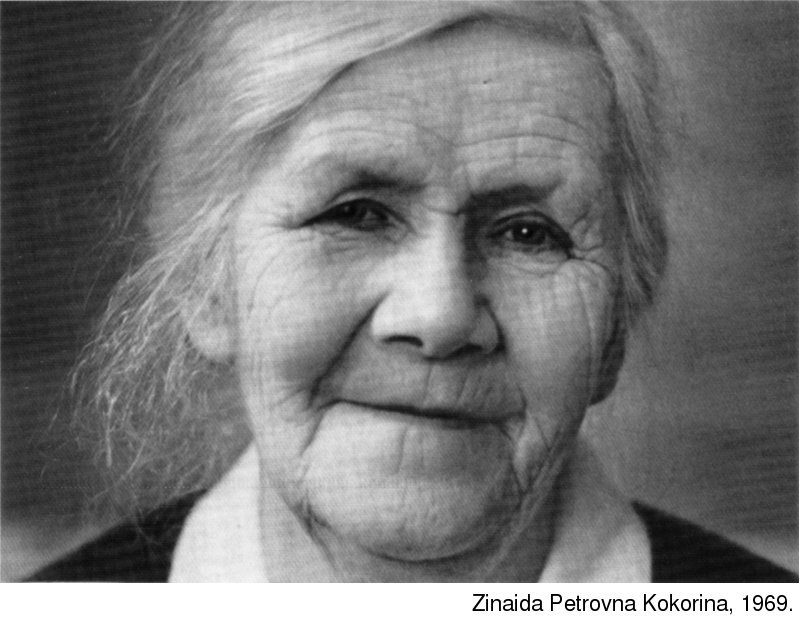

Look at this woman's face closely. If you try to guess what she used to be you will probably say she was a schoolteacher. And that is correct. In some unfathomable way a school leaves its mark on the faces of those who serve it. Zinai-da Petrovna Kokorina was a schoolteacher and the principal of a school for nearly thirty years. However, both former pupils and recent graduates from the village school in Cholpon-Ata near Lake Issyk Kul in Kirghizia will be surprised to read this and learn that their gray-haired, kindly history teacher was a pilot. Not simply a pilot, but the first Soviet woman to fly.

This was all very long ago, if we are to judge by the progress aviation has made. It was at a time the country did not have its own planes and used French Farmans, Nieuports and Morane-parasols. Looking backward from Tupolev's latest TU-144, a truly fantastic plane, this seems like another era. Actually, though, it is recent history, if a person who flew a Nieuport can now fly, as a passenger to be sure, in the new superjet.

Zinaida Petrovna is seventy years old. She never saw a plane in her childhood, since none crossed the sky of Russia in those days. Besides, the family of the deeply-religious Urals prospector lived in a basement. All the children could see through their window were the feet of passers-by. They even invented a game, the object of which was to guess who a person was by his feet.

Her father never found a gold vein, and so the family was very poor. "We bought our bread from beggars. It was cheaper that way. I went to school in the winter, but worked at the local match factory in summer, pasting labels on the boxes. When I was ten I taught our neighbor, who owned a bakery, how to read and write and gave my mother the five rubles she paid me."

Such was her childhood in Perm. It would not be hard to discover the first indications of the perseverance that determined her character. Zinaida Kokorina was recommended for admittance to a secondary school, as she was a very bright child. It took much effort and hard work to graduate with a gold medal, while supporting herself by tutoring the daughters of the local merchants. In 1916 she decided to go to Petrograd and enter the University.

Let us imagine the five years she spent there as a student. The beginning of her adult life coincided with the Revolution, and so she found herself caught up in the whirlwind of flaming passions.

"This was a time of great expectations and great dreams. I don't think people had ever dared to dream so boldly before." In 1921, Zinaida Kokorina received her degree in teaching. She set out for Kiev, not knowing what lay ahead.

"A plane was flying over Kiev."

