I wasn’t searching for the meaning of life when I found it. It started, as so many things do with me, as an idea, quickly exteriorized in the form of a diary entry.

It was a theory about why people get depressed, and, like a secondary character in a novel who begins to demand ever greater attention from its author, and ultimately succeeds in taking over the stage, within a couple years this idea grew to encompass and explain the whole of life.

At age 25, I had the most comprehensive theory about the meaning of life that any human had ever devised. That was, in no small part, due to the fact that there had never been any real theories about the meaning of life! Yes, the question “What is the meaning of life?” might seem like a familiar and popular one, and so surely there must've been people who had attempted to answer it in the past? Well, unlike much more tractable questions—child's-play issues like whether God exists, or whether we have free will—all the books that have ever been written about the meaning of life can fill one shelf of one very small bookcase. And most of them, when you've read them, will leave you wondering whether they have said anything at all about the question at hand. It’s often a bait-and-switch, books proffering to be about the meaning of life ending up being guides to happiness, stories about survival in concentration camps (I’m looking at you, Frankl!), or essays about ethics.

My book is no such thing.

"Fewer books have been written on the meaning of life than on any other philosophical topic."* - MOL p. 16

* This statement is meant to reversely mirror the oft-heard claim that more books have been written on free will than on any other philosophical topic. Oft-heard, but I’ve no idea who said it. Or whether it’s true.

I self-published it in 2011, left it unpromoted because I’m not good at that sort of thing, and then moved on to other things. It’s really just a self-curated compilation of my most important diary entries on the subject of the meaning of life. Hopefully, it will find some new life here on steemit, where I will try to explain its main insights in a simpler language, and hopefully with pictures.

So, let us begin!

Is it possible to be a nihilist?

