Introduction

Recently I have been coming across a lot of discussion of stress, in books, studies, podcasts and online.

It is not surprising because stress is one of the modern fixations of society and the media loves it.

As a result it has been prominent in my mind.

I have been thinking a great deal about my own personal experiences of stress, my observations in other people and what I have read in the medical literature.

This post is a combination and distillation of those thoughts.

This is a long post, if you are pushed for time please scroll to the bottom for the "Conclusion/TLDR" version.

What is Stress?

My personal (simplified) definition of stress would be that it is the response of your body and your mind to fear.

In Palaeolithic times (the stone age) this would have been an overt threat like being attacked by a tiger or a rival tribe.

In order to defend yourself or run away (fight/flight) your body would produce a large amount of certain hormones called stress hormones.

These are called cortisol, adrenaline and noradrenaline and help to optimise the body for (short lived) bouts of extreme activity.

That way you can run faster or fight with more strength for long enough to save your life.

Once the situation was over these hormones would then return to normal and assuming you weren't seriously injured or killed you would live on to to fight/run another day.

Due to the nature of life in ancient times these would be short lived situations and assuming you survived your body would likely have plenty of time to recover for the next such situation.

Modern Day Fears Are More Complex

In the modern day our "fears" are more abstract and are not necessarily as quickly resolved as they were for our Palaeolithic ancestors.

Although "civilisation" and contemporary life has changed a lot about our lives, the way our bodies respond to fear is exactly the same way as in ancient times.

It doesn't matter if the threat is a tiger attacking you, getting fired from your job, or finding out your spouse is cheating on you.

Our bodies respond in exactly the same way by producing large amounts of stress hormones.

Whilst having this happen occasionally from time to time does not do any harm, having this stress response multiple times throughout the day, day in day out can become a problem.

The types of problems we deal with in modern times are not immediately life threatening but without the context and perspective of those life or death situations we have tendency to treat them as if they are.

We focus on them and ruminate on them.

The more abstract and intellectual nature of the problems also means that they can't be as easily or quickly resolved as those ancient human survival situations.

You can't fight your way out of a bad situation at work by clubbing your boss to death.

Well you could but you will end up in jail for a long time.

This creates a problem. There is a reason that the human body doesn't produce stress hormones all the time naturally.

The extra energy expenditure and various other changes put more physical stress on your internal organs.

Think of it like removing the safety restrictions that normally prevent an engine from over-revving.

It is worth it in a life threatening situation.

Your body will take the risk of increased damage in order to save your life.

If it only happens occasionally and with large enough gaps in between then your body can recover without any long term problems.

The real problem comes when you keep shifting into this mode on a regular basis - this is chronic stress (chronic just means something that takes place over a long period of time).

