I have known Boris for over ten years, ever since I first decided to write about him. He was then doing graduate work in biophysics. However, when I told him how I had planned our interviews, he said, "No, I'm afraid it'll interfere with my work." I did not insist. We spent the evening in amiable conversation and became friends. We have tramped through the woods together many a time, and, as the Russian saying goes, have eaten much salt together. I know Boris well and want to tell you about him.

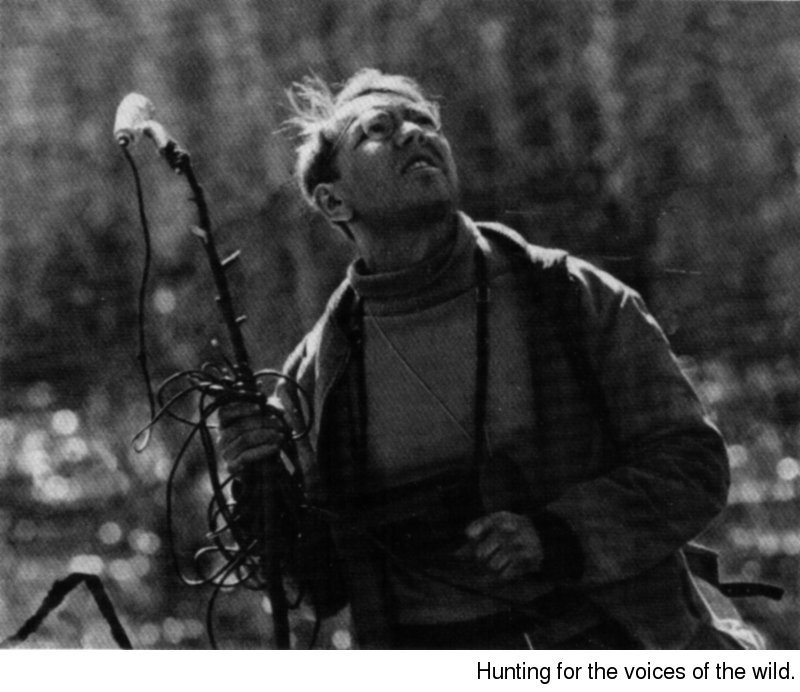

I lay down my pencil and listened to the record for the nth time. No, this was not music. But perhaps these sounds prompted the first human songs and, eventually, our own music. Indeed, everything must have begun with these sounds that still fill our woods and glades. Nothing can awaken our slumbering joy as they do, yet, how often does one take time off from a busy city life to venture into the green world of the forests, meadows and streams? Then one day a man came along who wanted to record all these forest sounds. All you have to do now is put on the record player and your house will be filled with the croaking of frogs, the cooing of a wild dove or the cries of a landrail.

The crying of a landrail. This is a sound very dear to my heart. It brings back memories of our cottage in the village, the picket fence around the yard, the old elms and the willow thickets shrouded in mist. Horses appear from the mist. And a landrail is crying. It is a simple, monotonous sound, but anyone who has once heard its cry in the fog will understand why I wanted to listen to the record over and over again. Then there were the cries of cranes. How many people can say they have heard the cries of cranes on the wing? Perhaps one in a thousand. There is also the song of a nightingale, of a thrush, a wood-grouse, the springtime tattoo of a woodpecker, the buzzing of a bumblebee. You can actually hear the forest breathing, the green whisperings of spring advancing across the earth. I want to tell you about the man who came forth to record these eternal sounds.

This voice-hunter is not a woodsman. The last time I saw him was in the little town of Pushchino-on-Oka that is fast becoming one of our country's scientific centers. Boris Veprintsev, a biophysicist, came here from Moscow, having been appointed the head of a laboratory in one of the new buildings. His field is in the front line of science. It is not easy to check on the accuracy of the words "front line", but they really do convey the meaning of everything that is taking place in the research laboratories. If one were to continue the simile, one could say that Boris is a front line company commander.The territory which his company has volunteered to win away from the Unknown is less than miniscule. It is the nerve cell, unseen to the naked eye. The human brain, nature's greatest achievement, consists of fifteen billion such cells. The eventual discovery of how the nerve cell functions and why it dies will be a tremendous breakthrough, perhaps even greater than the splitting of the atom.