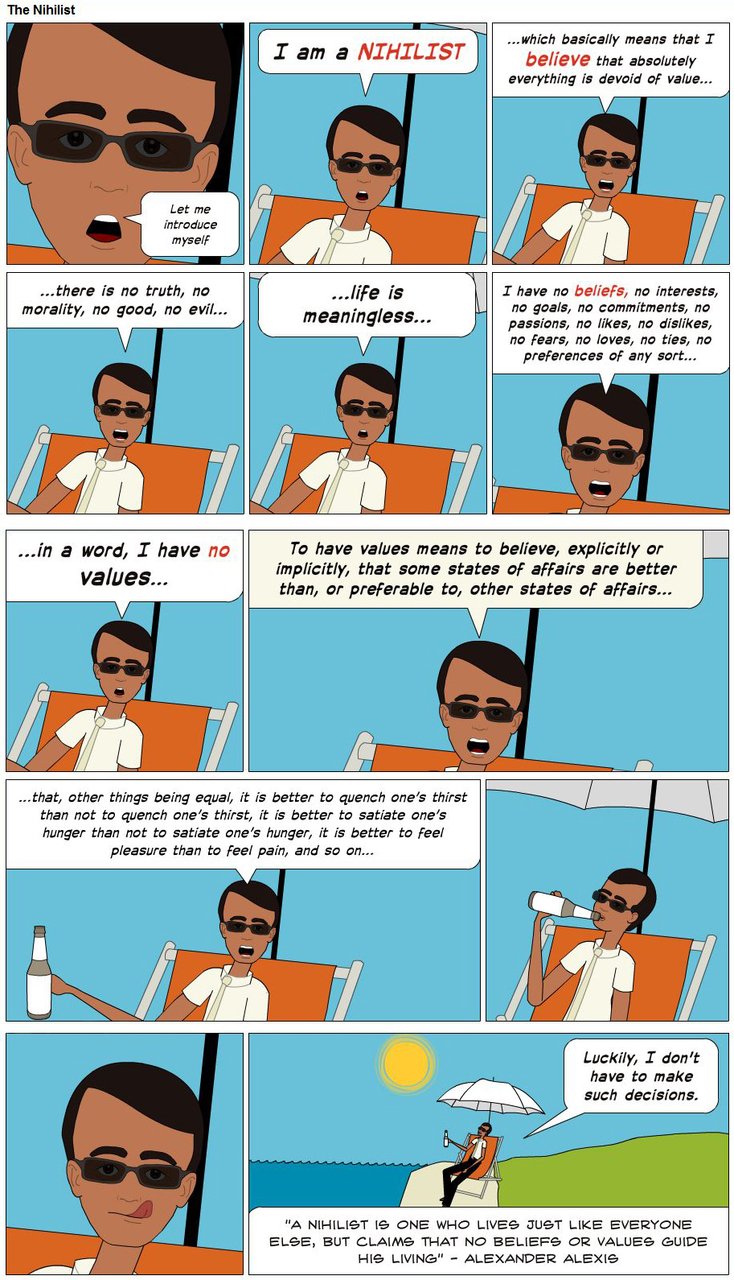

Before embarking on our journey toward positive theories about the meaning of life, we have to dispatch the enemy at the front gate—the person who outright denies there is any meaning in life—the nihilist. The way I approach this task is to claim that no such person can actually exist. Yes: despite what you’ve heard, there are no nihilists!

"Here is a quick definition of nihilism: Nihilism is the noun-equivalent of a negation, such as “anti-.” Thus moral nihilism for example is the belief that morality does not really exist, that it is not an objective feature of the world, that it is pure invention. One can be a nihilist about anything. If a person thinks life is meaningless, then this person is a nihilist regarding life’s meaning. One can also be a nihilist about everything at once. This kind of person would believe that absolutely everything is devoid of value." - MOL p. 24

In the book’s first chapter, I mostly try to prove A:

A: It is impossible for a sentient being to lack values.

To me, this sentence is synonymous with B:

B: It is impossible for a sentient being to be a nihilist.

Proving A therefore establishes B. Whether I am right in taking this approach to defeating nihilism is something the educated reader will have to decide for himself.

Most of the arguments in the section of the book that shares the same title as this article, can be more or less grouped under the following headings:

