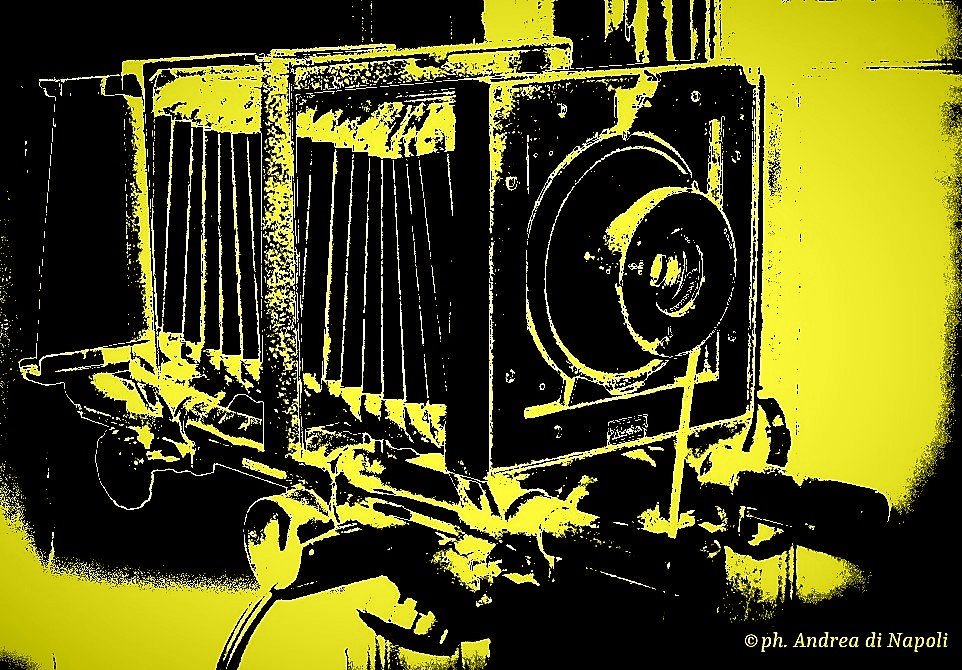

Lasciando passare la luce attraverso il minuscolo buco sulla parete di una camera oscura, gli Arabi erano in grado di tracciare un disegno fedele dell'immagine capovolta, che veniva proiettata sulla superficie opposta. Dopo avere applicato una lente in corrispondenza del foro, la camera ottica permise a pittori come Jan Vermeer di realizzare ritratti dalle espressioni spontanee, non più stereotipate, e di ritrarre i loro soggetti in pose abbastanza naturali che ricordano quelle delle moderne “istantanee”. Quando i supporti vennero resi sensibili, il foro stenopeico svolse la funzione di un rudimentale otturatore aperto che consentiva il passaggio della luce necessaria ad eseguire le prime fotografie.

In un campo in cui la precisione degli strumenti di ripresa ha quasi raggiunto la perfezione, la produzione fotografica, compiuta attraverso le tecniche iniziali dei pionieri assume oggi una valenza creativa. Non solo si può dimostrare la capacità di eseguire fotografie apprezzabili anche rinunciando alla consueta attrezzatura, ma la scelta di non utilizzare la tecnologia stimolerà la ricerca di immagini deliberatamente approssimative o, addirittura, piene di imperfezioni assolutamente volute.

