We were sailing down the river in a motorboat. I can't help smiling now when I say "sailing". Even in the deeper spots the motor could barely turn over in the face of the onrushing waters, while at the rapids we had to climb out, shoulder a rope and drag it. That's what everyone does when they're moving against the current here. You keep on pulling, while the rocks roll away underfoot, the rope bites into your shoulder and your feet quickly become numb in the icy water. The best cure is a run along the dry pebbles of the bank and a smoke. However, we were in a hurry, and so kept on going. We turned on the motor in the deep spots where the river did not foam. It was a sore trial to us, for we kept waiting for the screw to hit against a stone and the key to break, which would mean time out for repairs. Though the key did brake at least eight times we still managed to cover about forty kilometers. After that something really went wrong. Volodya, our mechanic, first cursed in Russian, then in Koryak, rubbed out his butt in the aluminum bottom of the boat and said: "It'll take two days to fix it."

This was a blow. A plane was expected in two days' time, and I had to be back in the settlement by then. It was drizzling. Higher up in the mountains the rain appeared as foamy white snow. During the night winter might descend. We sat down to have a bite and to think it over. Then we spotted the boat. It was moving quickly downstream. There were three men in it. One seemed to be asleep, another was rowing and a third, the tallest, sat on the bow, holding a long pole. We shouted and waved. The boat turned towards the bank.

"He has to get back to the settlement. Will you take him on?"

"All right. Get in. Can you row?"

The boat was immediately caught up by the current. Then only did I notice I was sitting on a pile of large fish. There were also deerskins and venison on the bottom. A dog crouched in the bow. The large boat seemed about to draw water, but the old men were not worried. They were mumbling a Koryak song.One of them was drunk and was trying unsuccessfully to tie a thong on his greasy fur pants.

"Been to a feast ?" I asked.

"Yes. We had venison and mushroom wine," the tall man with the pole replied.

I had heard about this drink made of mushrooms. As I realized the nature of the river I got a firmer grip on the oars. The boat might turn over at any minute. I tried to recall how many shoals there were ahead. I had to gauge each stroke, but who could tell where to zig-zag through those crazy rocks. What a current! It had turned the boat sideways and was dragging it along.

One of the old men behind me was chomping on a piece of half-cooked venison with his toothless gums. The second man finally gave up trying to tie his thong and sprawled out on a deerskin.

"Grandpa Oni's sleeping," the tall man with the pole said and smiled.

I did not feel like joking. I stared at the tall man. Certainly he at least realized that we might turn over at any moment?

"How many loach did you get?"

"It's a good catch. About two hundred."

The water reached to the top of the sides. The fish under me slipped around as if they were alive. It was practically impossible to row. The man with the pole seemed to have sobered up, for he was wielding his pole expertly. Why then did he feel around for his mitten when it lay in full view on his lap ?

"Do you have trouble with your eyesight?"

"I'm blind."

"What?"

"I've been blind since childhood."

Sweat broke out on my forehead. I should have guessed. Indeed, his eyelids never moved, nor did his face. Just then I had to decide which way to turn the bow. I could hear the water hitting the rocks and could see the white foam. I had to decide quickly, in an instant. When we reached the rapids it would be too late.

"Melgitanin *Russian man (Koryak), use your right oar. It's deep over there near the bank."

By then I could see that was what I had to do. Soon my oar scraped the bottom again. I could not take my eyes off my companion as he kept steadying the boat with his pole. He had a white waffle-print towel around his neck instead of a scarf, and a knife and two small boxes were attached to his belt. One probably contained tobacco and the other some dried mushrooms.

"Did you drink at the feast, too?"

"Just a little. To make my insides sing. Use your right oar! There's a log over there."

If we had bumped into it. . . I could not contain my amazement.

"How did you know?"

"It's easy. I hear the noise the water makes. There's a bend up ahead. Steady! Keep her steady! Watch out for the rocks!"

It was too late. The boat did not overturn, but settled firmly on the bottom with a loud crunch. The pole and oars were of no use now. My helmsman jumped into the water. I followed suit. The water was higher than our boot-tops and ever so cold. Grandfather Oni was awakened by the jolt, but could not comprehend what had happened and so resumed his song.

