There are two beaches in the world that feature spherical rock concretions created by different layers of rock composed of varying densities of matter that eroded at different rates over time. One is north of me in Mendocino, California and the other is in New Zealand.

It was a stormy day when we left Mill Valley and I hoped that that weather would continue so that I could have a cloudy and stormy sky. It’s about a five-and-a-half-hour drive and when we got there at three o’clock, the tide was already at two to three feet and going out. I later discovered the optimal tides to shoot the rocks are between one foot and three and a half feet, so I got there right before the tide got so low that the base of the rocks started to get exposed, which is what you don’t want. You need a little water to be at the base so you’re not looking at rock on rock.

There are two beaches in the world that feature spherical rock concretions created by different layers of rock composed of varying densities of matter that eroded at different rates over time. One is north of me in Mendocino, California and the other is in New Zealand.

It was a stormy day when we left Mill Valley and I hoped that that weather would continue so that I could have a cloudy and stormy sky. It’s about a five-and-a-half-hour drive and when we got there at three o’clock, the tide was already at two to three feet and going out. I later discovered the optimal tides to shoot the rocks are between one foot and three and a half feet, so I got there right before the tide got so low that the base of the rocks started to get exposed, which is what you don’t want. You need a little water to be at the base so you’re not looking at rock on rock.

