Stadiums, designed according to the Roman Colosseum, were built at the end of the 19th century, when workers had won the right to an eight-hour work-day, in order to keep the “working masses” under control during non-work hours. The predominant forms of play, which were to become the cheapest principal spiritual food for workers, occupied most of their non-work time and as such were the “free time” imposed on workers by the bourgeoisie. Non-work time could not be allowed to become time for the development of workers’ self-conscious.

Ljubodrag Simonovic: The Last Revolution

Contents

- Life-creating mind against destructive mindlessness

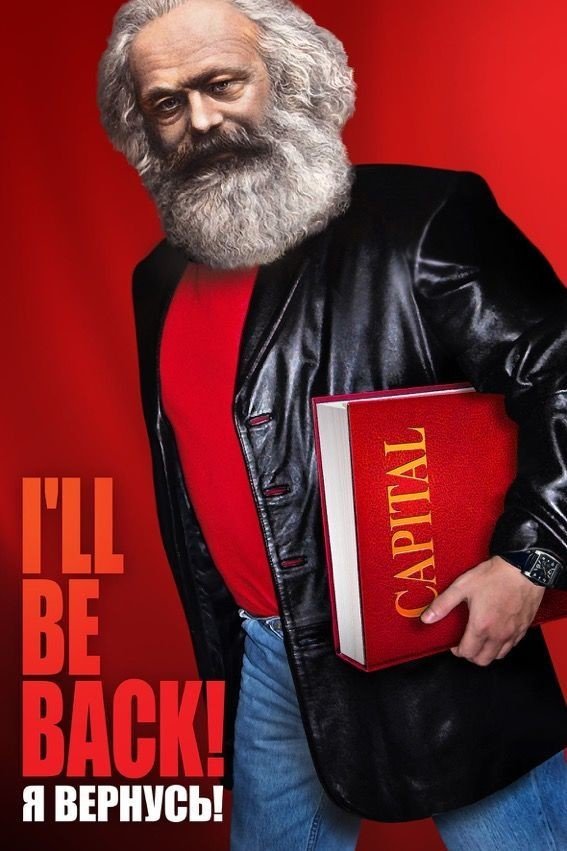

- The nature of Marx’s critique of capitalism

- Marx’s conception of nature

- Capitalist exploitation of soil

- “Humanism-Naturalism”

- Marx and capitalist globalism

- The cosmic dimension of man

- “Alienation” and destruction

- Destruction of the body

- Homosexuality

- Capitalist nihilism

- Productive forces

- Dialectics and history

- The integration of people into capitalism

- Technique as myth: Zeitgeist fascism (Part 15a) •|• Technique as myth: Zeitgeist fascism (Part 15b)

- Contemporary bourgeois thought

- Politics as a fraud

- Contemporary critique of capitalism

- Bourgeoisie and proletariat

- October revolution

- Contemporary socialist revolution

- Revolutionary violence

- Vision of a future

- Notes

The Last Revolution -- Chapter Twenty Three

Vision of a future – Radical reduction in labor time

(Translated from Serbian by Vesna Todorović/Petrović)

- Direct democracy;

- Production for meeting genuine human needs;

- A radical reduction in labor time;

- The development of man’s creative being;

- The development of interpersonal relations;

- The establishment of a humanized relation to nature.

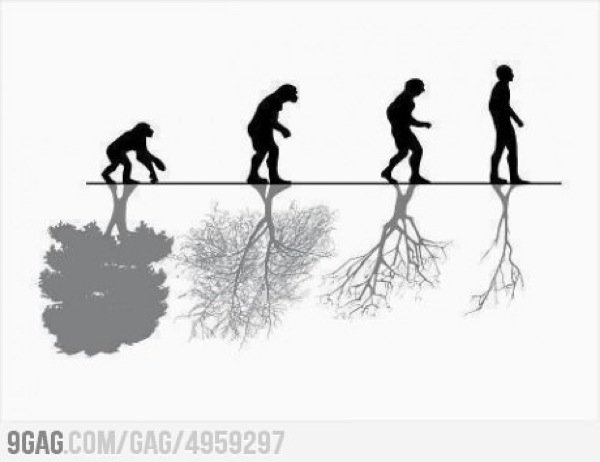

For Marx, labor is the “exchange of material and intellectual goods between nature and man” and as such is a way by which nature and man are humanized. It is the creator of all social wealth; the means for transforming nature into useful objects; the means by which natural forces are mastered and used to liberate man from his dependency on natural elements; the basic existential and essential way by which sociability is created; the way through which man realizes his creative potential and creates his own world; the basic way by which man reproduces himself as an authentic and independent being; the way in which the emancipatory potential of matter and living nature is reached; the basic opportunity for a “leap from the realm of necessity to the realm of freedom” (Engels) and the creation of a humane (communist) society… As such, labor is “life’s prime want“ (Marx) and the activity that enables man to optimize the chances of humanity’s survival.

