Cinema is fundamentally a diverse and exciting medium. At its core, every movie is simply sound matched with visuals. However, most movies have taken a pretty limited approach - not much different from being "filmed theater". Sure, unlike theater you can replace the stage with actual locations, but strip that away and you're left with theater - a plot and actors pretending to be characters. There are many great plays out there, of course, but cinema could - and should - form its own identity. A new, fresh experience; one which can neither be performed in a theater, nor be put down into words.

There are films that break all cinematic convention, abandoning traditional story logic to offer a more visceral experience; like music does, from the likes of Dziga Vertov to Buster Keaton. And then there's Stanley Kubrick. Kubrick's films retain the storytelling and intellectualism of literature and theater, but marries that with experiential qualities of music and photography. Kubrick's films rely not only on story, but consistently innovate on the form of cinema. Ultimately, editing remains the only unique form to the medium of cinema, but Kubrick showed us how a blend of known ingredients could indeed be mixed into something original and innovative.

A truly independent filmmaker

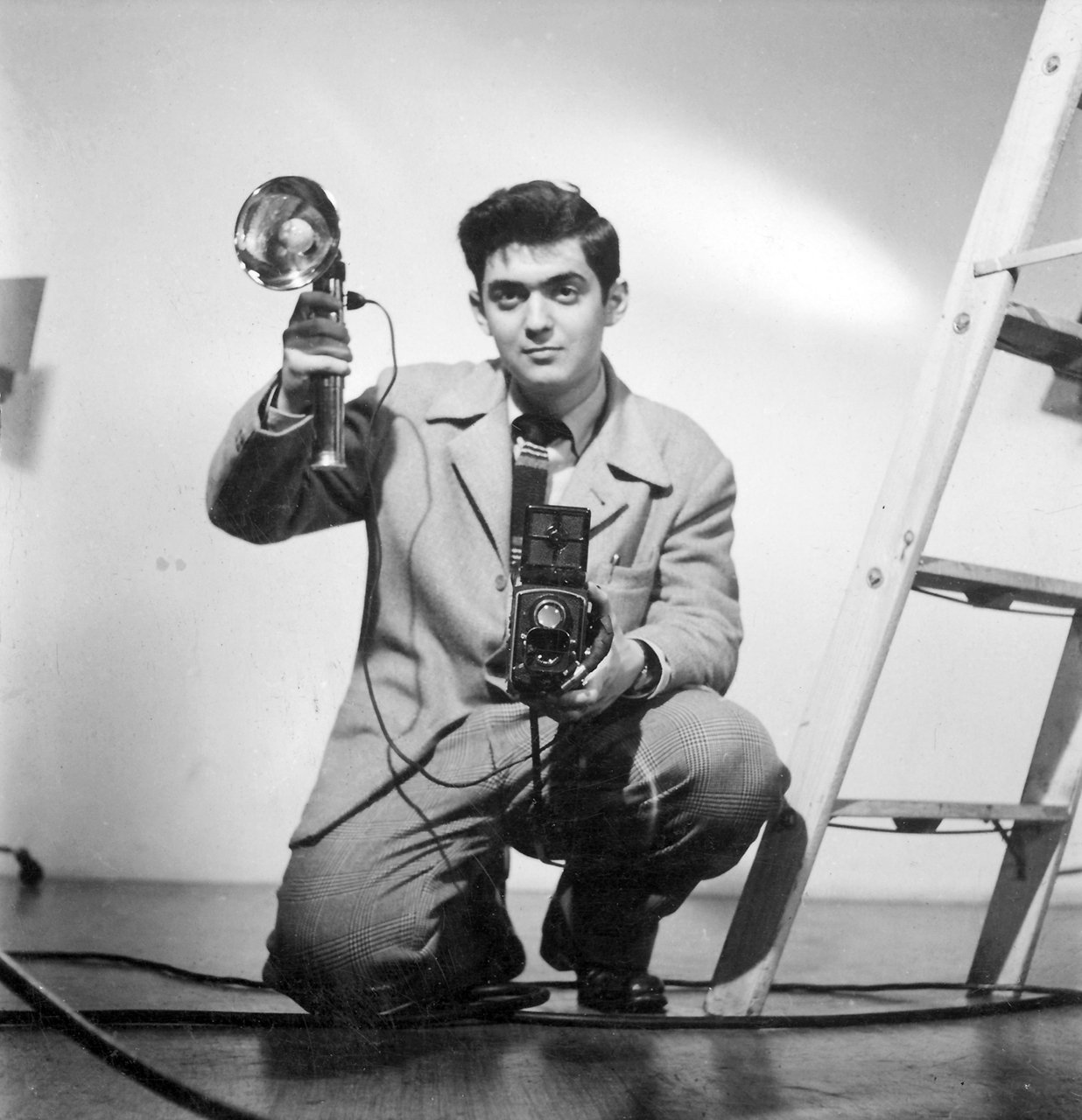

Stanley was the stereotypical teenage rebel. Bored of school, he developed up a penchant for photography. A serious hobby soon turned into a profession with Look magazine. At the time, a vast majority of directors came to film through literature and theater. A photographer-turned-filmmaker was rarely heard of.

An admirer of many arts, Stanley took a great liking to cinema. Seeing the deluge of crappy films being churned out of Hollywood, he asked himself - how hard can it be? Such was his confidence, or even arrogance, that he remarked, "I don't know a goddamn thing about movies, but I know I can make a better film than that." Already an expert photographer, surely all it required was hiring soundmen and actors.