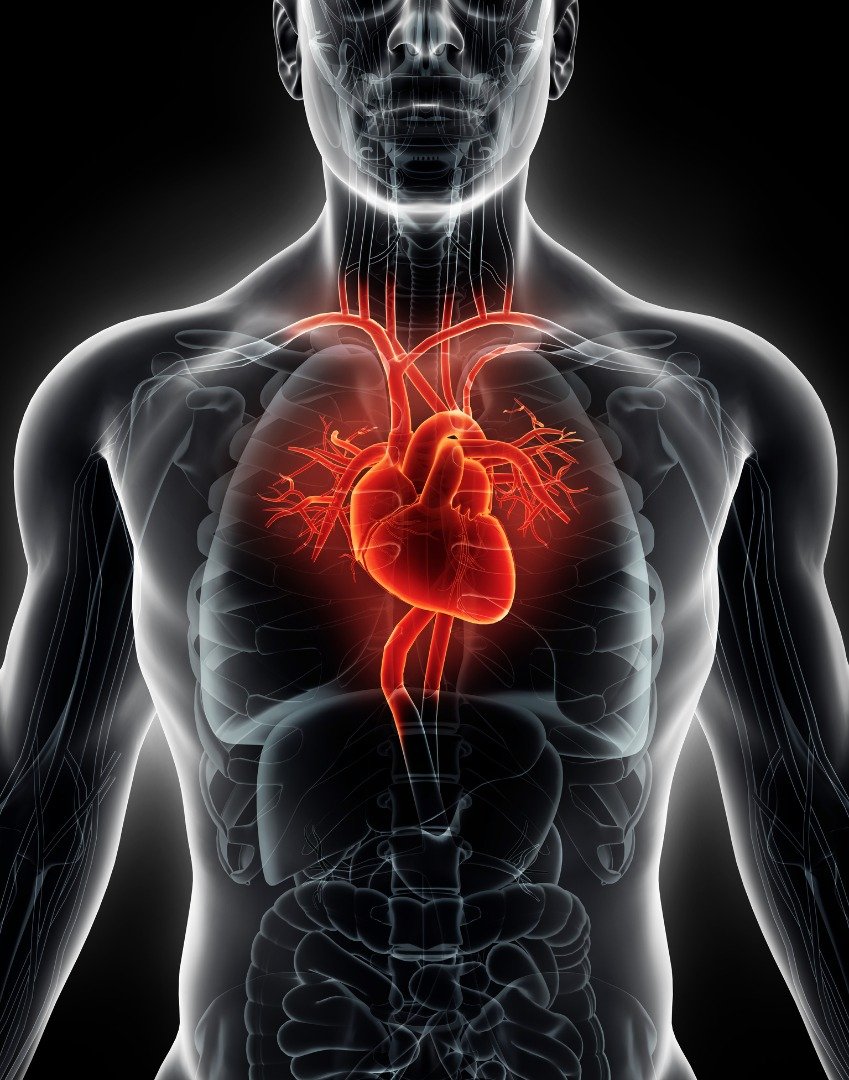

Some of the greatest burden is on your cardiovascular system, particularly your heart.

There is even a condition known as Stress Cardiomyopathy (Tako Tsubo Syndrome) where it appears that stress can lead to sudden death [1].

I recently posted on this subject when discussing whether it is possible to die of a broken heart - it seems in certain cases it is.

Another organ that seems to suffer a lot from prolonged stress is the brain.

There is a vast body of evidence that suggests that there is an association between stress and mental health problems like depression, bipolar disorder [3] and even schizophrenia.

