That's right, fellow poets, you read the title correctly ... a **_"Savagerean Sonnet._**

For those of who don't know, my surname is Savage and, to the best of my knowledge, I've invented it. Who cares? No one, including myself, rarely use this Verse Form. I find that the only ones who care about a poem being in sonnet form are other poets (even then, most of them don't care) and I target my poetry at the 99.99% of the population who prefer simpler Verse Forms.

The other day I was reading some of the posts in this Contest (I'm a judge in the Intermediate category), and I came across a poem by @ajremy, written as a sonnet. His explanation was that he was here to learn, to improve his craft, and hence his attempt (and a good one at that) to write a poem in one of the more challenging Verse Forms. @ajremy, I take off my hat.

That inspired me to do the same and provide an explanation about its composition.

What is a Sonnet?

Before going any further, a bit of history is in order. Sonnets have a long history in poetry, and they've been adapted from one language to another to exploit the nuances of each. Italian (rhyme-rich) is not the same as English (rhyme-poor) and a sonnet in the former sounds different than a sonnet in the latter.

Here is a nice summary of the two major sonnet forms in history:

Petrarchan Sonnet

The first and most common sonnet is the Petrarchan, or Italian. Named after one of its greatest practitioners, the Italian poet Petrarch, the Petrarchan sonnet is divided into two stanzas, the octave (the first eight lines) followed by the answering sestet (the final six lines). The tightly woven rhyme scheme, abba, abba, cdecde or cdcdcd, is suited for the rhyme-rich Italian language, though there are many fine examples in English.

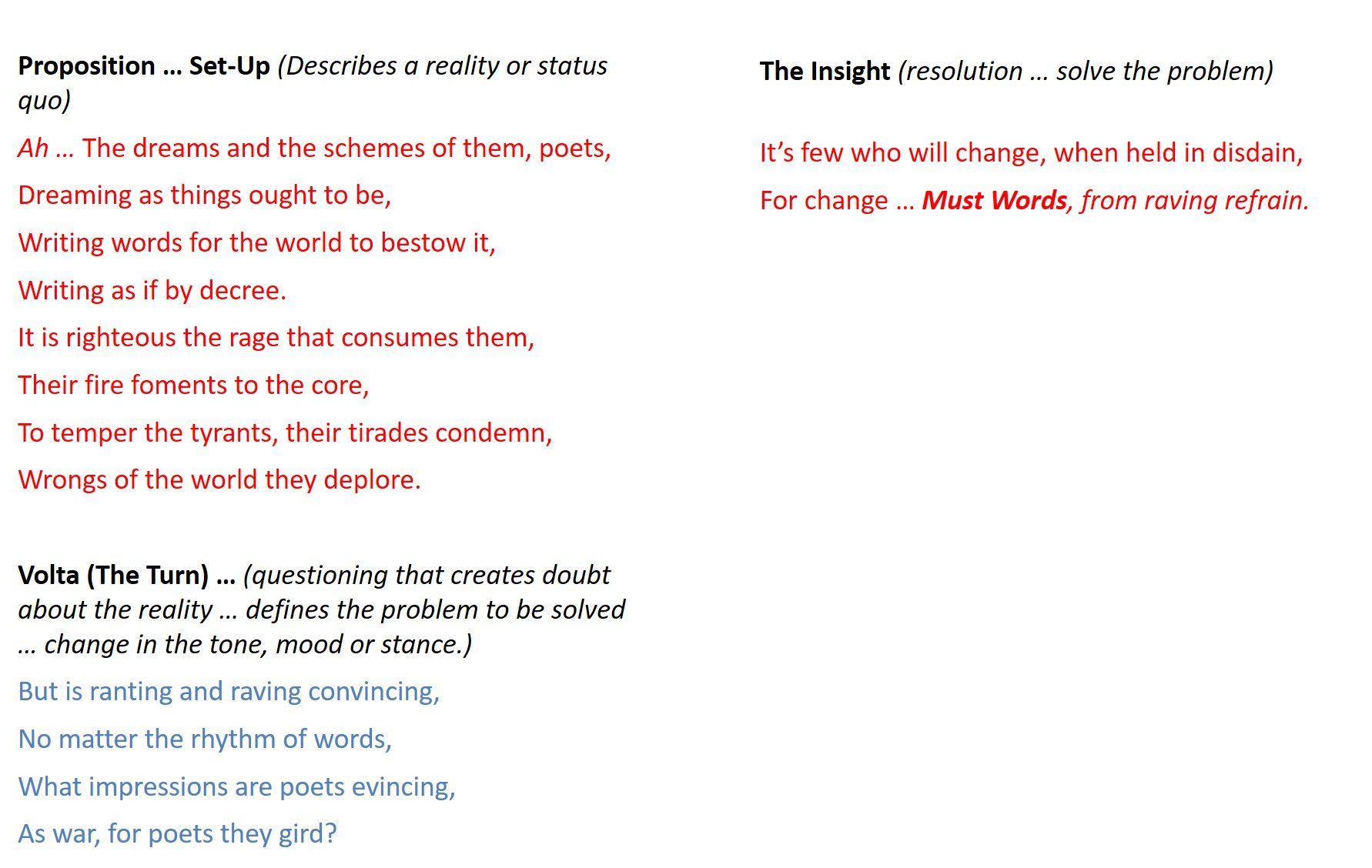

Since the Petrarchan presents an argument, observation, question, or some other answerable charge in the octave, a turn, or volta, occurs between the eighth and ninth lines. This turn marks a shift in the direction of the foregoing argument or narrative, turning the sestet into the vehicle for the counterargument, clarification, or whatever answer the octave demands.

