Part Three-- From the Kinks & Grace Jones to Miles Davis and points in between. This is a particularly interesting part of Ronny Jordan's musical journey.  Click here for part 1

Click here for part 1

Ronny Jordan Interview Part 3

Ronny Jordan -- Mackin' -- Why not listen while you read

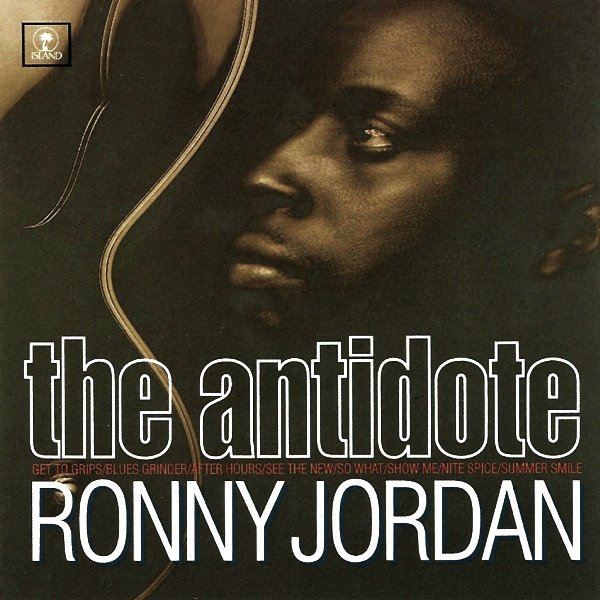

Alan Bryson: You must have been in your late 20s when The Antidote album came out, and it made such a splash. You know Ronny, I used to think of you as an overnight sensation, but that can't be true. (Ronny is laughing) You probably paid some dues, so I was wondering, could you sketch your musical life? Like from your late teen until you landed the record deal with Island Records.

Ronny Jordan: Absolutely, I'm happy to do that. Okay, I left high school in 1979 and I enrolled in college. My dear late mother had passed away in 1976, and I'm the second oldest child in my family. So in '79 the wounds were still fresh, we were mourning our dear late mother, she was only 40 years old when she passed. There were seven of us, so happened was, my oldest brother left home, so I was the eldest child at home. So I went to college for a year, a business studies course, and I passed. It was a general diploma, and I qualified for a national diploma and that was two years, whereas a general diploma was for one year.

So when I was about to do my national diploma my late father decided that I should work. He was made redundant and the rest of my siblings were all at school. I had to work, I had to get a job, so I did, this was back in 1980. By then I had gone to my first recording session, and I loved it. I started harboring dreams of becoming a full time musician. So from '80 to '85 I was working – my last job was for the police in London. Things started to get crazy, because by now I was starting to do a lot more session work. I was burning the candle at both ends, so I knew that at some point I would have to decide if I was going to do music full time, I knew I couldn't keep going the way I was, because I love music and I wanted to make a career out of it – and hopefully someday sign a deal.

So I had been working for the police from 1982 until 1985, and when I would leave that job, I would go and do recording sessions. Anyway, I had a chance to become a cop, and right down the road was the national training center for cadets, and they were ready to send me there because they needed more ethnic minorities. In my office the cops would come by, and they would stand me up and put their helmets on my head, and their jackets on me, and say, “You look really good in a uniform.” And I thought they were joking until one day the chief superintendent, the highest ranking officer in the whole building, he called me in his office and said, “We're serious, we'd like you to be a policeman.”  All the other black policemen in the office would speak to me privately and encourage me to join, saying it would be good for me. But I wanted to do music, so I had two choices, and in the end I decided to do music. I left in August of 1985, and the superintendent told me, “Look, if it doesn't work out for you, come back and be a cop.” I told him I would. (laughing) This was 28 years ago.

All the other black policemen in the office would speak to me privately and encourage me to join, saying it would be good for me. But I wanted to do music, so I had two choices, and in the end I decided to do music. I left in August of 1985, and the superintendent told me, “Look, if it doesn't work out for you, come back and be a cop.” I told him I would. (laughing) This was 28 years ago.

So I went into full time and became a pro in 1985. What helped me was a session I did with a great guitar player, it's sad because he's no longer with us. Are you familiar with Grace Jones?

Alan Bryson: Yes I remember Grace Jones – she was like 6 feet something and had that squared off haircut.