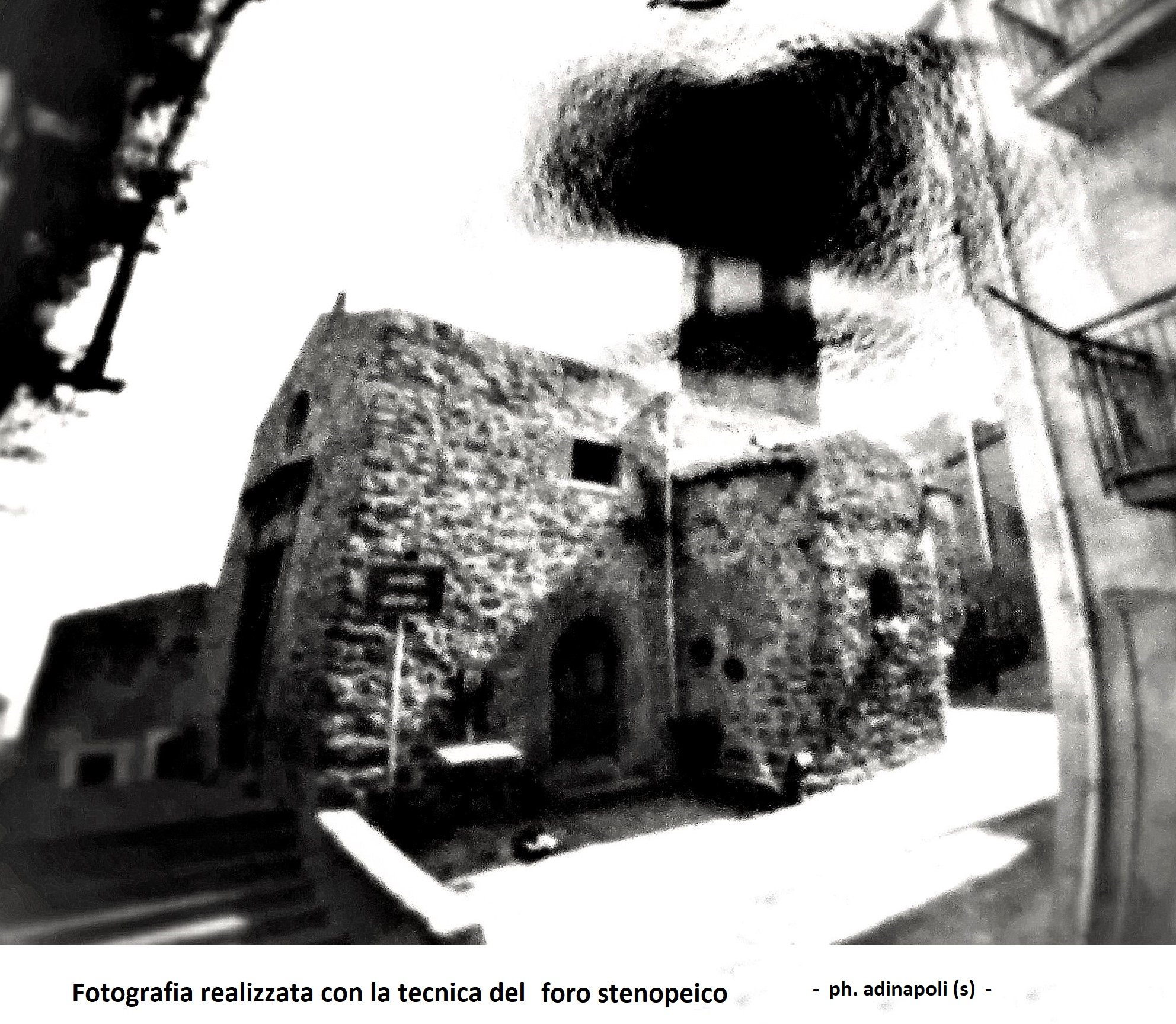

Diventano sempre più numerosi i fotografi che, ormai “annoiati” dalla eccessiva nitidezza delle immagini facilmente realizzabili, hanno trovato in una comune “scatola di cartone” e nella tecnica del pinhole un modo consapevole per rappresentare una realtà indistinta e vaga.