And secondly, our beloved Shakespearean Sonnet:

Shakespearean Sonnet

The second major type of sonnet, the Shakespearean, or English sonnet, follows a different set of rules. Here, three quatrains and a couplet follow this rhyme scheme: abab, cdcd, efef, gg. The couplet plays a pivotal role, usually arriving in the form of a conclusion, amplification, or even refutation of the previous three stanzas, often creating an epiphanic quality to the end.

The Savagerean Sonnet

The Savagerean Sonnet has three characteristics:

- It utilizes the rhyme scheme of Shakespearean Sonnets to compensate for the rhyme-poor nature of English;

- It re-adopts the "Argument, Volta, Resolution" structure of the Petrarchan Sonnet; and

- It changes the meter of even-numbered lines from ten syllables to seven.

Rationale

The rationale for the first two characteristics are pretty straightforward. Choose a rhyme scheme that is more conducive to English and adopt an Argument Structure that is more conducive to Making An Argument.

Meter Modification

The third characteristic, meter modification, requires more explanation. As I've explained in other posts and comments, the Artistic Effects of poetry are determined by the Biological Processes that underlie them.

Our brains have something called, "Working Memory." Grossly over-simplifying, our Working Memories function like a water clock. Imagine a container attached to a hinge. Into it, you start pouring water. When it gets full, it tips over, dumping its contents. Now empty, it returns to it's starting position and the process starts all over again.

Our working memories can handle 5-9 chunks of information before they must dump (to be processed in other parts of the brain). Again, grossly over-simplifying, what this means in respect to poetry, is the that maximum "Neural Line" is 9 syllables long. That means that readers are "dumping" before the end of a 10-syllable line, dramatically interrupting the "flow." The complete line does NOT get dumped for further processing as a whole, but rather is broken up into bits.

Here's an experiment:

Remember the number sequence: 7-4-2. No problem, right? Why? Because you're well under your working memory's maximum limit of 9 chunks of information. So, you can just keep "refreshing" the sequence. 7-4-2 / 7-4-2 / 7-4-2. You get back to the beginning of the sequence before you're working memory has a chance to "dump" the information.

Now try this.

Remember the sequence: 6-8-9-2-1-7-6-4-8-3. That's 10 numbers. Much harder isn't it? The longer the sequence, the greater the difficulty. Why do you think phone numbers are seven digits long?

The reality is more complicated than explained. My area code is (941). As that number sequence has been committed to long-term memory, it can be recalled as a single chunk of information even though it's comprised of 3 digits. And so, adding it in front of a seven-digit phone number still only counts as 8 chunks of information total.

In sentences, the same thing can occur ... one chunk of information is not always equal to 1 syllable.

Nevertheless, pentameter (a 10 syllable line ... the traditional length of sonnet lines) forces a reader's working memory to operate at, or very near, 100% capacity all the time. That's why reading unfamiliar sonnets is so difficult. You're always stopping and going back and re-reading a line, breaking up the flow. Or, you have to read very slowly in the first place.

By switching to 10/7/10/7 ... your working memory gets to rest every second line.

If you go read my other poems, you'll notice that I typically write in quatrains with 8/6/8/8 meter (Ballad Meter) or 10/7/10/7 meter (Modified Ballad Meter, for lack of better terminology). But look carefully at the 10-syllable lines ... almost all contain a comma, semi-colon or "..." in the middle of the line.

This forces an "early dump." So, what you're actually reading is 5/5 ... 7 ... 5/5 ... 7. But, because the two 5-syllable sequences appear on the same line, you're unaware of my duplicity. :-)

There is Science Behind the Art whether we're aware of it or not.

Note that I marked deviations from the syllable count in blue. Whether you are dogmatic about the syllable count is up to you. No one notices the difference and, to me, the highest priority is ALWAYS writing a good-sounding poem that doesn't sound forced. Towards the end of his career (generally when he is considered to have written his best works), you'll find that Shakespeare became less dogmatic about syllable counts. And ... what's good enough for Shakespeare, is good enough for me. (Still, keep it close.)

Pattern

There are 4 types of pattern primarily used in Verse poetry: Meter; rhythm; rhyme and alliteration.

I explain this in much greater detail in other posts (go back and read through them if you're interested) but, in a nutshell, pattern causes the secretion of dopamine in our brains. Dopamine is responsible for creating focus, holding attention and the formation of long-term memory. It also creates, "Wanting."

If you read my prior poems, you'll notice that I frequently employ "internal rhyme" (rhymes within a single line) in addition to the typical tail-rhymes in lines two and four. I'm FLOODING your brain with dopamine.

In sonnets, however, the rhyme scheme is already pretty complicated and internal rhyme risks overwhelming a reader's ability to keep track of it all. And so, you'll notice how I lean heavily on alliteration instead. (I use internal rhyme in the first line as no rhyme scheme (pattern) has yet been established, and therefore nothing to confuse.)

And so, there it is. The Savagerean Sonnet and the logic of its construction. I hope you learned something of interest that, perhaps, you may be able to employ in your own poetic endeavors.

Let me know what you think in the Comments below.