Soon we were on our way again. I no longer felt I was the captain of this ship, and though I had to keep a sharp eye on the river, I followed every command uttered by the amazing man on the bow.

"Don't worry. There's no rocks here. Keep rowing. There's a lot of fish here. Can you smell the ukola? This is where I fish."

A neat barn on stilts came into view.

"Have you put in a good store for the winter?"

"Yes."

"Did you catch it all yourself?"

"My son helped, and my wife, but I caught a lot. Left oar now. There's a rock under the water here."

"Do you know the whole course of the river by heart?"

"I remember the way it sounds. The noise is different in every different place, and the pole makes a different sound, too. That's how I remember the depths."

"What's on the right bank here?"

"A lot of shallow water and a lot of logs. There's an eagle's nest in a dry tree."

Just then two white-tailed eagles rose and flapped heavily off towards a nearby slope.

We had been moving in darkness for the past hour. The mountains had turned black. Their jagged tops were clearly etched against the sky. Beyond the mountains the horizon was a pale yellow, while the peaks were becoming inky-black. Darkness gradually enveloped the river. Finally, only two snowcapped peaks far to the left retained a rosy hue. We were now proceeding in utter blackness towards the last two rapids. Beyond lay the lights of the settlement.

"Be careful here," the helmsman said, rising up and throwing his weight on the pole.

We streaked over the rapids. The moment we turned the bend the village came into view.

"When did you go upstream to the herds, Ivan?"

"Yesterday. I started out in the morning and had tea with the shepherds in the evening."

"Did you walk along the bank, dragging the boat?"

"Yes."

"All alone?"

"No. I took my dog."

I looked back in my mind's eye and visualized the rocky bank dotted with sodden timber and large stones, cut across by numerous trickles and streams, with a man trudging along, pulling his boat. A blind man. It was a good fifty miles upstream to the herds. No, it was impossible!

The boat nosed into the soft bank. The helmsman quickly found the peg in the ground and tied up the boat. He called to someone. Two women appeared instantly from the darkness and began packing the fish into a large basket. Since this was no time for questions, I decided to put off the conversation till later and said goodbye.

"You were good at the oars, Melgitanin. I didn't think you could row that good."

His praise was greatly appreciated, for my arms and back ached and there were bloody blisters on my hands.

I headed down the street and then looked back. The two old men were chatting amiably while Ivan was changing his fur boots.

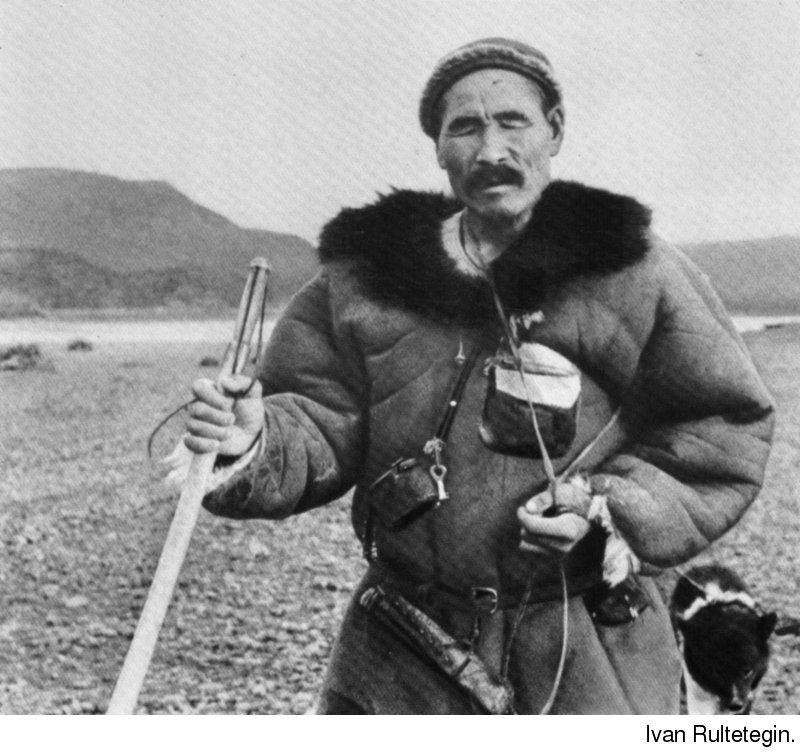

Forty-five years ago a Chukchi boy named Ivan Rultetegin went along with his father on a visit to a neighbouring herd. The grown-ups sat around drinking tea, while the children frolicked in the middle of the tent. Then their host's little daughter scooped up a panful of ashes in their датё ... It really seemed as if the fire had gone out in the hearth, but the ashes on top of the coals only formed a thin film. Later the women licked the ashes from his eyes and kept repeating: "Can you see?" He still remembers their anxious questions. He was six at the time and could not comprehend the enormity of his loss.