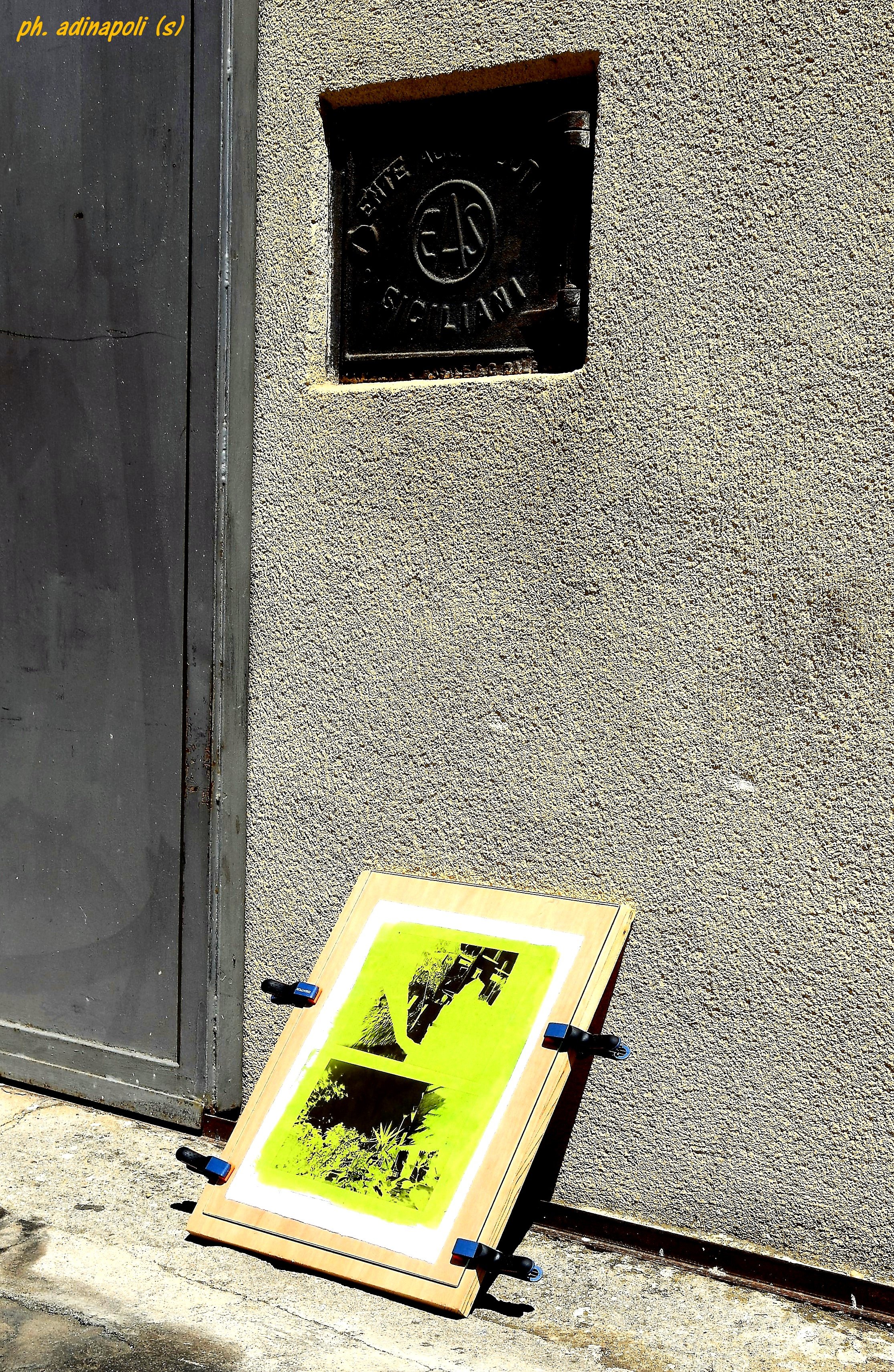

Le immagini ottenute con scatole stenopeiche, costruite con le proprie mani, possono essere anche stampate seguendo procedimenti ottocenteschi ad annerimento diretto, del tutto artigianali, come la carta salata, la cianografia o la gomma bicromata, su fogli di comune carta da disegno resi sensibili per l'occasione.

Una simile esperienza arricchisce evidentemente tutti gli appassionati delle tecniche del passato che partecipano con entusiasmo ai frequenti workshop organizzati da esperti emuli dei “proto-fotografi”.