The company commander often comes home after work so tired he cannot fall asleep. Then, in the morning, as he is frying eggs, he will suddenly pull a few sheets of blank paper from his pocket and jot something down. Or we might be out in a boat and he will lay down his oar and stick his hand into his pocket for a clean sheet of paper.

Boris belongs to that category of possessed scientists whose Monday begins on Saturday, meaning that the weekend, a holiday or any other time is just the right time for work. Such people are often a bit eccentric or absent-minded in their daily lives. However, experience says we must have faith in them, and I do have great faith in my friend. Now I shall go on to tell you of his great passion and of what one can do for others "in between", so to speak.

One cannot call this a hobby, for a hobby is something one does for personal pleasure. In this instance it is a childhood dream, cherished and preserved despite all adversities.

Thirty years ago Boris was a member of the Junior Biology Club at the Moscow Zoo. One day he attended an especially interesting lecture. After the lecture the late Professor Promtov went over to an old-fashioned gramophone and cranked it. Suddenly the packed auditorium was filled with the sound of a nightingale's song. This would not amaze us, who are so used to tape recordings. At the time, however, learned scholars rose and applauded, shouting: "Once again!" like children. A boy sat in the last row, taking in every sound of the amazing recording that had been made in England. Professor Promtov said: "There's an old man named Ludwig Koch who lives in England. He emigrated there from his native Germany to escape the nazis. Koch records the voices of birds on wax discs. Every schoolboy in England knows about him." The professor went on to say that he had tried unsuccessfully to make some recordings."However, we must not give up," he concluded.

War broke out. Everyone probably forgot the unusual recording, but not Boris. He remembered the nightingale's song and Ludwig Koch, who seemed to be a character out of a fairy-tale. Boris took apart his family's record player on the sly, hoping to build a "recording machine". Naturally, nothing came of the venture. Still, the boy had a right to experiment, for at thirteen he was not only passionately interested in ornithology, but could also drive a car and fix a broken radio. He got a job in an army hospital as an electrician. There, to the amazement of his elders, he fixed a lot of broken medical equipment. Indeed, boys matured quickly in wartime.

"I could never get rid of this strange desire to record the voices of birds," Boris said. "I'd hear a sparrow chirping and say to myself: there's a job I have to do. I'd recall the rivers overflowing in. springtime, the orchards and the forest and never doubted that some day my dream would come true, because the first tape recorders, those fantastic apparatuses, had by then appeared on the market."

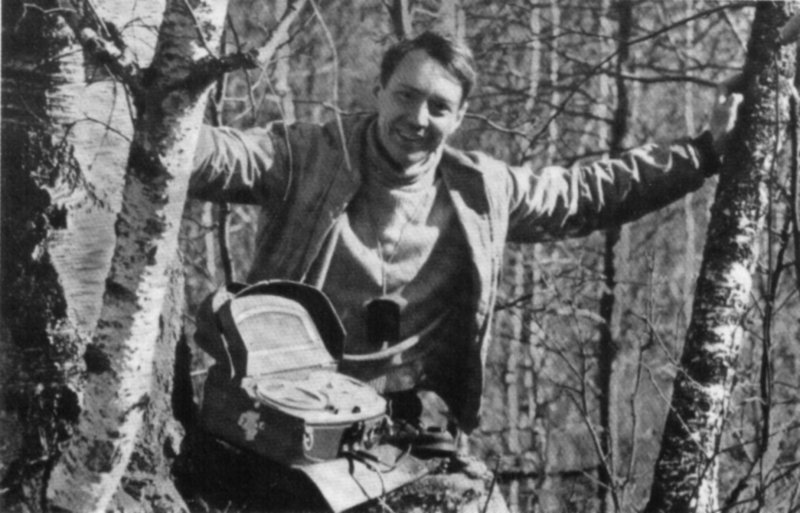

In the spring of 1956 a man sat by a strange-looking box on a dry clearing in the woods near Zvenigorod. Something seemed to be wrong. He removed the lid and bent over the box, checking on the electric wire that led back to one of the cottages of the biological station. Another apparatus was hidden in a birch tree on which a finch was singing. A shepherd watching the goings-on from afar was finally overcome by curiosity and approached.

