Treaties.

We know they exist, but their impact is often elusive. A treaty, of course, is an agreement between nation states. They can involve everything from economic or trade matters (think NAFTA) to armed conflict (Geneva Convention) and peace (Versailles). More importantly, they can be used to promote basic human rights.

Shortly after its creation, the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which outlined the basic civil, economic, and cultural rights that should be afforded to every human being. Thereafter, separate treaties were created to address each of these rights. When a nation state (read: country) ratified ones of these treaties, they were agreeing to recognize and protect the rights on a domestic level.

Currently, there are eighteen international human rights treaties aimed at promoting and protecting the rights outlined in the Universal Declaration, only five of which have been ratified by the United States. While many consider this to be unacceptable, what they do not understand is that ratification is meaningless. The United States can enter into all eighteen, but it won't have an impact on a domestic level. Why? Because the United States attaches what is known as a "non-self executing declaration" to every treaty it ratifies.

Let's start with some background information.

Although treaties are governed largely by international law, a State’s process of becoming a party begins at the national level. Each States’ designated agent prescribed with the power to ratify international treaties is defined under the State’s domestic law. For the United States, Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution allocates the Nation’s treaty making power is to the President upon the “advice and consent” of two-thirds of the Senate present. While the power is conferred in only a single sentence, the process of treaty ratification in practice involves three essential stages.

First, an agent of the Executive negotiates the terms of the treaty and recommends the inclusion of any necessary reservations, declarations, and understandings. Second, the President submits the treaty to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee who, after holding a public hearing on the matter, provides a written report to be considered by the Senate. The Senate then conducts an "advice and consent" meeting as required by Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution. The treaty must receive the necessary two-thirds vote from those present in the Senate in order for the President to ratify it. If the requisite number of votes is not obtained from the Senate, the process is terminated and no further action may be taken on it.

While the United States’ ratification process may theoretically be boiled down to only three essential stages, the process in fact tends to be much more convoluted—i.e. politicized—depending on the nature of the treaty being recommended. This “politicization” was especially profound during the first proposal to ratify the international human rights treaties in the 1950s. Alongside the federal and state representatives, various political actors actively participated in the senate hearings, many arguing that the provisions touched on constitutionally settled matters and should therefore be relegated to the states. Without the protection afforded by the checks and balances of the normal legislative process, concerns were raised that a president's unfettered ratification of human rights treaties—with their broad protections and duties—ran afoul of the judicial precedent established by the Supreme Courts’ interpretations of the Constitution.

In an effort to compromise, President Jimmy Carter offered to attach what is known under international law as reservations, understandings, and declarations (RUDs) to the treaties which would, in effect, make so any rights not currently recognized by the United States weren't included (think dealth penalty). The Administration thought that most of the provisions were already consistent with established domestic law. The right to a fair trial or freedom of expression, for example, were earmarks of what it meant to be an American. Unfortunately, the debate led to a stalemate and, as a result, the United States failed to ratify most of the international human rights covenants until the early 1990s.

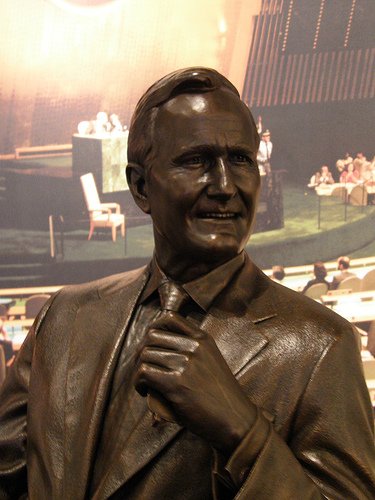

In 1991, the Bush Administration began encouraging the Committee to reconsider ratification with many of the earlier conditions proposed by Carter. Both Carter and Clinton's RUDs contained a declaration stating that the provisions of the treaty "are not self-executing.” After the requisite votes were obtained, the United States ratified its first international human rights treaty--the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights--on June 8, 1992.

Yes, you read that correctly. A BUSH was responsible for ratifying the first human rights treaty.

So what exactly is a non-self executing declaration?

The phrase “non-self executing” is not unique to just treaties that involve human rights. Instead, the origins of the phrase can be tracked back as far as 1829. It was in that year that the Supreme Court’s decision in Foster v. Neilson created the initial concept that treaties signed by the Executive did not automatically become binding law in the United States. The Court held that when a treaty's subject matter “[addressed] the political, not the judicial department . . . the legislature must execute the contract before it can become a rule for the Court.”

The specific reference to a treaty as “self-executing” or “non-self executing” came later in 1888, after the Supreme Court once again sought to discern whether a treaty that was ratified by the United States automatically became a part of the domestic law and was therefore binding on the judiciary. In Whitney v. Robertson, the Court held that a treaty whose provisions were deemed to be self-executing meant that the United States’ ratification of the treaty was akin to a legislative enactment —the provisions were considered binding law just like any other federal or state statute. If a treaty was considered to be non-self executing however, it meant that its provisions would not automatically be binding on the courts as is. Instead, a non-self executing treaty requires implementing legislation for the provisions to be considered “law." Absent such legislation, the judiciary is prevented from directly applying treaty provisions to reach a decision. The non-self executing treaty does not create private rights under law—like the First Amendment, for example—that can be vindicated in U.S. courts.

Has the United States ever enacted any implementing legislation?

No.