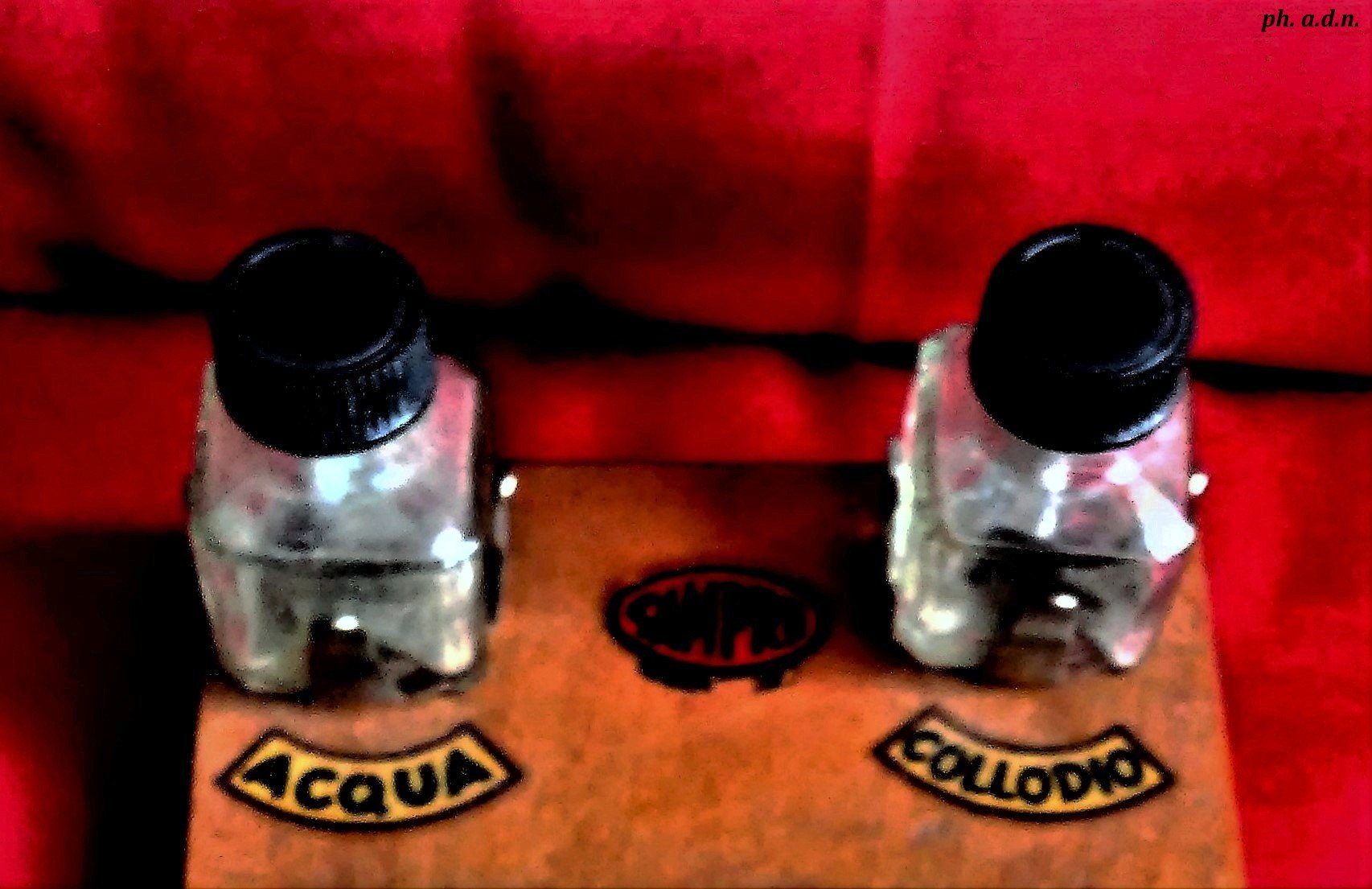

La funzione svolta fino al 1880 da una sostanza viscosa come il collodio, fu quella di legante tra i sali d'argento e il supporto rigido di una fragile lastra di vetro, per ottenere, attraverso un procedimento “non semplice”, gli ambrotipi, esemplari unici che venivano sottoesposti e montati su un “fondo” nero per apparire positivi.

