Today I will continue my series on the free will problem. I suggest you read the two previous articles on the matter before continuing:

Free-Will vs Determinism - Round 2

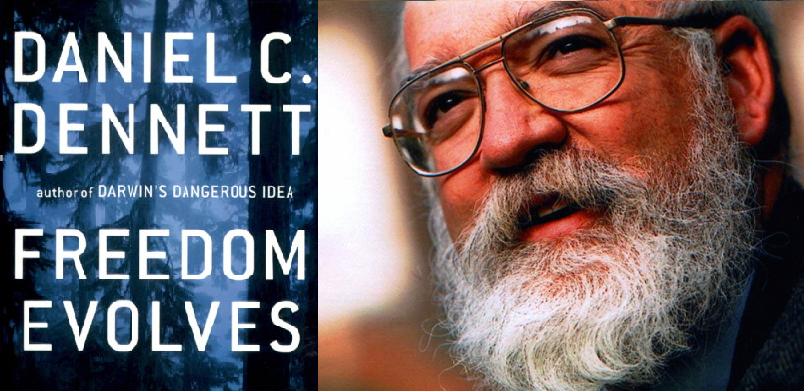

This time, the article will be based on a book that I've just finished; "Freedom Evolves" by Daniel Dennett. Enjoy!

The question whether or not we possess free will is one of the fundamental philosophical issues of our time. He who believes in freedom of the will live with responsibility as a guiding star and perhaps even with existentialist angst as travel companion. Anyone looking for the determining factors in genes and upbringing removes some of the responsibility and anxiety from the individual, and instead puts strong emphasis on the specific conditions and the context in which we live. The big debate has been centered on whether the will is free or not - but more rarely on the type of free or 'unfree' will.

Normally, the discussion emanates from the Newtonian universe where there is no moral responsibility, but only eternal cause and effect. No one creates something of their own free will and what looks like free choices are just 'cosmic coincidences' determined by the Aristotelian first cause, or the big bang. In such a world the moral responsibility is dissolved in the acid of causality. There can be no moral responsibility in a world where the universe is nothing more than a 'soulless' clockwork ticking on since the beginning of time. Laplace's Demon can sit quietly and figure out the world on the basis of the positions and movements of the particles. In such a world there is no free will, and many of us therefore strongly oppose this worldview and define it as deeply 'inhuman', perhaps even depressing.

Instead suppose the opposite: an indeterministic universe (read the previous blog on free will to understand indeterminism) where no condition is a result from a previous condition, and thus where no causality exists. If we take away the mechanical causality, we're not really making room for free will at all, because in a completely indeterministic universe, or society, there is no room for moral responsibility either: everything happens by chance! The question then becomes, confusingly enough: what kind of free will would you choose if you had any?

The philosopher Daniel Dennett has devoted two books on this subject, "Elbow Room: The Varieties of Free Will Worth Wanting" (1984), and "Freedom Evolves" (2003), where he brings up the question of what kind of free will really is worth having. And if there is such a thing as free will at all.

In order not to allow any gaps in the arguments, Dennett constructs an imaginary interlocutor, Conrad, who is always questioning the ideas of Dennett to really assure the reader that the issue is adequately covered. Simply put, the thesis of Dennett in the book is that the idea of free will is false, but that responsibility doesn't require free will in order to exist. At the same time it's clear that Conrad's role is to convince the reader of Dennett's view, to get the reader to choose to believe Dennett. Conrad is an expression of the reader having a choice, a free choice, and it shows how deeply rooted the belief in free will is in our imagination.

Although I believe that Dennett is right - the contradiction between free will and morality can be a chimera (see Augustine's discussion on sin) - the notion of free will is rooted in and an indispensable part of our thinking and language. In a way, free will resembles a Kantian category - we can't see the world other than through the lens of free will.