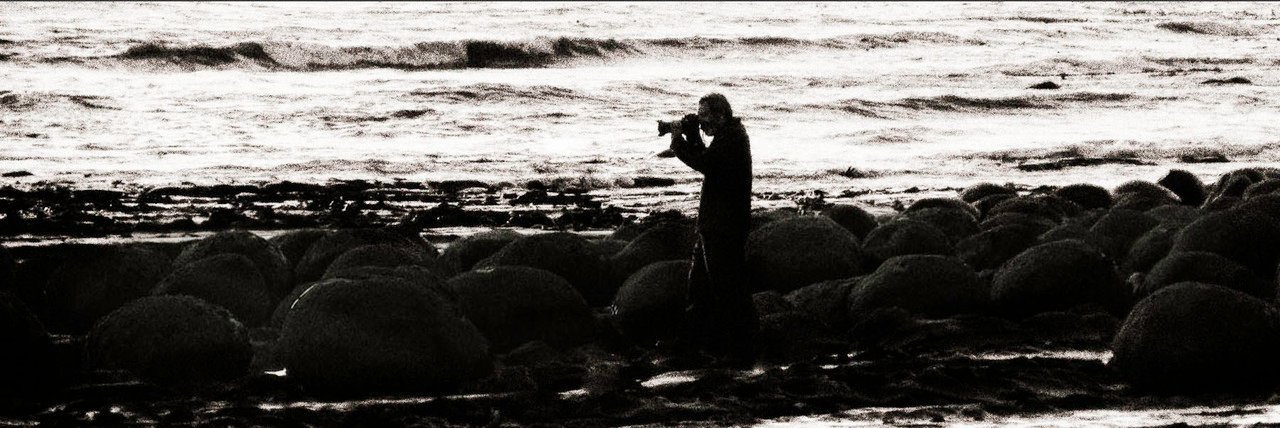

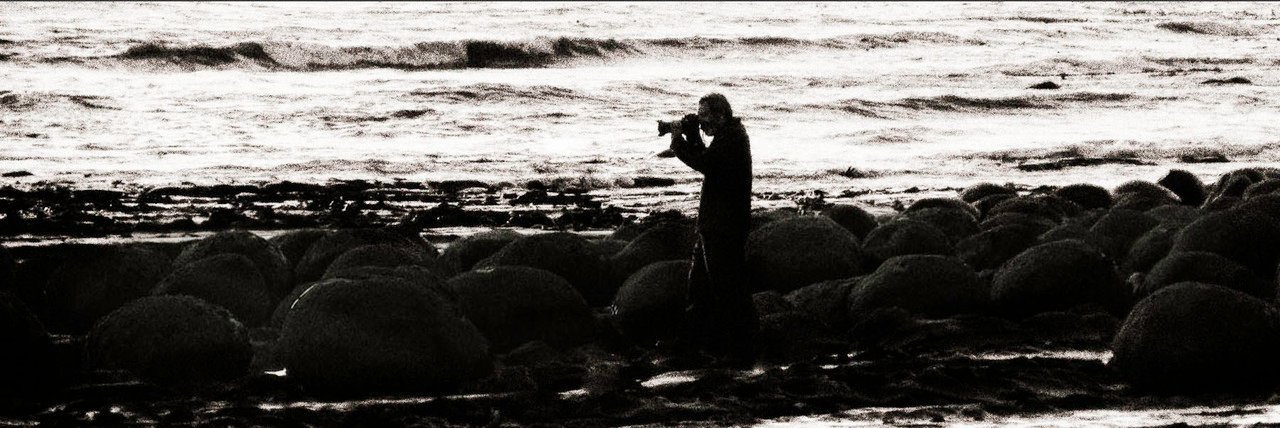

Here's the best shot I made on that first trip, but you can see that the tide was too low.

Getting confluence with the tide along with the late afternoon sun is a challenge. If you go to Bowling Ball Beach you'll optimally want a receding four-foot tide three hours before sunset. (Sunrise comes too fast and the light becomes over-bright too quickly.) Sunset allows for much longer shooting times during the alpenglow. These optimal conditions line up about once per month—tide and the light. And, if you’re lucky, the sky isn’t totally clear.

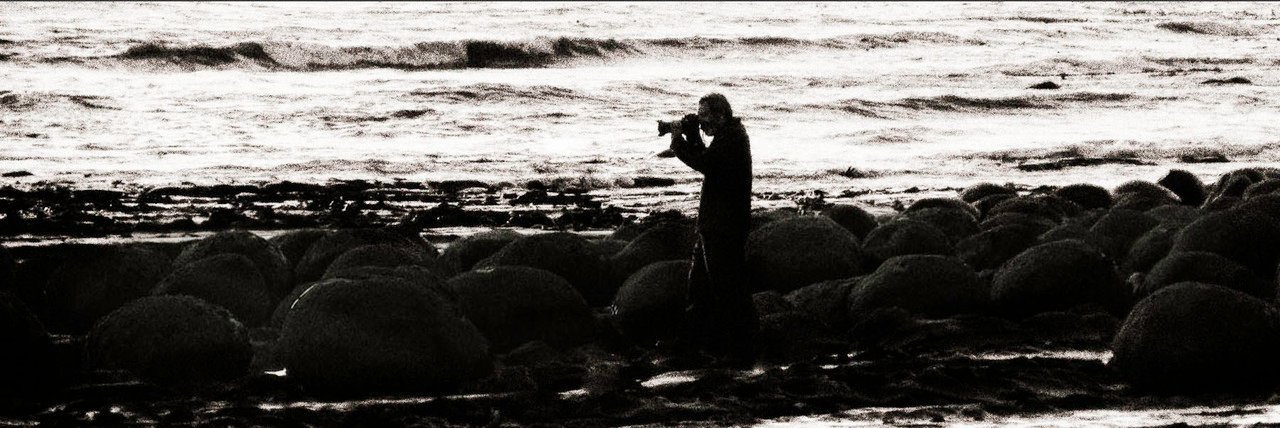

The stars aligned for me about 2 months later. I was prepared with big Wellington boots and waterproof pants that time, but on the day of the shoot I was coming down with the flu. I went for it anyway (obsessed). Got up there mid afternoon and the beach was totally empty, with no distractions.

I had taken a beater tripod that I could put in the salt water, two neutral density filters (eight and six stop), a Singh-Ray variable neutral density filter (goes from two to six stops), and a polarizing filter. When I first got there it was still fairly bright so it was obvious that if I wanted 30-second exposures, then I'd have to do something drastic, so I stacked all three of my neutral density filters together (20 stops) which (due to vignetting) limited the focal length of my 16-35 mm wide-angle zoom lens. I could only use focal ranges over 22 mm.

When you put 20 stops in front of your lens then the viewfinder goes completely black. I had limited time and had to work very quickly, so I would compose the image, turn off autofocus, screw the stack of filters on the lens—all while standing in freezing cold water. The experience was stressful because the surf was not calm and my gear isn't waterproof. I had to hold the tripod down so it wouldn’t float away while trying to keep it stable for 30 seconds.

