“There Must Come a Change…”

Public spaces in cities and towns are peppered with statues and monuments. Public art is one of the ways we acknowledge who we are and what’s important to us. How many hundreds (no, thousands) of statues are there of Washington, Lincoln, founders and generals of various stripes?

Together, these representations comprise a national echo chamber in bronze and marble. Where are the women? Not allegorical, mythological or fictional characters—but real people. When Native Americans are represented, they, too, are straight out of storybooks. People of color? In Philadelphia, the African-American legacy in bronze tends to be in the form of sports heroes installed outside the stadiums. There's an underwhelming bust of Martin Luther King, Jr. on a traffic island in West Philadelphia, but what else?

Public memory is managed. And so it will always be—that’s the nature of the beast. Facts are one thing, but no matter what we want to believe, history and culture are interpretations of selected facts. They are constructs, fabrications arranged in the public imagination, bent to the collective will.

But who are we, and can we even agree on who, what and how to acknowledge and what to celebrate? On May 30, 1934, the All Wars Memorial to Colored Soldiers and Sailors (detail below) was dedicated at a site deep in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park. Originally, the 21-foot-tall monument wasn't permitted on any prominent, public site. It took 60 years to correct the mistake and install the monument prominently on the Parkway in Philadelphia.

Credit: Wikipedia Commons

African-American military figures flank an allegorical Caucasian female holding wreaths of honor. The men are anonymous, generic figures. They may have been the product of empathetic intentions, but they remain abstract—nowhere as culturally engaging as real historical figures.

Credits: Wikimedia Commons and the author

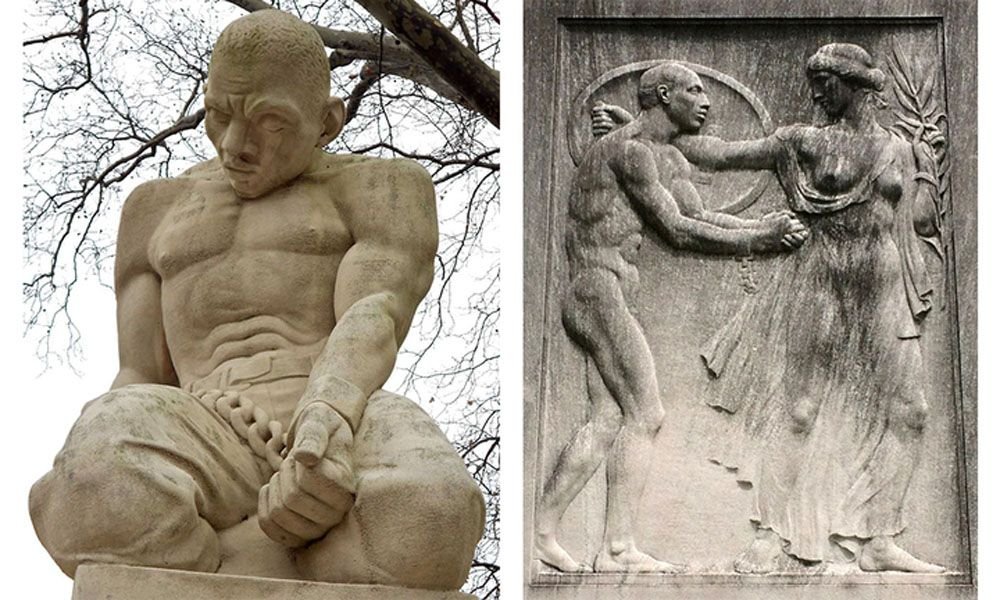

Still more abstract and anonymous are statues representing the enslaved. Two remarkable examples are illustrated above. At left is The Slave, by Helene Sardeau in 1940, at the Ellen Phillips Samuel Memorial on Kelly Drive. On the right is a panel from the Pastorius Monument in Vernon Park by Albert Jaegers commissioned in 1917. It commemorates “The Protest of the Germans of Germantown Against Slavery on February 18, 1688.” Both are powerful, but also curiously patronizing compared with the powerful and actual historical figure of Bussa, an enslaved man who led 400 men and women in a revolt in Barbados more than 200 years ago. That's in Bridgetown, Barbados.

Credit: wanderant.com

So where's the American tribute to real people who made real history in the name of freedom? In a few weeks, Philadelphia will dedicate a larger-than-life monument to an actual African-American hero whose public moment has finally arrived, nearly 150 years after his assassination on election day in October 1871.

Credit: The Philadelphia Tribune

Octavius V. Catto will be the first figure installed on the sidewalk of Philadelphia City Hall since retailer John Wanamaker in 1923. While Catto desegregated streetcars, Wanamaker invented the idea of returnable merchandise. As Catto led the effort guaranteeing the right to vote, Wanamaker opened his second store. Under Wanamaker's name is the word "CITIZEN." Under Catto's his words will be carved in stone: “There Must Come a Change…” The installation is aptly titled “A Quest for Parity.”

It's a beginning.

Credit: Association for Public Art

Looking closer at the faces of the 1934 All Wars Memorial to Colored Soldiers and Sailors, we wonder if these are real men. As it turns out, they may be portraits, not just allegorical figures. At the memorial's relocation ceremony in 1994, Penny Balkin Bach, executive director of the Association for Public Art, heard from a woman in attendance. She looked at the faces and recognized her great-uncle. His name? The names of the other real figures?

Maybe it's not too late to breathe real life into abstract history. And if so, these would be the first historical African-Americans represented in a city known for public art, and, of course, for freedom.

Opinions expressed are my own.