How is Dennett then attempting to solve the issue of free will? His solution consists in part of pointing out that we are describing the world at various levels - the physical, the mechanical and the intentional. The division of the world into different levels of description is a philosophical method that Dennett also uses in earlier works, and it is a really useful tool to analyze questions about the nature of consciousness. Dennett has argued that the question of what is conscious is a matter of what we describe as conscious. If it is easier and more 'economical' to describe a system that conscious, on the intentional level, the system is conscious.

This philosophical methodology is well suited for a cognitive scientific analysis, even if there are objections against it (as it's unclear for whom it will be easier and more 'economical' - a lot of people say about their computers that "it doesn't want" and are using concepts that belong to Dennett's level of consciousness, while the majority of computer users would deny that a computer is conscious), but it's much more difficult to apply to the question of free will.

Dennett argues that it's a conceptual illusion that our actions inevitability would follow from physical determinism. The physical determinism and inevitability of our actions is precisely such phenomenon on two different levels: the physical level and something that Dennett calls the design level. He uses John Conway's "Game of Life" as an example - a kind of computer game based on simple, deterministic rules, is forming a variety of patterns. Some of the patterns behave like organisms, and it's possible to describe them as conscious, choosing and free - while they at the same time are determined, under the surface. The world could be deterministic at the atomic level without our actions having to be inevitable and predetermined, Dennett claims.

But how? Dennett's example might of course be highly unsatisfactory to some. The free will that remains in Dennett's world and in Conway's game is just a description, not an ontological fact. Is that a freedom that is worth having? Dennett counters the issue with a legitimate question: how would a more extensive free will that we claim to possess function? He believes that most theories of freedom of the will are based on weird ad hoc hypotheses (like the idea that it's quantum indeterminants on the particle level that generates free will) or religious dualisms of Descartes (the soul makes the decisions and the body executes them).

Both versions of free will fade under the blasting analysis of Dennett. It's in moments like these that Dennett is the most enjoyable. His critical faculties are dazzling, even when his arguments doesn't reach all the way. But, as he points out, the burden of proof is actually not on him, but on those philosophers who claim that there IS such a thing as free will.

Dennett is then giving a credible evolutionary explanation for the emergence of the concept of free will in which he argues that cooperation, morality and responsibility are necessary and powerful components in the evolutionary perspective in terms of survival.

Evolution promotes those living with a notion of free will, because they also cultivate responsibility and morality, he seems to say, and thus perhaps to some it seems that the portrayal of the free will that Dennett offers become even more unsatisfactory. Isn't free will more than an 'evolutionary trick' that our genes used for us to stop killing each other? Is morality just a competitive factor in the struggle for survival? Dennett's explanation is very well-argued and interesting - and far from easy to refute.

With this connection to evolution "Freedom Evolves" ties together with "Darwin's Dangerous Idea", and the philosophical method that Dennett himself calls naturalism, a willingness to use science as the basis of his philosophical work. As a reader though, I must admit that I sometimes felt a bit lost in passages of biological or genetic arguments.

The question of free will is certainly not solved with Dennett's book, but rather more insoluble than ever. Dennett demonstration of how hard it is to understand a world in which the will would be truly free, just adds insult to injury. Dennett himself, however, is much more optimistic. He believes that we need to change and reform our legal system and society at large to express our new insights into the evolutionary significance for our agency. Reforms such as castration of pedophiles could take into account the genetic determination of human nature, and the whole legal system could be built on evolutionary basis.

This, Dennett suggests, would be a truly interesting project. How would our legal system look like if it took evolution into account? What changes would we be able to implement, and how would we know if they were really true? Perhaps we should even be able to punish in advance, taking into account the likelihood that someone will commit a crime, given the background, genetics and other factors. The similarities with Philip K. Dick's "Minority Report" are striking.

Ultimately, however, the issue of free will remains as obscure and enigmatic as ever, Dennett's interesting and exciting efforts notwithstanding. The value of Dennett's book doesn't lie in the solutions, but rather in the new questions.