Introduction

It would seem fairly obvious that our diets have a big effect on both our mental and physical health. It is therefore surprising that this is something that has not been studied in a lot of depth until recently.

Most older research takes account of specific dietary deficiencies and their effects on mental and physical health.

It is only in recent decades that there has been more consideration of overall dietary quality and it's relationship to conditions like depression.

It is something I am interested in because I think it not only relates to overcoming nutritional deficiencies but is also likely tied in to one of contemporary medicine's hot topics - the microbiome (bacteria in your gut) and its relation to health and disease.

A new study by Jacka et al [1] suggests that intervention by a dietician to help improve the diets of people suffering from depression can help to improve their symptoms.

This is an open access study and you can read/download it here.

Methods

This is described as a single blind randomised control trial (RCT).

Participants were recruited using a variety of methods including advertising on flyers and in social media (pg. 3) which stated:

‘We are trialling the effect of an educational and counselling program focusing on diet that may help improve the symptoms of depression’.

There were a number of inclusion criteria which you can read in the paper on page 3.

These included that participants were over 18, qualified for having major depression (using the MADRS and DSM IV criteria), and had a low score on a dietary rating scale.

After exclusions the final sample included 67 participants.

This was split into two groups an intervention group and a control group which were randomised via computer. Both groups received dietary and psychological assessments.

Once deemed to be eligible, participants completed a 7-day food diary and the Cancer Council of Victoria food frequency questionnaire, in the week leading up to baseline assessment. Participants attended a local pathology clinic to provide fasting blood samples before undertaking baseline assessment and randomisation.

The intervention group received sessions with a dietician (seven sessions of 60 minutes each). The control group received "social support" called a "befriending" protocol of equal duration and frequency:

Befriending consists of trained personnel discussing neutral topics of interest to the participant, such as sport, news or music, or in cases where participants found the conversation difficult, engaging in alternate activities such as cards or board games, with the intention of keeping the participant engaged and positive. This is done without engaging in techniques specifically used in the major models of psychotherapy.

This makes sense - you want the control to replicate the intervention as much as possible but without introducing any alternative factors which might themselves be treating depression (e.g. psychotherapy) and hence diluting the results.

The total length of the interventions was 12 weeks and participants were re-assessed on completion.

Results

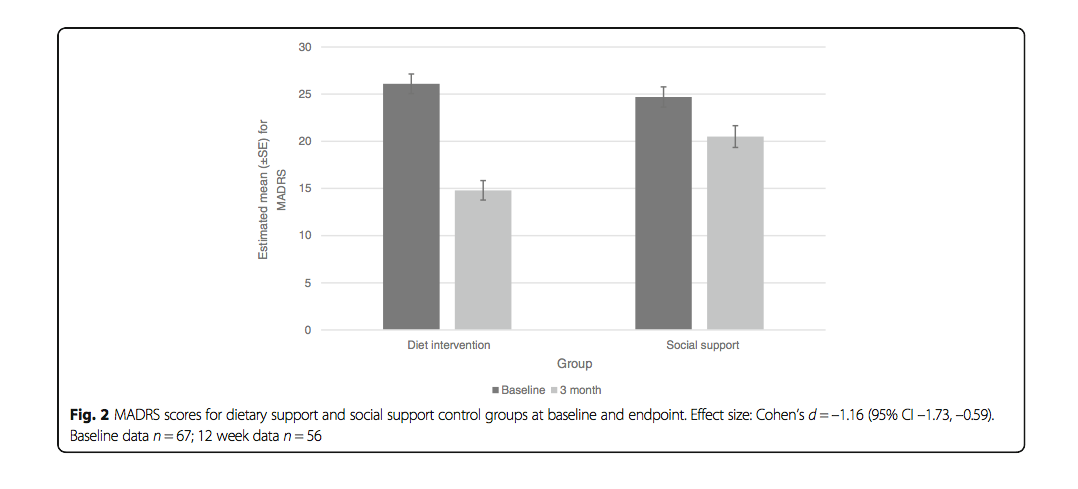

The main results are summarised very well by Figure 2 (see below).

If we look at the graph we can see that there is a larger proportional decrease in MADRS scores for the intervention group (left columns) versus the control (social support) group.

As the authors state:

"The dietary support group demonstrated significantly greater improvement in MADRS scores between baseline and 12 weeks than the social support control group."

There were dropouts before completion of the 12 week interventions (roughly 16%). It is of interest that the dropout rate was greater in the control group:

"There were significantly more completers in the dietary support group (93.9%, n = 31) than the social support control group (73.5%, n = 25)."

Some further secondary outcomes such as how many patients were considered to be in a state of remission from depression were also considered and showed favourable results for the dietary intervention:

"At 12 weeks, 32.3% (n = 10) of the dietary support group and 8.0% (n = 2) of the social support control group achieved remission criteria of a score less than 10 on the MADRS."

There were also some improvements on some secondary rating scales that were used:

"Concordant with the findings for the MADRS, the dietary support group demonstrated significantly greater improvement from baseline to 12 weeks than the social support control group on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)-depression subscale."