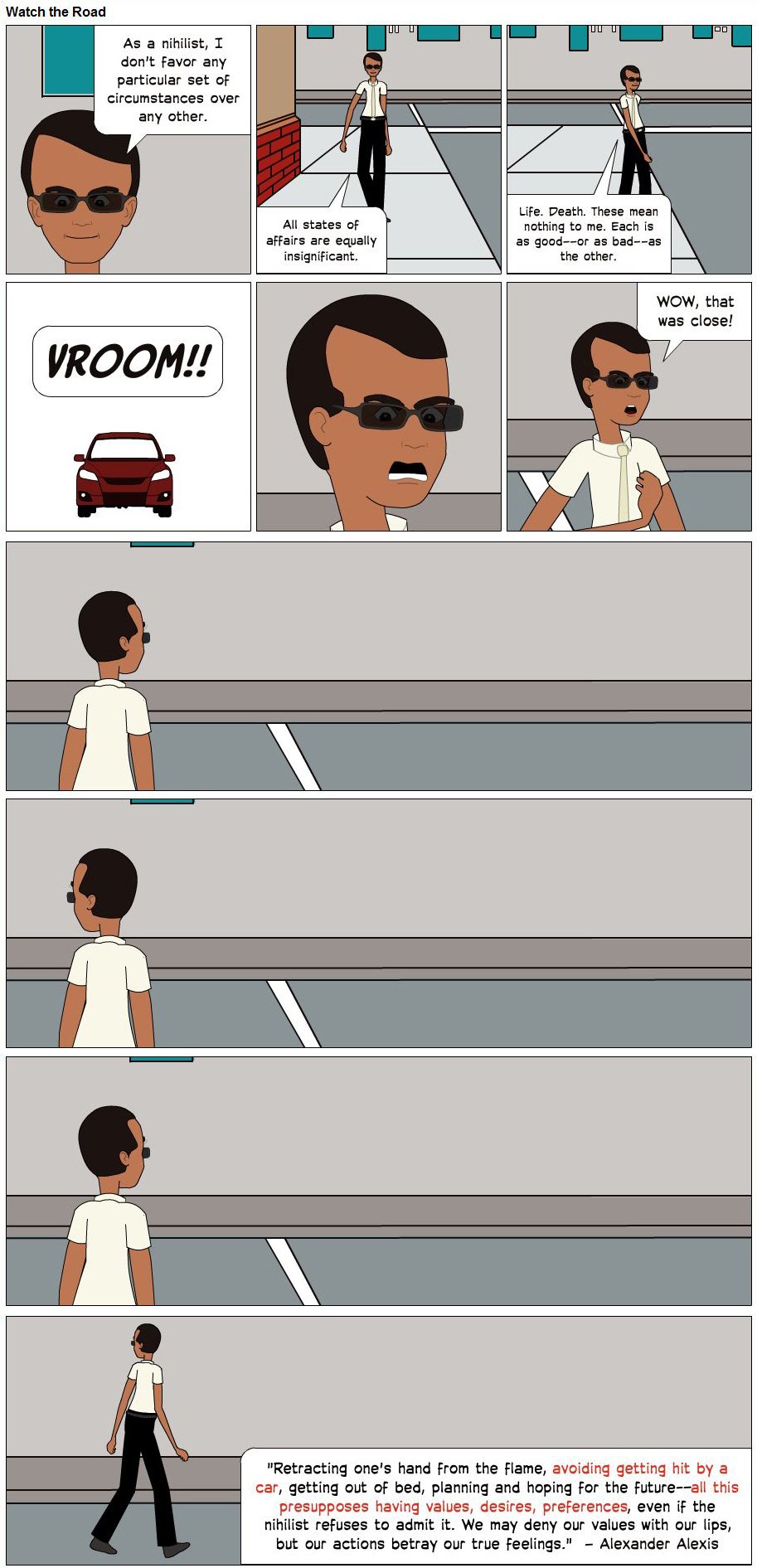

- Actions betray [I use “betray” here in the sense of “unintentionally reveal”] values. A being cannot act unless it has values, because in order to act a being must make choices, and these choices must be guided by preferences—preferences being another word for values.

- Decisions betray values. Without preferences to guide its decision, a being would be unable to make a decision.

- Life betrays values. A being cannot live unless it has values, because in order to live a being must eat, drink, breathe, etc., and a being who has no values will not value eating, drinking, and breathing, and will therefore lack any reason to do these things.

- Desire betrays values. Without desire there can be no motivation to do anything. Desire is a species of value.

- Judgment betrays values. The judgment “roses are more beautiful than mushrooms” means there is something in a rose that you value more than whatever there is in a mushroom.

- Perception betrays values. A lion will view a beautiful human female as a potential meal, whereas a male human will view her as a potential mate. The lion values the female only as a potential meal, and this determines its perception of her. In general, an object cannot be perceived unless it is perceived as possessing some value. And when I say “value,” I include negative valuations. In this sense, a tiger is “valuable” because it is dangerous, and water is just as valuable because it is thirst-quenching.

- Thinking betrays values. In order for an object to feature in our thoughts, we must conceive it as something that is of some value or disvalue to us. We cannot conceive of objects that are of no value to us.

- Fear betrays values. For example, we fear pain because we value its absence. A person who values nothing will fear nothing.

- Hope betrays values. Hoping for X means that X is a valued state of affairs.

- Emotion betrays values. A person who is capable of being moved by, say, a painting, is a person who values art.

All the above can be summed up in the statement “sentience [or consciousness] presupposes values.”

The book goes on about each of these numbered points in more detail, but I believe the educated reader will have gotten the gist by now, so that this article can safely be drawn to a close.

In Part 2 of this series I will briefly touch on the question of whether death makes life meaningless.

For now, I leave you with this question: Should we take nihilism seriously? What do you think? Reply in the comment section below.