Greetings Steemit!

By now, you may be used to my blogs on lifestyle, travel, food and life, however, I have also written and contributed several articles on the dichotomies between Chinese and Western Culture, a broad topic which I intend to keep writing about. Some of the most important lessons I had from studying my Bachelors and Masters Degree in the UK are the greater understanding of westernised society, culture and it's people. I value these perspectives very much because they are (sometimes) vastly different from the the perspectives I once held exclusively, back home in China.

Anglo-Sino Cultural Exchange

It's important to continue this Anglo-Sino cultural exchange and help lower cultural boundaries, be more informed of local traditions, and build more connections with people from different cultures. So, in addition to my bi-lingual contributions, I'm also starting a series called "Lost in Translation".

The majority of my posts are bi-lingual, English and Chinese. For a short to medium length post, I spend a lot of time thinking about the content, but moreover how to translate concepts from one language to another. More often than not, the translating takes longer than the initial write-up, even then, I always sense some of my intended meaning is lost somewhere in the translation.

I realised long ago, that it wasn't the words themselves that lacked translation, but rather the situation offering no direct comparison. Today, the Chinese language remains one of the few syllabic languages in existence, with much of it's vocabulary deriving from ancient language and philosophy. For this reason, Chinese is often considered metaphoric, idiomatic and generally poetic. To understand it, you must grasp the context as well as the local customs associated with it.

Lost in Translation

Even the term "Lost in Translation" can be interpreted in various ways. Some use it referring to the loss of meaning or information when translated from one language to another. Whilst others use it to mean the loss of details when translating from one medium to another. How often have we expressed our disappointment in films adapted from books?

The movie, Lost in Translations was translated to 迷失东京 which when translated back to English, becomes Lost in Tokyo. This is often the case when translating text with deep contextual meaning and shouldn't be considered erroneous on the part of the translator. In the case of the movie, it was clearly irony used as a literary device, playing on the theme of the film.

Lost in Translation is also used when a description of an experience cannot convey a true understanding of the what the actual experience was really like. To this end, I would guess that most writers experience this fairly frequently.

Dictionary Definitions

A lot of Chinese words have dictionary translations but few mother tongue English speakers will truly understand what many of these words even mean. It would be unreasonable to expect a person unfamiliar with the foreign social concept, to understand the vocabulary associated with it. Especially when these concepts are completely void in their own upbringing and environment.

Filial Piety

Do you understand what this means?

For those that don't, (and I don't blame you), this is why I'm doing this series.

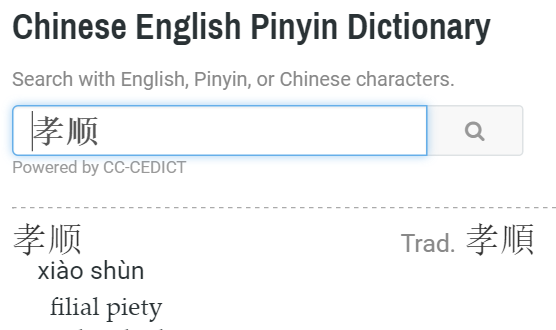

| Chinese | English | Pinyin |

|---|---|---|

| 孝顺 | Filial Piety | xiàoshùn |

Filial itself means "from son or daughter" and Piety means to carry duty and be devout. So, the general meaning is a devout and dutiful son or daughter.

The Chinese character 孝 is pronounced xiào. It's composed of two characters, the top character 耂 means old, and the bottom character 子 means child. You can see it as offspring supporting the old. From this logo-gram, we understand that this virtue manifested by xiao exists not only between parents and children but for any younger person towards an older person.

Thus, 孝 exists within the realms of a relationship and is influenced by the kinship of that relationship. This virtue has been taught to symbolise many attributes, most commonly - obedience, responsibility, duty, respect, provision and welfare, love, kindness, loyalty, tolerance, patience, politeness and so forth.

The character actually depicts the meaning very well.

The translation for filial piety should be considered a transliteration because of its limiting scope referring to the immediate child / parent relationship. In practical understanding, 孝 has flexibility and covers a spectrum of attributes which come in different qualities depending on the closeness of the relationship. Of course, the strongest form of 孝 is what Filial Piety (pertaining to Children/parents) attempts to describe but entails possibly more attributes pertaining to the 孝 of the individuals family and clan elders.

Family and Clans

If the family lives in harmony, all affairs will prosper |

Confucius philosophy believes not in the individual but the family unit. As such, the notion of 孝 is predicated on the importance of both the family unit and the family name / clan name. This means, you are insignificant without your family, and nothing without the family name which you carry.