I listened to what she was saying and tried to imagine the scene: a plane was flying over Kiev. Men, women, boys, cabbies, soldiers, vendors and clerks stopped dead in the street. People opened their windows and doors and looked skyward. There was a plane in the sky. Although this was not the first time it was passing overhead, everything came to a standstill. Horses were shaking their heads up and down anxiously at the loud buzzing noise coming from above. A lightweight yellowish-gray aeroplane was inching along, according to modern standards, and streaking across the sky, according to ail the eyewitnesses. It soon passed from view and all was still again. The streets came back to life. Zinaida could not fall asleep that night. "I wondered whether this bird-man was like an ordinary person, or whether he was of a special brand of people. I was told that flying was only for men. I decided I wanted to see how men got to be aviators and began packing my bag. Bring me my suitcase, Dima," she said.

Her twelve-year-old grandson, who had been listening to our conversation, ran off. He returned with an ancient, battered suitcase.

"This is all that's left. I don't know how it survived. Here's my picture."

In the spring of 1921 a new librarian arrived at the flying school in Kacha. Her arrival did not make a stir, for who could have ever guessed what the tall and pretty young girl had in mind?

Kacha is a large, flat, dry area in the Crimea, a natural flying field. The first airplanes did not need concrete runways. A plane could land anywhere in Kacha, where the ground was covered with poppies in spring and with dry yellow grass in summer.

Three hundred men were learning to fly at the Kacha school. They were Russians, Latvians, Estonians, Italians, Hindus and Bulgarians. "I still remember many of their names. Angel Stoilov was a powerful Bulgarian. A live-wire Italian named Gibelli later became one of the heroes of Republican Spain. Kerim, from India, was a quiet, meditative man who always got down on his knees and prayed before climbing into the cockpit. These were all former proletarians, blacksmiths, plumbers and bookbinders who dreamed of flying. We all expected the world revolution to begin in the near future and knew that there would be battles ahead and that aviators would be needed."

Zinaida Petrovna has never forgotten Albert Poel. He was an Estonian and a former mechanic who was a flying instructor at Kacha. Poel was nicknamed Ace, as were all the other instructors. There was not a trace of irony in this nickname, for anyone who could fly well was a hero to the others, no matter that they could fly a bit themselves. The tall, silent Estonian soon became a regular at the library.

Albert and Zinaida fell in love that spring. Who can say what the measure of love is? Yet, if at seventy a person speaks of another with a catch in his throat, does this not indicate the deepest love?

"He was the first person I told I wanted to fly. And he understood me. One morning we headed towards his plane. I remember every minute of it. The mechanics exchanged surprised looks, because women hardly ever came out to the planes. We spun the propeller by hand. Then the red poppies whizzed by under the wings. I've always remembered everything that followed as the happiest moments of my life. We were in the air for about twenty minutes." Not long after, the pilots of Kacha were preparing to attend a wedding. The bride and groom, Zinaida and Albert, were to go to the registry office in Sevastopol on a Saturday. That Thursday Poel was unable to pull the old Nieuport out of a spin and crashed as his bride-to-be stood watching.

"He was buried in Sevastopol, with two crossed propellers for a tombstone. That's how all flyers were buried in those days. His comrades spoke at the graveside. Someone supported me. I felt I had turned to stone. All I could do was numbly try to count the other crossed propellers at the cemetery. The wine we had set aside for the wedding was served at the funeral repast."

Zinaida Petrovna fell silent. We both gazed out of the window. A sparrow hopped about on the roof of a wooden house nearby. It must have spent the previous chilly night in a chimney. Now the sooty, ruffled bird was coming to life in the sun, leaving a stitched line of tracks in the clean snow.

"Then what?"

"Then I went to the head of the school and the secretary of our Party cell and tried to explain the situation. They really couldn't refuse me. Three days later I was on my way to Yegoryevsk, near Moscow. That's where future aviators studied the theory of flying."

There were four girls enrolled at the school in Yegoryevsk. However, when a high-ranking commander from Moscow came to inspect the school he dismissed them all. He said the same thing Zinaida had heard so many times before, but he said it more rudely: "This is no place for dames." The People's Commissar in Moscow was very understanding, but he, too, refused, saying, "There are so many other professions you can choose from. But flying . . . You can't honestly say it's an easy job, can you?"

Mikhail Kalinin was now the only person who could help Yevdokimova and Kokorina, the two most persistent girls. He was the President of the Soviet Union. The girls went to see him. He did not try to talk them out of it, but listened attentively, worrying the tip of his famous beard. He finally asked: "Will you stand your ground?" Kalinin walked around his desk, shook their hands and added, "It's always hardest to be the first in anything new. Don't back down now."