One of the most important characteristics of capitalist labor is that it creates a time off from work or a potentially free-time, when workers can improve their education, organize themselves to fight for their labor, civil or human rights. Marcuse cites Marx’s view of how free time affects man: “Free time transforms its possessor into a different subject, and, as a different subject, he enters the process of immediate production.“ [32] Here it should be added: as a potentially different subject – provided that it is really about free time and not just some putative “free time” that is used to reproduce the ruling relations and values, as is the case with the leading forms of play. Leisure time is not an abstract, but has a concrete historical nature: though non-working time is “free” from work, it is not free from capitalism nor from the consequences for the worker: mutilation of his erotic being, physical and mental degradation of man and his interpersonal relations… Marcuse creates the psychological profile of a future man in relation to the man-laborer, who creates use-values, and not in relation to the man-destructor, who has become part of a destructive working-consuming machine. By becoming a homo faber, man has suppressed and lost his authentic human qualities (erotic nature), which reached its peak in capitalist society, as a “technical civilization”, where man was both dehumanized and denaturalized. Marcuse fails to realize that technical progress in capitalism is not only an “instrument of domination and exploitation“, but a weapon for obliterating the living world, climate, man as a biological and human being, interpersonal relations… In addition, technical progress has created such devastating industrial plants (above all, nuclear power plants) and military facilities that can annihilate humanity in a matter of seconds.

In “consumer society”, work and non-work time have become the constituent parts of capitalist time: time for production and time for consumption. Also, the content of non-work time is conditioned by class relations, by seeking to use non-work time in the defense of the ruling order. The bourgeoisie tries to prevent non-work time from becoming free time for the oppressed. Stadiums, designed according to the Roman Colosseum, were built at the end of the 19th century, when workers had won the right to an eight-hour work-day, in order to keep the “working masses” under control during non-work hours. The predominant forms of play, which were to become the cheapest principal spiritual food for workers, occupied most of their non-work time and as such were the “free time” imposed on workers by the bourgeoisie. Non-work time could not be allowed to become time for the development of workers’ self-conscious. It was, instead, to be the means by which they are drawn into the intellectual orbit of the bourgeoisie for the purposes of capital reproduction, which means it is consumer time. This is particularly important today when, due to the imposed dynamics of innovation necessary to survive in the market, instead of plants and equipment, man has become the most important “capital investment”. The force that now drives capitalism is the creative mind, suggesting the objective possibilities for a libertarian totalization of the world by a (liberated) mankind are created.

|  |

|---|

Apart from capitalist labor based on the principle of profit, history has known other, substantially different, images of labor. Labor has been seen as a means for the satisfaction of human needs, a realization of man’s erotic nature toward the attainment of a “higher purpose”. For Luther, labor is a “service to God”. Fourier insists on an anthropological starting point. The nature of labor is determined by man’s erotic nature: labor becomes a “festivity”. In Fromm, labor has a personal character and an artistic dimension. In Anti-Dühring, Engels writes about the “productive labor that, instead of being a means of subordination, becomes the means for human liberation, offering to each individual a chance to improve his faculties, both physical and mental, and apply them in all spheres, thus turning labor into a gratification instead of a burden”.[33] Marx criticizes externally imposed labor, where man is a hired hand, and advocates for the labor of free people as being “life’s prime want”. Writing on the subject of labor in a socialist society, Marx concludes: “Freedom in this field can only consist in socialized men, the associated producers, rationally regulating their interchange with Nature, bringing it under their common control, instead of being ruled by it as by the blind forces of Nature; and achieving this with the least expenditure of energy and under conditions most favorable to, and worthy of, their human nature. But it, nonetheless, still remains a realm of necessity. Beyond it begins that development of human energy which is an end in itself, the true realm of freedom, which, however, can blossom forth only with this realm of necessity as its basis. The shortening of the work-day is its basic prerequisite.“[34] These ideas are characteristically based on an abstract anthropological picture of man as a reasonable, artistic and libertarian being. In light of the increasingly dramatic global decline, the nature of labor in the future will be conditioned by the consequences of the destructive practices of capitalism. In order to become “life’s prime want”, labor must first become an existential imperative. By destroying natural living conditions, capitalism has forced humanity to deal with the issues that threaten its survival. In other words, in order for man to realize his potential as a universal creative being of freedom, labor must first heal the consequences of capitalist “progress”. The existential challenges posed by capitalism as a destructive totalitarian order will condition the character of labor in the future, the character of man’s relation to nature and the character of his overall living and social engagement.