"What are you doing?" he asked.

"Listen."

"Hm. That's funny. Sounds like a finch to me. Is it?"

Boris continued his story. "To tell you the truth, the recording was worse than fair, with the finch coming through faintly over a loud hum. But I was ready to shout from joy. I detoured to Zvenigorod so that a friend of mine there could hear it. Then, while I was waiting for the suburban train, I asked the girl standing next to me whether she had ever heard a finch's song and played it for her. When I reached Moscow I played it for my professor and for the fellows at the dormitory. The following week I'd put on my earphones and listen to it before going to bed each night."

It's a very long way from the "first finch" to the summit in any new undertaking. For the next three years Boris, then a student at the University and later a graduate student, pottered around with his box, since the ordinary type of tape recorder was unsuitable for the project. He actually had to design a new type of tape recorder. This is where Boris' old passion for electronics came in handy. His friends, all engineers working in the field of sound recording, came to his aid. Their goal was a recorder that would pick up the slightest sound, not produce any hum, would be small enough to fit into a knapsack with all its many attachments, would withstand jolting and dampness and be completely reliable.

Boris translated articles from English and German for scientific magazines for two winters. He also translated two books. The proceeds all went into his "box". The end result was magnificent. However, he picked up a buzzing during a tryout. Was this some new defect? No. A fly had come to life in a warm corner and was caught in a cobweb. The recorder had immediately taped its frantic struggles, for it picked up every sound within its range. One morning in March Boris stuck the microphone out of the window and recorded the din some blue titmice were making. The next day he decided to give the birds a playback of the previous day's commotion. He was more than surprised to see them winging towards the recorder from all over. They perched on the loudspeaker, chirped and were very excited. When he switched it off they fell silent and then flew away. A starling whom Boris held by its wing in front of the mike babbled such terrible things into it that when he played the recording near a birdhouse in which starlings lived the inhabitants flew out in a panic. This simply corroborated the old belief that birds had a language of their own beside their traditional songs. Now a hunter had come forth who was after these songs and the sounds of spring that have always made one's heart beat faster.

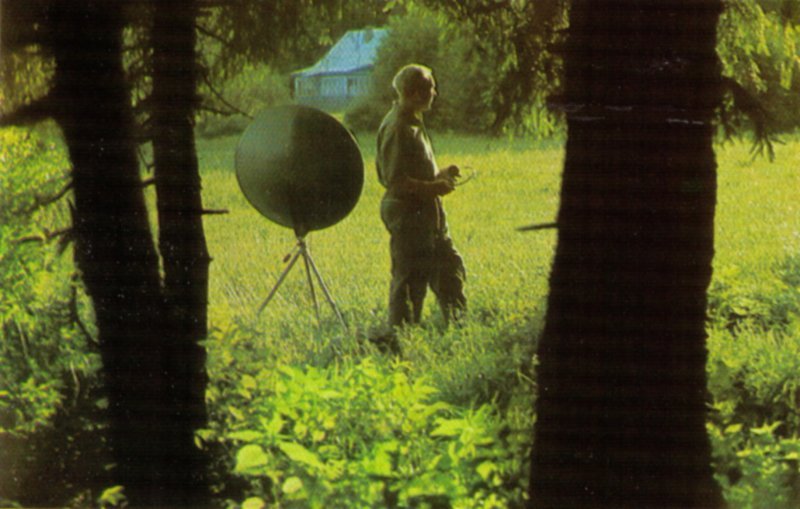

The scene was a May night on the Oka River. The grass was wet from dew. Landrails called out in the dark. The meadow was covered by a spring fog, and the campfire at the water's edge was dying down. A cock crowed in the distance. Drops of water fell into a puddle from the needles of a spruce. The reels spun silently. A dew-drenched man lay in the grass. He had on a pair of earphones. The night with its many sounds was being wound up on a narrow strip of tape. At daybreak the number of sounds increased, for even the voiceless greet the sun with a song. A woodpecker perched on a dry branch. A moment later the tat-tat-tat of its drilling filled the woods. A tiny snipe flew high up into the air and then hurtled earthwards, the wind whistling through its wing feathers producing a bleating sound. A thrush sang and a cuckoo called. The man's eyes were heavy after a sleepless night. As the sun warmed him he dozed off without even bothering to remove the earphones.