"After completing the course in Yegoryevsk I set out for Kacha and the little old planes there. Our train stopped near Kursk, where the rails were covered by snowdrifts. The passengers got out to clean the tracks and gather wood for the locomotive. There was another stop near Kharkov, though the tracks were clear. The train whistle blew uninterruptedly for five minutes. Men stood in the bitter cold with their heads uncovered. The engineer wept openly. At that moment Lenin was being interred in Moscow."

Time marched on. Now Zinaida had a right to climb into a plane. Not to fly as yet, but simply to sit in the cockpit, touch the wings and spin the propeller for those who were going up. The planes were old and run-down. Not a day went by without some breakage. A pilot of today would have been stunned had he looked inside the cockpit of a Nieuport or an Avro: there was not a single instrument on the panel. Not one! "We checked the motor by its sound and the altitude by looking down. Actually, we didn't fly very high or very far in those days."

Each flight was a great occasion, ten or fifteen minutes of sheer delight. The rest was routine. Reveille before sunup and taps late in the evening. The students taxied around the field and dismantled the motors, which were constantly breaking down. They'd run for forty hours and then have to be changed. There were three motors to a plane. One was in the plane, one was at the ready in the hangar and the third was being repaired. "This was when I really discovered what they meant when they said it wasn't a woman's job. I not only had to keep up with the men, I had to be better, because I would never have been able to make them accept me if I was simply average."

Kokorina was first in everything. She was elected head of her group. She was the first to master the elements of flying, and when the time came for the students' first solo flight, her name was first on the list.

She soloed on May 3, 1924. There was nothing spectacular about the flight. The Avro took off, circled the field and landed at a specified point. It was a mundane event in the life of the school: another student had begun flying successfully. Looking back, we can say that in asserting one's rights a young woman had added another pebble to the pyramid of human values.

"I was in seventh heaven that day. We all wore the same flying clothes, but the bouquet of wild flowers I was handed as I climbed out of the cockpit singled me out."

Zinaida's third flight was a difficult one, for the Avro's hood was ripped off and landed on the wing. The plane began to fall, but she still managed to land it safely. When they later went over the details of the flight, a man, everyone respected greatly, said: "Kokorina will be a good flyer."

Indeed, she was to become an excellent pilot. Soviet aviation was then in the stage of inception. As before, every plane was purchased abroad. The names were new, but they were still foreign to the Russian ear: De Haviland, Martin-side and Fokker. The designers of Soviet IL's and YAK's were still at school. While at a glider contest at Koktebel in the Crimea, Zinaida Kokorina got to know two young men named llyushin and Yakovlev. They were completely unknown at the time. "Yakovlev could not have been more than eighteen. He saw my insignia and gaped. 'Are you really a pilot?' he asked."

However, routine flying no longer interested her. Zinaida Kokorina decided to become a fighter pilot and began a course of special training at the Higher Military School, where the enrollment was two dozen men and one woman.

Kokorina's marks in flying and target shooting were the highest in the entire graduating class. She was asked to stay on at the school as an instructor. Her old friends from Kacha came to see her. "Someone tugged at my sleeve and said, 'Zina, enroll me in your group.'"

"After graduating I served with the Borisoglebsky Air Regiment. From there I went on to Osoviakhim."

Today's youth has to open a reference book to find the meaning of the word.

In the 1930s Osoviakhim stood for a lot. A mighty, well-equipped army was being formed, and each person helped the Army in every way he could.

"Men who are famous today worked with us then. There were Ilyushin and Yakovlev, whom I already mentioned, as well as the rocket specialists Tsander and Sergei Korolyov. At the time I was deputy head of the Central Council's Air Department."

Flying clubs and schools were being organised, nearly every town built its own parachute jump, pilots were being trained by the thousand instead of by the dozen, and all of them were flying Soviet-made planes. Zinaida Kokorina headed a great project. She still has an autographed photograph the German airplane designer Fokker gave "the unusual Russian woman" during a business trip to the USSR. Any flyer would have been proud to be the object of the inscription's praise..