Ronny Jordan: She had a big hit record, Slave to the Rhythm and he played on that. He was the first serious pro I ever met, his name was JJ Belle. JJ performed for a lot of groups, you've heard his playing because he was everywhere. He inspired me because he told me I'd be a better guitarist if I went full time because I could practice, and I would improve a lot more. I loved that, and besides, I wanted to travel the world. So I went pro, much to the annoyance of my late father. (Laughing)

I mean we always got along really well, I love and respect him, it's been eleven years since he passed away. That was just the one time we didn't agree. Well anyway, I went pro, and work was slow. But prior to that, going back to 1981, back then I was at a club, I wasn't inside, but outside you could hear the music coming out. So I would talk to the bouncers, but what was amazing to me was when I heard this hip hop beat. This was about 2am or 3am in the morning, so I hear this hip hop beat, and I hear some jazz guitar, but you could tell it wasn't on the same record, it was the DJ. He was spinning both sounds together, and it sounded amazing, just amazing. He made it fit, you know it might have been some Kenny Burrell or Grant Green. It wasn't Wes Montgomery and it wasn't George Benson, it was more like Kenny or Grant, and it was really hip. That's when the idea came to me, and I realized this is where I should go (musically.)

So in the early '80s I was in a lot of bands and doing gospel projects, because I was still in the church. But I was in some other bands as well. The whole jazz hip hop thing was a side thing for me back then. So being in all these bands, there was a lot of politics, and you know me, I'm all about the music, I'm not about the politics. So anyway, what happened was right about 1989 or 1990 I left the band thing and started to develop this hip hop jazz thing.

What I realized is that I would need to dumb it down if this was going to make it on the radio – I'd have to lighten it a bit. So that is when The Antidote was born.

Alan Bryson: How did you get the deal, did you have it worked out in your mind what you needed to do?

Ronny Jordan: I'd sent demos to all the labels in London and they all turned me down, basically saying what you have here is nice, but there's no market for it. So what happened was, I was doing a gig with a singer, and while I was backstage I was talking to this guy from Island Records and we struck up a very interesting conversation and he never forgot me, and at the time he was working for the studio. So a few years went by, and back then the straight ahead jazz thing had sort of made a comeback, so what I did was to get some friends and we went into the studio to do some straight ahead stuff.

So I sent that to the label. I called them and it was the same guy I'd talked to before, because when I said my name he said, “Hey I know you! We talked backstage.” And what happened was that he'd moved over to A&R and I didn't know that. He said what I had sent was nice, but they'd heard it all before, and he asked if I could give them something unique. So I told them, that I had this other project I was working on and you might want to hear it. They said, “Well send it.” So I sent him an instrumental version of Get to Grips. He loved it, he said, “This is what I'm talkin' about!” So give me a few more like that and we can do a deal.

I had this idea for So What and I did it at a friend's house, and I sent it to the guy, and when he heard it, he called me right away, and he told me: “Can you get here today!” So I got on the bus and I went there, and he told, look, “I want to sign you.” And before I knew it, the legal attorney for the label was in the room, and they took my details down and it just went from there. This was early 1991, and I signed the deal in July of 1991, so it took like six months. So in August I recorded The Antidote and in November it was finished. They loved So What so much they said, “Look, this is going to be the single. That's the hottest thing we've heard in a long time.”

Miles Davis performs "So What"

Miles Davis performs "So What"

What's ironic, I don't know if you've heard this, but we were thinking of getting Miles Davis to do the video. But we were told he wasn't feeling well.

Alan Bryson: Didn't he die around that time?

Ronny Jordan: He died the night I finished it! Do you remember the band from the 60s The Kinks?

Alan Bryson: Oh sure.

Ronny Jordan: They had a recording studio, I found it on Facebook, it's closed.

Alan Bryson: Funny coincidence, I think Derek Trucks bought the board and some stuff from that studio.

Ronny Jordan: Yeah! Well that's where we finished So What and Ray Davies he popped his head in the studio and said it's going to be a hit. So I met Ray, and I grew up listening to the guy, and suddenly Ray Davies is before me, and he was really commending the track. He said, “Oh I love this, it's really funky.”

So anyway, I went home, I was living with my ex girlfriend. It was really late, and I put my headphones on and I played So What through my system and it sounded great. And just after I played it, I switched on the TV and this was 1991 and they were talking about the first Gulf War and there was a picture of Saddam Hussein and suddenly it changed to Miles Davis. And I thought, oh my God, and I knew right away what it was going to be because you don't see Miles on the news. And of newscaster announced Miles had passed away, and I was startled. So out of respect I didn't want them to release the record. And the label was like, “Are you kidding? We're going to release it!” And back then they had DAT tape, and one of the A&R guys went to a club and just played the DAT tape, and the place went crazy. This was in London, and they were like, “WHO is that!”

Ronny Jordan performing an extended version So What live at New Morning Paris

Hope you stop by tomorrow to follow Ronny's journey

Photos (except Antidote album cover) are Vimeo screen captures with effects by @roused