The tide was great, the sky clouded over a bit and it was perfect. I was in the zone that day. Here's the fruit of that second trip, which shows that perseverance absolutely does further when doing landscape photography because it's critical to be there when all the right conditions of light and weather collide.

Here's an example of what it looked like at about a four-foot tide.

Getting confluence with the tide along with the late afternoon sun is a challenge. If you go to Bowling Ball Beach you'll optimally want a receding four-foot tide three hours before sunset. (Sunrise comes too fast and the light becomes over-bright too quickly.) Sunset allows for much longer shooting times during the alpenglow. These optimal conditions line up about once per month—tide and the light. And, if you’re lucky, the sky isn’t totally clear.

The stars aligned for me about 2 months later. I was prepared with big Wellington boots and waterproof pants that time, but on the day of the shoot I was coming down with the flu. I went for it anyway (obsessed). Got up there mid afternoon and the beach was totally empty, with no distractions.

I had taken a beater tripod that I could put in the salt water, two neutral density filters (eight and six stop), a Singh-Ray variable neutral density filter (goes from two to six stops), and a polarizing filter. When I first got there it was still fairly bright so it was obvious that if I wanted 30-second exposures, then I'd have to do something drastic, so I stacked all three of my neutral density filters together (20 stops) which (due to vignetting) limited the focal length of my 16-35 mm wide-angle zoom lens. I could only use focal ranges over 22 mm.

When you put 20 stops in front of your lens then the viewfinder goes completely black. I had limited time and had to work very quickly, so I would compose the image, turn off autofocus, screw the stack of filters on the lens—all while standing in freezing cold water. The experience was stressful because the surf was not calm and my gear isn't waterproof. I had to hold the tripod down so it wouldn’t float away while trying to keep it stable for 30 seconds.

The tide was great, the sky clouded over a bit and it was perfect. I was in the zone that day. Here's the fruit of that second trip, which shows that perseverance absolutely does further when doing landscape photography because it's critical to be there when all the right conditions of light and weather collide.

Here's an example of what it looked like at about a four-foot tide.

As the tide started to recede, I took the opportunity to work the scene more closely by making some tight crops of the barnacles on the concretions.

As the tide started to recede, I took the opportunity to work the scene more closely by making some tight crops of the barnacles on the concretions.

And then the sun started to set... the light became softer and the intensity of color increased.

And then the sun started to set... the light became softer and the intensity of color increased.

But there’s more to this story! An incredible bonus on that trip was bioluminescent plankton! I was wandering out on the bluffs that night and thought I was hallucinating because I was seeing green gas in the air. As my eyes adjusted to the light I saw that I was looking at huge clouds of green vapor. Every time the big waves hit the rocks the plankton would come off the rock in huge green clouds. It was obvious that I needed a long exposure at night, but anything more then 20 seconds you begin to get ellipsoidal star trails. At a relatively low ISO, I was able to capture the green in the water, which was like the color of glow sticks, but unfortunately that exposure was too long to see the spray of green foam in the air... it became a diffuse green glow. Luckily it was such a clear night that the Milky Way was perfectly exposed. This is a very very unusual shot and I went to sleep that night with the flu, but so so happy.

But there’s more to this story! An incredible bonus on that trip was bioluminescent plankton! I was wandering out on the bluffs that night and thought I was hallucinating because I was seeing green gas in the air. As my eyes adjusted to the light I saw that I was looking at huge clouds of green vapor. Every time the big waves hit the rocks the plankton would come off the rock in huge green clouds. It was obvious that I needed a long exposure at night, but anything more then 20 seconds you begin to get ellipsoidal star trails. At a relatively low ISO, I was able to capture the green in the water, which was like the color of glow sticks, but unfortunately that exposure was too long to see the spray of green foam in the air... it became a diffuse green glow. Luckily it was such a clear night that the Milky Way was perfectly exposed. This is a very very unusual shot and I went to sleep that night with the flu, but so so happy.

I hope that you've enjoyed these images. You can find my verification post here.

I hope that you've enjoyed these images. You can find my verification post here.