Then Boris began hunting for voices in earnest. It was not as easy as he had imagined. A bird's finest song is heard at daybreak.That meant he had to choose a spot in advance, knowing for certain where a given bird would be. Boris spent many a night on flooded islands. There were times when in his excitement he would not get any sleep for three nights in a row. He journeyed through the countryside around Moscow, standing for hours on end in some marshy spot, climbing trees or crouching in a blind, waiting for black grouse or for his singers to perform. From the very first he discovered how many obstacles there were: an accordionist might begin to play outdoors in the evening in some village near his vantage point, a cock might crow, a river boat might suddenly appear, churning up the water, its whistle rending the air, or the wind might rise, or the singer he was hunting might not let him get close enough. The nightingales were a special problem. No matter where he went their singing drowned out all other sounds. He would have to retape a song time and again, choosing a different spot, standing in water again, searching, creeping up stealthily, and getting rid of the bugs in his tape recorder in the woods at night by the light of his flashlight.

Finally, the day of rejoicing arrived. The following announcement was made at a conference of ornithologists: "You will now hear some bird voices." A black grouse gave its mating call. It was followed by a cuckoo. Wild geese honked and thrushes sang. The applause was deafening. The graduate student's work had earned this acclaim.

Boris Veprintsev was then asked to cut a record at a recording studio.

The record went on sale in April 1960.

It stood on a shelf next to symphonic music in the record department of a large store on Gorky Street in Moscow.

This was a happy day. Boris mailed copies of the record to his friends. He had not forgotten the old man in England and sent one to Ludwig Koch. He did not know whether Koch was still alive or not, he really did seem to be a fairy-tale personage.

Three weeks later he received a reply. The letterhead bore a picture of a bird drawn on a record.

Ludwig Koch thanked Veprintsev for his wonderful recording of the voices of Russia's birds and said that the day on which he first listened to it had been a memorable one. He said he was now retired, being eighty, and had entrusted the younger generation with the task of recording the voices of birds and beasts. Koch said he had recently been feted and had received many congratulatory letters and telegrams from all over England. He thanked Veprintsev for having given him the opportunity of listening to the voices of birds that have become a rarity in England, birds such as the black woodpecker and, especially the quail. Koch said that he knew from his study of music that many composers of the past were inspired by the call of the quail, and this was certainly true of Haydn. He said that the gray crane was no longer to be found in England and that he would appreciate a recording of its call, as he felt it was one of the most beautiful sounds on earth. In conclusion, Ludwig Koch thanked Veprintsev again for having remembered an old man.

There were many other letters, too, and the message in all of them was: THANK YOU.

By 1962 the first record had gone through several editions. The hunter, encouraged by success, spent all his free time in the woods and fields. In winter he taped the howling of wolves, and late in February he crawled through the snow to catch the mating calls of ravens. He travelled throughout the country, to the bird colonies of Kandalaksha Bay and the Far East, to the Caucasus to tape the mating calls of deer. That spring I accompanied him to the Meshchera forests to tape the calls of cranes.

Everything was under water for as far as the eye could see. The water reached halfway up the trees. Hares had found refuge from the flood on little islands and snags. That night we were going to tape the hooting of the wood owl on a large island. Since the bird would not let us get close enough, we decided to outsmart it. Ludwig Koch had sent Boris a record. The owl's hooting on it was very clear. All was still that night. As soon as we heard the owl in the distance we switched on the voice from England. This was the voice of a rival, and our bird immediately rose to the bait. Soon it was within range. The wood owl perched on a willow and tried to drown out the intruder, while the reel with the original recording kept spinning in a knapsack.

Cranes honked over the flooded forest every morning, but the cautious birds bypassed the island, so that we could only catch their calling from afar. We then set out to search for them in a fold-boat, looking in the flooded forest cuttings and meadows and occasionally dragging the boat over dry land. The wary eyes of forest mice, snakes and turtles watched us from the tree stumps and snags. Black grouse called in garbled voices on lone trees in the clearings. I rowed slowly, while Boris pulled a mitten over the mike (to block out the sound of the wind) and held the long pole closer to the singer and farther away from the spinning reels.

