I’ve been consistently employed (if only part time) since I was 16 years old, when I took a job as an assistant to an Argentinian paparazzo so I could save up money for my first dSLR camera. Every day, after school, I’d sit in his back house and edit photos of celebrities performing completely mundane tasks (Celebrities! They’re Just Like Us!); somehow, this managed to get boring pretty quickly.

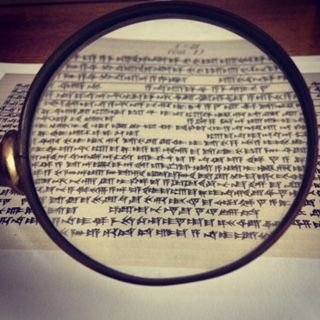

Since then, in no particular order, I’ve been: a host in the dining room at a country club, a computer and cell phone repair technician, an archaeologist, a cashier at a bakery, a party photographer for A-list celebrities, an employee at a vintage clothes store, a teacher at an Ivy League university, a religious school teacher at a synagogue, a graduate student, a show promoter, a viral video buyer, an ancient language decipherer, a freelance writer, a production assistant, and presently, an operations manager at a digital media company (while also tutoring and working part time for a cryptocurrency exchange). I am a master of the side hustle. In summary, I’m a multipotentialite.

Embracing One’s Inner Multipotentialite

At this particularly low point in my life, I watched Emilie Wapnick’s brilliant TED talk about being a multipotentialite, someone who has a broad range of interests and jobs and can thrive in many different careers. Her talk completely reformed my perspective of myself and my attitude toward the meaning of success, and gave me hope that genuinely changed my life. Instead of feeling stifled, uninspired, and lost, I felt free to pursue anything that seemed interesting to me without the fear of being stuck for the rest of my life.

It’s an especially American tendency to mistake the gift of versatility for being directionless. Our culture tells us that success looks like a steady climb up the ladder of a white collar career job—and just one career at that. The ideal American sits on the top rung of the ladder of their One Career earning a 6+ figure salary. Personal interests are merely “hobbies.” We are uniquely obsessed with the idea of the self-made multi-billionaire from humble beginnings as the ideal American (see: Donald Trump’s insistence on that “small loan of a million dollars” narrative). On the other hand, those who forgo the ladder climb to pursue personal interests like art, humanitarianism, or music are viewed as directionless grifters working minimum wage jobs with “meaningless” humanities degrees.

Why Do We Discourage Multipotentialites?

If I have a central thesis here, it’s to say that American culture in particular should embrace, rather than shun or discourage multipotentialites. We pressure (if not outright force) students to pick university majors that are extremely specific even if they’ve expressed little to no interest in those fields, while simultaneously treating liberal arts degrees as frivolous. After thousands of years of liberal arts being the backbone of higher education, humanities fields like philosophy, history, and psychology are being rapidly defunded, while engineering, computer science, and pre-med majors are taking over. If we shun broad educational paths in favor of pure vocational majors and create a world in which humanities degrees are “useless,” we will likely end up with generations in which natural multipotentialites feel dissatisfied, depressed, and intellectually crippled when we could have encouraged and collectively thrived from their versatility and range of ideas.