He was right, but alas, just barely. Fear and Desire turned out to be a pretty messy film, though still refreshing relative to the vast majority of films at the time. Kubrick's sense of space - an instinctive grasp on exhibiting a 3D world onto a 2D frame - shined through from the very beginning.

Fear and Desire was not his first work. Indeed, he shot two short documentary films before - Day of the Fight and Flying Padre. Day of the Fight is particularly well shot by Kubrick himself.

While his first fiction attempt - Fear and Desire - was ultimately a failure (one that Kubrick reportedly tried to destroy every print of), Killer's Kiss was a far superior film. It was his make or break attempt - he took full control, producing, editing, shooting and directing it himself. Still suffering from some dodgy writing, it featured some innovative formal techniques which immersed the audience in a dreaded vision of NYC. Already an innovator on form, Kubrick sought out to improve his storytelling credentials.

The studio years

Which he did, admirably. The Killing combined some spectacular editing and photography, this time combined with a smart screenplay. A clever narrative structure co-ordinated with the documentary style filmmaking made for a tense, thrilling film, the first of Kubrick's great films. Full credit to James B. Harris for seeing potential and giving a 28 year old newbie carte blanche. While these films may have lost money at the box office, revenue keeps pouring in to this very day. A lesson for every film financier and producer, indeed. As they say, film is forever.

Despite the failure of The Killing at the box office, Harris kept his promise, producing Paths of Glory - Stanley's first film made on a studio budget with a movie star. Barely a decade after World War II, war films were a dime a dozen at the time, but there was nothing like Paths of Glory.

Completely ignoring the usual nationalist sentiments or "war is evil" themes, Paths of Glory instead examined the minutiae and bureaucracy of a military organisation. A special mention for the incredible trench sequences - those were at least half a century ahead of its time. Later inspiring Spielberg, and subsequently the horrible shakycam fad.

Now a highly sought after young director, he nevertheless took his time, waiting for the right offer. That came from Marlon Brando himself. However, things didn't end well. Amidst multiple creative differences, Kubrick left what would become One Eyed Jacks. Watching that film, it's pretty clear to see why that never worked out...

Thanks to Hollywood politics, Stanley found himself in the thick of a big budget production, taking over Spartacus from the experienced (and now fired) Anthony Mann. Despite being an unusually young director to helm such a big budget production, he stood his ground. Naturally, that led to a rather tumultuous production, with Kirk Douglas in particular annoyed at Kubrick's audacity. In the end, he somehow retained creative control, with a fair few distinctive flourishes, though ultimately constrained by a formulaic script.

To England and Sellers

Lolita will forever remain a missed opportunity, courtesy the censor boards. With New Hollywood and censorship reforms around the corner, it couldn't have been a worse time to make Lolita. Nevertheless, within the confines of censorship, Sellers and Kubrick found a distinct sense of comedy, a different approach to Nabokov's celebrated novel. Lolita was Stanley's first film made in England - there was no going back.

The Sellers-Kubrick collaboration continued with Dr. Strangelove. Initially planned as an adaptation to the quite serious thriller novel Red Alert, Kubrick and screenwriter Peter George's playful imaginations saw a comedy in the most unexpected of places. Indeed, a similar plot but a dourly dramatic film released the same year, Fail Safe, fell flat relative to the impact of Strangelove.

It could be argued Dr. Strangelove is an important milestone in Kubrick's career, and that's a fair assessment. With every new Kubrick film, the craft and form breached new heights. It is with Dr. Strangelove, however, the form reached the absolutely impeccable.

From the grand production design to the quirky costumes, daring camera angles, rapid zooms, unprecedented use of miniatures & related visual effects and disorienting editing, Dr. Strangelove was a masterclass in filmmaking. Not to mention, a quite brilliant script - sharp as a razor - with some outrageous dialogue portrayed through equally insane performances. It remains the best hours of Peter Sellers and George C. Scott.

It also began Kubrick's obsession with having a second, deeper narrative layer running throughout the film. I'm convinced these were conceived of as a playful way to engage with the audience, but of course, critics and students alike have written thousands of essays on the hidden meanings of Kubrick's films. Dr. Strangelove had the coolest second narrative though - a film that appears completely different and even more hilarious from a sexual perspective. It all starts with the title sequence!

Dr. Strangelove lays out clearly what makes Kubrick's films so special -

- A totally whacky sense of humour.

- A complete focus on wrapping the audience in an audiovisual experience, often at the detriment of traditional storytelling.

- Unrestrained imagination - there's no boundaries here. Need not pander to realism.

- Performances that really are - "performances" - not just actors trying to pretend to be real human beings.

- Grand, broad strokes - subtlety does not apply.

- Impeccable craft, exploiting form to enhance storytelling.

- A depth in narrative - there's different themes playing out simultaneously. It's deep enough that it never overpowers the sensory experience.

- Above all, a completely different, pioneering experience every time.

Coming up in Part II - 2001: A Space Odyssey, Napoleon, A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon; Part III - The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, Aryan Papers, AI and Eyes Wide Shut.

References

Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures, directed by Jan Harlan

Stanley Kubrick: The Complete Films by Paul Duncan

The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick by Jerold Abrams

http://www.visual-memory.co.uk/amk/doc/0047.html

http://www.artofthetitle.com/