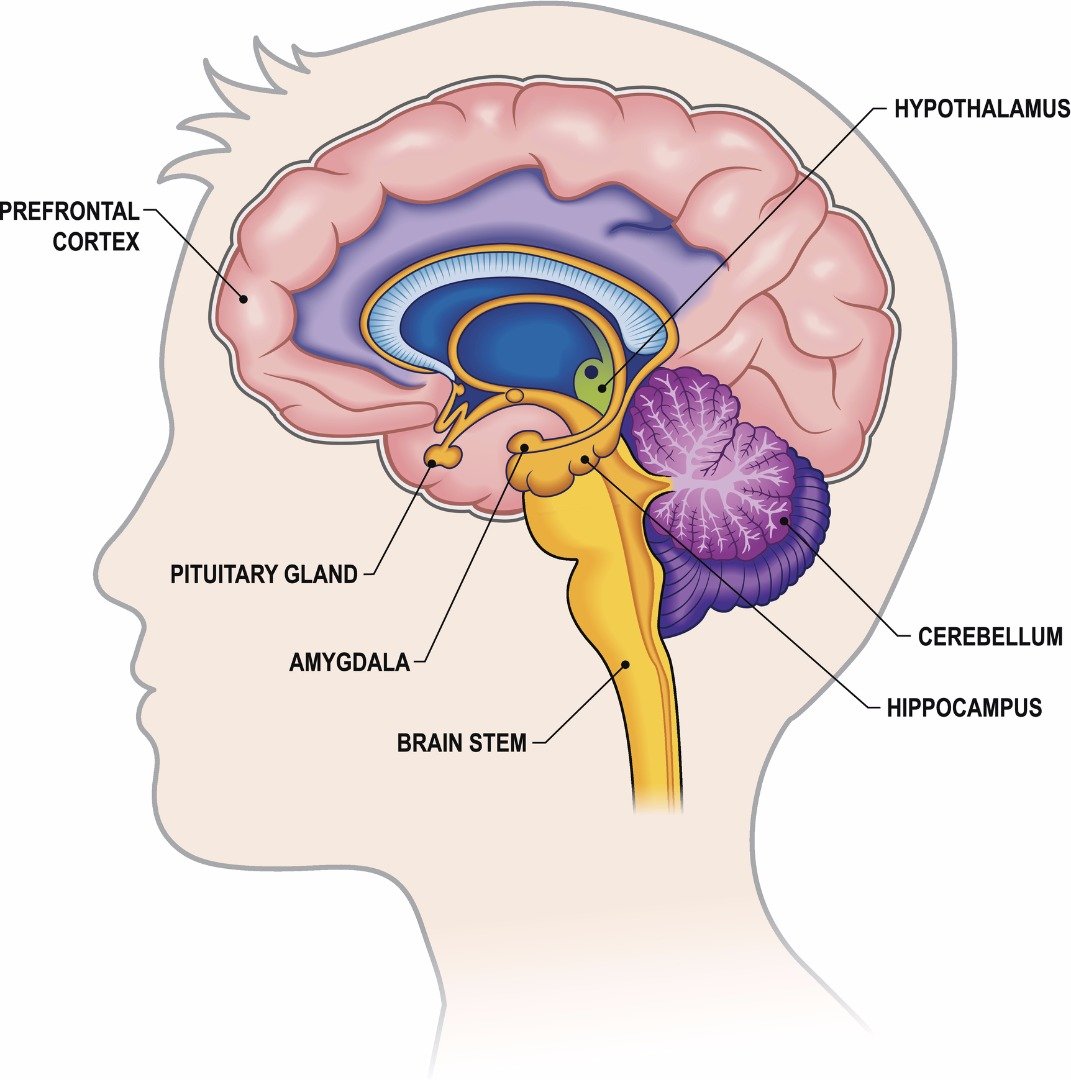

Even mild stress over a long period seems to cause changes in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex - brain areas implicated most strongly in depression [4] and other mental health problems.

According to a systematic review by Calcia et al [5,6] there is evidence from multiple studies which suggests that these areas of the brain are most sensitive to the effects of stress.

So How Can We Deal With Stress?

Recently I posted about Mark Manson's book "The Subtle Art of Not Giving A F*ck".

In the book Manson makes an important point. It is impossible for us to remove stress from our lives completely.

Stress is a natural part of lives.

I think the problem comes when we have prolonged stress and we don't deal with it in a productive manner.

There are a vast amount of things in our lives which we have no control over. Bad things will happen to all of us - frequently. There is no getting around it.

Most of us may also have noticed that there are people that we encounter who seem to be unflappable, no matter what situation or difficulty they find themselves in.

These people don't stress out at least not to the same degree. Are they some kind of freaks of nature who don't feel fear at all?

It is possible, even likely, that some of them have a genetic predisposition to respond differently to stressful situations. It is also possible that some of them are psychopaths or sociopaths.

I believe there is more to it though and I have observed this myself in people who undergo medical or emergency training.

They may start off fearful but as their confidence grows and they get used to dealing with difficult situations, they tend to get less stressed out - or at least some of them do.

What is the difference between those who do and those who don't?

I believe it is a matter of:

How they frame these situations.

How they refocus their energy into taking positive action.

The sense of "control" that the above two points create [7].

Framing, Positive Action and Control

Let us take an extreme example. You step outside your door and see a horrific car accident involving multiple casualties.

You can't prevent the car accident because you can't roll back time and even if you could you can't control what other people do.

Rather than focusing on worrying about things which you have no control over - it is better to concentrate on the things you can do something about.

All you can control is what you do. In this situation it would mean trying to help by checking the injured, delivering first aid, calling for help etc.

The person who takes positive action like this will likely feel a lot less long term stress than the person who panics and does nothing.

Why?

On the one hand they will be taking positive action during the stressful situation - giving less of a chance to worry over the minutiae of it.

Secondly they are creating a more positive experience during the course of a more negative one.

The net effect I believe is to encode less negative memories in the midst of a negative situation.

Remember how I said that the hippocampus is one of the areas that is most involved in mental illness and seems to be particularly susceptible to stress?

Well one of the major functions of the hippocampus is in the regulation of memory [6].

This suggests that alteration of memory encoding is one of the features that may increase the toll that stress takes, resulting in mental illness.

We can't necessarily control this susceptibility but we can control the memories which we encode - if we make those more positive and productive we can help to reduce the negative impact.

