Moiseyev, her son. He was telling his fellow-villagers his story.

The Don Cossacks smoked and listened in rapt silence. The lamp was as a yellow moon floating under the ceiling, while the walls seemed to be melting away in the smoky haze. I imagined the thirteen-year-old boy and his chum untying a boat, then catching a pair of horses on the other side and galloping towards the railroad station. From there they hopped a crowded freight car filled with the smell of horse manure and the sounds of the Cossacks' filthy brawling. There was a terrible commotion at the pier, followed by a rough crossing and Turkey.

All this happened during a time of unrest on the Don. The Whiteguard Cossacks, fleeing from the revolution, first lured the two boys off with the promise of adventure and then frightened them with threats of being persecuted if they returned to Soviet Russia. In the end, the Cossacks abandoned the children in an alien land, for it was each man for himself if they didn't want to starve to death.

One of the women in the room sighed and wiped away a tear. His mother did not weep. She just sat there, gazing at her son. She probably had no tears left.

"We were willing to do any kind of work for a meal. We swept the streets, cleaned stables, ran errands, loaded crates of vegetables in a port in Bulgaria, pushed cars of ore and worked in a butcher shop."

"If you want to survive, keep closer to the workers," a kindly old Bulgarian had said to two boys left adrift in the world.

Then Pyotr's friend became sick and died. Later, Pyotr Moiseyev became a steelworker. He stoked the furnaces for thirty long years, sharing life's joys and sorrows with his French comrades.

In the beginning, after his years of wandering, the quiet town in the southeast of France where the metallurgical plant was located seemed like a haven. The flower-decked meadows came right up to the factory yard, with orange groves farther down the slope and snowcapped mountains in the distance. Even the name of the town, Ugine, sounded festive. Tourists from all over flocked here to enjoy the beautiful scenery.

"Shall we settle here?" Pyotr asked the Russian girl named Masha, whom the confusion and chaos of life had brought to this beautiful spot.

So he smelted steel while she made hats for the local ladies. In the evenings they would set out for the mountains, returning always with an armful of flowers.

"The two Russians seem very happy together," the women of the town observed.

As Pyotr was arranging the flowers after their walk one evening he found a stalk of plain-looking grass among the bright blossoms. When he rubbed it between his fingers the room became filled with a tangy, fragrant smell. He was silent and thoughtful for the rest of the evening and then rubbed the grass between his fingers again before going to bed.

"This is oregano. We called it dushitsa back home," he said to his wife.

When they wandered through the meadows after that, Pyotr would always look for dushitsa, a rare grass in these parts. No longer would they bring home bouquets of wild flowers. Instead, they would have a small bunch of light-green, fragrant dushitsa. After they bought a shortwave radio the light burned late into the night in the house where the Russians lived. Pyotr would turn the knob until he heard a voice from afar saying: "This is Moscow..." They would travel over a hundred kilometers to the nearest big city if a Soviet film were playing there.

One day Pyotr brought home a dogeared book. It was And Quiet Flows the Don. They read it aloud together.

"So this is what was happening on our Quiet Don," Pyotr said. "You know, Masha, I used to go to school with the author. They say Sholokhov still lives in Vyoshenskaya. I wonder if any of my family are living."

A month later the postman brought him the answer, a gray envelope postmarked "Vyoshenskaya".

"It's from my mother," Pyotr said softly as he gazed at the sheet of paper torn from a notebook.

It was far past midnight when the bottle of vodka ended and the visitors filed out, saying they'd come back the following day to hear the end of the story.

Pyotr Moiseyev has the large hands of a workingman. He sat his mother and wife down beside him and continued in an unhurried voice.