The true ideal of labor (in the sense of both praxis and poiesis) cannot be reached from a fragmentized world, but only from the assumption of man as a totalizing creative being, because labor appears as one of the specific forms in which man’s universal creative being is manifest. The idea that play is possible only in relation to work assumes that the starting point is play and not man as a playing being and the agent of the totalization (humanization) of social life and nature, including labor as an interpersonal relation and man’s self-creating activity. Instead of alienated labor and play, man should be the starting point, as a universal creative being who relates to labor in the entirety of his totalizing libertarian and life-creating practice. Then, it will not be possible to apply the mechanistic scheme of the “reciprocating effect of play on labor“, with man being solely a mediator between social spheres alienated from him. The elimination of the duality of work and play requires that man no longer be consider in the dual role of homo faber and homo ludens but becomes an emancipated homo libertas.

As for the abolition of labor, in analyzing the processes of automation, Marcuse refers to Marx’s view of labor: “In the technique of pacification, aesthetic categories would enter to the degree that the productive machinery is constructed with a view toward the free play of faculties. But against all ‘technological Eros’ and similar misconceptions, ‘labor cannot become play…’ Marx’s statement rigidly precludes all romantic interpretation of the ‘abolition of labor’. The idea of such a millennium is as ideological in advanced industrial civilization as it was in the Middle Ages, and perhaps even more so. For man’s struggle with Nature is increasingly a struggle with his society, whose powers over the individual become more ‘rational’ and therefore more necessary than ever before. However, while the realm of necessity continues, its organization with a view to qualitatively different ends would change not only the mode, but also the extent of socially necessary production. And this change in turn would affect the human agents of production and their needs…”[35] Man’s struggle with nature is no longer a “struggle with his society”, but, above all, it is a struggle with capitalism, where the ruling ratio is but a manifestation of the destructive irrationalism of capitalism. Also, alienated (destructive) labor does not result in free time, but in non-work time, which becomes consumer time, when man destroys goods in order to open up space in the market. Capitalism turns work and non-work time into time for the reproduction of the dominant relations and values, which means that work and “free” time have become ways of a totalizing capitalistic temporalisation.

A radical shortening of working time is inevitable if work is no longer the means for capitalist reproduction, but the means for developing and meeting genuine human needs. The establishment of production for human needs eliminates the production of the unnecessary and the superfluous and introduces the production of the necessary, the main qualities of which are functionality and endurance. It enables a radical shortening of the time necessary to produce the goods and services needed for a normal life. Man, as an emancipated creative being, and society, as the community of free people, are the sources of genuine human needs.

Contemporary capitalism has “unified” the existential and the essential spheres: the fight for freedom becomes an existential necessity, and the struggle for survival becomes the basic libertarian challenge. The spheres of labor, art and play are no longer the starting points for libertarian practice. Instead, the starting point is man as a totalizing life-creating being, who perceives his entire life at the existential-essential level, that is, in the context of the fight against capitalism, which has transformed natural laws, social institutions and man into a vehicle for the destruction of life. In that context, labor, through which man’s life-creative powers are being realized and a genuine human world created, becomes an essential activity. As the present day production of commodities (goods) concomitantly brings on the destruction of life, in that very same way, in a future society, production of commodities will mean production of healthy living conditions and the creation of a healthy man. In the future, the basic task of humanity will be to re-establish environmental balance and, thus, create living conditions in which man can survive. The development of productive forces, labor processes, themselves, leisure time activities – practically all of life – will be subordinated to it. The fight for survival has at once become the contemporary “realm of necessity”, and man will come out of it as a totalized life-creating being.

The Last Revolution (Part 22) << Previous • Part 23 • Next >> 4#6 The development of man’s creative being