"Your ears, head, hands and feet will have to be your eyes now," his father had said. He took his son with him every time he went out into the tundra, commenting on everything they came upon: "This is a stream; these are a reindeer's tracks; this noise is made by ducks flying low; the grass under the snow is flattened towards the sun; if the birds begin to sing it means it's daybreak; if the sun is no longer warm and the wind has died down it means night has come to the tundra. If you remember what I tell you, you will live."

Ivan learned to recognize the presence of a herd by the smell of a campfire. He learned to lasso reindeer for his sleigh, to butcher a reindeer and skin it. He learned to sew fur boots, to make a good, sound sleigh, to choose the right tree from which to make a dugout, and to drive a dogsled, guiding himself by the direction of the wind. His father's eyes were always there to guide him. He could always say: why is this so? what is this? and receive an answer. Unfortunately, his father did not live long. He was caught in a blizzard and was buried under the snow for four days. He never recovered.

Ivan's best friend, Sergei Ivtagin, then took his father's place. They would set off bear-hunting together, or lie in wait for mountain goats, or hunt wild deer. Often it was Ivan who first heard the prey approaching. Then Sergei would fire. Ivan, who was tall and strong, would carry the carcass home. "No, I don't know how many kilometers that would be. Nobody ever measures distances in the tundra. Sometimes we'd be two days and sometimes three getting back." Ivan would shoot at a flock of ducks, aiming at the whistling sound of their wings. His dog would bring him the fallen bird. He could tell by the cry or the sound of the wings whether a flock of swans or geese was passing overhead or whether a bird was a magpie or a crow. He knew every stream around the nomad camps and when the salmon entered each. He was the best net-maker and an expert fisherman. His friend's eyes were always there to help him. Then Sergei married and moved away. "I got very depressed. I decided I would join my ancestors."

One day he took his gun and set off into the tundra, never intending to return. He walked on and on, not really trying to remember the way, since he would not be returning anyway. He would stop at times, not to rest, for he did not tire easily in those days, but simply to listen. A deer that had been resting jumped up at his approach. The hummocks felt springy under his fur boots. Ivan even enjoyed walking through the willow bushes that lashed at his face. He came to a stream and recognized its sound. This was where he and his father had fished. He crossed it, sat down and then heard a small creature splashing across it after him. It was his dog. Tuma ran up to him and rubbed against his leg. Ivan stayed on by the stream all that night, the following day and the following night. Tuma lay beside him. As he stroked his dog, Tuma would lick his hand. "Tuma, my friend," he said. Then he rose, crossed the stream and headed back home. He knew the way from the stream to the campsite. Besides, Tuma was leading him. Once among his people again, he said, "I went to listen to the tundra."

Life returned to normal. He could tend their herd alone for five days at a stretch and never lose a reindeer, for he now had a reliable helper. It was his dog Tuma. Ivan made a long leash, then hung a little bell on the dog's collar and could set off for firewood or berries, going far from the settlement. When Tuma had puppies he chose the strongest and brightest one of the litter and also named it Tuma, which means "friend" in Chukchi. Ivan Rultetegin married and had children. He now had a family to support. "There was a lot of work, all kinds of jobs to be done. My dog helped me in everything I did."

Tuma knew every path his master took when they went fishing or for firewood. As often as not, Ivan would get up and set out in the dead of night. Thus, they usually went for firewood at night. Tuma's bell tinkled ahead of him as the long leash led him on. They always returned home safely.

When the roads were washed out and neither the dog teams nor reindeers could pull a sleigh, Ivan would volunteer to bring any urgent goods to the settlement from the trading post on the coast. He would set out on foot in the morning and return with a heavy pack towards midnight, having stopped for two "tea-breaks" on the way. It was seventy-five kilometers from the settlement to the trading post, which meant he averaged eight kilometers an hour. "I could never have done it without Tuma."