Inspector Kokorina flew to the various air clubs as a pilot, not as a passenger. Girls all over the country saw her. Polina Osipenko, the famous flyer, reminisced: "I was working on a chicken farm then. One day a plane landed outside our village. A woman climbed out of the cockpit. I can't tell you how excited I was to learn that women could also fly!"

The first swallow, no matter how early it appears, is always a herald of spring. By the late 1930s hundreds of girls had earned their wings. The non-stop flight of Polina Osipenko, Marina Raskova and Valentina Grizodubova across the Soviet Union established woman's place as an aviator once and for all. During the war Valentina Grizodubova was in command of an all-male regiment of long-range bombers. There is a photograph of Lily Litvyak in the Museum of Aviation and Cosmonautics. She is shown standing beside an astonished German ace. When he was shot down over Stalingrad the hitherto unvanquished flyer wanted to see the man who had shot him down. That was when a nineteen-year-old girl in a sheepskin coat walked in.

During the war years thirty women flyers were awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. One of them, Nina Raspopova, is especially close to Zinaida Petrovna's heart, for she was one of her pupils at the flying school.

Last autumn Zinaida Petrovna moved to Moscow from Kirghizia. Her friends inquired whether she would not prefer to go by train. The reply was: "No, I'm going to fly."

The IL-18 was taking the country's first woman flyer to Moscow. Naturally, no one paid any attention to the elderly woman who had a seat by the window.

"Is this your first flight?" the stewardess asked.

"Yes. My first in thirty-three years."

Zinaida Kokorina's life took a sudden turn, and she was compelled to stop flying. "At first, I thought I would be unable to bear it, but then I got used to being grounded, and life took on meaning once again."

She lived at Lake Issyk Kul in Kirghizia and taught school there for thirty years. "The past was gradually forgotten. At times I would think that I had never flown, that it had all happened to someone else. But now it has all come back to me."

We sat talking for eight hours, warming up the kettle from time to time to have another cup of tea. Zinaida Petrovna did most of the talking. As I listened, I could not help being amazed by her vivacity, wisdom and charm.

"My daughter hardly remembers her father. He was a flyer, too. He left for the East, and for many years I thought he had perished there. His portrait hangs beside that of Richard Sorge in a gallery of honor. They both worked together."

"Do you have any special request?" I asked as I was preparing to leave.

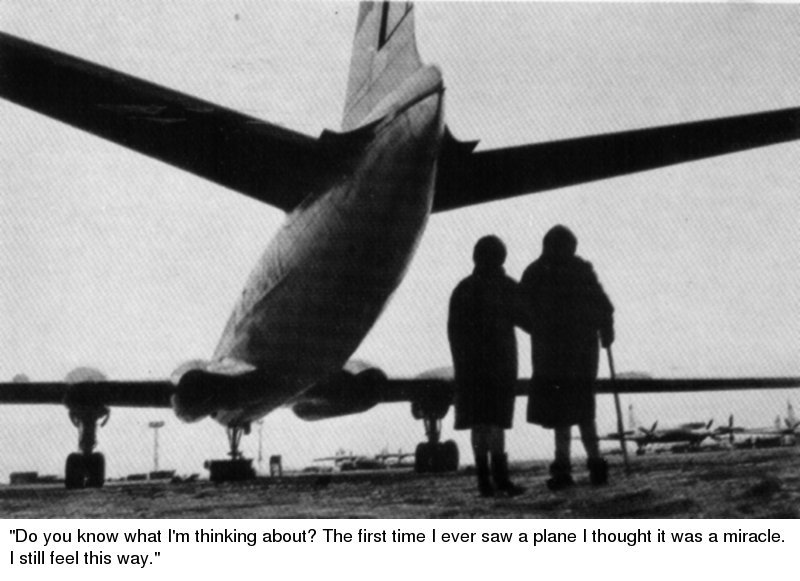

"Yes. Would you take me to the airfield? I want to have a good look at the new planes."

Soon after we drove out to the flying field at Vnukovo. It was a dismal day. The planes disappeared in the cold gloom the moment they took off. Zinaida Petrovna needs the aid of a cane and someone to support her other arm.

"Do you want to know what I'm thinking about? The first time I ever saw a plane I thought it was a miracle. I still feel this way. And I've been wondering whether I would have begun all over again if I were twenty today. Yes, I would."