Things and Persons

You’ve probably heard the expression, “Animals are people, too.” It’s a cute expression meant to show respect for animals, but actually being a person has a great deal of significance both morally and legally. Moral rights can be easier to understand because they line up more closely with our common sense views of protecting others from harm. Legal rights don’t always work the way we might like or expect them to. But it’s important to understand how they work because in order for nonhuman animals to have meaningful protection, they have to have legal rights. And only legal persons can have rights.

In law, an entity is either a person or a thing. Domesticated animals are the property of their owners, and their owners can use them for profit or pleasure, or kill them at their will. There are some anti-cruelty laws that provide some protection, but they don’t protect the rights to life and liberty, and they are weak for animals we don’t consider companion animals. For example, you could go to jail for treating a dog the way pigs are treated. And rats used for animal experiments in the US have no protection at all under the Animal Welfare Act because they are not classified as “animals” in the Act. These differences in treatment are not based on the interests of the animals, but on what humans prefer, or at least tolerate under the law.

Yet legal personhood has been granted to non-sentient entities like corporations. So a corporation has more rights than a pig. Once, to prove a point, a man drove in a carpool lane with only himself in the car and the legal documents for the corporation on the passenger’s seat. When he was pulled over for driving alone in the carpool lane, he produced the documents and said that there was another person in the car with him.

Negative Rights and Positive Rights

At its most basic level, animal rights refers to protecting the most important interests of nonhuman animals, such as the rights

not to be owned as property

not to be harmed

Though there is some disagreement over whether death is a harm, it is widely accepted that the right not to be harmed includes the right not to be killed.

These are negative rights, which are rights that restrain the behavior of others.

Many animal rights advocates believe animals should also have positive rights, which would be duties to do or provide things for animals to help protect their interests. But nobody who advocates rights for nonhuman animals thinks that they should have all the same rights as humans, because animals have different capacities and interests. Pigs and rabbits don’t need driver licenses or public schooling, but they do have an interest in being protected from enslavement and bodily harm.

Animal rights refers to giving the rights to a species that make sense for that species, in order to protect their interests.

There is a distinction between moral rights and legal rights, though the line is often blurred when they are discussed. Moral rights usually refer to something that is inherent, either God-given or part of natural law. But philosophers and other defenders of nonhuman animals who don’t believe that there is any divine or natural source for them may discuss moral rights as a useful construct, as a way of guiding how we should act toward nonhuman animals.

When discussing moral rights, those rights exist whether they are respected or not. So we could say that cows, pigs, and chickens have the moral rights not to be owned as property or subjected to bodily harm even though those rights are not enshrined in law or respected in practice.

Only Conscious Beings Can Have Rights

Generally, rights are not considered to apply to all living beings, but only to conscious beings. Rights are about protecting others from harm or providing them with things that will increase their wellbeing. Since only conscious beings can be harmed or have good experiences, only they could have rights.

Consciousness refers to the awareness that is required in order to experience things. The term sentience is more often used in discussing animal rights, because sentience refers to the capacity to have positive or negative experiences. Sentience requires consciousness, but technically an entity could be conscious (aware) but have entirely neutral feelings about everything.

Tom Regan’s Subject-of-a-Life Criterion

The first person to popularize the idea of moral rights was Tom Regan, who in 1983 came up with the subject-of-a-life criterion, which required having certain cognitive capacities, such as the ability to have beliefs and desires and to conceive of the future and form goals. According to Regan, any animal who is a subject-of-a-life has inherent value and therefore moral rights.

For him, the basic right is the right not to be treated merely as a means to an end, which includes not being harmed. He argued that normal mammals one year old or older are subjects-of-a-life, though he acknowledged that there may be many other animals who are as well. His goal was to make a clear case that at least some animals have inherent value and thus moral rights, so he intentionally set the bar pretty high in requiring advanced cognitive abilities.

Other theorists believe that moral rights should be based on sentience alone, since it is only sentience that determines whether a being can be harmed.

Legal Rights

One does not have to believe in moral rights to believe that nonhuman animals should be given legal rights. Legal rights are a human construct. When it comes to both moral and legal rights, there is disagreement about what should be the basis for being a rights holder and what those rights should be.

Political philosopher Robert Garner believes that nonhuman animals should have a right not to suffer because their capacity to suffer is similar to that of humans. He considers their interest in continuing to live to be lesser than that of humans. He focuses his efforts on the humane treatment principle, or protecting animals against unnecessary suffering, because he thinks that is most politically possible. He does not necessarily oppose the property status of animals, though in practice he thinks it may be necessary to end it in order to end the suffering of animals used by humans for such uses as food and clothing. This view has been criticized because the right to not be owned as property – legal personhood – is generally considered the foundation for all other meaningful rights.

Legal Personhood

The concept of legal personhood is one of the most important concepts in animal law. Legal persons cannot be owned and have the basic rights to liberty and freedom from bodily harm. They may have other rights as well, but these are the most important negative rights that most proponents of legal rights for animals argue for.

There is disagreement about what personhood should be based on – sentience or certain cognitive abilities. Lawyer Steven Wise has proposed autonomy as the criterion, because that is what it is for human beings under US law. He is taking a fairly conservative common law approach by basing his case on autonomy since it’s already so well established in US law.

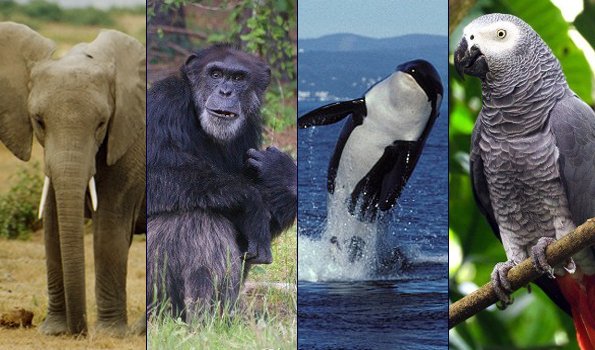

He’s bringing lawsuits to try to get at least one primate in captivity recognized as a legal person by demonstrating that they meet all the criteria humans do for autonomy, which includes not only the capacity to feel but also having beliefs, desires, intentions, and a sense of self. This would include the great apes, cetaceans, and elephants. And likely pigs, dogs, and some birds as well. But he is starting with the animals who are most like humans because that makes it easier to break through the psychological barrier as well as the legal one.

Wise doesn’t necessarily disagree with sentience as a reasonable basis for legal rights, but explains, “the capacity to suffer appears irrelevant to common law judges in their consideration of who is entitled to basic rights. At least practical autonomy appears sufficient… philosophers argue moral rights; judges decide legal rights.”

Wise, among others, believes that breaking the species barrier when it comes to legal rights will be a major step forward even if it does just “redraw the line” between animals considered worthy of rights and those who are not.

Related Post

@stickman/do-non-humans-possess-the-same-inherent-rights-that-humans-do

Further reading

Rights theories: the general approach

Animal Rights Theories

Drawing the Line: Science and the Case for Animal Rights