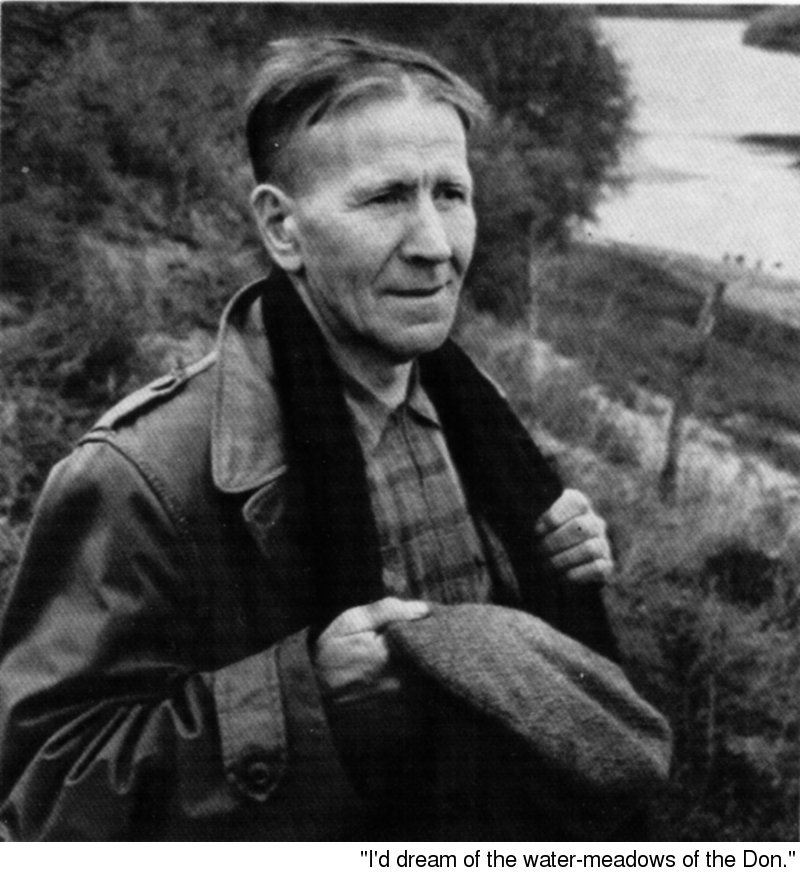

"The last years were spent with only one thought in mind: we're going home! We sent in applications and wrote inquiries. We knew it would not be easy, for so much had happened in forty years' time, so many people had been scattered all over the world. Still, we could not give up our dream. We always looked ahead with hope. I can't even tell you what that feeling is like. I'd dream of the water-meadows of the Don. Masha and I spent hours looking at clouds that were drifting to the east. It's the truth, believe me. We were like people possessed, gazing up at the mountains and the clouds floating past them. Then the first sputnik was launched in the Soviet Union. I wept from joy. Those were our countrymen who'd done it. Masha and I were very excited the day we were finally summoned to the prefect's office."

The conversation there was short and to the point. Four officials from Paris ushered Pyotr Moiseyev into a large room. The four men in dark suits were very polite.

"So you're going to Russia, monsieur?" the youngest asked, peering at him intently.

"Yes, monsieur."

"Have you thought it over carefully? After all, you're practically a Frenchman. You speak like one . . ."

"No, monsieur, I'm Russian," Pyotr replied in Russian.

"Why are you so eager to go there? Do you miss being sent to Siberia? Where you'll have to work at some construction project? I'm sure you know what I mean." The man opened the window. The familiar mountains loomed large. "Look. You won't find anything like this there. All those people know is work, work, work."

"I'm not afraid of work, monsieur. Look at my hands. They're not used to living without work. I'll be happy if there's a lot of work." And he added, "Where were you born, monsieur? How old are you? Is your mother living? Only twenty-three? I don't think you'll understand me if I tell you I've never wept. I was beaten at a Turkish bazaar for having stolen a flatcake, but I didn't cry. I didn't weep when I buried my best friend on the way to France. Only the gas from the blast furnaces could make my eyes tear. But now, and I'm not ashamed to say this, I weep when I hear a song. A song from my own country. Do you understand, monsieur?"

"Then it's definite?"

"Yes."

The four men stepped aside to let the Russian pass. Pyotr stopped in the corridor. His head was spinning. The sun coming through the open door blinded him. The four officials in dark suits walked by him. The last, a middle-aged man, stopped for a second and pressed his hand.