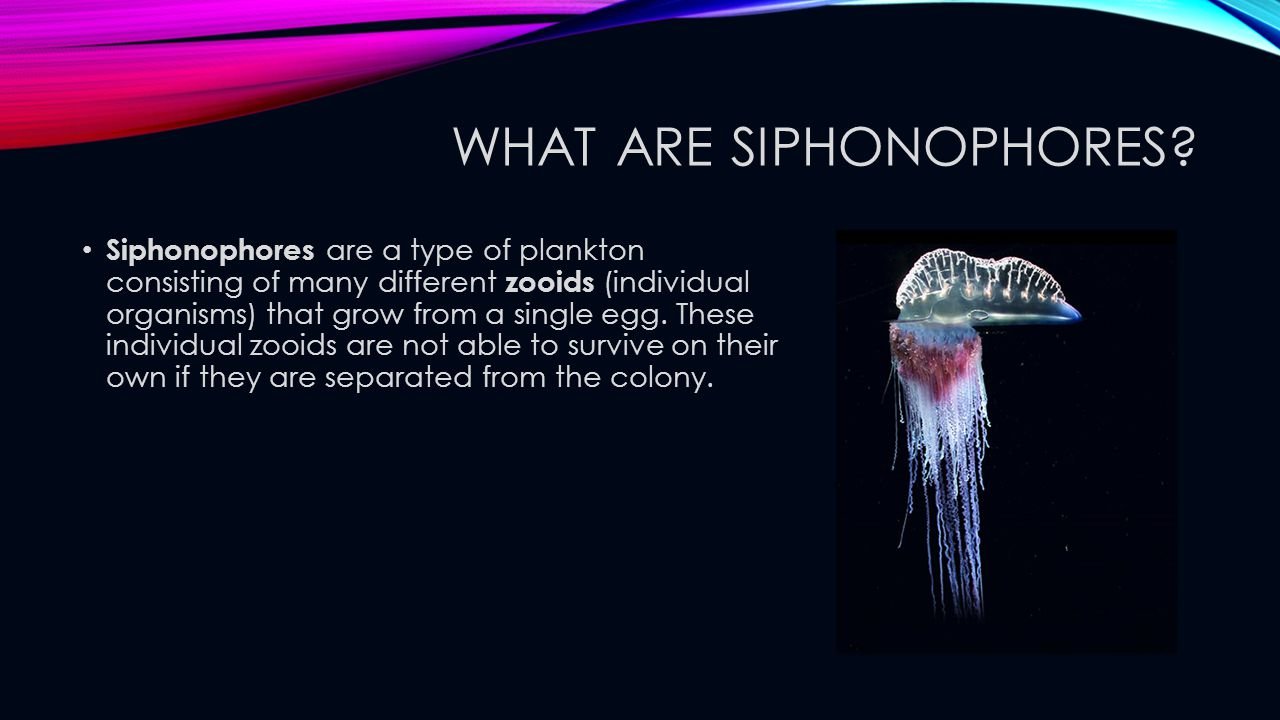

Think of Siphonophores |

This philosophy hence derives the importance of bringing honour to the family name, which is another face of the virtue of 孝.

To possess the virtue of 孝

To possess the virtue of 孝, is to be Chinese, to be Chinese is to have the prerequisite of the virtue of 孝. This philosophy is ingrained in the Chinese psyche and is an obligation for one who considers themselves Chinese. On the contrary, one who does not possess the virtue of 孝 is considered not Chinese (in the sense of a human) rather a foreign devil.

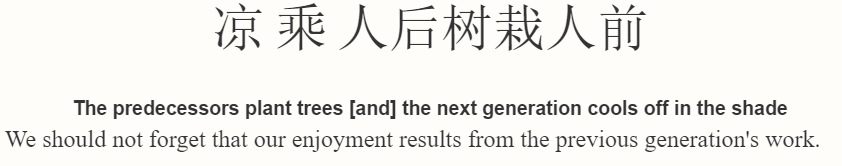

This essence of 孝 was founded in the Chinese tradition of ancestral Worship. We are not who, what and where we are today, if not for our ancestors carrying our family name. We, as a Chinese people would also not be where we are today if not for the continuity of our living heritage over the span of over 5000 years.

Thus, when Chinese people refer to themselves as humans, and others as foreign devils, it is in the sense of the Chinese being over 5000 years old, and others being young devils.

The virtue of 孝 remains a central ideology guarded by the Chinese for millennia, its moral conduct predates the philosophies of Tao, Buddhism and Confucianism despite being important in all three.

Are we lost yet?

As you can see, the meaning of Filial Piety carries with it, the weight of Chinese moral code nested unto the Chinese way of life. This detailed discussion of filial piety will help you understand the origins of its meaning, it's importance and place in Chinese society. Perhaps, it may enhance ones relationship with parents and supplement ones ideology of how to love ones parents.

In whichever case, the next time you see or hear about filial piety, there won't be any meaning lost in translation.

If you are interested in my other blogs related to Culture Exchange please check out these other blogs below

The Anti-social way of Socializing in Asia.

Why you don't see Chinese girls wearing Bikini's at the beach?

The Marriage Dilemma.

Having a Naked Marriage isn't a bad idea at all!

China's leftover women - Single and not necessarily successful!

It's Not Fair.

|