At least that is my personal theory - I don't think all of the evidence for this has been combined in this way, at least not yet but it is hard to be aware of all the literature.

Anyway this may seem like a pretty obvious situation because it is so extreme. There is little argument for how you need to deal with it.

The point is that we have lots of metaphorical car crashes going on in our lives.

We can choose to do nothing in which case our stress will count for nothing and likely increase or we can choose to do something.

By doing this we re-frame the situation from one of helplessness to empowerment and we replace negative memories with more positive (or at least less negative ones).

By doing this we are also actively demonstrating to ourselves that we are the kind of person who can cope with adverse circumstances.

We take control of our own destiny.

This helps to create a more positive narrative in our lives and will feed into more positive thoughts about ourselves which will in turn lead to more resilience and greater ability to cope with stress.

Like many things which occur in relation to thinking it creates a positive feedback loop which constantly feeds back into itself.

Summary of How to Deal With Stress

So taking the points from the last section here is how I would suggest dealing with stressful situations (indeed this is what I am trying to do myself):

Reframe and Refocus - from what you can't control to what you can.

Take Positive Action - so you encode more positive memories.

It sounds simple and obvious but it is not easy to do if you are not used to it - like most things you have to train yourself to do it through repetition and practice.

If you have learned to spend most of your life running away from problems it will be particularly difficult.

There is nothing to lose from trying it though.

Conclusion/TLDR

The key point is that there are many things in life that we cannot control.

These will inevitably cause us stress.

Pretending or expecting to be able to prevent them will likely make the stress worse and make us feel helpless.

The idea that we should be able to control everything and have comfortable stress free lives is not only patently childish, it also paradoxically makes us feel worse.

The one thing we can definitely control is ourselves and how we respond to these situations.

By concentrating our focus on what we can do, we reframe the situation and enable ourselves to act and produce more positive memories.

This then feeds into preparing us and training us to deal more effectively with future stressful situations which creates a positive reinforcing effect on our lives.

The more we are able to do this, the less our perception of the severity of stress becomes and hence the negative impact on our health and well being is reduced too.

Anyway what do you think?

Feel free to share your own personal experiences and thoughts in regards to this subject.

Thank you for reading

References

Sinning, Ch, T. Keller, N. Abegunewardene, K-F Kreitner, T. Münzel, and S. Blankenberg. 2010. “Tako-Tsubo Syndrome: Dying of a Broken Heart?” Clinical Research in Cardiology: Official Journal of the German Cardiac Society 99 (12): 771–80.

Willner, Paul. 2017. “The Chronic Mild Stress (CMS) Model of Depression: History, Evaluation and Usage.” Neurobiology of Stress 6 (February): 78–93.

Lex, Claudia, Eva Bäzner, and Thomas D. Meyer. 2017. “Does Stress Play a Significant Role in Bipolar Disorder? A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Affective Disorders 208 (January): 298–308.

Howes, O. D., and R. McCutcheon. 2017. “Inflammation and the Neural Diathesis-Stress Hypothesis of Schizophrenia: A Reconceptualization.” Translational Psychiatry 7 (2): e1024.

Calcia, Marilia A., David R. Bonsall, Peter S. Bloomfield, Sudhakar Selvaraj, Tatiana Barichello, and Oliver D. Howes. 2016. “Stress and Neuroinflammation: A Systematic Review of the Effects of Stress on Microglia and the Implications for Mental Illness.” Psychopharmacology 233 (9): 1637–50.

Lazarov, Orly, and Carolyn Hollands. 2016. “Hippocampal Neurogenesis: Learning to Remember.” Progress in Neurobiology 138-140 (March): 1–18.

Sherman, Gary D., Jooa J. Lee, Amy J. C. Cuddy, Jonathan Renshon, Christopher Oveis, James J. Gross, and Jennifer S. Lerner. 2012. “Leadership Is Associated with Lower Levels of Stress.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109 (44): 17903–7.

Follow me on Steemit: @thecryptofiend & on Twitter : Soul_Eater_43.

All uncredited images are taken from my personal Thinkstock Photography account. More information can be provided on request.

Before you go have you filled in the Coinbase form to list STEEM? It only takes a few seconds. THIS POST shows you how.

Are you new to Steemit and Looking for Answers? - Try: