College football season kicked off last week, and with it comes another year of excitement, big plays, tailgating, excited fans, and highlight reel moments. I am a big fan of college football. I enjoy seeing the game played from a strategic standpoint. I like to analyze and criticize play calls, penalties, and any other decisions the players make during the game. I love watching games in person and on television, especially the teams of my undergraduate and graduate institutions.

Million Dollar Locker Rooms

I subscribe to the Wall Street Journal. I read as much as I can of each day’s edition because I believe it provides a good summary of what is going on in the world, especially the business and finance side of things. The weekend edition of the paper always has a featured article, The Saturday Essay, which varies in subject each week, but on August 18, the topic of the article caught my attention. In Stop Giving College Athletes Million-Dollar Locker Rooms. Start Paying Them, Jason Gay presents an interesting view of college athletics, specifically in terms of finances. Clearly, the title advocates for paying student athletes- a subject which has been a source of controversy over the past few years.

Gay’s immediate concern is over the amounts of money that colleges spend on amenities for its athletes, and that such spending is a substitute for paying players. Such examples are the recent upgrade to the locker rooms at the University of Texas at Austin, Texas Tech, and the University of Oregon. It also begs the question, “How does this spending relate to the university’s goal of higher education?” Gay writes,

As with billion-dollar TV deals and megabucks coaching contracts, these luxury athletic facilities signal something fundamentally askew about the economy of big-time college athletics. Professionalization has almost totally arrived: The perks for college teams can be more sumptuous than the ones for pro clubs, and salaries for top college coaches rival those found in the NFL and NBA. But schools remain resistant to writing a check for the one group actually doing the work out on the field: the players.

Many times when this issue is brought to a public forum, opponents are quick to point out that players receive full ride scholarships. Gay also addresses this issue:

But in an era in which networks pay close to $1 billion a year to televise March Madness, college football is expanding into lucrative playoffs, and coaches with shoe deals scoot through the clouds in private jets, the notion of scholarships as fair trade starts to feel quaint.

Gay cites many other issues with the system. Often if players speak out on this issue, the facilities mentioned above are used as a method of silencing the athletes due to how “pampered” they are. Many athletes have to balance their sport and schoolwork- a task that can consume more time in a week than most people spend on their day jobs.

Jason Gay does a great job of bringing out the main points of the issue, but I decided to search around to try to find more information about the subject.

The NCAA

The NCAA logo is a trademark of the National Collegiate Athletic Association

First, it was over to the NCAA’s website. The National Collegiate Athletic Association describes itself as “a member-led organization dedicated to the well-being and lifelong success of college athletes.” The NCAA is at the center of the debate about college athletics, as it controls the media rights for the largest college sports, football and basketball. In the 2015-2016 season, the NCAA took in almost $1 billion from the Division I Men’s Basketball Championship alone. Of this money, around 60% of it goes back to universities in the form of scholarships, student assistance funds, basketball rewards, and other various funds. The rest goes toward other various expenses, the most interesting is the $150 million that goes toward “Other Association-Wide Expenses” and “General and Administrative Expenses.” The NCAA also has a distribution schedule for its 2017 fiscal year posted on its website, but I won’t get bogged down in the numbers.

The NCAA, while claiming to promote the well-being of student athletes, can often be draconian in the enforcement of its rules for said athletes. For example, let’s consider some of the rules violations that the University of Alabama reported to the NCAA in 2016 (via AL.com):

- A football player sold school issued equipment and participation rewards for $820

- Nick Saban, the head coach, was cited for a violation after accidentally dialing the number of a high school recruit instead of a coach.

- A recruiter was allowed to be present during an off-campus meeting

- A men’s basketball team player participated in a practice before signing an NCAA drug test consent form

- A gymnastics team recruit’s father took a picture with a former Alabama football player while on an unofficial visit to the university.

- The men’s track team paid for five family members of a recruit when the rules only allow four

Again, these violations were required to be reported to the NCAA. Some of them resulted in suspensions, but others seem trivial. A few of them, such as the player selling merchandise, could be avoided by paying the players or allowing the players to negotiate fair prices for merchandise. One opinion piece in the Washington Examiner claims:

These rules keep at least the reported prices for athletes' services below prices that schools and athletes otherwise would freely negotiate. Like other regimes that control prices, these rules have produced a black market that facilitates payment of undisclosed and illicit higher prices. Eliminating these payment limits would end the corruption associated with incentives and compensation. No more under-the-table payments. No more jobs and other benefits for undeserving family and friends…

Looking Deeper

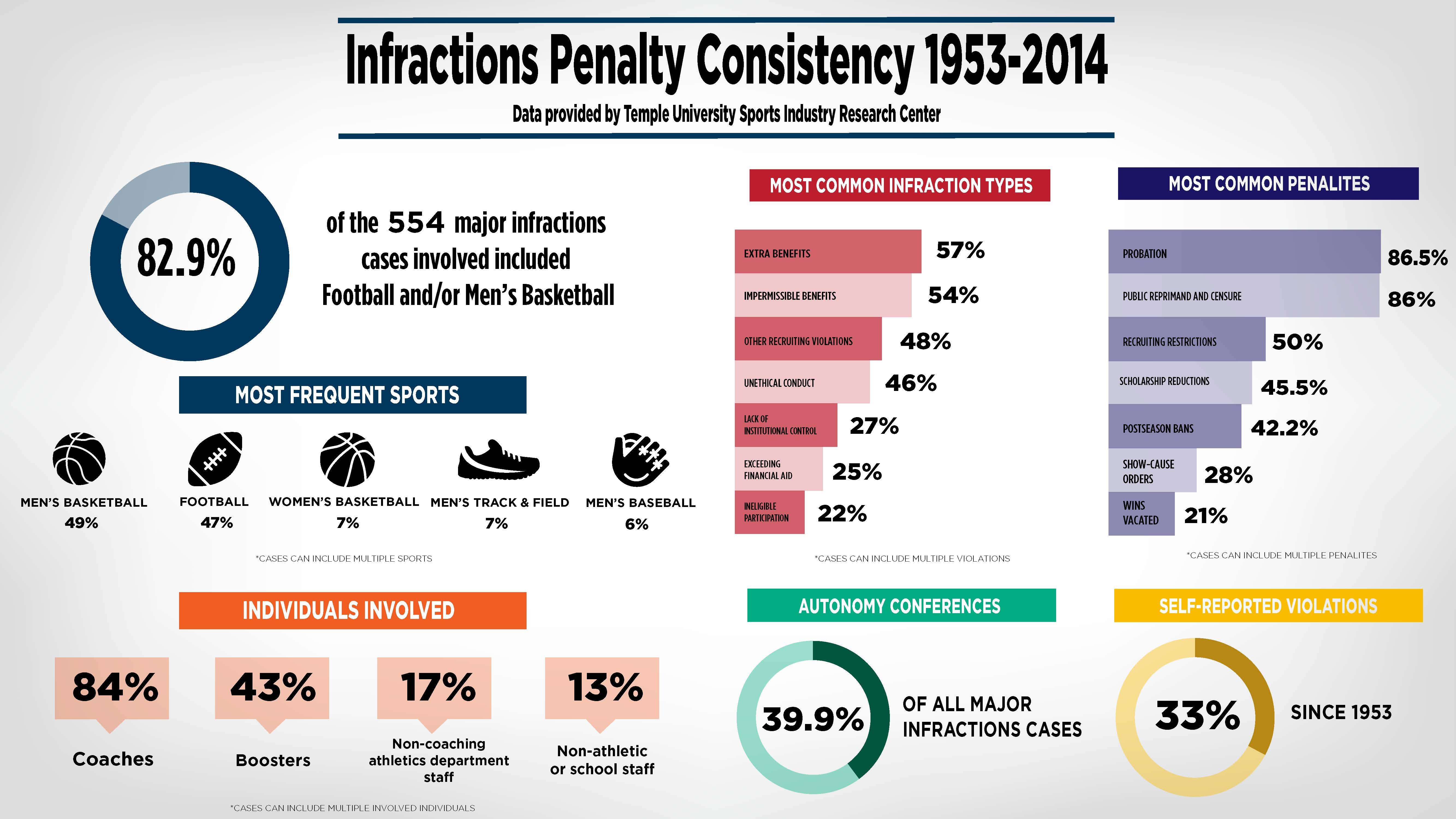

When it comes to rules violations, I know I’ve seen these news items pop up every now and then, but being a scientist, I was curious about hard data on these issues. I discovered a 2016 report by the Sport Industry Research Center at Temple University, which analyzed all major NCAA rules violations from 1953 to 2014. The results are summarized in this infographic obtained via Inside Higher Ed:

The findings are fascinating, but there’s one statistic that blew me away:

Of the 554 total Division I violations, 82.9% involved Football or Men’s Basketball

The sports which are the most lucrative and involve the highest amounts of spending have the most violations. Certainly correlation does not imply causation, but this deserves a closer look. Consider these findings from the same study:

- 56% of cases involved “Recruiting Inducements,” which are defined as “Financial aid or other benefits provided to prospective student-athletes other than as expressly permitted by NCAA regulations.”

- 54% of cases involved some type of “Impermissible Benefit.”

- 25% of cases involved “Exceeding Financial Aid”

Note that each case may have more than one possible infraction type

Developing a system where the players could directly benefit from the revenues gained via college athletics, both by the NCAA and each individual university could potentially cut the number of rules violations in half.

While academic violations made up only 12% of all infractions, recent revelations have led to investigations into how universities keep their student athletes academically eligible. The current system leads to many lewd and corrupt practices. Universities use many methods to keep their athletes academically eligible, as evidenced by the recent “shadow curriculum” scandal at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where athletes were enrolled in courses that did not exist in order to keep their eligibility. Other scandals have arisen from programs attempting to appease their players, such as the Louisville men’s basketball team’s bout with escorts. With events like this, it may truly be worth evaluating whether the NCAA and the universities actually have the players’ best interests at heart.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Part of the issue with paying college athletes is the actual implementation of the payment system. What would such a system look like? Again, we go to the sciences for a possible answer. In a 2015 study entitled, The Case for Paying College Athletes, Allen Sanderson, a senior lecturer in economics at the University of Chicago, and John Siegfried, professor emeritus of economics at Vanderbilt, present a strong case for the payment of college athletes. They also present an extensive background of the issues, which elaborates on the history of universities operating large-scale commercialized sports programs. The article also points out several other troubling aspects of the finances of college athletics, including how only 16% of Division I schools participating in the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) received more money than they spent on collegiate athletics. Sanderson and Siegfried outline what a free market for college athlete “labor” would look like, and how it would impact universities and the NCAA, ultimately concluding that

“The current arrangements in the labor market for big-time college athletics are inefficient, inequitable, and very likely unsustainable. Yet it is far from obvious how to get from here to a competitive labor market without incurring substantial transition costs. While a truly "competitive free market" is attractive, it is not without risk, especially considering that the output restrictions arising from big-time inter-collegiate sports teams' market power in selling tickets and broadcast rights might have been offsetting the expansive pressures of the low price of labor”

It should also be noted that the Sanderson article presents many interesting arguments based on economic data and academic sources. Among these arguments are that the NCAA has huge monopolistic power over college “student-athletes,” and by classifying them as students first, exempt them from labor law protections. In addition, the NCAA’s treatment of athletes may violate the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. I highly recommend reading the Sanderson paper if you are interested in this subject. (You can access the paper via a free JSTOR account. Unfortunately, Unpaywall does not work for this article)

Conclusions

Many considerations are needed to address this issue, but many college athletes’ experiences will suffer if the system remains the same. If college is truly a place of learning, universities should be doing a better job of setting up their athletes for success in the future. Many of the athletes will not have the chance to move on to play professionally, leaving them to fall back on their college degree. If that degree is based on lies or was not properly obtained, how can the universities then expect those athletes to represent their alma mater well in the work force? The system has issues. Players who are told to “shut up and play” while they are in an athletic program may still be used for the college’s gain many years later. These issues cannot be addressed when colleges and the NCAA seek to silence proponents of paying college athletes. At a time when coaching salaries are increasing to the point where many college basketball and football coaches are their state’s highest paid employees and coaches can get their mortgages paid off by athletic boosters, we should re-evaluate the landscape to see if there is a better way to approach compensation for student athletes while still making college athletics a great part of American culture.

There are many sides to this issue that I have not been able to present in this short article. Please take the time to read other articles and build informed opinions of your own. Here are select sources from my post plus a few extra resources you can use to learn more about this topic:

- The Case For Paying College Athletes- Journal of Economic Perspectives

- Stop Giving College Athletes Million-Dollar Locker Rooms. Start Paying Them- Wall Street Journal

- Is It Time To Start Paying College Athletes? Tubby Smith And Gary Williams Weigh In- Forbes

- The NCAA: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO)- YouTube

- Don’t Just Shut Up and Play- The Players’ Tribune

- NCAA Division I Committee on Infractions: Penalty Consistency- Report by Temple University

- The highest-paid public employee in 39 US states is either a football or men's basketball coach- Business Insider

Thank you for reading. These are my own thoughts, supplemented by articles found across the web from a variety of sources. I would love to hear what you think about this subject, especially those who have been involved directly in college athletics. I'm also interested to hear from people outside of the US, since this is largely an American issue.

This article was made possible by the supportive community of #theUnmentionables. If you're looking for a great place to share your ideas and learn how to create better articles, join our Discord channel today!