This is probably my last post in the series Homo homini lupus, and for the rest of them feel free to go through my blog archive - i will not clog this post with links (and you might find a more good stuff) - which covered general thought as musings on issues of morality. This is a bit of conclusion to it, but nothing too final mind you.

I have covered in the past human nature - which binds all of us -, human nurture - the environment in which develops - and free will - how each acts within the bounds of nature and environment. Can this lead something more or less universal?

Although cultures and religions differed widely through human history, when dealing with moral issues you can find an abundance of common threads, just, sadly, not consistently applied. And the whole point of a principle is consistency, otherwise you can change your views depending on how the wind blows.

Principles but- especially the ones which sound good - can often be found in many a culture, and after the but is where people rationalize exceptions. This is were many a problem begins. When we start with rationalization, there might be no end to it. Let’s not go excepting people. Nobles who owned slaves or indentured peasants were screaming about freedom and tyranny and rights when the king came around. I would posit (if this is the word) that if someone admits a right exists for him, he cannot refuse to extend same to others.

The basis of most rationalizations were to consider some humans inferior to others, maybe even less than human. This was the easiest way you could justify treating them like you would not want to be treated yourself. It was a way for the noble to justify oppressing the inferior peasant, while this not being inconsistent with his rights. Peasants and nobles are not the same, they would say, based on absolutely nothing objective or scientific. Same was extended to gender, race, and whatever the hell else was convenient to justify immorality.

You can think of asking a question to a person about himself. How many people would have the same answer? I think if you ask someone “do you agree that someone can just come and kill you with no repercussion”, I think the vast majority would say no, so we can agree the “murder is bad” is universal. So then it should be universally applied to all Homo sapiens, without trying to find nonexistent differences between them.

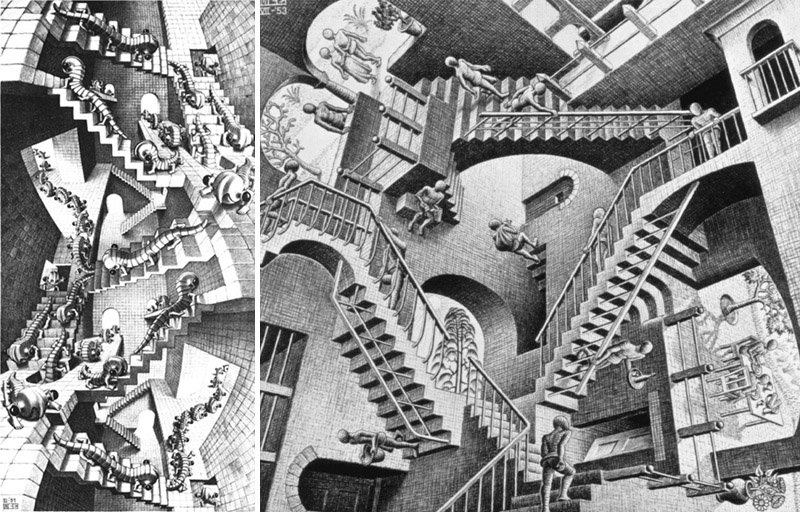

On the topic of moral absolutism versus relativism, I would say that any moral philosophy needs to have axioms, let’s call them the fundamental principles, the paradigm .These are … let’s use the word imperatives, why not, it is a perfectly cromulent word. And these have to be applied universally. No exceptions can be made.

These fundamentals can suffer no significant adjustments, like the axiom of Euclid in geometry or defining that the operator + means that 1 + 1 = 2. If these basics change, you cannot have a coherent system. If we do not like relativism, it would mean that these can be objectively determined. These imperatives would be against murder, rape and other heinous infringements of one’s body. This should be The Law.

Other less imperative moral principles are about day to day life and can be adjusted to circumstances and off course one's own conscience. Is it ok to lie to your parents? Well yes, if the car just hit itself to the tree with no fault of your own, tricky these cars are. Adjustments might be up to a point, because adjusting a principle too much is eerily similar not having one. Excessive subjectivism or relativism leads to not having anything vaguely resembling a coherent model.

You can’t have math, geometry if 1+1 changes value, the formalism should be constant. Well, you can, but everyone would get a maximum grade on the test. And there should be a set of clear and logical steps between axioms and theorems that do not change; higher level should be derived from lower level. There should be some level of consistency, not it’s A when it suits me and B when it doesn't.

When justice was at the whim of a king lord most often there was no justice, or at least it greatly varied based on the lord. While there is a need to be pragmatic about real world politics, one should have some idea about the base principles one stands for, analyze them and make sure they are clear and consistent, as much as possible.

Although it may be too much to say my views are 100% clear objective axioms, human reason can be used to find something as close to objective as possible.

I will leave you with the words of Lewis Carroll, because, well... he uses words prettier than me.

„If a man will go into a library and spend a few days with the Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics he will soon discover the massive unanimity of the practical reason in man. From the Babylonian Hymn to Samos, from the Laws of Manu, the Book of the Dead, the Analects, the Stoics, the Platonists, from Australian aborigines and Redskins, he will collect the same triumphantly monotonous denunciations of oppression, murder, treachery, and falsehood, the same injunctions of kindness to the aged, the young, and the weak, of almsgiving and impartiality and honesty. He may be a little surprised (I certainly was) to find that precepts of mercy are more frequent than precepts of justice; but he will no longer doubt that there is such a thing as the Law of Nature. There are, of course, differences. There is even blindness in particular cultures - just as there are savages who cannot count up to twenty. But the pretence that we are presented with a mere chaos - that no outline of universally accepted value shows through - is simply false and should be contradicted in season and out of season wherever it is met. Far from finding a chaos, we find exactly what we should expect if good is indeed something objective and reason the organ whereby it is apprehended - that is, a substantial agreement with considerable local differences of emphasis and, perhaps, no one code that includes everything.”