Towards evening we came upon the cranes' resting place. It was a rise covered with bushes and last year's grass. Five cranes were fishing in the shallow water. They stretched their necks in our direction and then began walking quickly away. One took off. The others followed, honking loudly. Just then something went wrong in the accursed recorder! The cranes seemed to be teasing us as they circled over the clearing. Boris spread his sheepskin coat on the grass and snatched out a screw-driver, but it took him an hour to locate the bug. We then pitched our tent and went on a tour of inspection, discovering we would have company at night, for two hares and a weasel had also found refuge on the hill.

The following morning I was awakened by the sun. I opened my eyes and held my breath: five cranes and the hares were passing back and forth no more than twenty paces away. The cranes walked with a sort of a hop. They ignored the hares completely. We were afraid to move. Boris switched on the box under his coat and cautiously put on his earphones. The birds noticed the movement and rose, shrieking loudly. One nearly hit its wing against the mike. However, all was well. Boris looked very intent. Then he winked and tilted his head, and I could see he was hearing their cries in his earphones.

When we built campfire to dry our clothes the hares scampered off to the far edge of the rise to escape the smoke. Our bread tasted wonderful. Boris put on his earphones again as we were eating, seemingly to check on something, but I knew he just wanted to hear the cranes again. I turned away. Sometimes the cries of cranes have a very powerful effect on a person.

As we were talking about records one day, one of my friends at the office said, "Look at this letter I got." It was from a friend in Italy and read, in part: "Don't take any extra luggage. Bring us some black bread and, if you can get it, a record of birds' voices."

I was not surprised. When I was preparing to go to the Antarctic seven years before I had asked people with experience what to take along as gifts. One of the several items mentioned was "a record with the voices of birds on it, if you can find it".

Indeed, it proved to be the best gift of all. I watched the people at one of our distant embassies listening to it. A foreigner who was presented with a record exclaimed: "You mean these are the birds that sing near Moscow?" The radioman at the Antarctic station announced : "And now, the voices of home." Imagine a snow-bound settlement with several radio antennas and an aluminum loudspeaker on a pole protruding over the rooftops. Suddenly a bird begins to sing amidst the vast expanses of snow and ice, bringing the green voices of early spring to the Antarctic. Nor shall I forget the faces of those who listened to cranes calling out in the icy wilderness. Could there have been a better gift for these polar explorers?

I have before me a pile of letters addressed to Boris Veprintsev. One is from a schoolteacher in Yaroslavl, another from a group of children in the Crimea, some from a zoologist in Leningrad, a scientist in Sweden, a game warden in Nairobi, one from Prince Akihito of Japan, who is interested in ornithology, one from the director of the film War and Peace, one from Yuri Ivannikov, a captain of a ship, one from Valentin Gridnev, an engineer in Chelyabinsk ("I'm, usually dead tired when I get home . . . Your forest voices are like vitamins for the soul."). There are many hundreds of letters. The voices of birds serve as a textbook for some, the call of their distant homeland for others, and an object of curiosity for still others ("Imagine! Birds from Moscow Region!"). Someone else may want them for the soundtrack of a film. To the majority, however, they are "like vitamins for the soul".

To date, five records have been released in thousands of copies. The demand is great. Czechoslovakia ordered twenty thousand and Poland fifty thousand. The records have been included in international catalogues. They were sent to the World Fairs in Montreal and in Tokyo along with other Soviet treasures, for they are indeed a national treasure, as are the first collections of proverbs or folk songs.

I was wondering how best to end this article and discovered I need not try to think of anything special. My record player and one of the bird records stood on my desk. I put the record on and a cuckoo began to call. The window was open, I could see a young girl on the balcony of the house opposite peering at a tall poplar. She seemed to be saying to herself: "A cuckoo? It's too early in the year for a cuckoo..." But it was a cuckoo! I could see her beginning to count, according to the old belief that the number of times a cuckoo calls is the number of years left to you. The girl may never have seen a cuckoo in her life, but there is no one who does not know this simplest of songs. I wanted her to count many years ahead and so set the needle back again and again. Indeed, she was counting. Then an old woman joined her, said something, cupped her ear and began counting, too.