For a while Ivan drove a dogsled for the travelling community center bringing newspapers and new films to the herdsmen. If they were ever caught in a blizzard he was their only hope. He would pull off his parka hood, listen closely, then scoop away the snow from the ground, touch the old grass underneath and say which way they were to go.

Tuma served him faithfully for eighteen years. In his old age he began getting confused. Ivan guessed that Tuma was going blind. "I became very depressed again." When Tuma became totally blind he could not even find his way out of the tent. Ivan did not shoot his dog, as he would have done if one of the other dogs had become old and sick. Instead, he cut old Tuma's meat in thin slivers and took him out for walks on his leash. Two years ago he buried Tuma at the foot of a mountain near the settlement. "There will never be another dog like him."

Ivan's eldest son, Terguvye Pavel, his fellow-herdsmen, his neighbours and he himself all told me parts of the story of his life. I dropped in to see him the day after our trip up the river. Ivan, who is now fifty-two, no longer travels with the herds. Each summer he goes upstream to a place known as Vai-Vaiyam ("the hay-growing place") to fish and lay by a store of ukola for the winter. In autumn and winter he works as a carpenter on the state farm. In the evenings, since "there are a lot of children, and they all have to eat", he makes fur boots, lassoes for the herdsmen, pipes and leather tobacco boxes.

The house was hotly heated. Ivan was sitting on an old reindeer skin on the floor, sawing away at a piece of bronze propeller from an old ship. Someone had brought him this find, knowing that Rultetegin could put anything to good use.

"This will make good lures. Some for myself, some for the other men. They bring me meat. I have to do something for them, too." He continued sawing the large propeller into strips as he spoke, gathering the shavings in a rag for some future use, too. The lights suddenly went out, but he continued working.

"How come your son Pavel is at home? I thought he was in Petropavlovsk."

"He was at college there, but I called him home. I said: 'You take one year off, Pavel, and help me a bit here till your sister graduates from school. Then you can go back to Petropavlovsk."

"Were you ever there?"

"No."

Two naked little girls were scampering about the house, shrieking delightedly as they tried to wrap a fat puppy up in a deerskin. A large dog lay in a corner, watching the commotion solemnly.

"How many children do you have?"

"Seven. Listen, do you have any film? I mean, any film you don't need ? Give Pavel a roll or two so he can practise. I bought him that little machine that takes pictures."

Venison bubbled in a kettle in the oven. Ivan's quiet wife was crushing blueberries and crowberries in a wooden bowl. Then she added fish and some yellow root vegetable to the berries. The two black-haired, smudge-faced tots kept racing around. One snatched a pinch of shavings from under her father's saw and sprinkled them on the puppy. The girls laughed. Meanwhile, their father continued working. His large, sinewy hands were bruised. Every now and then he would run his fingers over the area he was working on. His face had the tense, intent expression of a blind person, and when he spoke he tilted his head.

"My hands are tired. I'll switch to something else."

He pulled a length of deer gut from a leather pouch, brought it up to his face and, aided by his tongue, quickly threaded a needle. As I watched, a piece of reddish deerskin was transformed into a child's leather stocking or boot.

I never saw Ivan dance, but heard a lot about it. They said none of the young men could dance as well or as long as Rultetegin. He dances to a tambourine outdoors, or to music on the tiny stage of the local community center. He is also the champion wrestler of the Kamchatka tundra. No one has ever thrown him in a traditional wrestling match.

The next morning I saw Ivan leaving the village. He was straight and tall. Actually, I had never seen anyone as tall as he. He wore a red parka trimmed with black fur and carried a long stick in his right hand. There was a knife in a holster on his belt and a thin leash over his shoulder. A young dog ran on ahead, pulling at the leash.

The local radioman and I watched them.

"You know," he said to me, "Ivan can feel tracks on the ground and tell you whether they were made by a fox or a dog and whether they were made today or yesterday. He's an amazing man!"

We could hear the wireless beeping away through the open door, but the radioman was in no hurry to enter the little house filled with black cases of equipment. We stood watching the giant in the red parka climbing the slope at a slant.

"He's going into the tundra for something."