Le lastre al collodio umido dovevano venire esposte prima che questo si seccasse e potevano anche essere trattate in modo da diventare negative stampabili su carta. Il collodio venne impiegato, inoltre, nella produzione dei ferrotipi, anche questi esemplari unici e positivi, su un sottile lamierino smaltato. Sfortunatamente i soggetti dovevano rimanere rigorosamente immobili per gli interminabili secondi di una lunga esposizione e il pesante supporto poteva facilmente andare in frantumi. Solitamente i fotografi inserivano gli esemplari unici in un astuccio protettivo. In seguito il collodio venne sostituito dalla gelatina di origine animale, più rapida e versatile.

La conoscenza e la pratica di antiche tecniche fotografiche consente di sfuggire alla spirale di prodotti sterili e omologati che, anche se perfetti, si differiscono poco l'uno dall'altro. Inoltre, come gli esemplari originali, la loro effettiva concretezza fornisce perfino il piacere del possesso tangibile di tutto quello che una fotografia rappresenta.

Testo e fotografie di adinapoli (s)

Le fotografie sono di proprietà dell'autore.

The hole, the glass and the photographs of the past

In about one hundred and eighty years since the official announcement of the invention of Photography, which dates back to 1839, dozens of shooting techniques have been adopted and different materials are used. By letting light pass through the tiny hole in the wall of a dark room, the Arabs were able to draw a faithful pattern of the inverted image, which was projected onto the opposite surface. After having applied a lens at the hole, the optic chamber allowed painters like Jan Vermeer to make portraits of spontaneous expressions, no longer stereotyped, and to portray their subjects in quite natural poses that recall those of modern "snapshots". When the supports were made sensitive, the pinhole performed the function of a rudimentary open shutter that allowed the passage of light necessary to make the first photographs. In a field where the precision of the instruments of recovery has almost reached perfection, photographic production, accomplished through the initial techniques of the pioneers, takes on today a creative value. Not only can you demonstrate the ability to perform appreciable photos even if you do not give up the usual equipment, but the choice not to use the technology will stimulate the search for images that are deliberately approximate or even full of absolutely desired imperfections. More and more photographers are becoming more and more "bored" by the excessive clarity of images that can be easily achieved. They have found in a common "cardboard box" and in the pinhole technique a conscious way to represent an indistinct and vague reality. The images obtained with pinhole boxes, built with their own hands, can also be printed following nineteenth-century procedures with direct blackening, entirely handcrafted, such as salt paper, blueprint or bichromate rubber, on sheets of common drawing paper made sensitive to opportunity. A similar experience clearly enriches all the enthusiasts of the techniques of the past who enthusiastically participate in the frequent workshops organized by expert emulators of "proto-photographers". The function carried out until 1880 by a viscous substance such as collodion, was that of binder between the silver salts and the rigid support of a fragile sheet of glass, to obtain, through a "not simple" procedure, the ambrotypes, exemplary unique that were underexposed and mounted on a black "bottom" to appear positive. The wet collodion plates had to be exposed before it dried out and could also be treated in such a way as to become negative printable on paper. The collodion was also used, in the production of ferrotypes, also these unique and positive specimens, on a thin enamelled sheet. Unfortunately the subjects had to remain strictly immobile for the endless seconds of long exposure and the heavy support could easily be shattered. Usually the photographers inserted the unique specimens in a protective case. Later the collodion was replaced by the jelly of animal origin, more rapid and versatile. The knowledge and the practice of ancient photographic techniques allows to escape the spiral of sterile and homologated products that, even if perfect, differ little from each other. other. Furthermore, like the original specimens, their actual concreteness provides even the pleasure of the tangible possession of all that a photograph represents.

Text and photographs of adinapoli