"Similar findings were obtained with the HADS-anxiety subscale."

"These significant differences remained after controlling for sex, education, physical activity, baseline BMI and baseline ModiMedDiet scores."

Finally there were significant dietary improvements measured in the active intervention group - I won't list them here but they are on page 8 of the paper.

Problems

For reasons of space (and so I don't bore everyone to death) I can't cover everything here but I will cover the main things that stood out to me.

We have some of the usual suspects when it comes to these kind of studies.

Blinding

.jpg)

Blinding is obviously difficult in a study of this sort - there is no obvious way of blinding the participants to the treatment they were receiving.

A partial attempt was made by giving them limited information at recruitment but this can be ethically problematic.

Further the people administering the actual treatment itself cannot be blinded either for obvious reasons.

Although this is referred to as a single blind study the blinding referred to was applied to the research staff who made the data collection and the statistician who analysed the results.

I'm not sure if that really counts as true single blinding (which one would assume being applied to those giving or receiving the treatment).

The interesting thing is that the actual definition of single blinding is a matter of debate in medical research. This BMJ article by Altman[2] summarises some of the issues and suggests that the term should not be used.

Sample

As the authors state regarding their sample:

We assessed 166 individuals for eligibility. Of these, 99 were excluded. We thus randomised 67 individuals with MDD to the trial (intervention, n = 33; social support control, n = 34)

The sample size is obviously very small. It is understandable given the nature of the interventions (and cost implications) that a larger sample size would not necessarily be possible.

The exclusion criteria are listed on page 3 and do make sense but as we can see the final sample size shrank down from 166 to 67. That is not the whole story though as there were also some dropouts:

Dropouts

Of these 67 only 83.67% completed the final assessment at 12 weeks:

Fifty-six individuals (83.6%) completed the assessment at the 12-week endpoint.

The problem (as I have discussed many times before)with many such studies is lack of replicability and smaller sample sizes increase the risk of anomalous results being observed.

Drop-outs are always likely but they can further skew results and the effect is amplified by having smaller sample sizes.

What if there were certain characteristics of the dropout group that made them resistant to treatment (or alternatively more amenable)? Either way it can skew the results.

Dietary assessment

Dietary assessment involved use of food diaries and interviews.

I have previously talked about how there are questions as to how accurate such methods can be at assessing what people actually eat.

It is easy for people to forget certain things or leave out others which they think might show them in a bad light - particularly in an interview situation.

Other Confounding Factors

.jpg)

Another factor to consider is the interaction of these interventions with other things - for example medication and other psychological interventions.

If we look at Table 1 (page 7 of the study) we can see that 68.7% of the participants were on medication and 44.8% were receiving psychological therapy at baseline.

This can potentially make it hard to be sure how much of the effect we are seeing is due to the actual intervention we are testing here (the dietary support) versus the effects of these other treatments.

It should also be noted that 71.6% of participants were female.

This kind of gender imbalance can also change the applicability of results.

Food Cost

.jpg)

Obviously one could consider that sending patients to see a dietician is expensive. One other factor that I thought of and is briefly discussed is the cost of the healthier diet (versus their old diet for the patient):

Whilst there are many data to suggest that eating a more healthful diet is more expensive than a less healthful diet [45], our detailed modelling of the costs of 20 of the SMILES participants’ baseline diets compared to the costs of the diet we advocated showed that our strategy can be affordable [46]. Indeed, we estimated that participants spent an average of AU$138 per week on food and beverages for personal consumption at baseline, whilst the costs per person per week for the diet we recommended was AU$112 per week, with both estimations based on mid-range product costs.

I think "affordable" depends on the situation of the patient in question.

Someone who is barely able to make ends meet might not be able to afford the extra 23% cost.

It would be interesting to know if this particular factor resulted in some people being unable to adhere to the diet as much as they would have liked.

Conclusion

These results are certainly interesting. They fit with what we would expect BUT we also need to be cautious.

When results fit with our prior expectations, it increases the temptation to give them more weight.

We need to consider these results in the context of the study. The sample size is small and there are other factors which may skew the results.

I know I say this very often, but we need more research to see if these results can be replicated - ideally in larger sample sizes but failing that in multiple small studies.

Obviously there is no harm in improving people's diets but the particular intervention here via a dietician is likely to be quite expensive and time consuming.

Money and resources for medical care tend to be limited in the real world.

Public health interventions often come down to choosing between a multitude of different treatments based on the relative cost:benefit ratio.

We will need more research before we can make an informed decision in this case.

References

Jacka, Felice N., Adrienne O’Neil, Rachelle Opie, Catherine Itsiopoulos, Sue Cotton, Mohammedreza Mohebbi, David Castle, et al. 2017. “A Randomised Controlled Trial of Dietary Improvement for Adults with Major Depression (the ‘SMILES’ Trial).” BMC Medicine 15 (1): 23.

Altman, Douglas G. 2005. “What Is a Single Blind Trial?” British Medical Journal, no. 331 (July): 1.

Thank you for reading

.jpg)